Blog by Deanna Vaughn, PT, DPT who practices at Core and Pelvic Physical Therapy Clinic in Conway, Arkansas, this article was originally located at https://whatsupdownthere.info/colorectal-cancer-the-gut-and-the-butt/.

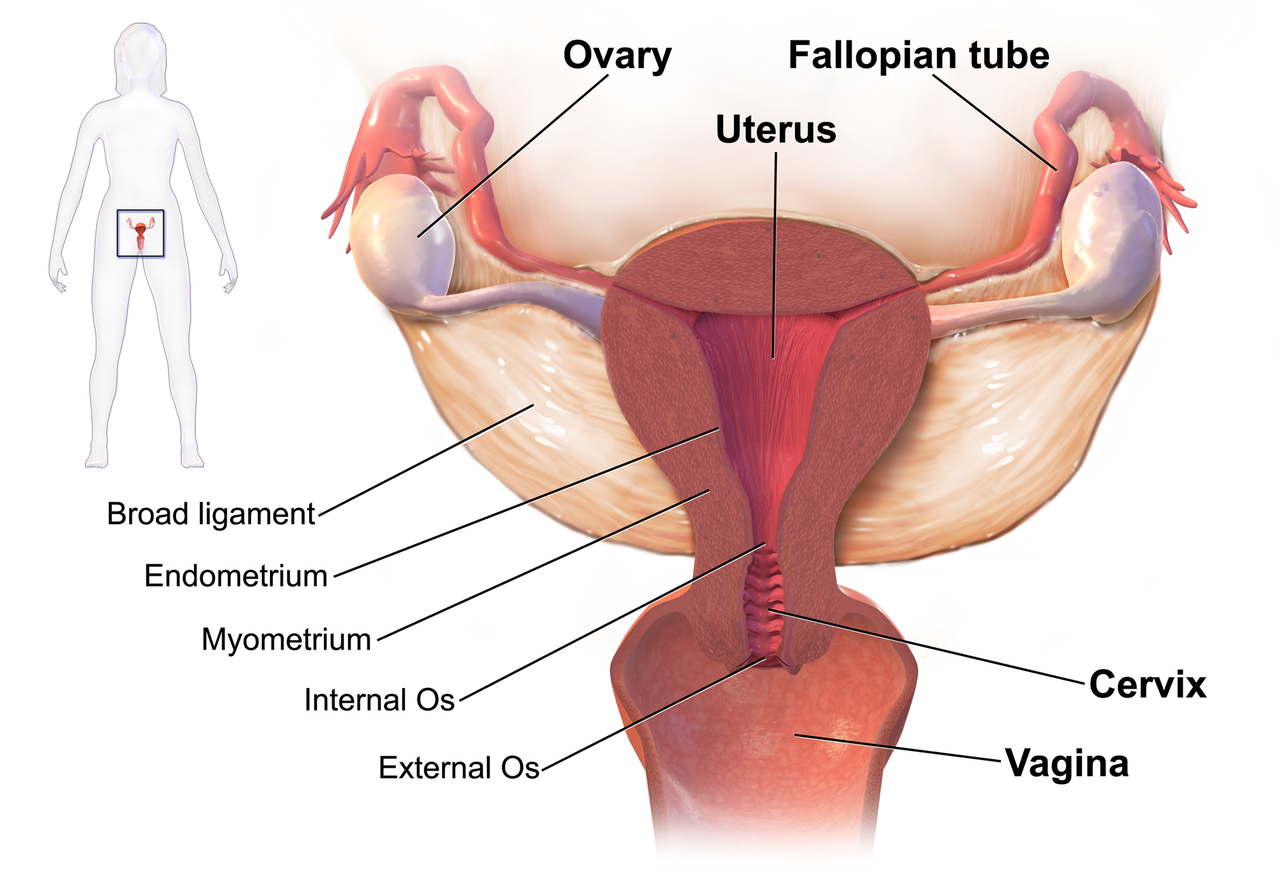

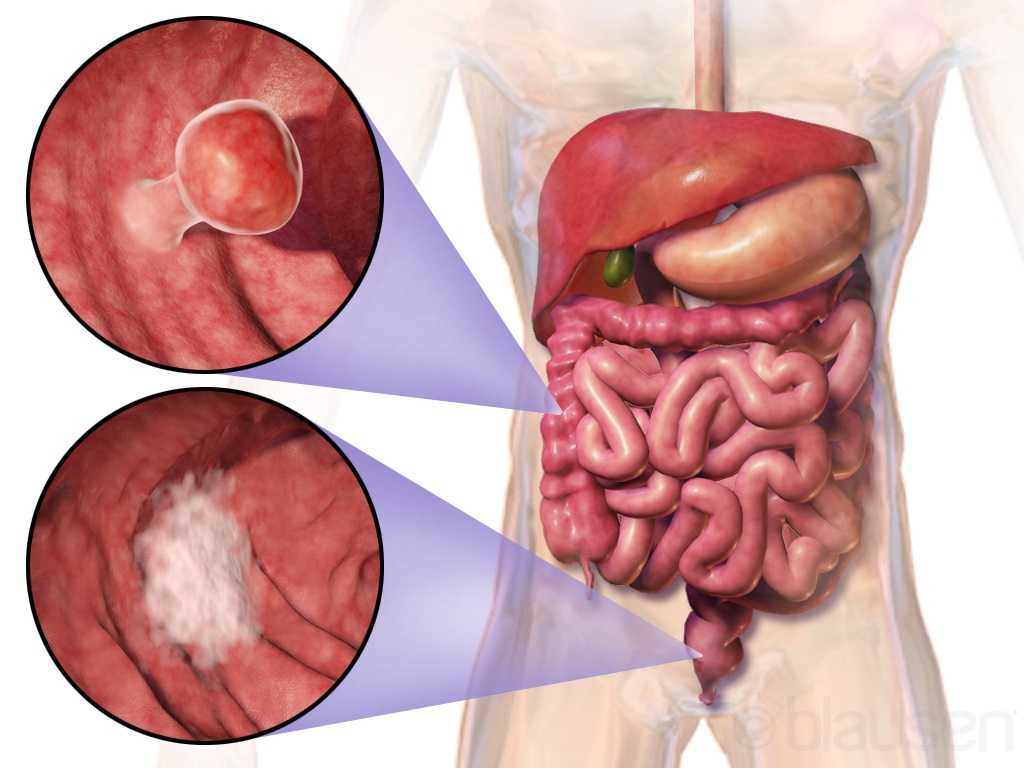

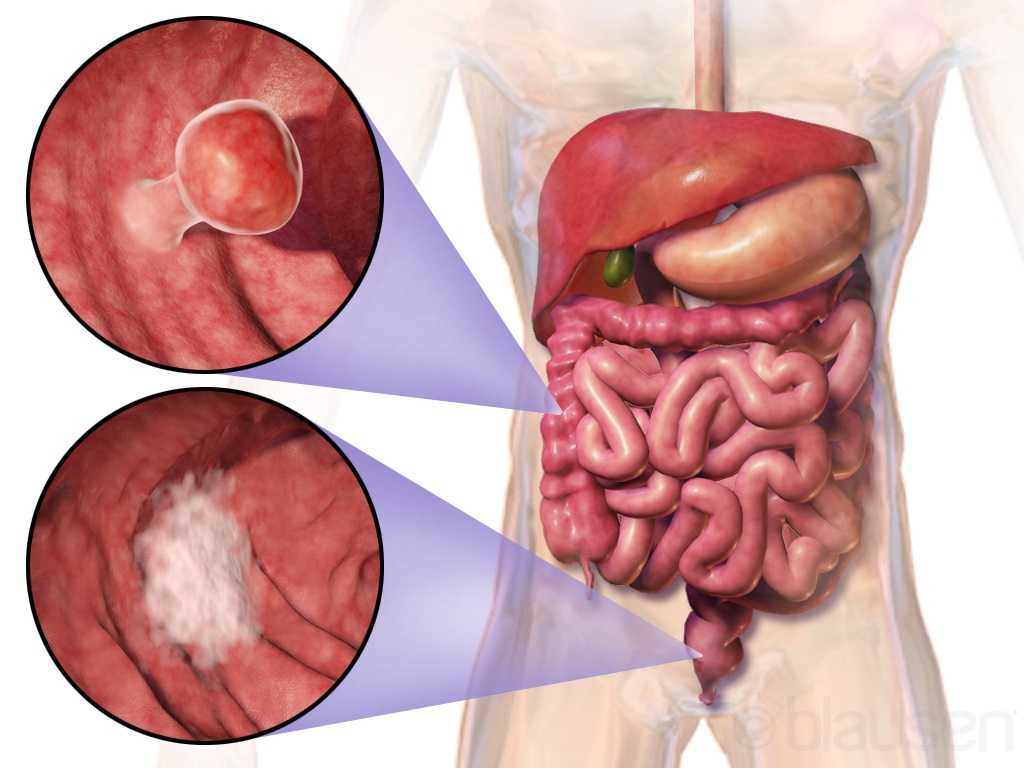

Colorectal cancer refers to cancerous cells within the colon or rectum. Need a quick anatomy review? Keep reading then!

The colon is another name for the large intestine, which is the long tube (nearly 5 FEET!) surrounding the small intestines (that snaky, jumbled tube in the middle of our bodies, which you can see below in the picture). It’s comprised of segments: the cecum (the little pouch that joins the small intestine to the large intestine) in the right lower abdomen, the ascending colon starting at the right lower part of your abdomen (coming off the cecum), and up to about the right side of your ribcage; the transverse colon that loops underneath the stomach and ribcage from right to left; the descending colon that extends down from the left side of your ribcage to the lower part of your left abdomen; and then the sigmoid colon that loops (in an s-shape) along the lower abdomen to the center of the body. At the end of the colon is the rectum, which pretty much connects the colon to the actual anus/anal opening for wastes to leave the body.

That being said, colorectal cancer can affect any part or segment of the colon and the rectum. If you have a family history of colorectal cancer, or if you have an inflammatory bowel disease (like Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis), then you may be at a higher risk for colorectal cancer. Other risk factors are the same for virtually any other health condition – genetics, no regular physical activity, poor diet, tobacco use, high alcohol consumption, etc.

So how would we know if it’s colorectal cancer – or precancerous cells, and how do we decrease our risk?

That’s where screening comes into play! Just like how someone may see their gynecologist annually and undergo the PAP smear every 1-3 years to check for any gynecological cancer (like cervical or labial cancer), someone may see their colorectal or gastrointestinal (GI) provider to check for colorectal cancer or disorders. Regular screening takes place around age 45 (although a person may be screened earlier if they are at higher risk or had a previous history of cancer).

