Tara Sullivan, PT, DPT, PRPC, WCS, IF sat down with Holly Tanner and The Pelvic Rehab Report to discuss her course, Sexual Medicine in Pelvic Rehab. Tara started in the healthcare field as a massage therapist, practicing for over ten years including three years of teaching massage and anatomy, and physiology. Tara has specialized exclusively in Pelvic Floor Dysfunction treating bowel, bladder, sexual dysfunctions, and pelvic pain since 2012.

Hi Tara, can you introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about your background?

Sure! So I’m Tara. I’ve been a pelvic health rehab therapist for about 10 years now. I started right out of PT school and I got a job at a local hospital where they were looking to grow and build the pelvic rehab program. So of course, I found Herman & Wallace and started taking all of the classes there that I could and just kept learning over the years. Now the program is expanded across the valley, we have nine different locations, and it’s been very successful and fulfilling. It’s my passion.

Recently, I would say the past four to five years of my career, I’ve started getting more into sexual dysfunctions. I was always into pelvic floor dysfunction in general - bowel, bladder, sexual dysfunction, and chronic pelvic pain, but I didn’t get specifically into the sexual medicine side of it until recently. I did the fellowship with ISSWSH that really pulled all of that information together with what I’ve learned through the years.

Can you explain what ISSWSH is and how that combined with the knowledge base that you already had?

I feel like ISSWSH for me, where I came full circle. I finally was like “I get it.” ISSWSH is the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and it’s all the gurus like Dr. Goldstein, Rachel Rubin, and Susan Kellogg that have been around forever doing the research on sexual medicine. I started attending their conferences, became a faculty member, and presented at their annual fall meeting here in Scottsdale. Then I ended up doing their fellowship. Every year I would attend the conference, but it took a couple of years for all of that knowledge to soak in and for me to be able to really apply it. For example, that patient with that sticky discharge, maybe that is lichen planus – that’s the kind of medical side that you don’t necessarily learn in physical therapy school.

That for me just really helped my differential diagnosis which means that you can get the patient’s care faster. Get them to that resolution faster because you are working with a team of people and we all have our roles. As PTs and rehab practitioners, we have the time to sit with our patients. We are so blessed to have an hour, and the medical doctors don’t, for us to really take that time to figure out the patient’s history and what they’ve been through, and what could be the cause of it. We have the time to be the detective and help them get the care they need. Whether it’s with us, or in conjunction with something else. My goal is to never tell someone that I can’t help them because it’s not muscular.

How has this knowledge helped you in your collaboration with other practitioners in your practice?

I feel like this knowledge was the missing link for me. It brings it all together for the patient. So the patients come here and the urologist says “that’s not my area,” and then the gynecologist says “that’s not my area.” Then they come to you and you’re like “it’s kind of my area, but I can’t prescribe the medication that you need.”

My practice got so much better, just in the sense of the overall quality of care, when I was able to develop those relationships with the doctors. I could pick up the phone and say “Hey, that patient that you sent me – I think they have vestibulodynia, and I think it’s from their long-term use of oral contraceptive pills. I think that they might benefit from some local estrogen testosterone cream.” They would say, I don’t know about that, and I’d respond “let me send you some articles. Let me tell you what I’ve learned.”

Now I can just pick up the phone or send them a text asking them to prescribe so and so. It really helped bridge that gap. The doctors now will say “Ok. I know something’s going on, but I don’t know if it’s muscular or tissue. I don’t have that training, what do you think?” So it’s just been such a collaboration, it’s been so great. Then I’ll go the reverse of that and watch them do a surgery, watch them do a procedure.

For our patients, we need to take that time and work with the physicians and develop that relationship with them, because it’s easy to pass it off as “that’s not my job.” Especially the vestibule! The gynecologist goes right through it and looks into the vaginal canal and then the urologist is like I’m going to look at the urethra but I’m not looking around it, let me just stick that scope in. This knowledge and ability to use differential diagnosis, for me just brings it all together.

Does your course have an online, pre-recorded portion as well as a live component?

Yes. There are about nine lab videos on manual techniques because everyone wants to know what to do. For me, it’s more about what you know. What can you identify and differentiate with the differential diagnosis. Then we have about two hours of just the basic lectures on general pain and overactivity of the pelvic floor so that we can spend our time in the live lecture getting into the very specific conditions that we as PTs are, not necessarily diagnosing, but recognizing and sending for further care. That’s really where I wanted this class to fill the gap between the urologist, the gynecologist, and the PT.

Is your course primarily vulvo-vaginal conditions or are there some penile, scrotal, or other conditions?

It is both male and female dysfunctions, and I have a few transgender cases. I don’t personally treat the transgender population very often so I only have a couple of examples of that. I have a lot of examples where I’m trying to get practitioners to recognize the problem by what the patient is saying and their history, and how to funnel this into their differential diagnosis. Case studies include different types of vestibulodynia and causes, all the different skin conditions…and it’s not necessarily something that they didn’t learn in one of the Pelvic Floor Series courses, but I wanted one class where they could just talk about all the sexual dysfunctions and get into some of the ones that we don’t see as often but are present.

We also talk about PGAD (persistent genital arousal disorder), and with male dysfunctions, we talk about spontaneous ejaculation and urethral discharge, post finasteride syndrome. All of these things that you might not see every day, but when you see them you’ll recognize them so that you can help patients talk to the doctor and get the proper care. There are a lot of random, not as obvious, conditions that are not as prevalent. Then there are the common conditions that we see every single day like lichens.

What is the biggest takeaway that practitioners have who come into your class?

It is really being able to access and effectively use differential diagnosis. A lot of practitioners in the course are like “I always wondered what that was.” I have a ton of pictures that I share, and I’m like, I know have seen this before. I think a lot of it is the differential diagnosis. The feedback that I get from every class is “I feel like I can go to the clinic on Monday and apply what I learned.” “I’m going to go buy a q-tip and start doing a q-tip test because now I know what to do with that information.” They feel that confidence of really being able to apply it, talk to the patient, talk to the doctors, and figure out that meaningfulness.

Sexual Medicine in Pelvic Rehab

Course Dates:

January 14-15, 2023

May 13-14, 2023

September 23-24, 2023

Price: $450

Experience Level: Beginner

Contact Hours: 15

Description: This two-day course provides a thorough introduction to pelvic floor sexual function, dysfunction, and treatment interventions, as well as an evidence-based perspective on the value of physical therapy interventions for patients with chronic pelvic pain related to sexual conditions, disorders, and multiple approaches for the treatment of sexual dysfunction including understanding medical diagnosis and management.

Lecture topics include hymen myths, squirting, G-spot, prostate gland, sexual response cycles, hormone influence on sexual function; the anatomy and physiology of pelvic floor muscles in sexual arousal, orgasm, and function, and specific dysfunction treated by physical therapy in detail. Including vaginismus, dyspareunia, erectile dysfunction, hard flaccid, prostatitis, and post-prostatectomy, as well as recognizing medical conditions such as persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD), hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), and dermatological conditions such as lichen sclerosis and lichen planus. Upon completion of the course, participants will be able to confidently treat sexual dysfunction related to the pelvic floor as well as refer to medical providers as needed and instruct patients in the proper application of self-treatment and diet/lifestyle modifications.

Course Reviews:

- The instructor offered excellent examples of what can be seen in the patient population and advised good treatment plans to help. She was very thorough in answering questions and very well-informed on all topics presented in this class. I was so thankful to learn more about the hormone component of pelvic floor rehab, as I feel that this is greatly lacking in the Midwest -- we still live on the idea that hormones and HRT are BAD! Looks like I will be doing some heavy marketing soon with research articles! Thank you so much for all of this information!

- Various topics only glossed over in other courses were covered in detail to meet the various levels of knowledge of all students in the class. On top of this, new and useful material was also introduced and explained very well.

- Tara gave practical tips for us to start using in clinical practice and her notes to her lecture were KEY!

The following is an excerpt from the short interview between Holly Tanner and Tara Sullivan discussing her course Sexual Medicine in Pelvic Rehab. Watch the full video on the Herman & Wallace YouTube Channel.

Hi Tara, can you introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about your background?

Sure! So I’m Tara. I’ve been a pelvic health rehab therapist for about 10 years now. I started right out of PT school and I got a job at a local hospital where they were looking to grow and build the pelvic rehab program. So of course, I found Herman & Wallace and started taking all of the classes there that I could and just kept learning over the years. Now the program is expanded across the valley, we have nine different locations, and it’s been very successful and fulfilling. It’s my passion.

Recently, I would say the past four to five years of my career, I’ve started getting more into sexual dysfunctions. I was always into pelvic floor dysfunction in general - bowel, bladder, sexual dysfunction, and chronic pelvic pain, but I didn’t get specifically into the sexual medicine side of it until recently. I did the fellowship with ISSWSH that really pulled all of that information together with what I’ve learned through the years.

Can you explain what ISSWSH is and how that combined with the knowledge base that you already had?

I feel like ISSWSH for me, where I came full circle. I finally was like “I get it.” ISSWSH is the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and it’s all the gurus like Dr. Goldstein, Rachel Rubin, and Susan Kellogg that have been around forever doing the research on sexual medicine. I started attending their conferences, became a faculty member, and presented at their annual fall meeting here in Scottsdale. Then I ended up doing their fellowship. Every year I would attend the conference, but it took a couple of years for all of that knowledge to soak in and for me to be able to really apply it. For example, that patient with that sticky discharge, maybe that is lichen planus – that’s the kind of medical side that you don’t necessarily learn in physical therapy school.

That for me just really helped my differential diagnosis which means that you can get the patient’s care faster. Get them to that resolution faster because you are working with a team of people and we all have our roles. As PTs and rehab practitioners, we have the time to sit with our patients. We are so blessed to have an hour, and the medical doctors don’t, for us to really take that time to figure out the patient’s history and what they’ve been through, and what could be the cause of it. We have the time to be the detective and help them get the care they need. Whether it’s with us, or in conjunction with something else. My goal is to never tell someone that I can’t help them because it’s not muscular.

