A couple of years ago, I wrote a blog about an interesting article by Hides and Stanton that related size and strength of the multifidus to the risk for lower extremity injury in Australian professional football players.

Now some of the same researchers are looking above. A prospective cohort study has recently been published that examined factors and their effects on concussions. Physical measurements of risk factors were taken in pre-season among Australian football players. These measurements included balance, vestibular function, and spinal control. To measure these outcomes the following tests were included: for balance the amount of sway across six test conditions were performed; vestibular function was tested with assessments of ocular-motor and vestibular ocular reflex; and for spinal control cervical joint position error, multifidus size, and contraction ability was tested. The objective measure was concussion injury obtained during the season diagnosed by the medical staff.

Now some of the same researchers are looking above. A prospective cohort study has recently been published that examined factors and their effects on concussions. Physical measurements of risk factors were taken in pre-season among Australian football players. These measurements included balance, vestibular function, and spinal control. To measure these outcomes the following tests were included: for balance the amount of sway across six test conditions were performed; vestibular function was tested with assessments of ocular-motor and vestibular ocular reflex; and for spinal control cervical joint position error, multifidus size, and contraction ability was tested. The objective measure was concussion injury obtained during the season diagnosed by the medical staff.

The findings were so interesting! Age, height, weight, and number of years playing football were not associated with concussion. Cross-sectional area of the multifidus at L5 was 10% smaller in players who went on to sustain a concussion compared to players that did not receive a concussion. There were no significant differences observed between the players that received concussion and those who did not with respect to the other physical measures that were obtained.

With all the recent evidence about the harmful effects of concussions amongst our athletes, I find this information amazing and am excited to see where the researchers take this in the future. The next question for the physical therapist is how do we train the multifidus? The multifidus can be difficult to retrain in some individuals. It is a hard muscle for some patients to learn to recruit. Biofeedback using ultrasound imaging can make this daunting task easier for many patients. With the cost of ultrasound units coming down, it is also a very reasonable tool for clinics to look at investing in.

Join me to learn more about the multifidus and how to use ultrasound imaging in the retraining process. Future course offerings include August in New Jersey, and November in San Diego. I look forward to seeing you there!

Hides, Stanton. Can motor control training lower the risk of injury for professional football players? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014; 46(4): 762-8.

Leung, Hides, Franettovich Smith, et al. Spinal control is related to concussion in professional footballers. Brit J of Sports Med. 2017; 51(11).

When I mentioned to a patient I was writing a blog on yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), she poured out her story to me. Her ex-husband had been abusive, first verbally and emotionally, and then came the day he shook her. Violently. She considered taking her own life in the dark days that followed. Yoga, particularly the meditation aspect, as well as other counseling, brought her to a better place over time. Decades later, she is happily married and has practiced yoga faithfully ever since. Sometimes a therapy’s anecdotal evidence is so powerful academic research is merely icing on the cake.

This study by Walker and Pacik (2017) included 3 voluntary participants: a 75 and a 72 year old male veteran and a 57 year old female veteran, all whom were experiencing a varying cluster of PTSD symptoms for longer than 6 months. Pre- and post-course scores were evaluated from the PTSD Checklist (a 20-item self-reported checklist), the Military Version (PCL-M). All the participants reported decreased symptoms of PTSD after the 5 day training course. The PCL-M scores were reduced in all 3 participants, particularly in the avoidance and increased arousal categories. Even the participant with the most severe symptoms showed impressive improvement. These authors concluded Sudarshan Kriya (SKY) seemed to decrease the symptoms of PTSD in 3 military veterans.

Cushing et al., (2018) recently published online a study testing the impact of yoga on post-9/11 veterans diagnosed with PTSD. The participants were >18 years old and scored at least 30 on the PTSD Checklist-Military version (PCL-M). They participated in weekly 60-minute yoga sessions for 6 weeks including Vinyasa-style yoga and a trauma-sensitive, military-culture based approach taught by a yoga instructor and post-9/11 veteran. Pre- and post-intervention scores were obtained by 18 veterans. Their PTSD symptoms decreased, and statistical and clinical improvements in the PCL-M scores were noted. They also had improved mindfulness scores and decreased insomnia, depression, and anxiety. The authors concluded a trauma-sensitive yoga intervention may be effective for veterans with PTSD symptoms.

Domestic violence, sexual assault, and unimaginable military experiences can all result in PTSD. People in our profession and even more likely, the patients we treat, may live with these horrors in the deepest recesses of their minds. Yoga is gaining acceptance as an adjunctive therapy to improving the symptoms of PTSD. The Trauma Awareness for the Physical Therapist course may assist in shedding light on a dark subject.

Walker, J., & Pacik, D. (2017). Controlled Rhythmic Yogic Breathing as Complementary Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Military Veterans: A Case Series. Medical Acupuncture, 29(4), 232–238.