What does screening look like?

There are a few tests that screen for colorectal cancer. These tests include stool tests, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy.

Stool tests – This pretty much involves you taking a sample of your stool via test kit provided to you, and returning it to your doctor/lab, where your stool is checked for any blood or other abnormal findings.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy – A thin, short tube with a light is inserted into the rectum. This allows your doctor to see any polyps or cancer within the rectum and lower part of the colon.

Colonoscopy – This is like the sigmoidoscopy, but with a longer tube. The longer tube allows your doctor to check for polyps/cancer inside the rectum and the entire length of the colon. Your doctor can also remove some polyps during this procedure if indicated.

Most people without any symptoms, abnormal findings or outstanding personal or family history of colorectal cancer will have these screening tests performed anywhere from 5-10 years.

What are the symptoms?

This is not an exhaustive list, but some symptoms may include:

- Bleeding, pain, and/or discomfort within the rectum/anus

- Blood in stool

- Abdominal pain and bloating

- Nausea/vomiting

- Difficulty or incomplete bowel evacuation

- Hemorrhoids

- Altered bowel habits (such as sudden constipation, diarrhea, change in stool consistency)

Now what are our treatment options?

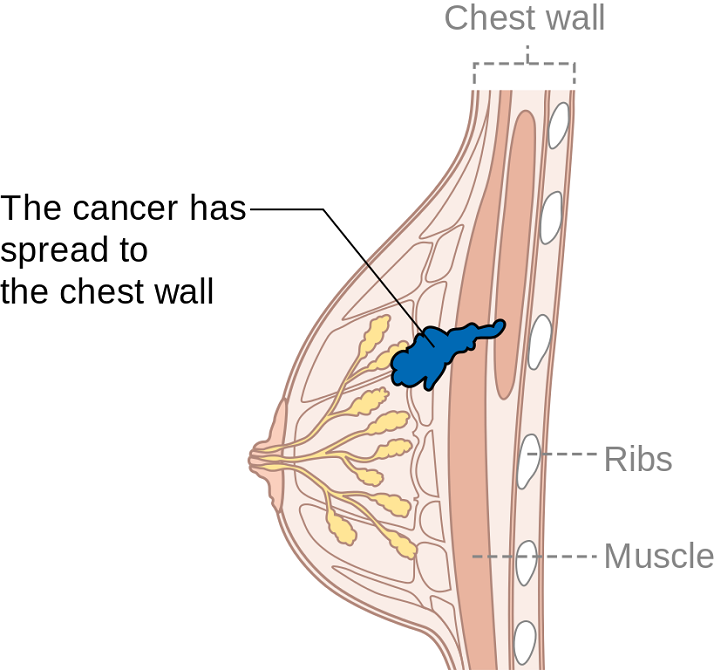

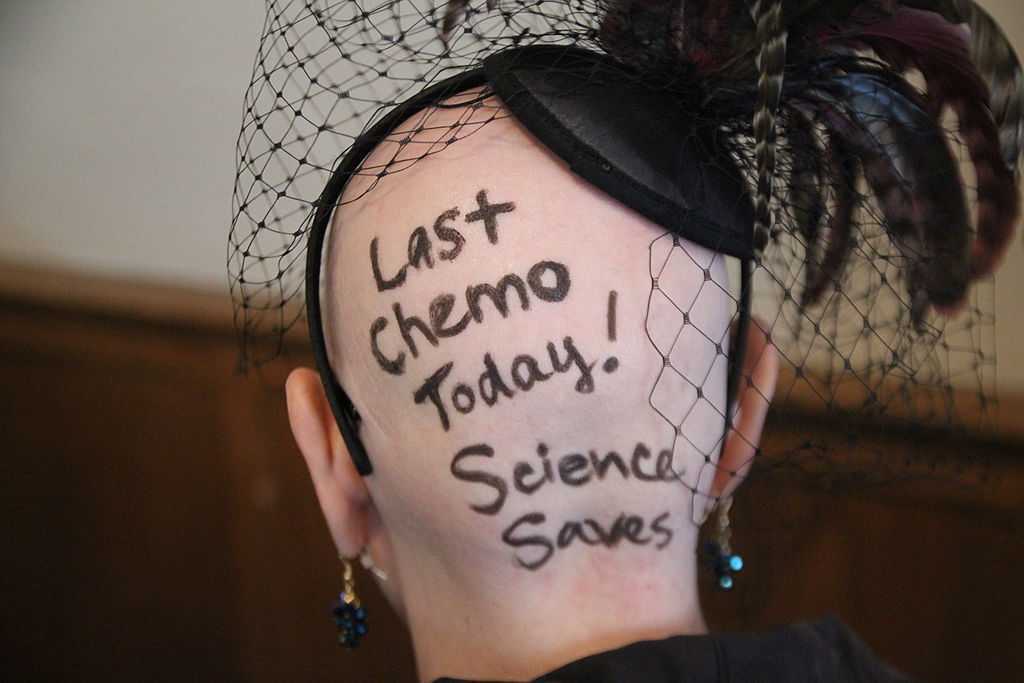

Besides preventative measures – such as getting regular physical activity, improving our diet, etc., treatment looks similar to any other cancer treatment. This may look like chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and/or surgery. Surgery may be indicated to remove polyps/tumors, or parts of the colon or rectum to eliminate cancerous growths. Thankfully though, regular screening of the colorectal region can find precancerous/cancerous cells early. Oftentimes, such as during a colonoscopy, your colorectal provider may go ahead and remove polyps that are abnormal or deemed precancerous at that time!

