Before we talk about yoga, let’s do a quick overview of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome.

In 2022, the American Urological Association updated the clinical guidelines on the treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Prior to this revision, pelvic physical (and occupational) therapy was considered first-line treatment with evidence strength grade A. After this revision, the AUA recommends looking at the phenotype of the patient to determine which treatment categories would best serve the individual patient.

Three phenotypes have been identified: a bladder-centric phenotype, a pelvic floor phenotype, and a phenotype that experiences widespread symptoms with chronic overlapping pain conditions.

As musculoskeletal specialists, we are adept at identifying postural dysfunction. I often explain to patients how their ribcage might shift posteriorly relative to the plumb line and how gravity can amplify forces on specific structures. To help patients understand the difference between their habitual non-optimal posture and a more optimally aligned posture, many occupational and physical therapists use the IPA’s Vertical Compression Test (VCT). This test effectively demonstrates how improved alignment facilitates better weight transfer through the base of support. Sometimes this test reproduces back or pelvic pain which allows the patient to understand how their posture might be a contributing factor to them not feeling their best. In addition to the VCT, I incorporate Mountain Pose as an additional kinesthetic tool for postural retraining.

Many moons ago, I was working with a lovely client on embodied postural awareness using Mountain Pose. I suggested she could close her eyes if she felt comfortable (some people will feel safer lowering their gaze instead of closing their eyes). Working from the ground up, she realized her weight was predominantly in her heels. When I guided her to shift her weight forward by hinging from the talocrural joint, she experienced an “aha moment,” saying, “It feels like my pelvic floor just sighed.” She hadn’t been aware that her habitual posture involved standing with her weight behind the plumb line, which contributed to overactivity of the posterior pelvic floor. Once she adjusted her base of support from the ground up, she felt a significant release in her habitual tension.

At our follow-up visit, the client noted an increase in her postural awareness. She was surprised by how frequently she noticed her pelvic floor gripping in a state of overactivity. She also reported enhanced awareness during her standing yoga postures in class. Grounding down through the feet, cued as imagining the soles of the feet getting magnetically drawn into the floor, can be a useful verbal cue to assist with letting go of unnecessary gripping. The experience of achieving embodied optimal alignment has given her greater self-efficacy, and she’s successfully translated this improved postural awareness into her daily life. Self-awareness and empowerment are central goals in my physical therapy practice, and integrating yoga into this process makes my clinical work even more fulfilling.

B K S Iyengar describes pranayama as an “extension of breath and its control”1. Pranayama, or breathwork, includes inhalation, exhalation, and breath retention. As clinicians treating pelvic health, there are several clinical applications for breathwork.