How has this knowledge helped you in your collaboration with other practitioners in your practice?

I feel like this knowledge was the missing link for me. It brings it all together for the patient. So the patients come here and the urologist says “that’s not my area,” and then the gynecologist says “that’s not my area.” Then they come to you and you’re like “it’s kind of my area, but I can’t prescribe the medication that you need.”

My practice got so much better, just in the sense of the overall quality of care, when I was able to develop those relationships with the doctors. I could pick up the phone and say “Hey, that patient that you sent me – I think they have vestibulodynia, and I think it’s from their long-term use of oral contraceptive pills. I think that they might benefit from some local estrogen testosterone cream.” They would say, I don’t know about that, and I’d respond “let me send you some articles. Let me tell you what I’ve learned.”

Now I can just pick up the phone or send them a text asking them to prescribe so and so. It really helped bridge that gap. The doctors now will say “Ok. I know something’s going on, but I don’t know if it’s muscular or tissue. I don’t have that training, what do you think?” So it’s just been such a collaboration, it’s been so great. Then I’ll go the reverse of that and watch them do a surgery, watch them do a procedure.

For our patients, we need to take that time and work with the physicians and develop that relationship with them, because it’s easy to pass it off as “that’s not my job.” Especially the vestibule! The gynecologist goes right through it and looks into the vaginal canal and then the urologist is like I’m going to look at the urethra but I’m not looking around it, let me just stick that scope in. This knowledge and ability to use differential diagnosis, for me just brings it all together.

Does your course have an online, pre-recorded portion as well as a live component?

Yes. There are about nine lab videos on manual techniques because everyone wants to know what to do. For me, it’s more about what you know. What can you identify and differentiate with the differential diagnosis. Then we have about two hours of just the basic lectures on general pain and overactivity of the pelvic floor so that we can spend our time in the live lecture getting into the very specific conditions that we as PTs are, not necessarily diagnosing, but recognizing and sending for further care. That’s really where I wanted this class to fill the gap between the urologist, the gynecologist, and the PT.

Is your course primarily vulvo-vaginal conditions or are there some penile, scrotal, or other conditions?

It is both male and female dysfunctions, and I have a few transgender cases. I don’t personally treat the transgender population very often so I only have a couple of examples of that. I have a lot of examples where I’m trying to get practitioners to recognize the problem by what the patient is saying and their history, and how to funnel this into their differential diagnosis. Case studies include different types of vestibulodynia and causes, all the different skin conditions…and it’s not necessarily something that they didn’t learn in one of the Pelvic Floor Series courses, but I wanted one class where they could just talk about all the sexual dysfunctions and get into some of the ones that we don’t see as often but are present.

We also talk about PGAD (persistent genital arousal disorder), and with male dysfunctions, we talk about spontaneous ejaculation and urethral discharge, post vasectomy syndrome. All of these things that you might not see every day, but when you see them you’ll recognize them so that you can help patients talk to the doctor and get the proper care. There are a lot of random, not as obvious, conditions that are not as prevalent. Then there are the common conditions that we see every single day like lichens.

What is the biggest takeaway that practitioners have who come into your class?

It is really being able to access and effectively use differential diagnosis. A lot of practitioners in the course are like “I always wondered what that was.” I have a ton of pictures that I share, and I’m like, I know you guys have seen this before. I think a lot of it is the differential diagnosis. The feedback that I get from every class is “I feel like I can go to the clinic on Monday and apply what I learned.” “I’m going to go buy a q-tip and start doing a q-tip test because now I know what to do with that information.” They feel that confidence of really being able to apply it, talk to the patient, talk to the doctors, and figure out that meaningfulness.

2022 Course Dates:

July 16-17 2022 and October 15-16 2022

Sexual Medicine in Pelvic Rehab is designed for pelvic rehab specialists who want to expand their knowledge, experience, and treatment in sexual health and dysfunction. This course provides a thorough introduction to pelvic floor sexual function, dysfunction, and treatment interventions for all people and sexual orientations, as well as an evidence-based perspective on the value of physical therapy interventions for patients with chronic pelvic pain related to sexual conditions, disorders, as well as multiple approaches for the treatment of sexual dysfunction including understanding medical diagnosis and management.

Lecture topics include hymen myths, female squirting, G-spot, prostate gland, female and male sexual response cycles, hormone influence on sexual function, anatomy and physiology of pelvic floor muscles in sexual arousal, orgasm, and function and specific dysfunction treated by physical therapy in detail including vaginismus, dyspareunia, erectile dysfunction, hard flaccid, prostatitis, post-prostatectomy, as well as recognizing medical conditions such as persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD), hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and dermatological conditions such as lichen sclerosis and lichen planus. Upon completion of the course, participants will be able to confidently treat sexual dysfunction related to the pelvic floor as well as refer to medical providers as needed and instruct patients in the proper application of self-treatment and diet/lifestyle modifications.

Audience:

This continuing education course is appropriate for physical therapists, occupational therapists, physical therapist assistants, occupational therapist assistants, registered nurses, nurse midwives, and other rehabilitation professionals of all levels and experience. Content is not intended for use outside the scope of the learner's license or regulation. Physical therapy continuing education courses should not be taken by individuals who are not licensed or otherwise regulated, except, as they are involved in a specific plan of care.

Ultrasound imaging is being used more frequently in the physical therapy clinical setting. Physical therapists are using ultrasound (US) imaging in varying ways. Some are using it as a training tool for the patient to learn neuromuscular control. Others are using it to guide needle placement while performing dry needling. In a recent article authored by several well-known physiotherapists, the various uses of US imaging were defined, as well as discussions regarding the scope of practice, and training for physiotherapists using ultrasound imaging.

Four uses of US imaging have been reported by physical therapists. The first and most common use of US imaging is the evaluation of muscle structure and function to aid in neuromuscular control. Essentially, the US images are being used as a source of biofeedback. This has been coined Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging (RUSI). Additional uses have emerged in recent years including Diagnostic US imaging which is the diagnosis and monitoring of pathology; and interventional US imaging which is using the US images to guide percutaneous procedures involving dry or wet needling. These three categories are performed during clinical care and fall under the umbrella term “point of care ultrasound.” The last category of US imaging use in physical therapy is paired with performing research.

Four uses of US imaging have been reported by physical therapists. The first and most common use of US imaging is the evaluation of muscle structure and function to aid in neuromuscular control. Essentially, the US images are being used as a source of biofeedback. This has been coined Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging (RUSI). Additional uses have emerged in recent years including Diagnostic US imaging which is the diagnosis and monitoring of pathology; and interventional US imaging which is using the US images to guide percutaneous procedures involving dry or wet needling. These three categories are performed during clinical care and fall under the umbrella term “point of care ultrasound.” The last category of US imaging use in physical therapy is paired with performing research.

In this article, some thoughts and areas for improvement were brought to light regarding each type of US imaging as well as the scope of practice and training for each type of US use. It was mentioned that RUSI sits almost entirely within the scope of the physical therapy profession, however, it can be difficult for therapists to receive training for this use. Therapists interested in learning diagnostic or interventional US imaging have more options for training because these uses of US have established criteria for training, competence, and regulation outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO), as well as oversight from the World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. These programs often are intended for other healthcare practitioners (radiologists, and sonographers), but physical therapists are able to take the courses. However, it was stated that both diagnostic and interventional US imaging do not fall within the scope of practice for a majority of physical therapists around the world. So, although training may be more available for these types of US use; therapists taking these courses gain increased experience with non-physical therapy applications, and therefore are at risk for operating outside the scope of their practice.

The authors continued with distinct recommendations for needed training for the four different types of US imaging. Several of the listed skills were fundamental knowledge that a therapist should obtain before utilizing any of the four types of US into their practice such as basic physics for US, terminology, safety, among other knowledge. Then there were skills that were specific to the particular type of US being performed. Since point-of-care use of US is generally not included as part of entry level physical therapy education programs, this knowledge needs to be obtained in a postgraduate education format. For therapists who wish to learn diagnostic application of US imaging, there are multiple courses available from schools that train sonographers. However, according to this article, the form of US imaging that sits more within the scope of practice for physical therapists, rehabilitative ultrasound imaging, does not have as many educational opportunities as diagnostic US imaging does.

Herman & Wallace offers a course that provides fundamental skills of US imaging (such as history, and knowledge of the physics needed for US imaging), as well as specific skills for real-time ultrasound imaging. The schedule of the course includes a lot of lab time with multiple US units available so the ratio of participant to US unit low. You will leave the course being able to interpret US images and use it as an assessment tool or biofeedback tool for the patient. Using RUSI will change how you treat patients! The Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging course is offered three more times this year. Join me in Columbia, MO this August; Madison, WI in September; or Chicago, IL in December to learn how to use this form of ultrasound imaging in your clinical practice!

Whittaker J, Ellis R, Hodges P, et al. Imaging with ultrasound in physical therapy: what is the PT’s scope of practice a competency-based educational model and training recommendations. Br. J Sports Med. Apr. 2019; 0:1-7.