Now what about pelvic physical therapy? Can it possibly help?

Well, this is another condition (like Pelvic Congestion Syndrome in the previous blog post), where pelvic physical therapy is not the initial go-to or main treatment option. Individuals with colorectal cancer vary in several ways depending on staging/severity and overall health. Once again, pelvic therapy is a nice resource to utilize if you’re needing or wanting ways to manage your bowel symptoms.

Ways that pelvic PT CAN help may include: Teaching appropriate toileting – positioning to straighten out the anorectal angle and allow stool to pass more easily from the rectum; mechanics, such as exhaling smoothly when pushing for a bowel movement to prevent straining; Improving pelvic floor muscle function (strength, endurance, coordination) so that your body can delay defecation as needed and calm down bowel urges; and overall promoting health bowel habits by supporting your nutrition and keeping bowel movements regular.

Whether or not you (or someone you know) have colorectal cancer, developing healthy and safe bowel habits is key to a better quality of life. Working with your doctor and/or your team of providers is important in making sure your needs are addressed, but feel free to reach out to your local pelvic PT if you want more resources or guidance – even things like, “So, how SHOULD I be pooping??”

References & Resources

Brenner H, Chen C. The colorectal cancer epidemic: challenges and opportunities for primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. Br J Cancer. 2018;119(7):785-792. doi:10.1038/s41416-018-0264-x

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer.html

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14501-colorectal-colon-cancer

Kuipers EJ, Grady WM, Lieberman D, et al. Colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15065. Published 2015 Nov 5. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.65

Leslie A, Steele RJC. Management of colorectal cancerPostgraduate Medical Journal 2002;78:473-478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/pmj.78.922.473

Mármol I, Sánchez-de-Diego C, Pradilla Dieste A, Cerrada E, Rodriguez Yoldi MJ. Colorectal Carcinoma: A General Overview and Future Perspectives in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(1):197. Published 2017 Jan 19. doi:10.3390/ijms18010197

You YN, Lee LD, Deschner BW, Shibata D. Colorectal Cancer in the Adolescent and Young Adult Population. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(1):19-27. doi:10.1200/JOP.19.00153

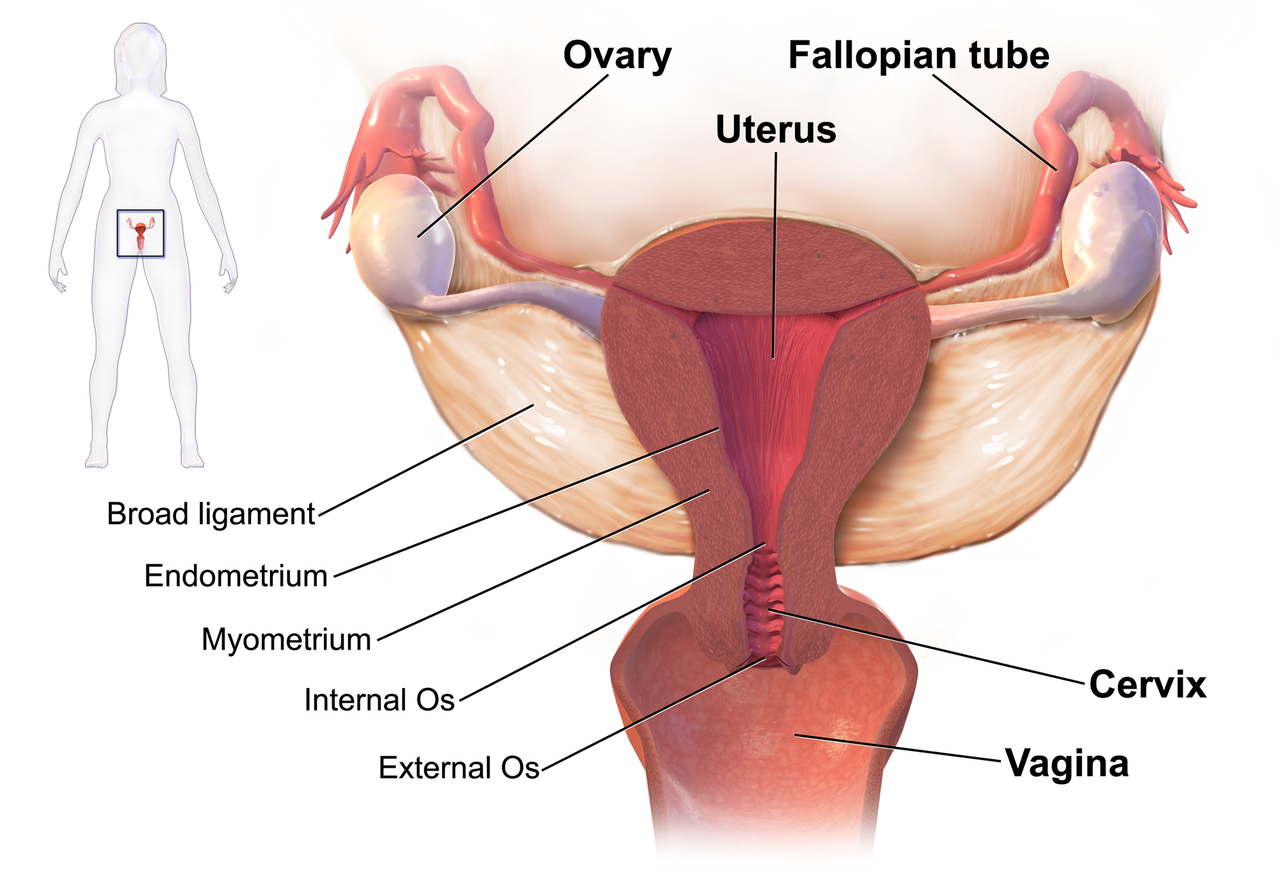

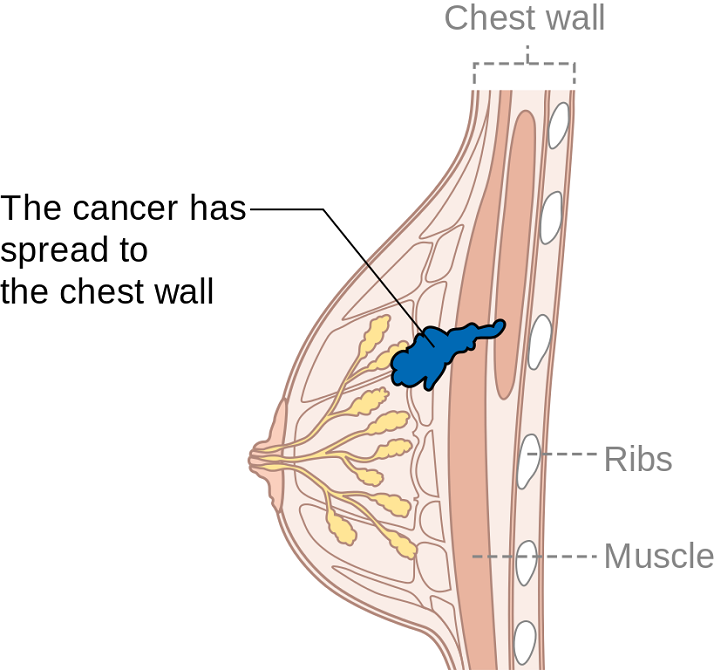

September is Gynae Cancer Awareness Month – but how aware are we as clinicians of the signs and symptoms, the epidemiology and the sequalae of treatment afterwards? As pelvic rehab specialists, we have the privilege of helping women live well after cancer treatment ends, both on a ‘local’ pelvic area (bladder, bowel, sexual and pelvic pain management strategies) but also on a more ‘global’ level – dealing with issues such as cancer related fatigue, bone health and cardiovascular concerns.