Cushing, RE, Braun, KL, Alden C-Iayt, SW, Katz ,AR. (2018). Military-Tailored Yoga for Veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Military Medicine. doi:org/10.1093/milmed/usx071

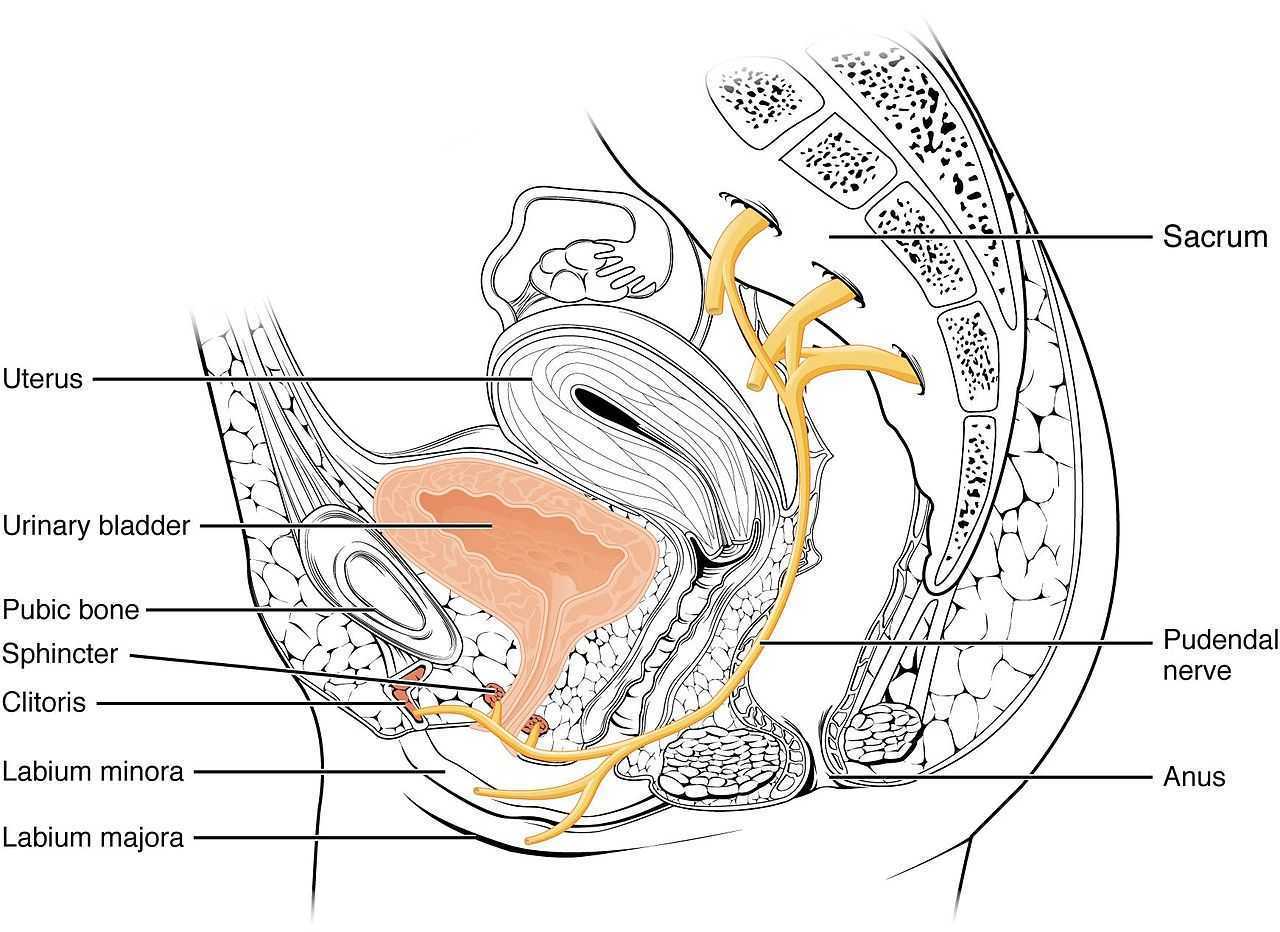

Recently, I had a patient present to my practice with unretractable vaginal pain that was causing her quite a bit of suffering. Peyton (name changed) had been referred by a local osteopathic physician. For around a year, she had increasing severe vaginal pain. There was no history of assault, trauma, fall, or injury around the time of onset of symptoms. However, she had a kidney infection that caused back pain in the month prior to her pain onset.

Peyton is home schooled, but she was unable to attend outings that required longer sitting, such as field trips or church. She also was having some urinary retention with start and stop stream and resultant urinary frequency. Peyton’s mother said the pain was distressing to Peyton and would cause her to cry. She had an unremarkable medical history. However, under further questioning, we discovered she did have a history of bed wetting later than usual (until age 7) and she had persistent leg pain. With standing longer than 15 minutes, her legs would hurt and feel weak, which prevented her from performing sports or being physically active. She also had experienced some achy low back sensations since the kidney infection. Peyton had been screened by urology, her primary care, an osteopath, as well as a vulvar pains specialist who diagnosed her with nerve pain, but said there is no good viable treatment.

Peyton is home schooled, but she was unable to attend outings that required longer sitting, such as field trips or church. She also was having some urinary retention with start and stop stream and resultant urinary frequency. Peyton’s mother said the pain was distressing to Peyton and would cause her to cry. She had an unremarkable medical history. However, under further questioning, we discovered she did have a history of bed wetting later than usual (until age 7) and she had persistent leg pain. With standing longer than 15 minutes, her legs would hurt and feel weak, which prevented her from performing sports or being physically active. She also had experienced some achy low back sensations since the kidney infection. Peyton had been screened by urology, her primary care, an osteopath, as well as a vulvar pains specialist who diagnosed her with nerve pain, but said there is no good viable treatment.