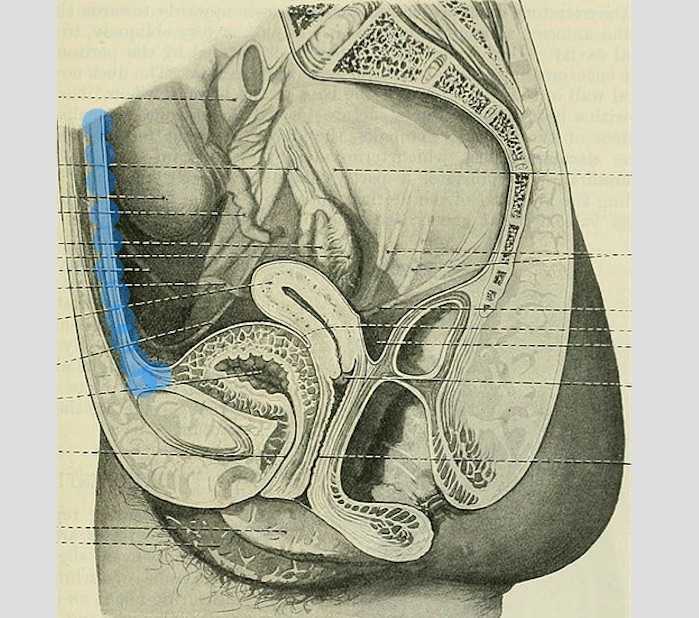

“However, at present we are all aglow with views on visceral anatomy and medical colleges are wisely establishing chairs in this department which will result in much advancement.” -Fred Byron Robinson, 1891 (Cysts of the Urachus)

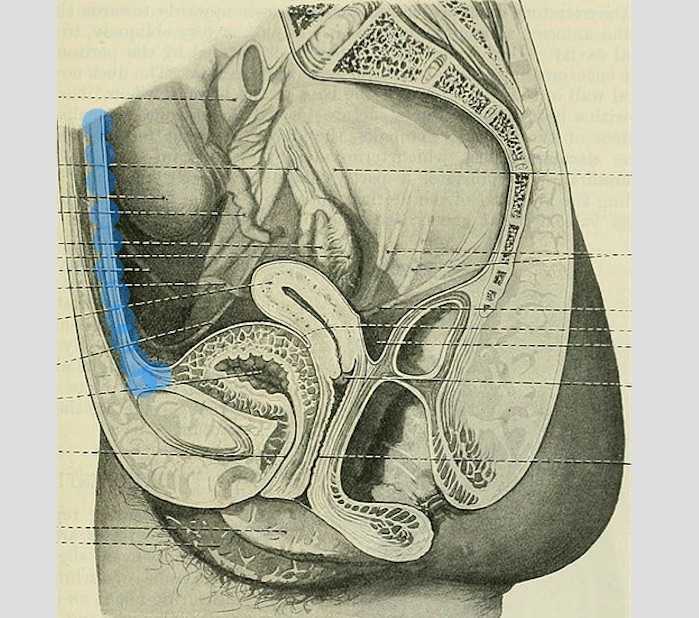

The above (fabulous) quote reminds us that many came before us who were equally excited by the study of anatomy. One anatomical structure that I know never appeared in my graduate anatomy courses is the urachus. The urachus is a structure that extends from the urinary bladder to the umbilicus (highlighted blue in the image). When investigating literature about this structure I was impressed to find publications about the urachus dating from the late 19th century.

It wasn’t until several years into my career as a physical therapist that I learned about the urachus, a structure attached to the bladder, and learned how this structure could create some rather dramatic symptoms when in dysfunction. I met a woman who was in her early 30’s and who had 6 months prior undergone a laparoscopic surgery with access just below the umbilicus. She presented to rehabilitation after seeing an urologist for severe pain that occurred towards the end of voiding. The pain was absent at any other time, but was so severe towards the latter half of emptying her bladder that she would double over in pain and “nearly pass out.” Investigation revealed a healthy, well-functioning pelvic floor and abdominal wall, but a reproduction of her severe pain with palpation to the midline between the umbilicus and the pubic bone. After grabbing some anatomy texts, I supposed that the urachus, having potentially been irritated by the laparoscopic approach, might experience a tensioning of the irritated tissue as the bladder contracted to empty. This theory appeared to hold some weight, as applying gentle manual therapy to the tissues, and teaching the patient some self-release techniques allowed her to resolve her symptoms entirely after 1-2 visits.

The urachus is formed in early development from the pre-peritoneal layer, and is described as vestigial tissue. It extends from the anterior dome of the bladder to the umbilicus, varying in length from 3-10 cm, with a diameter of 8-10 mm. There are 3 layers: an inner layer of transitional or cuboid epithelial cells surrounded by a layer of connective tissue. The remains of the urachus form the middle umbilical ligament which is a fibromuscular cord. A layer of smooth muscle that is continuous with the detrusor (smooth muscle of the bladder) makes up the outer layer. This continuity of tissue may help explain some of the clinical connections we see in patient symptoms. In the past year, I have met several patients for whom the urachus is the only tissue that reproduced their symptoms. I examined a male patient who reported urethral burning that occurred with both reset and activity. Unable to produce symptoms in any other location of the thoracolumbar spine, pelvic floor and walls, or abdomen, I palpated this structure to find that it reproduced the urethral burning. Another patient presented with a keloid c-section scar. She also described a sharp pain when the bladder was full. Treatment directed to the scar and along the midline resolved this pain, again with a couple sessions.

If you are interested in learning more about distinct anatomical connections that can help you explain (and treat) issues your patients present with, come and learn with us at the 3-day Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction, and Treatment course offered four times over the 2019 and 2020 calendars. The role of the urachus in abdominopelvic dysfunction is just one of the many topics we explore. With lectures on sexual health, pelvic pain, prostate and urinary dysfunction, there is a broad range of topics and skills to offer for clinicians who are new to men’s heath and those who have been treating for years.

Begg, R. C. (1930). The Urachus: its Anatomy, Histology and Development. Journal of Anatomy, 64(Pt 2), 170–183.

Gray, H. (1918). Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Sterling, J. A., & Goldsmith, R. (1953). Lesions of Urachus which Appear in the Adult. Annals of Surgery, 137(1), 120–128.

Leg length discrepancy (LLD) is when there is a noticeable difference in length of one leg to the other. LLD is common and can be found in 70% of the population (Gurney, 2002). LLD can be structural or functional. Structural LLD is when a long bone in the leg is longer or shorter than the other. Structural LLD is often the result of congenital or boney damage of epiphyseal plate. Functional is when there is an apparent LLD from higher in the chain such as scoliosis. Generally as pelvic floor therapists we are orthopedic based therapists. In physical therapy school we learned that a leg length discrepancy had to be >1 cm to be considered significant, and based off of recent research that is still the case. Research in the last few years has focused on whether LLD has an effect on age related changes with osteoarthritis, posture & gait, and pain. Physiopedia suggests differential diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction, scoliosis, low back pain, iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome, stress fractures, and pronation. It can often feel like a chicken or egg question.

In the clinic I typically screen for a leg length discrepancy during my initial evaluation. A LLD may be noticed upon observation of gait assessment, standing posture, or part of the pelvic obliquity screen in standing and then in supine.

In the clinic I typically screen for a leg length discrepancy during my initial evaluation. A LLD may be noticed upon observation of gait assessment, standing posture, or part of the pelvic obliquity screen in standing and then in supine.

During gait, a LLD will create bilaterteral gait impairments. Khamis et al did a systematic review of LLD and gait deviations in 2017. They narrowed the search down to 12 articles and found that LLD >1cm was significantly related to gait deviations. These deviations occurred bilaterally, and while initially compensations occurred in the sagittal plane, as the LLD increased so did the gait deviations, and then affected frontal planes of motion as well. Resende et al (2016) agrees that even mild LLD should not be overlooked. They found that the most likely gait deviations were also in the sagittal planes and consisted of rearfoot and ankle dorsiflexion and inversion, knee flexion and adduction, hip adduction and flexion, and pelvic trendelenburg.

The sagittal, or right/left plane, and frontal, or front/back, plane involvement is consistent with the differential diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction, low back pain, and pronation. Really, one could justify why a LLD could contribute to pain and dysfunction in most of the lower body. It is reasonable to think that these compensational moments in gait over a long period create boney changes in the lower extremities which may contribute to low back pain.

Clinically, a leg length discrepancy can be assessed directly with a tape measure or indirectly with a shoe lift. Badii (2014) found a higher interrater reliability with the indirect method of a shoe lift as opposed to measuring with a tape measure.

Rannisto et al (2019) looked at leg length discrepancy among meat cutters with low back pain. All participants had been working for 10 years and were greater than 35 years old. Participants needed to have a LLD of 5mm (5mm is 0.5 cm) or more and complain of low back pain of >2/10 on visual analog scale (VAS). They were all given insoles and randomized into 2 groups; the intervention group were given lifts to correct the LLD about 70%; for example a 10mm LLD was corrected to 3 mm. The LLD was measured with a laser ultrasound technique. Participants were followed for 12 months. The intervention group had improvement in low back pain intensity, sciatica intensity, and took less sick time. Possibly the most amazing part is that for those that wore the heel lift at work the compliance was good.

Leg length discrepancy can often be an underlying component contributing to complaints of pain and dysfunction. It may have more of an effect on the populations who stand or walk for most of their work, and I wonder as more people transition to standing desks if we will see more people come into the clinic with a previously undiagnosed LLD.

My biggest clinical pearls from this research is that:

- Heel lifts can be used to diagnose and then for treatment (yay! One less step of getting the tape measure out)

- The heel lift does not have to be perfect. Clinically, I will try a lift and have the person walk, and then we can make a team decision if this lift is enough and feels better

- The gait compensations are consistently adduction and internal rotation throughout the lower body chain. I will continue to work on the opposing muscle groups; lateral rotators, hip extensors and abductors.

Leg Length Discrepancy can be evaluated using various assessments. To learn orthopedic evaluative techniques for patients, consider joining Lila Abbate in her course Advanced Orthopedic Assessment for the Pelvic Health Therapist.

Maziar Badii, A Nicole Wade, David R Collins, Savvakis Nicolaou, B Jacek Kobza, Jacek A Kopec, Comparison of lifts versus tape measure in determining leg length discrepancy; Journal of Rheumatology 2014, 41 (8): 1689-94

Renan A. Resende, Renata N. Kirkwood, Kevin J. Deluzio, Silvia Cabral, Sérgio T. Fonseca. "Biomechanical strategies implemented to compensate for mild leg length discrepancy during gait" Gait & Posture, Volume 46, 2016; 147-153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.03.012

Sam Khamis, Eli Carmeli, Relationship and significance of gait deviations associated with limb length discrepancy: A systematic review, Gait & Posture, Volume 57, 2017, 115-123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.05.028

Burke Gurney, Leg length discrepancy, Gait & Posture, Volume 15, Issue 2, 2002, Pages 195-206, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00148-5.