Mechanical relationship to the pelvic floor

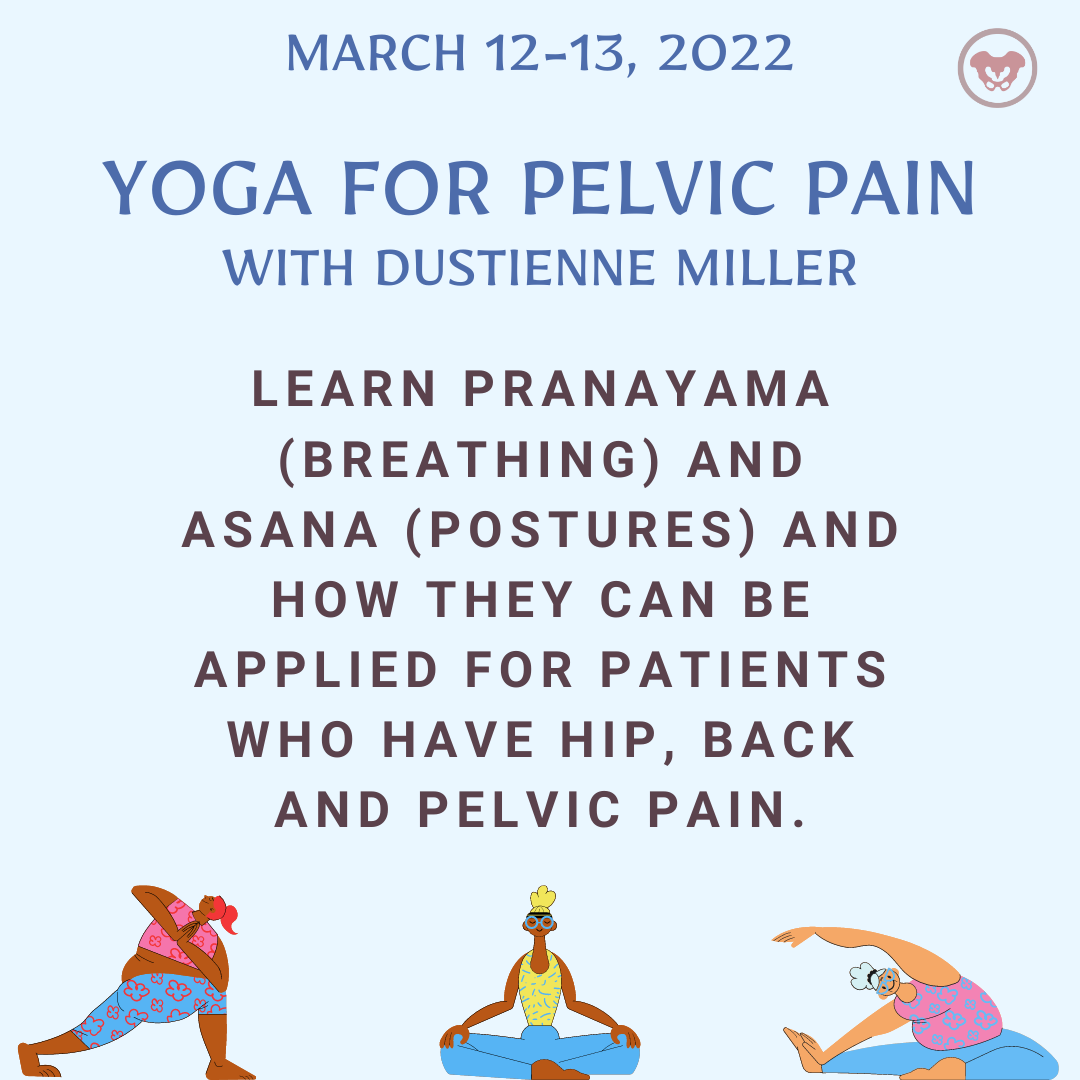

Dustienne Miller, CYT, PT, MS, WCS instructed the H&W remote course Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Dustienne passionately believes in the integration of physical therapy and yoga in a holistic model of care, helping individuals navigate through pelvic pain and incontinence to live a healthy and pain-free life. You can find Dustienne Miller on Instagram at @yourpaceyoga

Research demonstrates multiple benefits of a yoga practice that extend beyond the musculoskeletal system. These benefits include improved mood and depression, changes in pain perception, improved mindfulness and associated improved pain tolerance, and the ability to observe situations with emotional detachment.

Do the brains of yoga practitioners vs non-practitioners look different?

Dustienne Miller is the creator of the two-day course Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Dustienne passionately believes in the integration of physical therapy and yoga in a holistic model of care, helping individuals navigate through pelvic pain and incontinence to live a healthy and pain-free life.

I’m one of the small business owners who has survived this difficult time. Day after day I would mask up, put on the filtration systems, and be filled with gratitude that I could still safely do my work in the world. Despite being vigilant on sleep, eating lots of veggies from the local farm, exercising, and staying well hydrated I still carry a deep covering of stress and tension.

Dustienne Miller MSPT, WCS, CYT is a Herman & Wallace faculty member, owner of Your Pace Yoga, and the author of the course Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Join her in Columbus, OH this April 27-28, to learn how yoga can be used to treat interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, vulvar pain, coccydynia, hip pain, and pudendal neuralgia. The course is also coming to Manchester, NH September 7-8, 2019, and Buffalo, NY on October 5-6, 2019.

How does a yoga program compare to a strength and stretching program for women with urinary incontinence? Dr. Allison Huang1 et al have published another research study, after publishing a pilot study2 on using group-based yoga programs to decrease urinary incontinence. Well-known yoga teachers Judith Hanson Lasater, PhD, and Leslie Howard created the yoga class and home program structure for this research study and the 2014 pilot study. The yoga program was primarily based on Iyengar yoga, which uses props to modify postures, a slower tempo to increase mindfulness, and pays special attention to alignment.