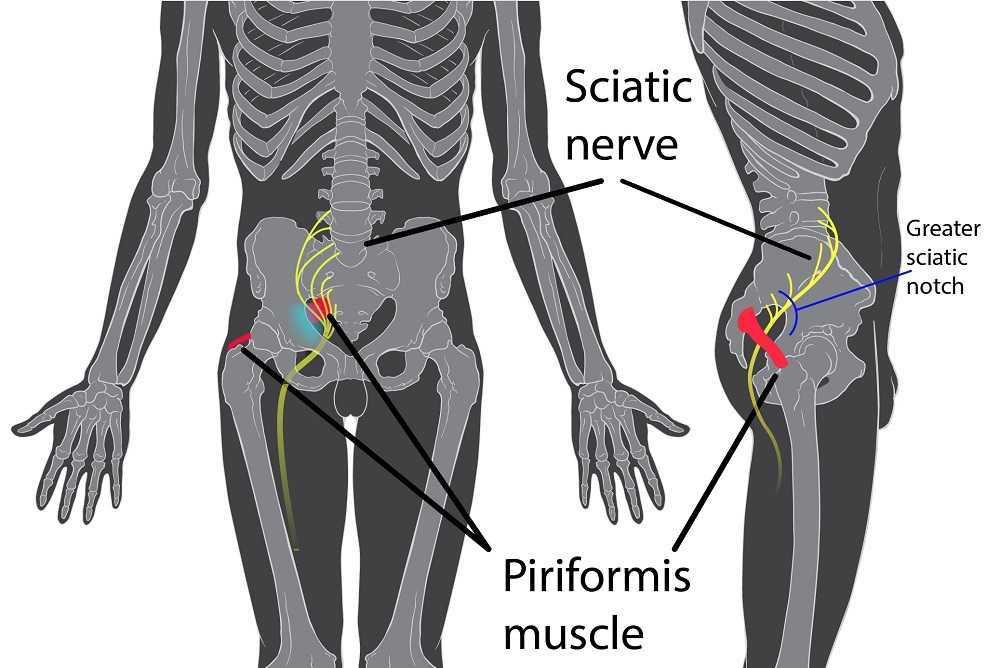

Objective findings revealed normal range of motion in her spine with the exception of limited forward flexion (feeling of back tightness at end range). Hip screening was negative for FABERS, labral screening or capsular pain patterns. General dural tension screening was positive for increased lower extremity and sensation of back tightness with slump c sit. Neural tension test was positive bilaterally for sciatic, R genitofemoral, L Iliohypogastric and Ilioinguinal nerves, and bilateral femoral nerves. Patient had a mild, barely perceptible lumbar scoliosis, and development of bilateral lower extremities and feet was symmetric and normal.

Because of the child’s age, we did not perform internal vaginal exam or treatment. This required treating the nerves that supply the vaginal area. All treatments were done with the patient’s mother present with both consent of the child and the mother.

For treatment, we started with the three inguinal nerves (Ilioinguinal, Iliohypogastric and genitofemoral) because of their relationship with the kidney (symptoms came on after kidney infection) as well as the correlation with the patient’s most limiting symptoms (genital pain). We cleared the fascia along the lumbar nerve roots, the lateral trunk fascia, the psoas, the inguinal region, the entrapments along the kidney and psoas, the inguinal rings and canal, and worked on neural rhythm (these techniques can be learned at the Pelvic Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment class that I will be teaching later this month).

Over the next weeks, we used similar treatments for the sciatic nerve, femoral nerve, pudendal, and coccygeal nerves. We noted that the patient had an area of restricted tissue along her coccyx that was adhered, and her symptoms had some correlation with tethered cord. We did lots of soft tissue work along the coccyx and working along the coccyx roots, including some internal rectal work. We also did fascial and visceral work in the bladder region, as well as in the lumbar and sacro-coccygeal region.

Peyton’s referring physician and mother were notified of findings and possible tethered cord symptoms (leg weakness and pain, bladder symptoms, delayed nocturnal continence). The patient’s family felt she was getting better and was not interested in any kind of surgical intervention, and her physician also felt that with our progress, he was not interested in exploring that referral, unless the family was interested.

After just 4 treatments Peyton was no longer having any vaginal symptoms and was emptying the bladder normally. After 8 treatments Peyton was reporting no more lumbar pain or lower extremity symptoms, and follow up treatments were reduced to once a month. The patient was given a home program of neural flossing in a small yoga program we recorded on her mother’s phone. We had her mother work on the small area that remained adhered along patient’s tailbone. The area is much smaller, but it reproduces some pelvic pain for the patient, so we are carefully and slowly working along this area because of some of the global neural sx it produces.

The patient’s mother reports she is more active, no longer complaining of leg or vaginal pain. The patient has less generalized anxiety and she is able to void fully. When the pt grows in height, there is a return in some symptoms, likely due to increased neural tension. So, we have the family on standby and when the patient grows, they come back in for 2 visits, which is usually enough to get the patient back to her new baseline.

My 6 year old girl (going on 13) asks “Alexa” to play the Descendants II soundtrack over and over again. So the song, “Space Between,” was lingering in my head while reading the most recent articles on pudendal neuralgia, particularly when pudendal entrapment is to blame. After all, entrapment, by medical standards, describes a peripheral nerve basically being caught in between two surrounding anatomical structures.

Ploteau et al., (2016) presented 2 case studies highlighting the warning signs when pudendal nerve entrapment does not follow the Nantes criteria. A brief summary of those 5 criteria follows:

Ploteau et al., (2016) presented 2 case studies highlighting the warning signs when pudendal nerve entrapment does not follow the Nantes criteria. A brief summary of those 5 criteria follows:

- Pain in the region of the pudendal nerve innervation from anus to penis or clitoris.