Satu Rannisto, Annaleena Okuloff, Jukka Uitti, et al. Correction of leg-length discrepancy among meat cutters with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2019;(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2478-3.

In the United States, estimated direct medical costs for outpatient visits for chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is more than $2.8 billion per year.1 In a 2017 study in the Clinical Journal of Pain by Sanses et al, a detailed musculoskeletal exam of clients with CPP can assist both physicians as well as physical therapists in differential diagnosis and appropriate referrals for this population.

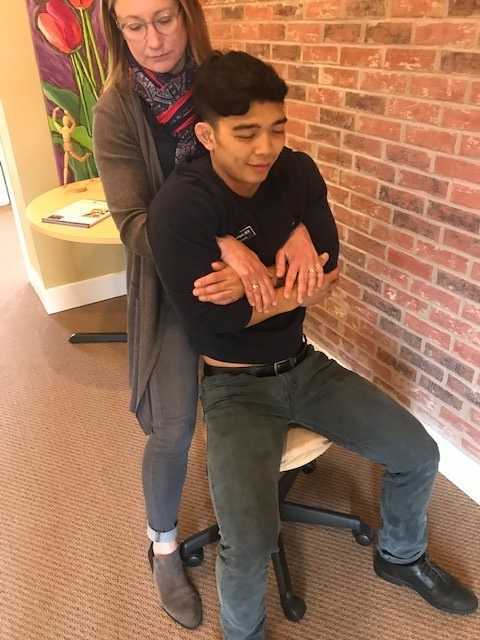

Evaluating a client with pelvic pain requires a skill set that includes direct pelvic floor as well as musculoskeletal test item clusters. The prioritization of which depends upon many factors including clinician discipline, experience, specialty vs. general setting, as well as client history, presentation and goals. In addition to the direct pelvic floor assessment, there are additional key musculoskeletal screening tests that are an essential part of a pelvic pain assessment. New this year, my course Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain will incorporate the use of Real Time Ultrasound in neuromuscular assessment and re-education of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall during the Sunday morning lab session.

Peery et al (2012) noted that abdominal pain was one of the most common presenting reasons for an outpatient physician visit in the United States. Abdominal pain is one of the many complaints that our clients may report requiring differential diagnosis including urogynecologic, colorectal, musculoskeletal, visceral or neurogenic causes. Lower abdominal quadrant pain may denote serious emergent pathology. Clinical findings, physical exam and client symptoms in addition to smart differential diagnosis must be used to determine if the abdominal pain is musculoskeletal in nature. Direct access requires physical therapists to perform a skilled initial screening for abdominal pain in order to determine if it is abdominal wall versus a visceral origin. Physicians are fluent in ruling out emergent pathology but may not be familiar with musculoskeletal tests for non-emergent pathology. Assessment of bowel and bladder function and habits are essential to perform. This blog specifically addresses three physical exam tests that can be performed as part of abdominal wall pain screening. According to Cartwright et al, the location of the abdominal pain should drive the evaluation.

Carnett’s test is a simple clinical test that assesses abdominal pain response when a client tenses their abdominal muscles. A positive Carnett’s sign denotes the origin of symptoms within the abdominal wall with a negative tests suggesting intra-abdominal pathology. The test is performed in supine, the clinician gently palpating the area of abdominal pain and has the client lift their head and shoulders off the table. Conditions such as myofascial trigger points, scar and muscular pain would be flared with palpation of the contractile tissue with activation of the abdominal wall muscles. If the pain is due to visceral origin, appendicitis for example, the pain would remain unchanged with palpation with head lift. Although some perform Carnett’s test by lifting both legs off the table, this method may cause unnecessary pain in clients with poor lumbopelvic control. (Figure 1) The head and shoulder lift option is felt to be comparable method of performing Carnett’s test.

Blumberg’s sign is most commonly used to rule in appendicitis, peritonitis or a visceral driver of right lower quadrant pain. The test is performed by the clinician applying deep pressure over McBurney’s point (Figure 2) with an abrupt and rapid release of pressure. Although there are anatomical variations in appendix location, pain reproduction is consistent with a positive test and immediate referral to the ER is indicated.

Thoracic dysfunction, including disc herniation, can result in abdominal pain.2 In thoracic discogenic driven abdominal pain, symptoms would likely be exacerbated by coughing, sneezing, spinal flexion and activities that would increase spinal loading. A simple screening for this is seated thoracic traction. If the client reports reduction or resolution of symptoms with traction, further musculoskeletal tests including regional movement and PIVM testing could be implemented to rule in or rule out need for diagnostic imaging.

In the Herman Wallace course “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain” participants learn a comprehensive musculoskeletal screen including abdominal, neural mobility and conductivity, pelvic ring, pelvic floor and biomechanical contributing factors to pelvic pain. Evidence based test item clusters are defined, along with their diagnostic accuracy, for all associated systems in order to outline a comprehensive screen for pelvic pain clients. To learn more about musculoskeletal screening for pelvic pain, check out faculty member Elizabeth Hampton PT, DPT, WCS, PRPC, BCB-PMD’s course Finding the Driver of Pelvic Pain, which is next offered Jun 28, 2019 - Jun 30, 2019 in Columbus, Ohio. We are fortunate to have Dick Poore, President of The Prometheus Group present on Sunday June 30th for technical support for the Real Time Ultrasound portion of the course.

1. Sanses et al. "The Pelvis and Beyond: Musculoskeletal Tender Points in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain". Clin. J. Pain. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000307

2. Papadakos et al. "Thoracic Disc Prolapse Presenting with Abdominal Pain: Case Report and Review of the Literature". Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 20019 Jul. doi: 10.1308/147870809X401038

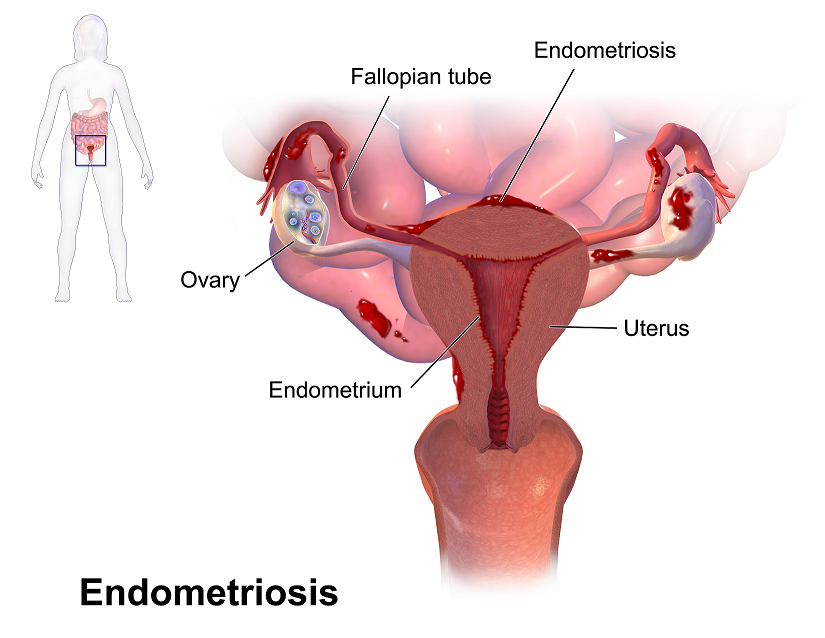

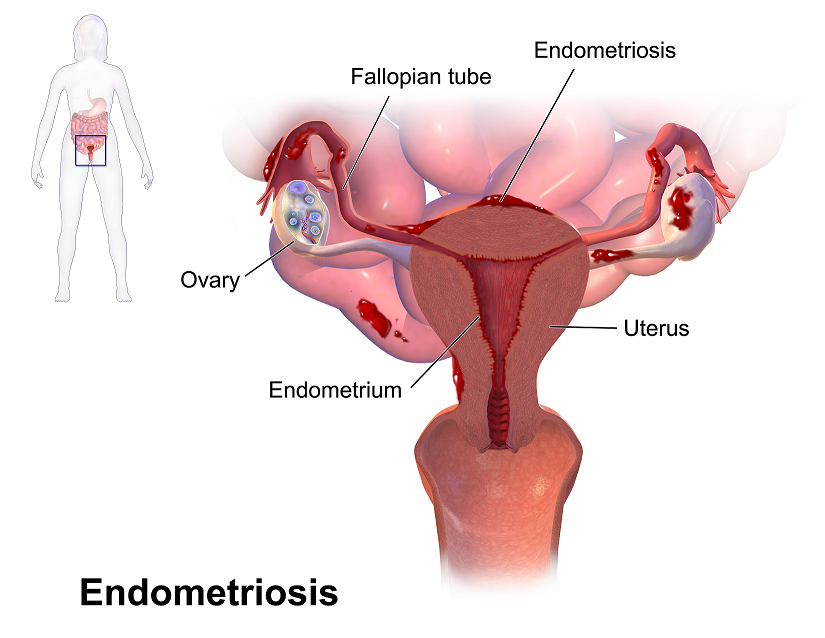

Recent data suggests that there are about 4 million American women diagnosed with endometriosis, but that 6/10 are not diagnosed. Currently, using the gold standard for diagnosis there are potentially 6 million American woman that may experience the sequelae of endometriosis without having appropriate management or understanding the cause of their symptoms.

The gold standard for endometriosis is laparoscopy either with or without histologic verification of endometrial tissue outside of the uterus. However, there is a poor correlation between disease severity and symptoms. The Agarwal et al study suggests a shift to focus on the patient rather than the lesion and that endometriosis may better be defined as “menstrual cycle dependent, chronic, inflammatory, systemic disease that commonly presents as pelvic pain”. There is often a long delay in symptom appreciation and diagnosis that can range from 4-11 years. The side effects of this delay are to the detriment of the patient; persistent symptoms and effect of quality of life, development of central sensitization, negative effects on patient-physician relationship. If this disease continues to go untreated it may affect fertility and contribute to persistent pelvic pain.