To be chosen for this study, women had to be able to walk more than 2 blocks, transfer from supine to standing independently, be at least 50 years of age, and experience stress, urge, or mixed urinary incontinence at least once daily. Participants had to be new to yoga and holding off on clinical treatment for urinary incontinence, including pelvic health occupational and physical therapy.

As practitioners, we understand the value of a yoga practice for multiple systems. Yoga improves cardiovascular function, pulmonary function, improves flexibility, builds strength, improves balance, and cultivates resiliency. Prenatal yoga is deemed safe and widely practiced. Beyond not laying prone after the first trimester, what are modifications for practicing yoga while pregnant? Is there any evidence to demonstrate if specific yoga postures are safe from both the maternal and fetal perspective?

Polis et al set out to determine the safety of specific yoga postures using vital signs, pulse oximetry, tacometry, and fetal heart rate monitoring. The patients were diverse in age, race, BMI, gestational age, parity, and yoga experience. Exclusionary criteria included preeclampsia, placenta previa, bleeding in the 2nd or 3rd trimester, gestational diabetes, BMI greater than 35 and other medical conditions that presented contraindications.

The maternal and fetal responses were tested in 26 yoga postures. The selected postures, much like most yoga classes, offered a variety of physical positions. The standing, seated, twists and balancing postures chosen were: Easy Pose, Seated Forward Bend, Cat Pose, Cow Pose, Mountain Pose, Warrior 1, Standing Forward Bend, Warrior 2, Chair Pose, Extended Side Angle Pose, Extended Triangle Pose, Warrior 3, Upward Salute, Tree Pose, Garland Pose, Eagle Pose, Downward Facing Dog, Child’s Pose, Half Moon Pose, Bound Angle Pose, Hero Pose, Camel Pose, Legs up the Wall Pose, Happy Baby Pose, Lord of the Fishes Pose and Corpse Pose.

You have been treating a highly motivated 24-year-old woman with a diagnosis of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome (IC/BPS). The plan of care includes all styles of manual therapy, including joint mobilization, soft tissue mobilization, visceral mobilization, and strain counterstrain. You utilize neuromuscular reeducation techniques like postural training, breath work, PNF patterns, and body mechanics. Your therapeutic exercise prescription includes mobilizing what needs to move and strengthening what needs to stabilize. Your patient is feeling somewhat better, but you know she has the ability to feel even more at ease in their day to day. Is there anything else left in the rehab tool box to use?

Kanter et al. set out to discover if mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) was a helpful treatment modality for (IC/BPS). The authors were interested in both the efficacy of a treatment centered on stress reduction and the feasibility of women adopting this holistic option.

The American Urological Association defined first-line treatments for IC/PBS to include relaxation/stress management, pain management and self-care/behavioral modification. Second-line treatment is pelvic health rehab and medications. The recruited patients had to be concurrently receiving first- and second-line treatments, and not further down the treatment cascade like cystoscopies and Botox.

Examples of pranayama

Ujjayi

Letting Go Breath

Today we hear from Herman & Wallace instructor Dustienne Miller CYT, PT, MS, WCS. Dustienne instructs the Yoga for Pelvic Pain course. Join her next month at Yoga for Pelvic Pain, Cleveland, OH on July 18 and 19!

We all know yoga can help chronic headaches, insomnia, anxiety, low back pain, and a myriad of other conditions. How can we apply the principles and benefits of yoga to the treatment of chronic pelvic pain?

Breathing

As rehab professionals who treat chronic pelvic pain, we know how critical it is for our clients to learn how to downtrain the nervous system. Breath awareness and training are a useful tool in reducing sympathetic nervous system override. Some clients may not have the awareness that they are holding their breath because of pain, or even anticipation of pain. Because of the direct mechanical relationship between the diaphragm and the pelvic floor, breath holding can lead to pelvic floor muscle holding. By building awareness, which is a learned skill, the client begins to notice and eventually control non-optimal breathing patterns.