We know that women who are diagnosed with cancer of the vulva, vagina, cervix, endometrium or ovaries are treated with a combination of surgery, radiation or chemotherapy. However, with improving treatment and better survival rates, there is evidence that a variety of pelvic health concerns may arise for these women, both during and after treatment. (Hazewinkel et al 2010). For example, urinary incontinence is reported in 80% of women treated for endometrial cancer, with more severe symptoms and impact on quality of life in those who had adjuvant radiation (Erekson et al 2009) In Malone’s 2017 paper, ‘The patient’s voice: What are the views of women on living with pelvic floor problems following successful treatment for pelvic cancers?’, the author notes that ‘…there is currently a lack of knowledge regarding the effects of PFD on QoL in this cohort. Patients do not always report these problems to their health care providers and clinicians may underestimate symptoms…In the context of having survived cancer, PFD may be seen as relatively trivial. However, in the context of resuming normal living, the symptoms experienced by the survivors may be significant’.

We know that women who are diagnosed with cancer of the vulva, vagina, cervix, endometrium or ovaries are treated with a combination of surgery, radiation or chemotherapy. However, with improving treatment and better survival rates, there is evidence that a variety of pelvic health concerns may arise for these women, both during and after treatment. (Hazewinkel et al 2010). For example, urinary incontinence is reported in 80% of women treated for endometrial cancer, with more severe symptoms and impact on quality of life in those who had adjuvant radiation (Erekson et al 2009) In Malone’s 2017 paper, ‘The patient’s voice: What are the views of women on living with pelvic floor problems following successful treatment for pelvic cancers?’, the author notes that ‘…there is currently a lack of knowledge regarding the effects of PFD on QoL in this cohort. Patients do not always report these problems to their health care providers and clinicians may underestimate symptoms…In the context of having survived cancer, PFD may be seen as relatively trivial. However, in the context of resuming normal living, the symptoms experienced by the survivors may be significant’.

This can present a clinical conundrum – often pelvic rehab therapists are nervous when working with a patient who has a current or previous gynecologic cancer diagnosis, but similarly oncology rehab specialists may have qualms about dealing with pelvic health issues, with the result that these women fall through the cracks and do not have their pelvic health issues managed properly (or at all). Theodore Roosevelt once said ‘No one cares how much you know, until they know how much you care’ and this is especially relevant for oncology pelvic rehab. Often you may be the first clinician to ask about bladder, bowel or sexual function or dysfunction. An understanding of the effects of cancer treatments on the pelvis is important but so too is the wealth of information you may already have about bladder, bowel and sexual health as well as neuroscience and pain education.

The most important thing is to ask these women about their pelvic health concerns – the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship defined cancer survivorship as extending from ‘the time of diagnosis and for the balance of life’. An emphasis on quality of life has been emphasised – if we know that cancer survivors may not independently volunteer information about their pelvic floor dysfunction, it is our responsibility to ask the questions and comprehensively treat and advocate for these women, in order to help them live well after cancer treatment ends.

- Hazewinkel MH. Sprangers MA, Velden Jvd, Vaart CH, Stalpers LJ, Burger MP ‘Longterm cervical cancer survivors suffer from pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms: A cross-sectional matched cohort study’ Gynecol Oncol 2010;117(2):381-6

- Erekson EA, Sung VW, Disilvestro PA, Myers DL ‘Urinary symptoms and impact on quality of life in women after treatment for endometrial cancer’ Int Urogynecol J 2009;20(2):159-63

- Malone P, Danaher D, Galvin R, Cusack T ‘The patient’s voice: What are the views of women on living with pelvic floor problems following successful treatment for pelvic cancers?’ Physiotherapy Practice and Research 38(2017)93-102

Managing a medical crisis such as a cancer diagnosis can be overwhelming for an individual. Faced with choices about medical options, dealing with disruptions in work, home and family life often leaves little energy left to consider sexual health and intimacy. Maintaining closeness, however, is often a goal within a partnership and can aid in sustaining a relationship through such a crisis. The research is clear about cancer treatment being disruptive to sexual health, yet intimacy is a larger concept that may be fostered even when sexual activity is impaired or interrupted. Last year, when I was asked to speak to the Pacific NW Prostate Cancer Conference about intimacy, I was pleasantly surprised to find a rich body of literature about maintaining intimacy despite a diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

If the patient brings up sexual health, or we encourage the conversation, there are many research-based suggestions we can provide to encourage recovery of intimacy, several are listed below.

- Manage general health, fitness, nutrition, sleep, anxiety and stress

- Redefine sex as being beyond penetration, consider other sexual practices such as massage/touch, cuddling, talking, use of vibrators, medication, aids such as pumps (Usher et al., 2013)

- Participate in couples therapy to understand partners’ needs, address loss, be educated about sexual function (Wittman et al., 2014; Wittman et al., 2015)

- Participate in “sensate focus” activities (developed by Masters & Johnson in 1970’s as “touch opportunities”) with appropriate guidance (Weiner & Avery-Clark 2017)

Within the context of this information, there is opportunity to refer the patient to a provider who specializes in sexual health and function. While some rehabilitation professionals are taking additional training to be able to provide a level of sexual health education and counseling, most pelvic health providers do not have the breadth and depth of training required to provide counseling techniques related to sexual health- we can, however, get the conversation started, which in the end may be most important.

In the men’s health course, we further discuss sexual anatomy and physiology, prostate issues, and look at the research describing models of intimacy and what worked for couples who did learn to renegotiate intimacy after prostate cancer.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2009, April). Sexual intimacy in heterosexual couples after prostate cancer treatment: What we know and what we still need to learn. In Urologic oncology: seminars and original investigations (Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 137-143). Elsevier.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2013). Sexual Values as the Key to Maintaining Satisfying Sex After Prostate Cancer Treatment : The Physical Pleasure–Relational Intimacy Model of Sexual Motivation. Archives of sexual behavior, 42(8), 1637-1647.

Gilbert, E., Ussher, J. M., & Perz, J. (2010). Renegotiating sexuality and intimacy in the context of cancer: the experiences of carers. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(4), 998-1009.

Hawkins, Y., Ussher, J., Gilbert, E., Perz, J., Sandoval, M., & Sundquist, K. (2009). Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: the experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer nursing, 32(4), 271-280.

Higano, C. S. (2012). Sexuality and intimacy after definitive treatment and subsequent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(30), 3720-3725.

Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., Gilbert, E., Wong, W. T., & Hobbs, K. (2013). Renegotiating sex and intimacy after cancer: resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nursing, 36(6), 454-462.

Weiner, L., Avery-Clark, C. (2017). Sensate Focus in Sex Therapy: The Illustrated Manual. Routledge, New York.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., An, L., Palapattu, G., & Montie, J. E. (2014). Exploring the role of the partner in couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(9), 2509-2515.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., Crossley, H., An, L., ... & Montie, J. E. (2015). What couples say about their recovery of sexual intimacy after prostatectomy: toward the development of a conceptual model of couples' sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. The journal of sexual medicine, 12(2), 494-504.

When a woman is given a cancer diagnosis, her entire world is turned upside down and inside out. There are so many things to think about; medical treatments, financial concerns, family concerns, and emotional upheaval. Sex may be the last thing that a woman may think about when she is actively going through treatment. However, at what rate are survivors having issues after treatment is complete?