The authors suggest a clinical diagnosis with transvaginal ultrasound for patients presenting with persistent or cyclic pelvic pain, patient history, have symptoms consistent with endometriosis, or other findings suggestive of endometriosis. The intention of using transvaginal ultrasound is to make diagnosis more accessible and limit under diagnosis. It is not intended to minimize laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool or treatment option.

The authors suggest a clinical diagnosis with transvaginal ultrasound for patients presenting with persistent or cyclic pelvic pain, patient history, have symptoms consistent with endometriosis, or other findings suggestive of endometriosis. The intention of using transvaginal ultrasound is to make diagnosis more accessible and limit under diagnosis. It is not intended to minimize laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool or treatment option.

The algorithm for a clinical diagnosis evaluates patient presentation of the following:

- Symptoms including persistent or cyclic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea or painful menstruation cramps, deep dyspareunia or pain with deep vaginal penetration, cyclic dyschezia or straining for soft stools, cyclic dysuria or pain with urination, cyclic catamenial symptoms located in other systems such as acne or vomiting.

- Assessment of patient history including infertility, current chronic pelvic pain, or painful periods as an adolescent, previous laparoscopy with diagnosis, painful periods that are not responsive to NSAIDS, and a family history.

- Physical exam physicians assess for nodules in cul de sac, retroverted uterus, mass consistent with endometriosis, visible or obvious external endometrioma. Imaging should be ordered or performed.

- Clinical signs would consist of endometrioma with US, presence of soft markers (sliding sign) this is where the fundus of the uterus is compared to its neighboring structures and can indicate the immobility of those structures, and nodules or masses.

Of course, there are differential diagnosis for endometriosis, and those are symptoms of non-cyclical patterns of pain and bladder/bowel dysfunction that would indicate IBS, UTI, IC/PBS. A history of post-operative nerve entrapment of adhesions. Examination positive for pelvic floor spasm, severe allodynia in vulva and pelvic floor, masses such as fibroids. It is important to note that these other diagnoses can coexist with endometriosis and do not rule out possible endometriosis diagnosis.

Hopefully, diagnosing individuals earlier and possibly at a younger age would limit the disease severity and symptoms. This would allow this population to limit the possibility of central sensitization and pain persistence that can affect so much of daily life. Earlier diagnosis may affect infertility and allow this population to make informed decisions about family and career from a place of empowerment.

Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, Laufer MR, Leyland N, Missmer SA,Singh SS, Taylor HS, "Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action", American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2019), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.039.

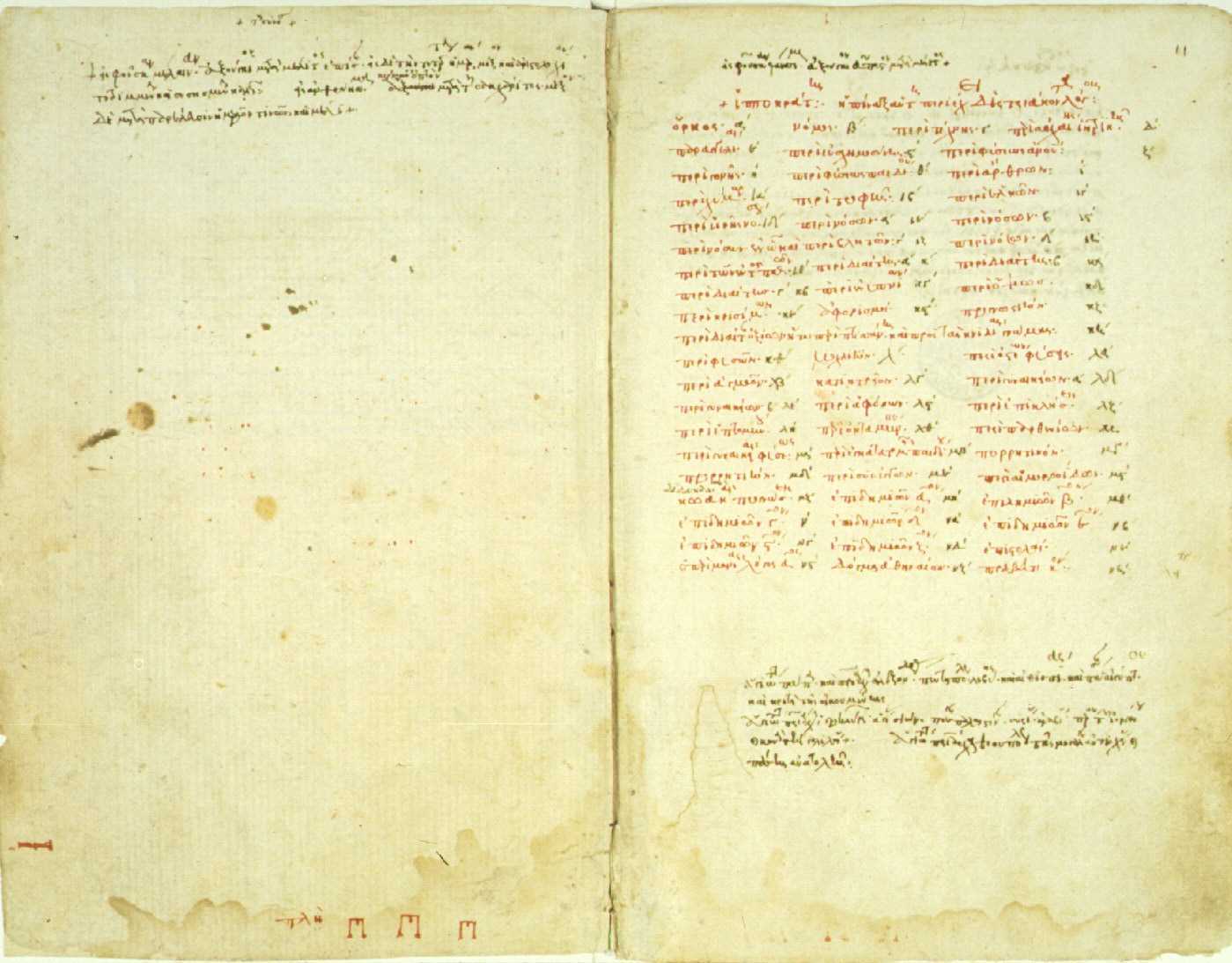

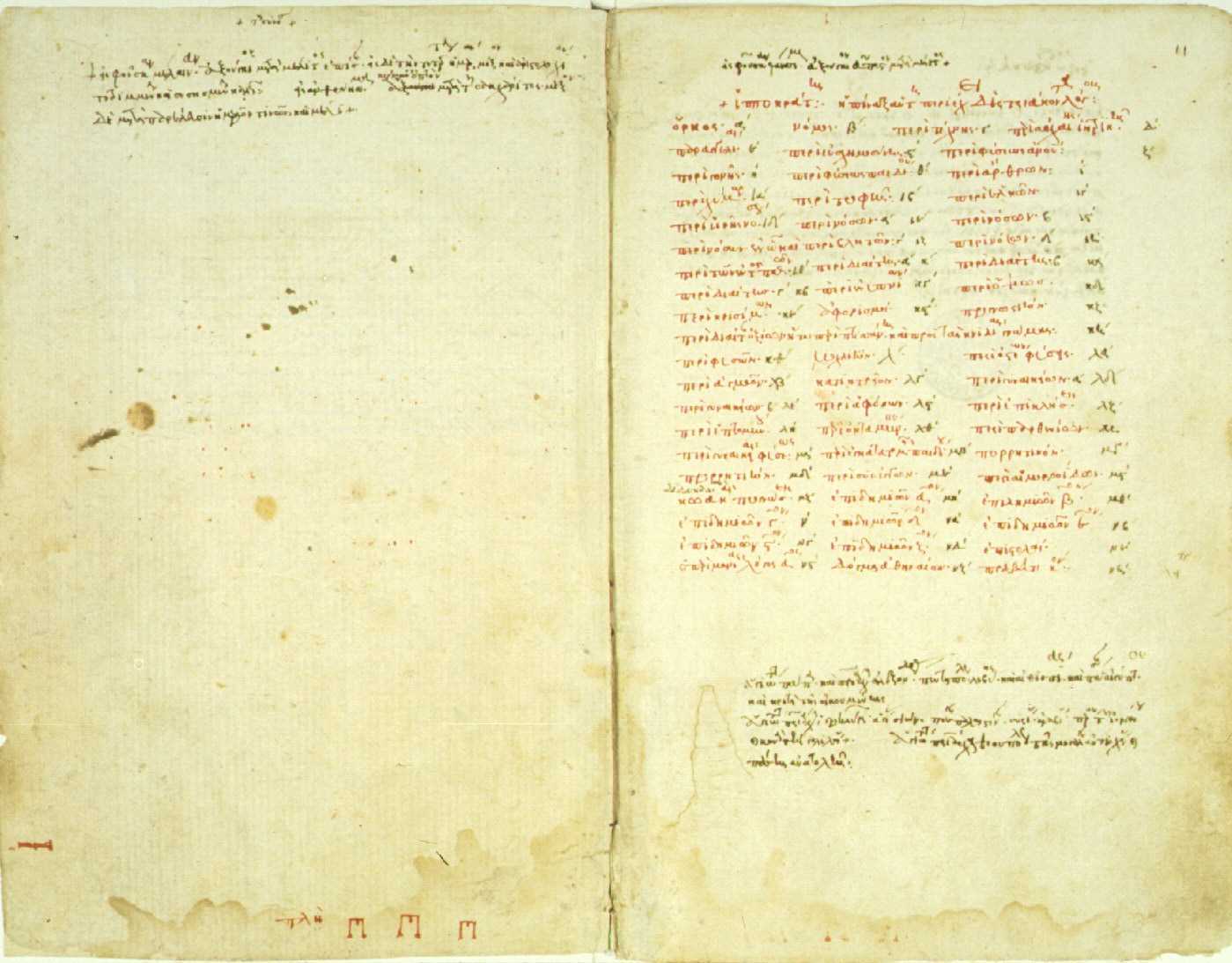

The need for artful incorporation of Hippocrates’ wisdom is great in today’s healthcare landscape. As conversation of nutrition broadens into multidisciplinary fields, his wisdom resonates: first, “we must make a habit of two things; to help; or at least to do no harm”. Second, we must modernize the ancient adage: “let food be thy medicine and let medicine be thy food”. And finally, health care providers will do well to be guided by his insight that “all disease starts in the gut”. Hippocrates’ keen observations during his era, modern science is confirming, hold keys to the plight of our times as we seek to find better ways to manage complex conditions commonly encountered in pelvic rehab practice settings and beyond.