- Pain most predominant while sitting.

- The patient does not wake at night from the pain.

- No sensory impairment can be objectively identified.

- Diagnostic pudendal nerve block relieves the pain.

The case studies of a 31 and a 68 year old female revealed endometrial stromal sarcoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma in the ischiorectal fossa, with night pain was noted in both patients, as well as no pain with sitting or defecation, respectively. Clinicians must always be mindful to resolve red flags in patients.

In 2016, Florian-Rodriguez, et al., studied cadavers to determine the nerves associated with the sacrospinous ligament, focusing on the inferior gluteal nerve. Fourteen cadavers were observed, noting the distance from various nerves to the sacrospinous ligament (from a pelvic approach) and to the ischial spine (from a gluteal approach). The S3 nerve was closest to the sacrospinous ligament, and the pudendal nerve was the closest to the ischial spine. In 85% of subjects, 1 to 3 branches from S3/S4 nerves pierced or ran anterior to the sacrotuberous ligament and pierced the inferior part of the gluteus maximus muscle. The authors concluded the inferior gluteal nerve was less likely to be the source of postoperative gluteal pain after sacrospinous ligament fixation; however, as the pudendal nerve branches from S2-4, it was more likely to be implicated in postoperative gluteal pain.

A study by Ploteau et al. (2017) explored the anatomical position of the pudendal nerve in people with pudendal neuralgia. In 100 patients who met the Nantes criteria, 145 pudendal nerves were surgically decompressed via a transgluteal approach. At least one segment of the pudendal nerve was compressed in 95 of the patients, either in the infrapiriform foramen, ischial spine, or Alcock’s canal. In 74% of patients, nerve entrapment was between the sacrospinous ligament and the sacrotuberous ligament. Anatomical variants were found in 13% of patients, often with a transligamentous course of the nerve.

When the pudendal nerve is caught in the narrow space between ligaments in the pelvis, diagnosing the source of pain is paramount. Research supports a gluteal approach in releasing the entrapped nerve. Post-surgical care falls into the hands of pelvic floor therapists, so taking “Pudendal Neuralgia and Nerve Entrapment: Evaluation and Treatment” may be something to consider in order to provide optimal care.

Ploteau, S, Cardaillac, C, Perrouin-Verbe, MA, Riant, T, Labat, JJ. (2016). Pudendal Neuralgia Due to Pudendal Nerve Entrapment: Warning Signs Observed in Two Cases and Review of the Literature. Pain Physician. 19(3):E449-54

Florian-Rodriguez, ME, Hare, A, Chin, K, Phelan, JN, Ripperda, CM, Corton, MM. (2016). Inferior gluteal and other nerves associated with sacrospinous ligament: a cadaver study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 215(5):646.e1-646.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.025

Ploteau, S, Perrouin-Verbe, MA, Labat, JJ, Riant, T, Levesque, A, Robert, R. (2017). Anatomical Variants of the Pudendal Nerve Observed during a Transgluteal Surgical Approach in a Population of Patients with Pudendal Neuralgia. Pain Physician. 20(1):E137-E143

Tiffany Ellsworth Lee MA, OTR, BCB-PMD joined the Herman & Wallace faculty to teach a course on biofeedback along with Jane Kaufman, PT, M.Ed, BCB-PMD. The month of April is Occupational Therapy month, and we are celebrating by highlighting the role that Occupational Therapists play in pelvic floor rehabilitation. Tiffany founded a biofeedback program at Central Texas Medical Center in San Marcos in 2004, and currently runs her a pelvic rehab private practice .

Working in this area of biofeedback is extremely rewarding and fulfilling to help change peoples’ lives. I have a private practice now exclusively dedicated to treating patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. I became involved in working with patients with incontinence and pelvic floor disorders because of many opportunities along my career path. I have been an Occupational Therapist since 1994. Both of my parents are also OTs, so I think I was born to do this!

Working in this area of biofeedback is extremely rewarding and fulfilling to help change peoples’ lives. I have a private practice now exclusively dedicated to treating patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. I became involved in working with patients with incontinence and pelvic floor disorders because of many opportunities along my career path. I have been an Occupational Therapist since 1994. Both of my parents are also OTs, so I think I was born to do this!

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC wrote a blog recently about the role of OTs in pelvic health. She writes:

“As we look closer at the framework and the definition of OT (Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, 3rd edition 2014), there is clear evidence that the occupational therapist (OT) has a role in the treatment of pelvic health conditions. Importantly, occupations are defined by this document as ‘…various kinds of life activities in which individuals, groups, or populations engage, including activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), rest and sleep, education, work, play, leisure, and social participation.”

The clearest examples of the OT’s role in pelvic health occupations within this section include:

- ADL section: toileting and hygiene (continence needs, intentional control of bowel movements and urination) and sexual activity.

- IADLs section: sleep participation (sustaining sleep without disruption, performing nighttime care of toileting needs).

- Achieving full participation in work, play, leisure, and social activities, requires one to be able to maintain continence in a socially acceptable manner in which they can feel confident and comfortable to fulfill their roles and duties.

"We believe that the great patient need that exists can be better served by having trained OTs able to treat pelvic health conditions"

How to get started as an OT

Occupational therapists wishing to pursue pelvic floor have a few options. The first thing is to find a pelvic floor clinical setting or work with their respective settings to check to see if they can start a women's health program with a strong focus on pelvic floor. OTs quite often do not start out in pelvic health directly after school and since this is a newer area as compared to other certifications such as the NDT and PNF it takes a little bit of research, time and effort to find one’s exact niche. To get started, an OT should seek out courses that teach the basics of bladder and bowel management. It is important to understand the anatomy and physiology of the bladder, bowel, and sexual systems.