A recent study published in the journal Cancer looked at just this. A 2-year longitudinal study was performed that tracked young adults (18-39 years old) through and after their cancer diagnosis. The most common cancers seen in the samples were leukemia, breast cancer, soft-tissue sarcoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The patients completed the Medical Outcomes Study Sexual Functioning Scale at 4 months, 6 months, and 24 months after diagnosis. At 2 years after diagnosis over 50% of the patients surveyed reported some degree of sexual dysfunction. Women that were in a committed relationship had an increased likelihood for experiencing sexual dysfunction; while men had increased rate of reporting sexual issues regardless of their relationship status.

A recent study published in the journal Cancer looked at just this. A 2-year longitudinal study was performed that tracked young adults (18-39 years old) through and after their cancer diagnosis. The most common cancers seen in the samples were leukemia, breast cancer, soft-tissue sarcoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The patients completed the Medical Outcomes Study Sexual Functioning Scale at 4 months, 6 months, and 24 months after diagnosis. At 2 years after diagnosis over 50% of the patients surveyed reported some degree of sexual dysfunction. Women that were in a committed relationship had an increased likelihood for experiencing sexual dysfunction; while men had increased rate of reporting sexual issues regardless of their relationship status.

Women that undergo cancer treatment have several reasons that could be influencing their sexual function. Fatigue is a complaint that is often expressed by cancer patients. Their body image is often altered due to surgeries that have been performed. Chemotherapy and hormonal therapy often push women into menopause which then leads to vaginal dryness. Additionally, radiation and surgical treatment can lead to scar tissue, fibrosis, and stenosis of the vagina and pelvic floor muscles.

This is where physical therapy can help! In the Pelvic Floor Series Capstone course we teach advanced techniques that help treat pelvic floor issues by working on both the muscles, and the fascia. We also cover techniques that decrease the tenderness in the muscles that then allow you to stretch the muscle with less discomfort.

All of the techniques taught in Capstone are gentle but effective. The cancer survivor is the perfect population to use these gentle techniques on! Think of how rewarding our job will be when we help relieve the pain that may be associated with intercourse, and therefore improve intimacy of a cancer survivor with her partner!

Come join us for Capstone and learn techniques that will take your treatment skills to the next level!

Acquati, Zebrack, Faul, et al. Sexual functioning among young adult cancer patients: A 2-year longitudinal study. Cancer. 2018; 124(2): 398-405.

I love adding flax seed to my recipes when I bake. I even hide it in yogurt with crushed graham crackers for my kids. It is a powerful nutrient that can be consumed without knowing it! Although the specific mechanism for its efficacy on prostate health continues to be researched, studies over the last several years applaud flax seed for its benefits and encourage me to keep sneaking it in my family’s diet.

In 2008, Denmark-Wahnefried et al. performed a study to see if flax seed supplementation alone (rather than in combination with restricting dietary fat) could decrease the proliferation rate of prostate cancer prior to surgery. Basically, flax seed is a potent source of lignan, which is a phytoestrogen that acts like an antioxidant and can reduce testosterone and its conversion to dihydrotestosterone. It is also rich in plant-based omega-3 fatty acids. In this study, 161 prostate cancer patients, at least 3 weeks prior to prostatectomy, were divided into 4 groups: 1) normal diet (control); 2) 30g/day of flax seed supplementation; 3) low-fat diet; and 4) flax seed supplementation combined with low-fat diet. Results showed the rate of tumor proliferation was significantly lower in the flax seed supplemented group. The low-fat diet was proven to reduce serum lipids, consistent with previous research for cardiovascular health. The authors concluded, considering limitations in their study, flax seed is at least safe and cost-effective and warrants further research on its protective role in prostate cancer.

In 2008, Denmark-Wahnefried et al. performed a study to see if flax seed supplementation alone (rather than in combination with restricting dietary fat) could decrease the proliferation rate of prostate cancer prior to surgery. Basically, flax seed is a potent source of lignan, which is a phytoestrogen that acts like an antioxidant and can reduce testosterone and its conversion to dihydrotestosterone. It is also rich in plant-based omega-3 fatty acids. In this study, 161 prostate cancer patients, at least 3 weeks prior to prostatectomy, were divided into 4 groups: 1) normal diet (control); 2) 30g/day of flax seed supplementation; 3) low-fat diet; and 4) flax seed supplementation combined with low-fat diet. Results showed the rate of tumor proliferation was significantly lower in the flax seed supplemented group. The low-fat diet was proven to reduce serum lipids, consistent with previous research for cardiovascular health. The authors concluded, considering limitations in their study, flax seed is at least safe and cost-effective and warrants further research on its protective role in prostate cancer.

In 2017, de Amorim et al. investigated the effect of flax seed on epithelial proliferation in rats with induced benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). The 4 experimental groups consisting of 10 Wistar (outbred albino rats) rats each were as follows: 1) control group of healthy rats fed a casein-based diet (protein in milk); 2) healthy rats fed a flax seed-based diet; 3) hyperplasia-induced rats fed a casein diet; and 4) hyperplasia-induced rats fed a flax seed diet. Silicone pellets full of testosterone propionate were implanted subcutaneously in the rats to induce hyperplasia. Once euthanized at 20 weeks, the prostate tissue was examined for thickness and area of epithelium, individual luminal area, and total prostatic alveoli area. Results showed the hyperplasia induced rats fed a flax seed-based diet had smaller epithelial thickness as well as a reduced proportion of papillary projections found in the prostatic alveoli. These authors determined flax seed exhibits a protective role for the epithelium of the prostate in animals induced with BPH.

Bisson, Hidalgo, Simons, and Verbruggen2014 hypothesized a lignan-fortified diet could decrease the risk of BPH. The authors used an extract rich in lignan obtained from flax seed hulls. Four groups of 12 Wistar rats were used, with 1 negative control group and 3 groups with testosterone propionate (TP)-induced BPH (1 positive control, and 2 with diets containing 0.5% or 1.0% of the extract). Over a 5 week period, the 2 BPH-induced groups consuming the lignan extract starting 2 weeks prior to the BPH induction demonstrated a significant inhibition of prostate growth from the TP compared to the positive control group. These authors concluded the lignan-rich flax seed hull extract prevented BPH induction.

From BPH to prostate cancer, flax seed has proven a noteworthy supplement for preventative health. A tablespoon of flax seed in a muffin recipe is likely not a life-changing dose, but it’s a start. Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist enlightens practitioners with even more healthy choices, and Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation gives you the necessary tools to help patients recover from prostate cancer.

Demark-Wahnefried, W., Polascik, T. J., George, S. L., Switzer, B. R., Madden, J. F., Ruffin, M. T., … Vollmer, R. T. (2008). Flax seed Supplementation (not Dietary Fat Restriction) Reduces Prostate Cancer Proliferation Rates in Men Presurgery. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention : A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 17(12), 3577–3587. http://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0008

de Amorim Ribeiro, I.C., da Costa, C.A.S., da Silva, V.A.P. et al. (2017). Flax seed reduces epithelial proliferation but does not affect basal cells in induced benign prostatic hyperplasia in rats. European Journal of Nutrition. 56: 1201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-016-1169-1

Bisson JF, Hidalgo S, Simons R, Verbruggen M. 2014. Preventive effects of lignan extract from flax hulls on experimentally induced benign prostate hyperplasia. Journal of Medicinal Food. 17(6): 650-656. http://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2013.0046

It’s St Valentine’s day this week – you may have noticed hearts and flowers everywhere you look and a general theme of love and romance. For many women going through cancer treatment, sex may be the last thing on their mind…or not! Women who are going through treatment for gynecologic cancer are often handed a set of dilators with minimal instruction on how to use them, or as one patient reported, they are told to have sex three or four times a week during radiation therapy ‘to keep your vagina patent’. As a pelvic rehab practitioner with a special interest in oncology rehab, I know that we can (we must!) do better, in helping women live well after cancer treatment ends.