Considered some of the oldest writings on medicine, the “Hippocratic Corpus” is a collection of more than 60 medical books attributed directly and indirectly to Hippocrates himself who lived from approximately 460 to 377 BCE.2 According to the Corpus, Hippocratic approach recommends physical exercise and a “healthy diet” as a remedy for most ailments - with plants being prized for their healing properties. If -during illness states - employment of nourishment and movement strategies fail, then medicinal considerations could be made. This logos - the ancient Greek word for logic - is the art of reason whose relevance today is perhaps more poignant than in ancient times.

Considered some of the oldest writings on medicine, the “Hippocratic Corpus” is a collection of more than 60 medical books attributed directly and indirectly to Hippocrates himself who lived from approximately 460 to 377 BCE.2 According to the Corpus, Hippocratic approach recommends physical exercise and a “healthy diet” as a remedy for most ailments - with plants being prized for their healing properties. If -during illness states - employment of nourishment and movement strategies fail, then medicinal considerations could be made. This logos - the ancient Greek word for logic - is the art of reason whose relevance today is perhaps more poignant than in ancient times.

In this logos, by making a habit of helping, or at the very least, not harming, it becomes particularly important to identify the unique nutritional landscape that surrounds us. The Hippocratic Oath emanates reason. It is logical that we would seek to practice (healthcare) to the best of our ability, share knowledge with other providers, employ sympathy, compassion and understanding, and help in disease prevention whenever possible.2 One of the most helpful and powerful aspects of rehabilitation is the gift of time we have for meaningful and instructional conversation with our clients. Our interactions with clients can and should address the realm of nutrition as it relates to the health of the mind and body. Because, after all - to help - is why many become health care providers in the first place.

Detailing a “healthy diet” in Hippocratic times was certainly simpler, as the uncontrolled variable of processed foods- as we know them- did not exist. Therefore, we reflect upon the quote: “let food be thy medicine and let medicine be thy food” and acknowledge that this modern food landscape is vastly different 1 than in ancient times. Compounding the issue, our standard logic for helping has gotten somewhat out of order. And both medicine and food carry meanings today reflective of modern times. The issues of poly-pharmacy and the tragedy of medically prescribed unintentional overdoses (or intolerances) remind us of our ‘medicine first’ mentality and the unfortunate reality that medicine is not the cure-all we so wish it could be. Further, not all ‘food’ today is food. Real food sustains and nourishes us. Real food can also heal. We need to celebrate real food for being real food, and champion it’s miraculous ability to support, heal, and transform the human condition.

Finally, health care providers will do well to be guided by Hippocratic insight that “all disease starts in the gut” and to logically extrapolate the opposite: much healing can begin in the gut. It is through this ancient concept that we can organize our modern science and begin to concretely and intentionally help heal ourselves and others from the inside out. Once we understand the key role of digestion and our gut on our health and well-being, the rest is pure logic. We simply need a map for navigation of these universal concepts to go along with our renewed appreciation for the art of reason.

Let Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist help provide this map. Evolve your nutritional logos into a beautiful and nourishing framework by joining the hundreds of pelvic rehab therapists and other health care providers who have attended Nutrition Perspectives in Pelvic Rehab. Be inspired and empowered on your integrative journey. Live courses will be offered at three sites in 2019: March 1-3 in Arlington, VA, June 7-9 in Houston, TX, and October 11-13 in Tampa, FL!

Fardet, A., Rock, E., Bassama, J., Bohuon, P., Prabhasankar, P., Monteiro, C., . . . Achir, N. (2015). Current food classifications in epidemiological studies do not enable solid nutritional recommendations for preventing diet-related chronic diseases: the impact of food processing. Adv Nutr, 6(6), 629-638. doi:10.3945/an.115.008789

Biography.com https://www.biography.com/people/hippocrates-082216. Accessed January 11, 2019.

Faiq Shaikh, M.D. is a dual fellowship-trained nuclear medicine physician & Informaticist, with a focus on translational research in the domains of Cancer imaging, Radiomics, Genomics, Informatics and Machine learning applications in Medicine. He has written more than 35 scientific articles and abstracts and 3 book chapters on related topics.

Introduction

Pelvic floor weakening is a common (occuring in half of women 50+) condition that leads to descent of the urinary bladder, uterovaginal vault, and rectum in the females, leading to urinary and fecal incontinence, and in extreme cases, pelvic organ prolapse.

Causes

Pelvic floor weakness is caused by a variety of factors, most of which increase the intra-abdominal pressure, such as pregnancy, multiparity, advanced age, menopause, obesity, connective tissue disorders, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc. All these conditions lead to weakness of the pelvic musculature, ligaments, and fascia support result in descent of the pelvic floor organs.

Anatomy

The pelvic floor is divided into three compartments:

- Anterior compartment: contains the urinary bladder and urethra

- Middle compartment: contains the uterus, cervix, and vagina

- Posterior compartment: contains the rectum.

The structures in these compartments are supported by muscles, fascia, and ligaments anchoring them to the bony pelvis.

The endopelvic fascia is the most superior layer and covers the levator ani muscles and the pelvic viscera. Laterally, it forms the arcus tendineus. It attaches the cervix and vagina to the pelvic side wall as the parametrium and paracolpium. Posteriorly, the endopelvic fascia forms the rectovaginal fascia between the posterior vaginal wall and the rectum.

These fascial condensations are not well visualized on conventional MRI but their defects may be seen indirectly through secondary findings. These ligaments are not visualized on conventional MRI but may be visualized with an endovaginal coil which allows higher resolution and signal-to-noise ratio.

The levator ani muscles lie deep in relation to the endopelvic fascia and comprise of the puborectalis and the iliococcygeus muscles. Posteriorly and in the midline, the iliococcygeus condenses to form the levator plate. These are all well visualized on MRI. The perineal membrane lies inferior to the levator ani muscles and separates the vagina and rectum, which may be damaged during vaginal delivery when episiotomy is performed.

Pathophysiology

Pelvic floor relaxation is the weakness of the supporting muscles, fascia, and ligaments. This weakness progresses with age and may be related to hypoestrogenic states, such as menopause.

- occurs when the urinary bladder prolapses into the anterior vaginal wall, which may cause urinary incontinence.

- occurs due to weakness of the rectovaginal fascia, prolapsing rectum into the posterior vaginal wall, which may cause fecal incontinence.

- The parametrium and paracolpium weakness causes prolapse of the cervix and uterus.

- occurs when the small bowel prolapses through the rectovaginal fascia.

Accurate assessment of all compartments of the pelvic floor is necessary for surgical planning in order to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Diagnostics

Methods for the assessment of pelvic floor weakness include urodynamics, voiding cystourethrography, ultrasonography of the bladder neck and anal sphincter, fluoroscopic cystocolpodefecography, and MRI - which m is now the standard-of-care for preoperative planning for pelvic floor dysfunction, although it’s still not used for routine assessment.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI visualizes all three compartments of the pelvic floor and the pelvic support muscles and organs. We perform dynamic MRI of the pelvic floor with the patient in the supine or lateral decubitus positions. Conversely, MRI defecography or fluoroscopic cystocolpodefecography are performed in the sitting position, which is closer to the physiologic state. MR defecography is not superior to dynamic supine MRI for depiction of clinically relevant bladder descent and rectoceles. Overall, MRI accurately detects enteroceles and its contents when compared with fluoroscopic cystodefecography.

The preferred MRI pelvis protocols include: Ultrafast, large-field-of-view, T2-weighted sequences such as single-shot fast spin-echo (SSFSE), and half-Fourier acquisition turbo spin-echo (HASTE). After the dynamic examination is completed, small-field-of-view (20–24 cm) T2-weighted axial fast spin-echo (FSE) or axial turbo spin-echo (TSE) sequences are acquired to obtain high-resolution images of the muscles and fascia of the pelvic floor. The entire examination is typically completed in 20 minutes. This exam is performed with a torso phased-array coil wrapped around the pelvis. Endovaginal coil may be used to improve the spatial resolution of the pelvic ligaments, but it is invasive and can be uncomfortable.

MRI visualizes the uterus, cervix, and rectovaginal space. Ultrasonic gel may be administered into the vagina and rectum for better visualization. Also, incompletely voiding the urinary bladder improves visualization of the bladder and anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

For patients with a rectocele, patient is imaged after having evacuated the rectal contents. Chronic constipation and perineal hernias show as ballooning of the iliococcygeus muscle. The level of the pelvic floor is demarcated radiologically on the midsagittal image using the pubococcygeal line (from the most inferior portion of the pubic symphysis to the last horizontal sacrococcygeal joint). The levator plate should be parallel to the pubococcygeal line in normal cases.

The H line (5 cm) extends from the inferior symphysis pubis to the posterior anorectal junction on the midsagittal image and depicts the levator hiatus. The M line (2 cm) goes perpendicular from the pubococcygeal line to the most distal aspect of the H line and depicts the descent of the levator hiatus from the pubococcygeal line. Pelvic floor prolapse causes sloping of the levator plate and increasing length of the H and M lines, indicating widening and descent of the levator hiatus.