Incontinence and pelvic floor disorders have a profound impact on occupation, the daily activities that give life meaning! OTs should have a larger role in treating this patient population. Offering hope to our patients is imperative when he/she is dealing with pelvic floor dysfunction!

Keep an eye out for an upcoming post from Tiffany with some inspiring clinical case studies. You can join Tiffany and Jane Kaufman in Biofeedback for Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction to get lots of hands-on time with surface eletromyography, and to work toward BCIA certification!

Neurophysiology is a dynamic and highly complex system of neurological connections and interactions that allow for bodily performance. When all of those connections are working correctly, our bodies can function at optimal levels. When there is a break or injury to those connections, dysfunction results but amazingly in some circumstances, our bodies have work arounds to allow for certain functions to continue working.

If we take the sexual neural control system of the male, for instance, a perfect example of this can be described. Many men were injured fighting in World War II. During their time in battle, many experienced spinal cord injuries. Some of these injuries were severe resulting in complete spinal cord damage at level of injury. A physician, Herbert Talbot, in 1949, documented his examination of 200 men with paraplegia. Two thirds of the men were surprisingly able to achieve erections and some were able to experience vaginal penetration and orgasm. Much of their basic functionality had been lost however amazingly there was preservation of erectile function.

The reason these men with paraplegia were able to maintain erectile or orgasm functionality is due to the physiological function in the sacral spinal cord. A reflex arc is present in this region. The definition of a reflex arc is a nerve pathway that has a reflexive action involving sensory input from a peripheral somatic or autonomic nerve synapsing to a relay neuron or interneuron in the sacral cord segment then synapsing to a motor nerve for output to the muscular region. These messages do not need to travel up the spinal cord to the brain in order to be activated. Instead they work within a ‘loop’ at the sacral spinal cord level. In the case of spinal cord injury, erectile function as well as other functions controlled by reflex arcs, can be preserved.

For women, the same is true. In order for a female to have engorgement of the clitoris or orgasm, the sacral spinal reflex arc needs to be intact. If a woman experiences a spinal cord injury above the sacral region, the ability to have a reflexive orgasm within the sacral spinal reflex arc will remain.

The sacral reflex arc also plays an important role in activation of the pelvic floor muscles during the sexual response cycle. During genital stimulation in both the male and female, the bulbospongiosus or bulbocavernosus begins to activate in a reflexive pattern to hinder the outflow of blood from the region which facilitates erectile tissue of the penis and clitoris to become erect. This can then be followed by rhythmic reflexive contractions of the pelvic floor musculature during orgasm.

To learn more about the implications that neurologic disorders can have on the sexual system, please join us for Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab, coming to Grand Rapids, MI in September.

Goldstein, I. (2000). Male sexual circuitry. Scientific American, 283(2), 70-75.

Sipski, M. L. (2001). Sexual response in women with spinal cord injury: neurologic pathways and recommendations for the use of electrical stimulation. The journal of spinal cord medicine, 24(3), 155-158.

Wald, A. (2012). Neuromuscular Physiology of the Pelvic Floor. In Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract (Fifth Edition)(pp. 1023-1040).

In the dim and distant past, before I specialised in pelvic rehab, I worked in sports medicine and orthopaedics. Like all good therapists, I was taught to screen for cauda equina issues – I would ask a blanket question ‘Any problems with your bladder or bowel?’ whilst silently praying ‘Please say no so we don’t have to talk about it…’ Fast forward twenty years and now, of course, it is pretty much all I talk about!

But what about the crossover between sports medicine and pelvic health? The issues around continence and prolapse in athletes is finally starting to get the attention it deserves – we know female athletes, even elite nulliparous athletes, have pelvic floor dysfunction, particularly stress incontinence. We are also starting to recognise the issues postnatal athletes face in returning to their previous level of sporting participation. We have seen the changing terminology around the Female Athlete Triad, as it morphed to the Female Athlete Tetrad and eventually to RED S (Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome) and an overdue acknowledgement by the IOC that these issues affected male athletes too. All of these issues are extensively covered in my Athlete & The Pelvic Floor’ course, which is taking place twice in 2018.

But what about pelvic pain in athletes?

How can we ensure that pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is on the radar for a differential diagnosis, or perhaps a concomitant factor, when it comes to athletes presenting with hip, pelvis or groin pain? Gluteal injuries, proximal hamstring injuries, and pelvic floor disorders have been reported in the literature among runners: with some suggestions that hip, pelvis, and/or groin injuries occur in 3.3% to 11.5% of long distance runners.

How can we ensure that pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is on the radar for a differential diagnosis, or perhaps a concomitant factor, when it comes to athletes presenting with hip, pelvis or groin pain? Gluteal injuries, proximal hamstring injuries, and pelvic floor disorders have been reported in the literature among runners: with some suggestions that hip, pelvis, and/or groin injuries occur in 3.3% to 11.5% of long distance runners.