As Susan Gubar, an ovarian cancer survivor, writes in the New York Times ‘…It can be difficult to experience desire if you don’t love but fear your body or if you cannot recognize it as your own. Surgical scars, lost body parts and hair, chemically induced fatigue, radiological burns, nausea, hormone-blocking medications, numbness from neuropathies, weight gain or loss, and anxiety hardly function as aphrodisiacs…’

As Susan Gubar, an ovarian cancer survivor, writes in the New York Times ‘…It can be difficult to experience desire if you don’t love but fear your body or if you cannot recognize it as your own. Surgical scars, lost body parts and hair, chemically induced fatigue, radiological burns, nausea, hormone-blocking medications, numbness from neuropathies, weight gain or loss, and anxiety hardly function as aphrodisiacs…’

Although sexual changes can be categorised into physical, psychological and social, the categories cannot be neatly delineated in the lived experience (Malone at al 2017). The good news? Pelvic rehab therapists not only have the skills to enhance pelvic health after cancer treatment and are ideally positioned to be able to take a global and local approach to the sexual health difficulties women may face after cancer treatment ends, but there is also a good and growing body of evidence to support the work we do. Factors to consider include physical issues leading to dyspareunia, including musculo-skeletal/ orthopaedic, Psychological issues, including loss of libido and other pelvic health issues impacting sexual function such as faecal/ urinary incontinence, pain or fatigue.

In Hazewinkel’s 2010 paper, women reported that they thought their physicians would tell them if solutions were available…most reported reasons for not seeking help were that women found their symptoms bearable in the light of their cancer diagnosis and lacked knowledge about possible treatments but when informed of possible treatment strategies ‘…women stated that care should be improved, specifically by timely referral to pelvic floor specialists’. The good news: ‘‘Pelvic Floor Rehab Physiotherapy is effective even in gynecological cancer survivors who need it most.’ (Yang 2012)

The issue therefore may be one of awareness – for both the women who need our services and the physicians and healthcare team who work in the field of gynecologic oncology. What we need is acknowledgement of the issues and confident conversation and assessment by clinicians – interested in learning more? Come and join the conversation in Tampa next month at my Oncology & the Female Pelvic Floor course!

‘Sex after Cancer’ by Susan Gubar, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/18/well/live/sex-after-cancer.html

Malone et al 2017: ‘‘The patient’s voice: What are the views of women on living with pelvic floor problems following successful treatment for pelvic cancers?’

Hazewinkel et al 2010 ‘Reasons for not seeking medical help for severe pelvic floor symptoms: a qualitative study in survivors of gynaecological cancer’

Interstitial cystitis is a chronic pain condition characterized by both pelvic pain and urinary symptoms. It’s diagnosed by unexplained pain or pressure that is perceived to be related to the bladder, and affects more than 12 million Americans. It’s often described as the sensation of a urinary tract infection, but without any bacterial infection. Many patients report severe pain, often more intense than that associated with bladder cancer, and up to 85% of patients have accompanying pelvic floor dysfunction.

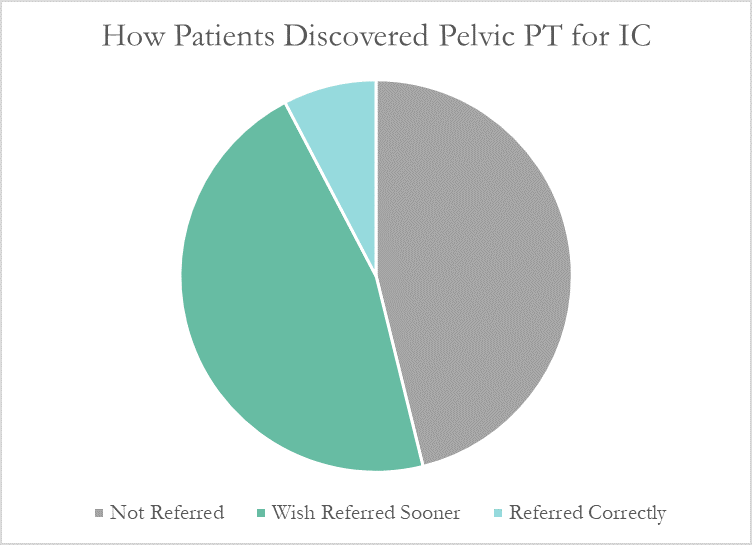

Pelvic floor physical therapy is the most proven treatment for interstitial cystitis. It’s recommended by the American Urological Association (AUA) as a first-line medical treatment in their IC Guidelines, and is the only treatment given an evidence grade of ‘A’. Furthermore, it’s the sole intervention that provides sustained relief; bladder treatments and oral medications must be continued indefinitely to provide benefit, if they work at all.

Research has demonstrated that at least 85% of patients with interstitial cystitis also have pelvic floor dysfunction. In fact, many of the symptoms of IC can only be explained by the pelvic floor. The majority of patients report painful intercourse, low back pain, hip pain, or constipation accompanying the condition; symptoms that have nothing to do with the bladder.

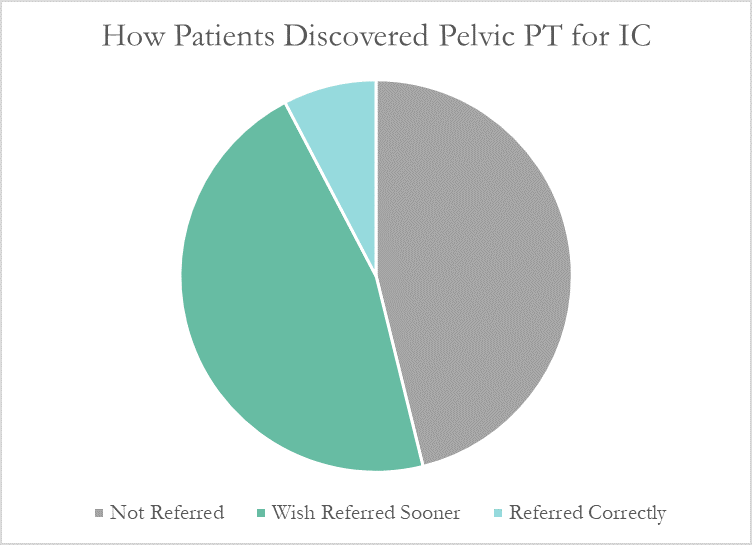

Despite this, many patients don’t learn about pelvic floor physical therapy for years after their diagnosis. Many have to discover pelvic PT for themselves, or their doctor only mentions physical therapy as a last resort. At PelvicSanity, we just published a study of our interstitial cystitis patients in the International Pelvic Pain Society (IPPS) meeting, reporting on both patient outcomes and their experience with the medical system following their IC diagnosis.

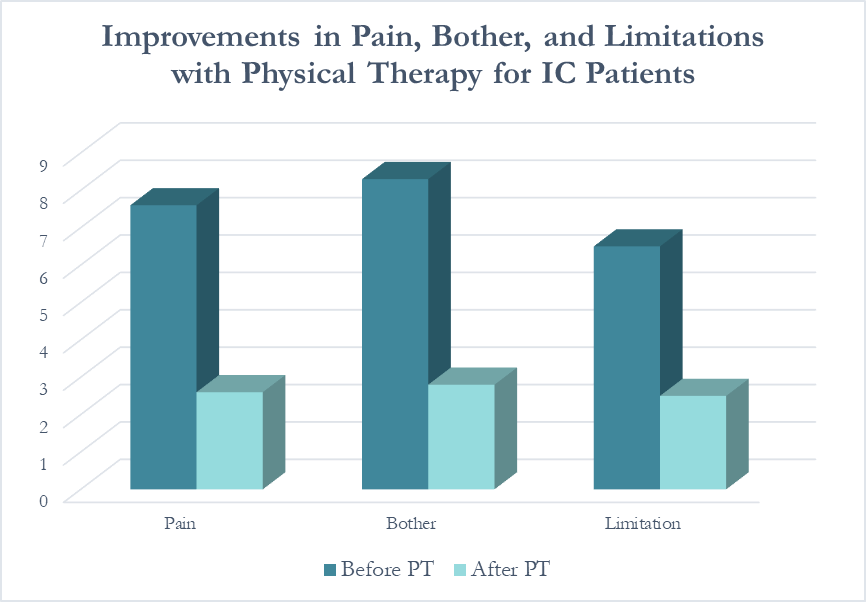

In following the results for thirteen consecutive patients with an interstitial cystitis diagnosis, patients reported more than a 60% improvement in pain, symptom bother, and how much symptoms limited their daily activities. On average, their pain level was at a 7.6 out of 10 upon initial evaluation, which fell to 2.6 after treatment.