The T2-weighted axial images of the pelvic floor should be analyzed for signal intensity, symmetry, thickness, and fraying of the pelvic floor muscles. Bladder neck at strain should be less than 1 cm away from the pubococcygeal line. Descent of the bladder neck below the pubococcygeal line depicts the prolapse of the urinary bladder through the anterior vaginal wall resulting in a cystocele. Descent of the bladder neck during strain results in clockwise rotational descent of the bladder neck and proximal urethra. Distortion of the periurethral and paraurethral ligaments is seen in stress urinary incontinence. The normal butterfly shape of the vagina may also be altered by weakening of the paravaginal ligaments as it is displaced posteriorly. Prolapse of the middle compartment is associated with the vaginal apical prolapse and damage to the paracolpium seen in post-hysterectomy patients. On midsagittal MR images, descent of the uterus, cervix and vagina usually suggests disruption of the uterosacral or cardinal ligaments and elongated H and M lines. Pelvic organ prolapse increases the urogenital hiatus in the levator muscles. Caudal angle of more than 10° between the levator plate and the pubococcygeal line on midsagittal image is a sign of pelvic floor weakness.

On the midsagittal image, rectocele is identified by a rectal bulge of more than 3 cm (from anal canal and the tip of the rectocele). Contrast-enhanced MR shows hyperintense T2 signal in peritoneal fat contents in peritoneoceles, the hyperintense fluid-filled small-bowel loops in enteroceles, and the hyperintense gel-filled rectum/sigmoid colon in rectoceles/sigmoidoceles. Intussusception of the rectum on MR is seen as rectum invaginating distally toward the anal canal (MR defecography is superior to dynamic supine MR for this indication).

Performing MRI for pelvic floor dysfunction when indicated for surgical planning and the assessment if the extent of disease may reduce the risk of surgical failure.

This information is extremely useful to urogynecologists and surgeons.

MRI of pelvic floor dysfunction: review. Law YM, Fielding JR. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008.

Authors: Tamara Rial, PhD, CSPS, Kathleen Doyle-Elmer, PT, DPT and Rebecca Keller, PT, MSPT, PRPC

Tamara Rial, PhD, CSPS, co-founder and developer of Low Pressure Fitness will be presenting the first edition of Low Pressure Fitness and Abdominal Massage for Pelvic Floor Care Level 2 and 3 in Princeton, New Jersey in September, 2019. Rebecca Keller and Kathleen Doyle-Elmer are certified Low-Pressure Fitness specialists with training in rehabilitative ultrasound imaging. In this article, the authors discuss and explore the use of transabdominal ultrasound during Low Pressure Fitness on the abdominal and pelvic floor structures.

Real-time ultrasound imaging is a reliable and valid method to evaluate muscle structure, activity and mobility. Over the past few years, there has been increasing interest in the use of transabdominal ultrasound in the field of rehabilitation. The additional value of ultrasound imaging is that it allows for real-time analysis and visual feedback during the performance of pelvic floor and abdominal exercises (Hides et al., 1998). In the field of pelvic health, this is of notable importance when assessing proper movement of the deep abdominal and pelvic muscles during voluntary muscle actions. Transabdominal ultrasound has been found to be a safe, noninvasive, and accurate method to assess and observe muscular and fascial activity (Khorasani et al., 2012). When therapists learn how to properly use and apply ultrasound imaging, this technique can be a comprehensive tool for the clinician and a comfortable procedure for the patient. Moreover, it may be the method of choice for some patients who don’t want to have an internal pelvic examination (Van Delft, Thakar & Sultan, 2015). In this regard, a cross-sectional study found a moderate-to-strong correlation between ultrasound measurements and both digital examination and perineometry for the assessment of pelvic floor muscle actions (Volløyhaug et al., 2016).

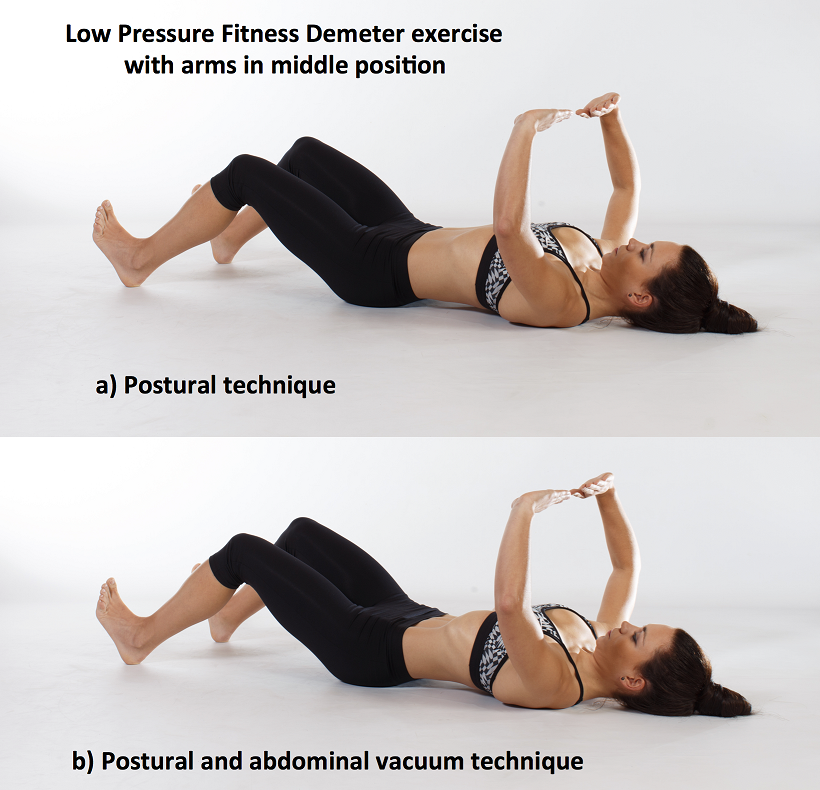

Recently, Low Pressure Fitness has gained popularity as a pelvic floor training program aimed at reducing pressure on the pelvic structures while engaging the stabilizing muscles through postural and breathing exercises. In order to evaluate proper execution of Low-Pressure Fitness exercises as well as abdomino-pelvic muscle function during this type of training, real-time transabdominal ultrasound can be a clinically relevant tool.

Sagittal and Transverse Pelvic Floor/Urinary Bladder Assessment

The amount of movement of the bladder base on transabdominal ultrasound is considered an indicator of pelvic floor muscle mobility during pelvic floor muscle exercises (Khorasani et al., 2012). When properly executed, the Low-Pressure Fitness technique will allow the bladder to lift and the pelvic floor muscles to contract. These observed actions can be cued and progressed due to the real-time imaging biofeedback of the ultrasound. Because of the postural activation and diaphragm lift occurring during Low Pressure Fitness, the bladder fascial support system is tensioned resulting in a desirable bladder lift.

For example, we used a Pathway® Musculoskeletal Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging unit with a curvilinear transducer and Prometheus Pathway® rehabilitative ultrasound software utilizing the pre-set parameters (Abdominal Wall 7.5MHz and Bladder 5.0MHz) during a Low-Pressure Fitness basic supine posture. A standardized bladder filling protocol was used before imaging to ensure sufficient bladder filling to allow clear imaging of the base of the bladder and pelvic floor muscles.

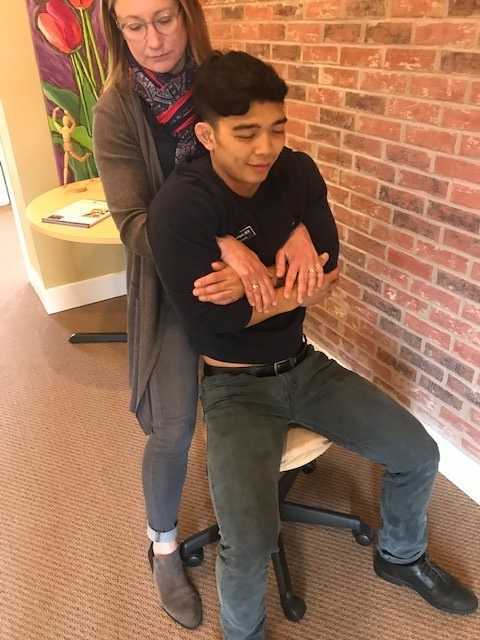

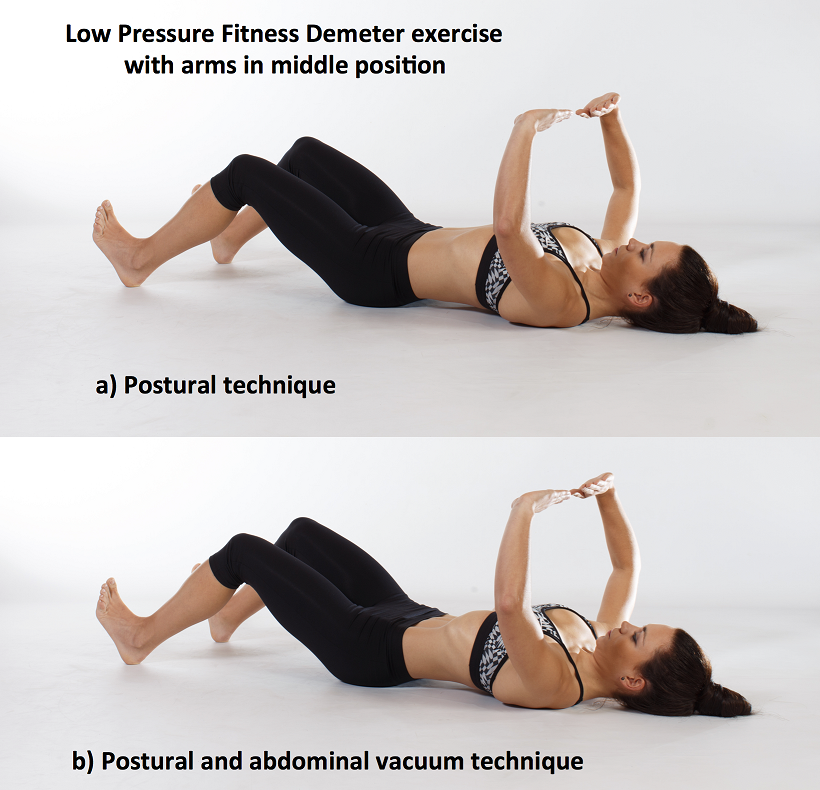

For the transverse view, radiologic standards were used, and the ultrasound transducer was placed in the transverse plane suprapubically and angled in a caudal/ posterior direction to obtain a clear image of the inferior-posterior aspect of the bladder. The participant was asked to perform the Low-Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise in the supine position with a neutral pelvis and knees flexed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Demeter exercise with postural technique and with postural and abdominal vacuum technique combined.