In Podschun’s 2013 paper ‘Differential diagnosis of deep gluteal pain in a female runner with pelvic involvement: a case report’, the author explored the case of a 45-year-old female distance runner who was referred to physical therapy for proximal hamstring pain that had been present for several months. This pain limited her ability to tolerate sitting and caused her to cease running. Examination of the patient's lumbar spine, pelvis, and lower extremity led to the initial differential diagnosis of hamstring syndrome and ischiogluteal bursitis. The patient's primary symptoms improved during the initial four visits, which focused on education, pain management, trunk stabilization and gluteus maximus strengthening, however pelvic pain persisted. Further examination led to a secondary diagnosis of pelvic floor hypertonic disorder. Interventions to address the pelvic floor led to resolution of symptoms and return to running.

‘This case suggests the interdependence of lumbopelvic and lower extremity kinematics in complaints of hamstring, posterior thigh and pelvic floor disorders. This case highlights the importance of a thorough examination as well as the need to consider a regional interdependence of the pelvic floor and lower quarter when treating individuals with proximal hamstring pain.’ (Podschun 2013)

Many athletes who present with proximal hamstring tendinopathy or recurrent hamstring strains, display poor ability to control their pelvic position throughout the performance of functional movements for their sport: along with a graded eccentric programme, Sherry & Best concluded ‘…A rehabilitation program consisting of progressive agility and trunk stabilization exercises is more effective than a program emphasizing isolated hamstring stretching and strengthening in promoting return to sports and preventing injury recurrence in athletes suffering an acute hamstring strain’

If you are interested in learning more about how pelvic floor dysfunction affects both male and female athletes, including broadening your differential diagnosis skills and expanding your external treatment strategy toolbox, then consider coming along to my course ‘The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor’ in Chicago this June or Columbus, OH in October.

The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), Mountjoy et al 2014: http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/48/7/491

‘DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DEEP GLUTEAL PAIN IN A FEMALE RUNNER WITH PELVIC INVOLVEMENT: A CASE REPORT’ Podschun A et al Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013 Aug; 8(4): 462–471. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3812833/

‘A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains’ Sherry MA, Best TM J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004 Mar;34(3):116-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15089024

Sara Chan Reardon, DPT, WCS, BCB-PMD is a pelvic floor dysfunction specialist practicing in New Orleans, LA. Sara was named the 2008 Section on Women’s Health Research Scholar for her published research on pelvic floor dyssynergia related constipation. She was recognized as an Emerging Leader in 2013 by the American Physical Therapy Association. She served as Treasurer of the APTA’s Section on Women's Health and sat on their Executive Board of Directors from 2012-2015. Today she was kind enough to share a bit about her course Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation, which is taking place twice in 2018.

My name is Sara Reardon, and I teach the Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation course, which I wrote and developed in the year 2015. At the time, I had been a pelvic health Physical Therapist for over 10 years. Earlier in my career, I had taken the Pelvic Floor 2A course by Herman and Wallace Institute, which was a fantastic and thorough introduction to treating a male patient.

My name is Sara Reardon, and I teach the Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation course, which I wrote and developed in the year 2015. At the time, I had been a pelvic health Physical Therapist for over 10 years. Earlier in my career, I had taken the Pelvic Floor 2A course by Herman and Wallace Institute, which was a fantastic and thorough introduction to treating a male patient.

Over the years, I started seeing more and more men with post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction in my clinic. Urinary incontinence is the most common and costly complication in men following prostate removal surgery, and their quality of life is directly related to their duration of experiencing those symptoms. Evidence supports that pelvic floor muscle training started as soon as possible after surgery can help decrease incontinence and improve quality of life. I enjoyed being able to help men decrease their incontinence and improve their other symptoms after all they had been through following a cancer diagnosis and treatment.

No courses focused specifically on treating post-prostatectomy pelvic floor dysfunction were offered at the time, so I scoured the research, shadowed with physicians, observed surgeries, and attended urology conferences to understand how to effectively treat these individuals. Treating this population of men is fun, fulfilling, and rewarding, and I was inspired to help other pelvic health physical therapists dive deeper as I witnessed the impact pelvic health physical therapy can have on the quality of life of these patients. I love teaching this course, and I am excited to help other pelvic health professionals learn evidence based and effective treatment strategies to help these men navigate their recovery after prostatectomy.

Join Dr. Reardon in Philadelphia, PA on June 2-3, 2018 or in Houston, TX on November 10-11, 2018 to learn evaluation and treatment techniques for men recovering from prostatectomy surgery.

Angie Mueller PT, DPT is the instructor of Low Pressure Fitness and Abdominal Massage for Pelvic Floor Care, a new course on the hypopressive technique and abdominal massage for pelvic health. Join Dr. Mueller on July 27-29 in Princeton, NJ to learn more!

One of the first things I do as a pelvic PT when helping a woman recover from pelvic or core dysfunction, is center her uterus. I believe the uterus is the center of a women- biomechanically, physiologically, and energetically. I have seen that when the uterus is out of position, everything else in the pelvis and core is largely impacted and functions less efficiently. This includes muscular, gastrointentinal, liver, bowel and bladder, hormonal and sexual function.

The uterus is supported by several important ligaments, which extend from the uterus out to the pelvic bones, as well as to the organs surrounding it- bladder, bowel and intestines. So if this magnificent central organ is out of her “center”- leaning forwards or backwards, or tipped to on side or the other- this can lead to a myofascial imbalance in the pelvis and cause symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, pain, and hormonal imbalances.

The uterus is supported by several important ligaments, which extend from the uterus out to the pelvic bones, as well as to the organs surrounding it- bladder, bowel and intestines. So if this magnificent central organ is out of her “center”- leaning forwards or backwards, or tipped to on side or the other- this can lead to a myofascial imbalance in the pelvis and cause symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction, pain, and hormonal imbalances.