Patients saw a relatively rapid improvement in their symptoms with treatment. Over half (54%) reported an improvement in symptoms within their first three visits; 31% saw their first improvement in visits 4-6 and 15% required ten or more visits for subjective improvement. Importantly, all patients in the study reported a better understanding of their condition and feeling more hopeful for recovery after their initial evaluation.

Patients saw a relatively rapid improvement in their symptoms with treatment. Over half (54%) reported an improvement in symptoms within their first three visits; 31% saw their first improvement in visits 4-6 and 15% required ten or more visits for subjective improvement. Importantly, all patients in the study reported a better understanding of their condition and feeling more hopeful for recovery after their initial evaluation.

More than half of these patients reported seeing five or more medical doctors for their condition prior to beginning pelvic floor physical therapy, and had been prescribed multiple medications and undergone bladder treatments without success. However, only a single respondent (7.7%) believed they had been referred to pelvic PT by their doctor at the appropriate time. Nearly half (46%) had to find out about pelvic floor physical therapy for interstitial cystitis themselves, while the remainder felt they had been referred by their doctor far too late, as a last resort.

With more than 12 million women and men suffering with this condition in the United States alone, increasing education – for both doctors and patients – is vital. In our upcoming course for physical therapists in treating interstitial cystitis (April 28-29, 2018 in San Diego), we’ll focus on the most important physical therapy techniques for IC, home stretching and self-care programs, and information to guide patients in creating a holistic treatment plan

Curing cancer but not addressing life-altering complications can be compared to feeding the homeless on Thanksgiving but turning your back on them the rest of the year. We love hearing positive outcomes of a surgery, but we are not always aware of what happens beyond that. Colorectal cancer is often treated by colectomy, and sometimes the survivor of cancer is left with urological or sexual dysfunction, small bowel obstruction, or pelvic lymphedema.

Panteleimonitis et al., (2017) recognized the prevalence of urological and sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery and compared robotic versus laparoscopic approaches to see how each impacted urogenital function. In this study, 49 males and 29 females underwent laparoscopic surgery, and 35 males and 13 females underwent robotic surgery. Prior to surgery, 36 men and 9 women were sexually active in the first group and 13 men and 4 women were sexually active in the latter group. Focusing on the male results, male urological function (MUF) scores were worse pre-operatively in the robotic group for frequency, nocturia, and urgency compared to the laparoscopic group. Post-operatively, urological function scores improved in all areas except initiation/straining for the robotic group; however, the MUF median scores declined in the laparoscopic group. Regarding male sexual function (MSF) scores for libido, erection, stiffness for penetration and orgasm/ ejaculation, the mean scores worsened in all areas for the laparoscopic group but showed positive outcomes for the robotic group. In spite of limitations of the study, the authors concluded robotic rectal cancer surgery may afford males and females more promising urological and sexual outcomes as robotic.

Panteleimonitis et al., (2017) recognized the prevalence of urological and sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery and compared robotic versus laparoscopic approaches to see how each impacted urogenital function. In this study, 49 males and 29 females underwent laparoscopic surgery, and 35 males and 13 females underwent robotic surgery. Prior to surgery, 36 men and 9 women were sexually active in the first group and 13 men and 4 women were sexually active in the latter group. Focusing on the male results, male urological function (MUF) scores were worse pre-operatively in the robotic group for frequency, nocturia, and urgency compared to the laparoscopic group. Post-operatively, urological function scores improved in all areas except initiation/straining for the robotic group; however, the MUF median scores declined in the laparoscopic group. Regarding male sexual function (MSF) scores for libido, erection, stiffness for penetration and orgasm/ ejaculation, the mean scores worsened in all areas for the laparoscopic group but showed positive outcomes for the robotic group. In spite of limitations of the study, the authors concluded robotic rectal cancer surgery may afford males and females more promising urological and sexual outcomes as robotic.

Husarić et al., (2016) considered the risk factors for adhesive small bowel obstruction (SBO) after colorectal cancer colectomy, as SBO is a common morbidity that causes a decrease in quality of life. They performed a retrospective study of 248 patients who underwent colon cancer surgery, and 13.7% of all the patients had SBO. Thirty (14%) of the 213 males and 9 (12.7%) of the 71 females had SBO; consequently, they found patients being >60 years old was a more significant risk factor than sex regarding occurrence of SBO. The authors concluded a Tumor-Node Metastasis stage of >3 and immediate postoperative complications were found to be the greatest risk factors for SBO.

Vannelli et al., (2013) explored the prevalence of pelvic lymphedema after lymphadenectomy in patients treated surgically for rectal cancer. Five males and 8 females were examined one week before and 12 months after being discharged from the hospital. All 9 of the patients (4 males, 5 females) with extra-peritoneal cancer exhibited lymphedema via MRI, but the 4 (1 male, 3 females) patients with intra-peritoneal cancer had none. The authors concluded pelvic lymphedema can be elusive after rectal surgery, but pelvic disorders persist and patients should be routinely examined for it.

Obviously saving a life is the primary goal when it comes to cancer. But just like caring for the destitute for one day doesn’t cure a lifetime of hunger, ignoring the negative post-surgical sequelae of a colectomy prevents a cancer survivor from living a healthy life. Herman & Wallace offers two pelvic floor oncology courses, “Oncology and the Male Pelvic Floor” and "Oncology and the Female Pelvic Floor" , which address how pelvic cancers affect the quality of life of our patients and how practitioners can make a positive impact.

Panteleimonitis, S., Ahmed, J., Ramachandra, M., Farooq, M., Harper, M., & Parvaiz, A. (2017). Urogenital function in robotic vs laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery: a comparative study. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 32(2), 241–248. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-016-2682-7

Husarić E., Hasukić Š, Hotić N, Halilbašić A, Husarić S, Hasukić I. (2016). Risk factors for post-colectomy adhesive small bowel obstruction. Acta

When I work prn in inpatient rehabilitation, I have access to each patient’s chart and can really focus on the systems review and past medical history, which often gives me ample reasons to ask about pelvic floor dysfunction. So, of course, I do. I have yet to find a gynecological cancer survivor who does not report an ongoing struggle with urinary incontinence. And sadly, they all report that they just deal with it.

Bretschneider et al.2016 researched the presence of pelvic floor disorders in females with presumed gynecological malignancy prior to surgical intervention. Baseline assessments were completed by 152 of the 186 women scheduled for surgery. The rate of urinary incontinence (UI) at baseline was 40.9% for the subjects, all of whom had uterine, ovarian, or cervical cancer. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) was reported by 33.3% of the women, urge incontinence (UI) by 25%, fecal incontinence (FI) by 3.9%, abdominal pain by 47.4%, constipation by 37.7%, and diarrhea by 20.1%. The authors concluded pelvic floor disorders are prevalent among women with suspected gynecologic cancer and should be noted prior to surgery in order to provide more thorough rehabilitation for these women post-operatively.

