Pelvic Pain and Enteric Nervous System

This post was written by H&W faculty member Peter Philip, who developed a course on chronic pelvic pain and differential diagnosis for the Institute.

The gut "has a mind of its own." The nervous system within the gut, also called the enteric nervous system (ENS), is located within the sheaths of tissue lining the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and colon. This network consists of neurons, neurotransmitters and proteins that have the distinct capacity to function quite independently. The system can also learn and remember; the joys and sadness that one experiences throughout the day are often reflected within the functional integrity of the enteric nervous system.

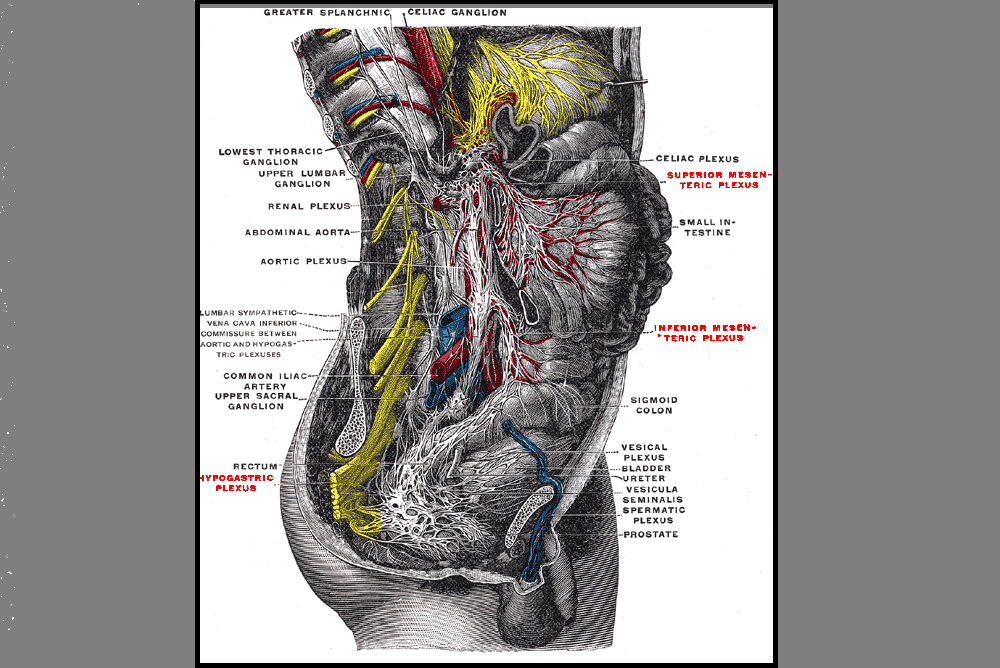

Anatomically, the enteric nervous system is connected to the central nervous system via the vagus nerve. “Command neurons” from the brain communicate with the interneurons of the enteric nervous system via the myenteric and the submucosal plexuses. These command neurons together with the vagus nerve, monitor and control the activity of the gut. The ENS is responsible for motility, for ion transport, gastrointestinal (GI) blood flow, and is associated with secretion and absorption. Sensors for sugar, protein, and acidity are a few of the ways that the contents of the gut are monitored within the system.

The enteric nervous system contains 100 million neurons- more neurons than in the spinal cord! Neuropeptides and other neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, glutamate, norepinephrine and nitric oxide are located within the enteric nervous system. During stressful situations, stress hormones are released in the stereotypical fight-or-flight response, which in turn stimulate the sensory nerves of the ENS, leading to what is experienced as the “butterflies”. Fear also amplifies the release of serotonin leading to a hyperstimulation and resulting in diarrhea. The common experience of “choking under stress” can occur due to stimulation of the esophageal nerves.

Medications and drugs will often have unforeseen consequences on the enteric nervous system, and this is an important fact to consider in patient care. Drugs such as Prozac act by preventing serotonin uptake, which leaves the neurotransmitter at abundant levels in the central nervous system (CNS.) In small concentrations, this effect can cause a hastening of gut motility, and in greater concentrations, motility can be paradoxically retarded. Antibiotics can also impact the receptors of the ENS and produce oscillations, creating symptoms of cramping and nausea. The ENS is responding to stress by increasing secretions of histamines, prostaglandin, and other pro-inflammatory mediators. The purpose is protective in nature, because the brain is preparing the GI for mechanical insult, yet the unfortunate secondary effect is also that of diarrhea and cramping.

Fully understanding the neural integration of the ENS with the CNS, and where along the spinal column afferent information terminates is helpful in understanding our patients who suffer with pelvic and digestive pain. Through the integration and understanding of embryogenesis, the clinician will have a more clear understanding of how and where to apply treatments for optimal pain reduction and restoration of function. During the course, Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Pelvic Pain, the participants will learn about the enteric nervous system's relationship to the central nervous system, and much more!

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com/