The following video illustrates the pelvic floor/urinary bladder during: a) resting position; b) active pelvic floor contraction; c) Low Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise and; d) Low Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise combined with a voluntary pelvic floor muscle contraction. It is noticeable a greater bladder lift and pelvic floor activation with the postural and breathing cueing added to an active pelvic floor contraction than with the pelvic floor contraction alone.

Video of the behavior of the pelvic floor muscles in a sagital and transversal view during the supine position of Low Pressure Fitness and with the combination of an active pelvic floor muscle contraction.

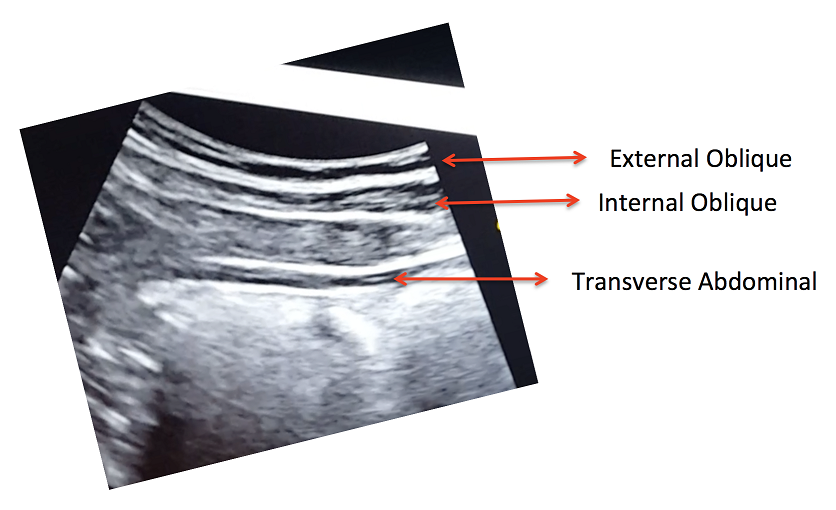

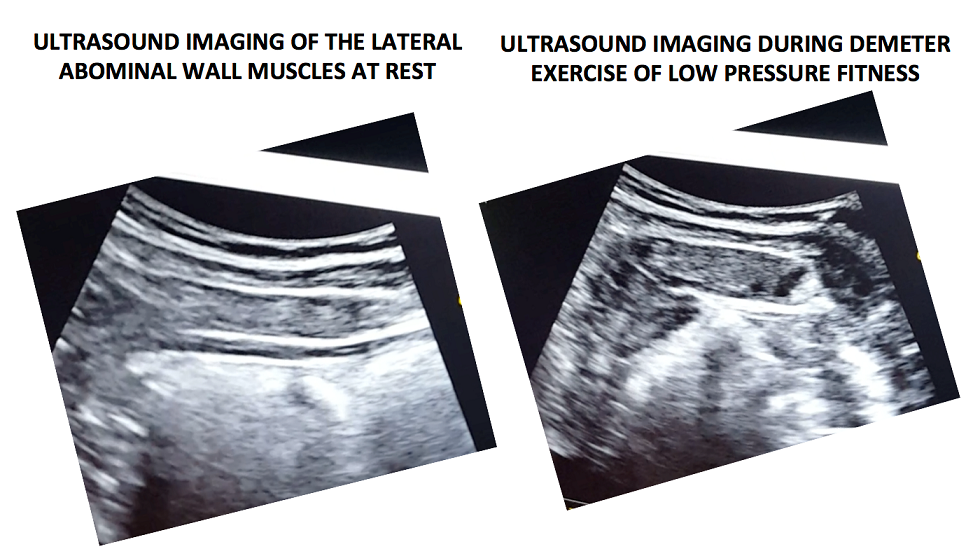

Lateral Abdominal Wall Assessment

The lateral abdominal muscle ultrasound assessment allows us to observe the structural changes produced in the transversal section of the abdominal muscles in the midpoint between the anterior iliac crest and the costal angle. At low levels of contraction, the extent of transverse abdominis thickening measured using ultrasound is reported to be a valid method of assessment compared with either fine wire electromyographic measures of transverse activity (McMeeken et al., 2004). It is well established in the scientific literature that the lateral abdominal muscles provide stability to the trunk in different functional activities. Therefore, the assessment of the size, thickness and sliding of the abdominal wall is important for patients who present with lumbo-pelvic and/or pelvic floor dysfunctions. In this regard, patients with low back pain show different abdominal wall muscle activation patterns (i.e. less slide of the abdominal fascia and muscle thickness) than those without low back pain (Gildea et al., 2014; Unsgaard-Tondel et al., 2012).

Figure 2 shows the three muscle layers of the lateral wall in the resting position. The superficial layer corresponds to the external oblique, the middle layer to the internal oblique and the deep layer to the transverse abdominal muscle.

Figure 2. View of the right lateral abdominal wall at rest.

A key breathing component of the Low-Pressure Fitness program is the abdominal vacuum which manipulates intra-abdominal, intra-thoracic and intra-pelvic pressures during the breath-holding phase. Another key aspect of Low-Pressure Fitness is the shoulder girdle activation, spine elongation and ankle-dorsiflexion (Rial & Pinsach, 2017). Of note, previous studies have demonstrated greater transverse abdominis activation when performing ankle dorsi-flexion (Chon et al., 2010). We used transabdominal ultrasound to assess the lateral abdominal wall response during ankle dorsiflexion, shoulder girdle activation and the abdominal vacuum during Low Pressure Fitness.

In the following video, a voluntary (active) abdominal contraction is performed in order to distinguish this action from the involuntary abdominal contractions during Low Pressure Fitness. Afterwards, the postural technique of ankle dorsiflexion and shoulder girdle activation are performed in the Demeter exercise with arms in middle position (Figure 1). Lastly, an abdominal vacuum maneuver is added to the postural technique. If the exercises are properly executed, the progressive sliding and thickness of the abdominal muscles throughout exercise sequence should be observable (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Ultrasound imaging at rest and during the complete LPF technique.

Video of a voluntary (active) abdominal contraction or draw-in maneuver is performed in order to distinguish this action from the involuntary abdominal contractions that occur during Low Pressure Fitness in a supine position

Muscle thickness of the transverse and internal oblique as well as a noticeable slide of the anterior abdominal fascia are observable during the Demeter exercise of Low-Pressure Fitness. This exercise pattern reflects an abdominal draw-in maneuver and a “corseting effect”. In this regard, notice the lateral pull or displacement of the edge of the anterior fascial insertion of the transverse the internal oblique muscle.

Navarro et al., (2017) used transabdominal ultrasound to assess the muscular responses of the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles in a group of women who underwent pelvic physiotherapy over two months. They found a significant increase in the transversal section of the transverse abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles when compared to resting in the supine position. Similar to the position assessed by Navarro et al. (2017), we also assessed the pelvic floor and abdominal muscle responses during a Low-Pressure Fitness supine exercise.

Transabdominal ultrasound can provide a noninvasive and informative visual biofeedback when training patients with Low Pressure Fitness. This ultrasound imaging can be a valuable tool to both the client and the clinician to objectify progress, assist with validating correct Low-Pressure Fitness form with positioning and vacuum/hypopressive maneuver as well as a motivational technique for the client. As demonstrated during our rehabilitative ultrasound imaging, observable bladder lift, pelvic floor activation and desirable lateral abdominal muscular corseting (slide and thicking) occurs during Low Pressure Fitness postural exercises and breathing. Since Low Pressure Fitness is a progressive exercise program, qualified instruction, technique driven progression and understanding pelvic floor health are needed to optimize patient outcomes.

Chon SC, Chang KY, You JS. Effect of the abdominal draw-in manoeuvre in combination with ankle dorsiflexion in strengthening the transverse abdominal muscle in healthy young adults: a preliminary, randomised, controlled study. Physiotherapy 96: 130-6, 2017.

Gildea JE, Hides JA, Hodges PW. Morphology of the abdominal muscles in ballet dancers with and without low back pain: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Sci Med Sport. 17(5): 452-6, 2014.

Khorasani B, Arab AM, Sedighi Gilani MA, Samadi V, Assadi H. Transabdominal ultrasound measurement of pelvic floor muscle mobility in men with and without chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology, 80: 673-7, 2012.

McMeeken JM, Beith ID, Newham DJ, Milligan P, Critchley DJ. The relationship between EMG and change in thickness of transversus abdominis. Clin Biomech 19: 337–342, 2004.

Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Use of real-time ultrasound imaging for feedback in rehabilitation. Man Ther. 3:125-131,1998.

Navarro B, Torres M, Arranz B, Sanchez O. Muscle response during a hypopressive exercise after pelvic floor physiotherapy: Assessment with transabdominal ultrasound. Fisioterapia 39: 187-94, 2017.

Rial T, Pinsach P. Practical Manual Low Pressure Fitness Level 1. International Hypopressive & Physical Therapy Institute, Vigo, 2017.

Unsgaard-Tøndel M, Lund Nilsen TI, Magnussen J, Vasseljen O. Is activation of transversus abdominis and obliquus internus abdominis associated with long-term changes in chronic low back pain? A prospective study with 1-year follow-up. Br J Sports Med, 46(10): 729-34, 2012.

Van Delft K, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Pelvic floor muscle contractility: digital assessment vs transperineal ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 45: 217-22, 2015. Volløyhaug I, Mørkved S, Salvesen Ø, Salvesen KÅ. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle contraction with palpation, perineometry and transperineal ultrasound: a cross-sectional study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 47: 768-73, 2016.