Bretschneider et al.2016 researched the presence of pelvic floor disorders in females with presumed gynecological malignancy prior to surgical intervention. Baseline assessments were completed by 152 of the 186 women scheduled for surgery. The rate of urinary incontinence (UI) at baseline was 40.9% for the subjects, all of whom had uterine, ovarian, or cervical cancer. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) was reported by 33.3% of the women, urge incontinence (UI) by 25%, fecal incontinence (FI) by 3.9%, abdominal pain by 47.4%, constipation by 37.7%, and diarrhea by 20.1%. The authors concluded pelvic floor disorders are prevalent among women with suspected gynecologic cancer and should be noted prior to surgery in order to provide more thorough rehabilitation for these women post-operatively.

Ramaseshan et al.2017 performed a systematic review of 31 articles to study pelvic floor disorder prevalence among women with gynecologic malignant cancers. Before treatment of cervical cancer, the prevalence of SUI was 24-29% (4-76% post-treatment), UI was 8-18% (4-59% post-treatment), and FI was 6% (2-34% post- treatment). Cervical cancer treatment also caused urinary retention (0.4-39%), fecal urge (3-49%), dyspareunia (12-58%), and vaginal dryness (15-47%). Uterine cancer showed a pre-treatment prevalence of SUI (29-36%), UUI (15-25%), and FI (3%) and post-treatment prevalence of UI (2-44%) and dyspareunia (7-39%). Vulvar cancer survivors had post-treatment prevalence of UI (4-32%), SUI (6-20%), and FI (1-20%). Ovarian cancer survivors had prevalence of SUI (32-42%), UUI (15-39%), prolapse (17%) and sexual dysfunction (62-75%). The authors concluded pelvic floor dysfunction is prevalent among gynecologic cancer survivors and needs to be addressed.

Lindgren, Dunberger, & Enblom2017 explored how gynecological cancer survivors (GCS) relate their incontinence to quality of life, view their physical activity/exercise ability, and perceive pelvic floor muscle training. The authors used a qualitative interview content analysis study with 13 women, age 48–82. Ten women had UI and 3 had FI after treatment (2 had radiation therapy, 5 had surgery, and 6 had surgery as well as radiation therapy). The results showed a reduction in physical and psychological quality of life and sexual activity because of incontinence. Having minimal to no experience or even awareness of pelvic floor training, 9 out of the 10 women were willing to spend 7 hours a week to improve their incontinence. Practical and emotional coping strategies also helped these women, and they all declared they had the cancer treatments without being informed of the risk of incontinence, which impacted their attitude and means of handling the situation.

Research shows incontinence is a common occurrence after gynecological cancer treatment. It impacts quality of life after surviving a serious illness, and many women do not know pelvic floor therapy can improve their situation. Oncology and the Female Pelvic Floor is an ideal course for practitioners to take to help increase their knowledge on how to educate and treat this population.

Bretschneider, C. E., Doll, K. M., Bensen, J. T., Gehrig, P. A., Wu, J. M., & Geller, E. J. (2016). Prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in women with suspected gynecological malignancy: a survey-based study. International Urogynecology Journal, 27(9), 1409–1414. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-2962-3

Ramaseshan, A.S., Felton, J., Roque, D., Rao, G., Shipper, A.G., Sanses, T.V.D. (2017). Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: a systematic review. International Urogynecology Journal. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3467-4

Lindgren, A., Dunberger, G., & Enblom, A. (2017). Experiences of incontinence and pelvic floor muscle training after gynaecologic cancer treatment. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(1), 157–166. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3394-9

Summer can make women cringe at the thought of baring most of their bodies yet finding just the right coverage for their breasts. Some scrounge for padded tops to pump up their actual A cup. Some seek the greatest amount of coverage to support every ounce of skin. And still others search for flattering tops to accentuate cleavage and minimize tan lines. Just like one swimsuit does not fit every woman, only one aspect of post-breast cancer rehab is not generally sufficient. A combination of exercise, mindfulness, and myofascial release may need to be implemented for optimal recovery.

Ibrahim et al., (2017) produced a pilot randomized controlled trial considering the effects of specific exercise on upper limb function and ability to return to work after radiotherapy for breast oncology. The study involved 59 young women divided into an exercise group or a control group that received standard care. The Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH), the Metabolic Equivalent of Task-hours per week (MET-hours/week), and a post hoc questionnaire on return to work were all used and recorded over 6 time periods after the 12-week post-radiation targeted exercise program. Women who had a total mastectomy still had upper limb dysfunction, but no there was no statistically significant difference in DASH scores between groups. Both groups at 18 months had returned to their pre-illness activity levels, and 86% returned to work (at just 8.5 fewer hours/week). The authors concluded exercise alone does not change the long-term outcome of upper limb function post-radiation.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for persistent pain in women after treatment for primary breast cancer was explored by Johannsen et al., in two 2017 articles, one concerned with clinical and psychological mediators and the other focused on cost-effectiveness. Each study included 129 women with persistent pain from breast cancer, placed in a MBCT group or a wait-list control group. The first study showed attachment avoidance was a statistically significant moderator, with subjects who had a higher attachment avoidance having lower pain intensity after MBCT. In the subjects undergoing radiotherapy, MBCT had a smaller effect on pain than those not having radiotherapy. The authors’ next study focused on the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) on pain intensity. Baseline and 6 months post-treatment data on healthcare utilization and pain medication were analyzed from national registries. The average total cost of the MBCT group was 730 euros less than the control group, and more women in the MBCT group had a MCID in pain than those in the control group.

DeGroef et al., (2017) performed a randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of myofascial techniques for breast cancer survivors who experienced upper limb dysfunctions. Fifty women post-unilateral breast cancer received either 12 sessions of standard physical therapy with myofascial therapy or 12 sessions of standard physical therapy plus a sham intervention during a 3-month period. After intervention, no significant differences between groups were found for active shoulder range of motion, lymphedema, handheld dynamometer strength, scapular statics and dynamics, shoulder function, or quality of life. The authors concluded shoulder ROM and function in both groups showed positive effects up to 1 year follow-up, but myofascial therapy provided no additional benefit in breast cancer patients.

Treatment for any patient should be individualized, based on deficits found clinically, whether they are physiological, anatomical, or psychological. Having a beach bag overflowing with techniques and tools, each ready to be used when the appropriate time comes, makes for a more competent therapist and a better rehabilitation outcome for patients. There simply is no “one size fits all” in breast oncology rehab.

YOU can be a major contributor to a breast cancer patients medical care team. Learn new skills by attending Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient this September in Boston, MA.

Ibrahim, M, Muanza, T, Smirnow, N, Sateren, W, Fournier, B, Kavan, P, Palumbo, M, Dalfen, R, Dalzell, MA. (2017). Time course of upper limb function and return-to-work post-radiotherapy in young adults with breast cancer: a pilot randomized control trial on effects of targeted exercise program. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: research and practice. http://doi:10.1007/s11764-017-0617-0

Johannsen, M, O'Toole, MS, O'Connor, M, Jensen, AB, Zachariae, R. (2017). Clinical and psychological moderators of the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on persistent pain in women treated for primary breast cancer - explorative analyses from a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncology. 56(2):321-328. http://doi:10.1080/0284186X.2016.1268713

Johannsen, M, Sørensen, J, O'Connor, M, Jensen, AB, Zachariae, R. (2017). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is cost-effective compared to a wait-list control for persistent pain in women treated for primary breast cancer-Results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. http://doi:10.1002/pon.4450

De Groef,A, Van Kampen, M, Verlvoesem N, Dieltjens, E, Vos, L, De Vrieze, T, Christiaen, MR, Neven, P, Geraerts, I, Devoogdt, N. (2017). Effect of myofascial techniques for treatment of upper limb dysfunctions in breast cancer survivors: randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 25(7):2119-2127. http://doi:10.1007/s00520-017-3616-9