In treating thousands of women with pelvic dysfunction, I have observed that a uterus which is leaning too far forward (anteflexed) is often associated with urinary incontinence, issues with bladder urgency and frequency, and bladder prolapse (cystocele). A uterus that is tipped backwards is often associated with constipation, hemorrhoids and bowel prolapse (rectocele). A uterus that is leaning left or right is often associated with hip dysfunction, sacroiliac joint dysfunction and lumbo-pelvic alignment issues. This leads to and hip and/or knee and/or back pain due to asymmetrical pulling of the internal abdomino-pelvic fascia, especially the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments, which affects pelvic and sacral bone alignment, and then knee and ankle tracking. So centering the uterus will balance the internal pelvic and abdominal fascia, and can significantly improves cases of back pain, hip pain, knee or ankle pain.

Ensuring our organs are in their best position for receiving blood, lymph, nerve and hormonal support is critical to their health and function! If any organ in the body, especially the uterus, is not in its optimal position to receive blood, nerve, lymphatic and hormonal circulation, its function will be impacted. Therefore a mal-positioned uterus can also lead to problems with the menstrual cycle, painful periods, and fertility. When assisting any woman through a rehabilitative process, I have found it critical to appreciate how her uterine position contributes to and impacts her overall pelvic and core health- from a musculoskeletal, biomechanical and physiological perspective.

I have found that the best pelvic therapy outcomes result from use of both passive and active techniques to center the uterus. The first step is passive positioning of the uterus, which is most efficiently accomplished through abdominal massage. Abdominal self massage should be done daily. Abdominal massage will help to release any myofascial and ligamentous restrictions that are leading to a mal-positioned uterus. Abdominal massage also greatly improves blood flow and lymphatic circulation to the gut and pelvic organs leading to improved digestion and organ detoxification. Once her uterus is centered by the massage, it is important to immediately implement an active technique that will keep the uterus centered. This active uterine positioning technique must trigger the appropriate posture and breath that will keep her uterus centered with movement and throughout the activities of the day.

The second step to positioning her uterus is active activation of abdomino-pelvic musculature and key fascial chains that elevate and center the pelvic organs. This is accomplished through one of the latest core neuro-reeducation techniques- Low Pressure Fitness®. The Low Pressure Fitness methodology involves a seamless progression of postures and poses that cause a reduction in pressure in the abdomen and trigger an automatic response from the core muscles- abdominals, pelvic floor, multifidus, diaphragm. Low Pressure Fitness uses a breathing technique known as Hypopressive Breathing to reduce intra-abdominal pressure and optimize organ position. The term Hypopressive means “low pressure”. Traditional exercise, core training, sports, and most of our everyday activities are Hyperpressive – they increase the pressure in the abdomen. When the pressure in the abdomen is not appropriately managed, pressure increases, and this causes the spine to compress and the organs (especially the uterus) to move downward and away from their optimal “centered” position. But when the hypopressive breath is triggered, the pressure in the abdomen is reduced, the spine decompresses, the core musculature is gently strengthened, all of the organs lift, and the uterus is centered.

When the uterus is centered, magic happens… the fascial tension in the pelvis balances out; the resting tone of the abdominal and pelvic muscles improve and become easier to strengthen; the blood flow and lymphatic circulation in the pelvis is improved and sexual function and fertility is enhanced; hormones are better regulated and monthly cycles regulate; bowel and bladder function is optimized; the waistline reduces; pain in the back, abdomen and hips is reduced and posture improves. When all of these wonderful things occur, it is directly associated with improved energy, mood, creativity and self confidence. So remember, centering the uterus, through both active and passive techniques, is key when treating any woman. Self abdominal massage followed up by Low Pressure Fitness® are the most powerful techniques I have found to center the uterus and resolve pelvic and core dysfunction in women of all ages and lifestyles.

Dr. Nicole Cozean was just awarded the IC/BPS Physical Therapist of the Year by the IC Network, one of the largest patient advocacy groups for interstitial cystitis! Today she shares her treatment approach for this complex dysfunction. Join Dr. Cozean in San Diego on April 28-29, 2018 to learn everything there is to know about interstitial cystitis.

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a chronic pelvic pain condition characterized by pelvic pain and urinary urgency/frequency. IC is frequently accompanied by other symptoms1, including painful intercourse, low back or hip pain, nocturia, and suprapubic tenderness.

While pelvic floor physical therapy is the most proven treatment for interstitial cystitis, most patients require a multi-disciplinary approach for optimal results. The majority are forced to develop this holistic approach on their own, but one of the most valuable things a physical therapist can provide is assistance in creating their own unique treatment plan. The American Urological Association has released treatment guidelines for interstitial cystitis, and potential treatments fall into several different categories. It is important to note that most treatments aren’t effective for the majority of patients, so a trial-and-error approach is needed to find the right balance for each patient. Tracking symptoms with a weekly symptom log can be a powerful tool to optimize the individual treatment plan.

Summary of the AUA Guidelines for IC – Download Here

Oral Medications

Oral medications are primarily used to reduce pain.Anti-depressants can dampen the nervous system, decreasing the severity of pain reported. Anti-histamines have also been shown to be effective in reducing the pain and symptoms of interstitial cystitis, perhaps because of their ability to reduce inflammation and break the cycle of dysfunction-inflammation-pain (the DIP cycle). Some patients require opioid painkillers for adequate pain control.

Urinary tract analgesics can provide temporary pain relief for some patients, but cannot be taken consistently because they thicken the urine and strain the kidneys. Some patients find success using these medications (Azo, Pyridium, Uribel) during severe pain flares.

The only FDA-approved oral treatment for interstitial cystitis is Pentosan Polysulfate (PPS, Elmiron®). This is commonly prescribed to patients after an IC diagnosis, but has been shown to be effective in only 28-32% of patients. It also requires a long time (often 6-9 months) to build up in the system and take effect, and many patients stop taking the drug before they could see effect because of side effects (including hair loss) or cost. Unfortunately, many patients lose more than a year after their initial diagnosis waiting to see if Elmiron will work for them, when it is unlikely to provide complete relief.

Antibiotics should never be prescribed for IC in the absence of a confirmed infection.

Bladder and Medical Procedures

Bladder instillations deliver numbing medication directly to the bladder through a catheter and can provide temporary pain relief for some patients. If these are effective, they typically are repeated at least weekly as symptoms return. Some patients don’t tolerate the catheterization well, finding the procedure causes more pain than it prevents. Typical bladder instillations consist of Lidocaine, Heparin, or a combination of the two.

Another route of treatment works by artificially stimulating the nerves the innervate the bladder and pelvic floor.Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) directs electrical impulses from the ankle up through the pelvic floor. This is an outpatient procedure typically performed weekly for a course of 12 weeks. A more permanent option is implanting a device under the skin of the buttock to target the sacral or pudendal nerve root directly.With this procedure, the patient is given a ‘trial run’ with an external device to see how it performs. If significant improvements are noted, the device can be permanently implanted.

Many patients see marked improvement in their symptoms with a home care program. Deep breathing or meditation can calm the nervous system and reduce the amplifying effect of an upregulated nervous system. A stretching regimen targeting the inner thighs, glutes, abdomen, and pelvic floor can relax muscles and reduce nerve irritation in the region. Self-massage can find and eliminate the trigger points that are causing symptoms. Home tools like a foam roller can address external trigger points, while patients can be taught internal self-release with the help of a tool like the PelviWand or another tool.

Elimination Diet

One of the most common misunderstandings about IC centers on the ‘IC Diet.’ In fact, there’s no such thing. While nearly 90% of IC patients report that diet influences their symptoms in some way, the scope and severity of dietary triggers varies greatly between patients. There are a few common culprits - coffee, tea, citrus fruits, artificial sweeteners, tomatoes, cranberry juice - but no guarantee that a patient will be sensitive to all (or any) of these. Many patients read about an ‘IC Diet’ online after receiving their diagnosis, and are convinced that they need to cut out a huge portion of their diet.

Instead, they should be doing an elimination diet focused on identifying their trigger foods.With this approach, they eliminate most of those common culprits and see how it affects their symptoms.If they notice an improvement, they can gradually add foods back into their diet, one at a time, until they see symptoms increase again. This allows patients to identify their specific trigger foods.

Our advice for IC patients is simple - avoid your trigger foods and eat healthy. It doesn’t have to be any more restrictive than that.

There are also several supplements that have shown benefit for patients, either in clinical trials or anecdotally. Prelief (calcium glycerophospate) is an antacid that may reduce the consequences of eating a trigger food. L-Arginine is a semi-essential amino acid that facilitates blood flow and vasodilation; in clinical trials it was shown to be effective for nearly 50% of patients in reducing pain and urinary symptoms. Aloe Vera pills are used by many patients, and thought to help replenish the bladder’s protective layer. Finally, a combination of supplements known as Cystoprotek is also a common supplement taken by IC patients, combining anti-inflammatory flavonoids with molecules that may reinforce the bladder lining.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Acupuncture has been shown to provide relief for pelvic pain patients2, with 73% of men with chronic prostatitis (either identical or closely related to IC) reporting improvement. These men received two treatments weekly for six weeks, focusing around the sacral nerve. Women with pelvic pain and painful intercourse have also reported improvements in pain with 10 sessions of acupuncture3.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce pain in conditions as diverse as cancer, low back pain, and pelvic pain. In pelvic pain, ten one-hour sessions of CBT was shown to provide significant benefit for nearly half of patients4. Supportive psychotherapy was also shown to have benefits for pelvic pain patients.

A multi-disciplinary approach provides the best results for patients. Physical therapists, who see our patients regularly, can be a great resource in suggesting additional treatment options. The American Urological Association IC Guidelines can be an important resource in guiding patients to other options and developing their unique treatment plan.

Information and Resources

For additional patient resources available for download, feel free to visit The IC Solution page.. In our upcoming course for clinicians treating interstitial cystitis (April 28-29, 2018 in San Diego), we’ll focus on the most important physical therapy techniques for IC, home stretching and self-care programs, and information to guide patients in creating a holistic treatment plan.

1. Cozean, N. "Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy in the Treatment of a Patient with Interstitial Cystitis, Dyspareunia, and Low Back Pain: A Case Report". Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 2017

2. Chen R, Nickel JC. "Acupuncture ameliorates symptoms in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome"Urology. 2003 Jun;61(6):1156-9; discussion 1159.

3. Schlaeger, J, et al. "Acupuncture for the Treatment of Vulvodynia: A Randomized Wait‐List Controlled Pilot Study". Journal of Sexual Medicine. 30 January 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12830

4. Masheb, et al. "A randomized clinical trial for women with vulvodynia: Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs. supportive psychotherapy". PAIN® Volume 141, Issues 1–2, January 2009, Pages 31-40

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com/