Since I started working with patients with osteoporosis or osteopenia almost 20 years ago, I've noticed an interesting phenomenon. Initially, most patients I saw were in their late 70s and 80s. But within the last 10 to 15 years, the age of my patient population has decreased. I begin receiving referrals for people in their 50s and 60s with osteopenia or osteoporosis after getting their first DEXA scan. Many were traumatized by the diagnosis. They were women who exercised regularly, ate healthily, and took responsibility for a positive lifestyle. It was almost as if they were experiencing PTSD. They were shocked, nervous, and questioning why it happened to them.

One of my first priorities in their care plan was to help calm or down-regulate their sympathetic nervous system. They were in a fight or flight state, and the cortisol running through their bodies was not kind to their bones. I educated them that the DEXA scan only measures bone density and not quality. Quality has come to the forefront as an important component of the lattice-like structures of our bones, yet we still don't have a good way to measure it. I wanted them to understand that the DEXA scan, although it is the gold standard, is only one piece of the puzzle. I used to say, “Let’s pretend your T score is exactly the same as another individual, but that individual is a couch potato who smokes, eats junk food, and basically follows an unhealthy lifestyle. Do you really think your risk of fracture is identical? I wanted them to feel that their actions had had a positive influence on their health, even with the diagnosis. And I truly believe that it does.

Following the evaluation, they started in the Decompression position, also known as hook-lying, and based on the work of Sara Meeks. We explored belly breathing, intercostal breathing, and found the neutral spine position. They were invited to completely relax, allowing the surface of the mat to support them. Not only did this help calm their sympathetic nervous system by activating their “rest and digest” parasympathetic nervous system, but it also placed them in a gravity-eliminated position. Sitting is compressive to the vertebral bodies and discs. Supine positioning allows the anterior aspect of the vertebral bodies (where most spinal compression fractures occur) to decompress. Thus, the name “Decompression position.”

This is the part of physical therapy where it sometimes feels we are doing more mental than physical therapy. But it is an important step. Educating patients is one of the greatest gifts that we can offer in rehabilitation. It not only helps them understand the diagnosis, it also empowers them. Many people with osteoporosis or osteopenia assume their only option is medication. While we certainly do not recommend one option over another, we do educate them that there are multiple ways to manage their disease. A few include site-specific exercises, body mechanics, stress management, and encouraging an educated discussion with their medical provider on the pros and cons of osteoporosis medications. These are steps they can take to feel they have control back in their lives.

From there, we gradually increase their challenges in terms of exercise, balance, and help them return safely to the life they deserve.

Osteoporosis Management: An Introductory Course for Healthcare Professionals provides tools to help your patients move forward with their chronic disease. We hope you'll join us on November 8th for this one-day seminar.

References:

- Jia-Sheng Ng1, Kok-Yong Chin. Potential mechanisms linking psychological stress to bone health. Int J Med Sci. 2021 Jan.

AUTHOR BIO

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT, Balance and Falls Professional (Geriatrics Academy of the APTA)

Dr. Deb Gulbrandson has been a physical therapist for over 48 years, with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to businesses and industries. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area, specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. She and her husband, Gil, a former certified orthotist, “semi-retired” to Evergreen. They teach Osteoporosis management to physical therapists around the country. Deb also works for Mt Evans Homecare and Hospice and sees private patients for physical therapy as well as Pilates clients in her home studio. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country-currently 46 out of 63.

Dr. Deb Gulbrandson has been a physical therapist for over 48 years, with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to businesses and industries. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area, specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. She and her husband, Gil, a former certified orthotist, “semi-retired” to Evergreen. They teach Osteoporosis management to physical therapists around the country. Deb also works for Mt Evans Homecare and Hospice and sees private patients for physical therapy as well as Pilates clients in her home studio. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country-currently 46 out of 63.

Deb is a graduate of Indiana University with a BS in Physical Therapy and a former NCAA athlete, where she competed on the IU Gymnastics team. She has always been interested in movement and function and is grateful to be able to combine her skills as a PT and Pilates instructor. In 2011, she received her Doctorate in Physical Therapy from Evidence in Motion.

Dr. Gulbrandson frequently presents community talks on topics related to Osteoporosis and safe ways to develop Core Strength. She is a certified Pilates Instructor through Polestar Pilates since 2005, a Certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist using the Meeks Method, and has her CEEAA (Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult) through the Geriatric Section of the APTA.

One of the most important concepts in working with people with low bone density (osteopenia or osteoporosis) is reducing the hyper-kyphosis of the spine. Notice I’m saying HYPER-kyphosis, not just kyphosis which should be present in the thoracic spine. Because the anterior portion of the vertebral bodies is where most spinal fractures occur, an increase in the Cobb angle beyond 40-50 degrees places increased pressure on that area. This can result in increased risk of fractures or may be an indication that a fracture has previously occurred.

There are several ways to measure an individual’s thoracic hyper-kyphosis with x-rays being the gold standard. However, we as clinicians can use the Flexicurve, a protocol advanced by physical therapist, Carleen Lindsey. (1)

The Flexicurve ruler is a tool used to measure thoracic kyphosis and can help identify hyper-kyphosis. It is available on Amazon or found in some fabric stores. To use the Flexicurve, the ruler is molded to the patient's thoracic and lumbar curves in standing and then the curves are traced on graph paper. Measurements of the curves are then taken by measuring the width of the T curve, divided by the length of the T curve X 100. A kyphosis index is calculated to quantify the curvature. An index greater than 13 is often considered hyper-kyphotic, according to a study from the NIH. (2)

One of the advantages that I love is that after the measurement is traced on graph paper and dated, the patient has a visual of their spine which helps with exercise compliance. It also helps to explain why we are targeting specific muscles and areas of the spine, not just general strengthening. Following our exercise program, the patient can be re-measured, and the new drawing placed adjacent to the initial one. Patients can see the improvement which further motivates them to keep exercising Typically, with the reduction in thoracic hyper-kyphosis come a subsequent increase in height!

One of the advantages that I love is that after the measurement is traced on graph paper and dated, the patient has a visual of their spine which helps with exercise compliance. It also helps to explain why we are targeting specific muscles and areas of the spine, not just general strengthening. Following our exercise program, the patient can be re-measured, and the new drawing placed adjacent to the initial one. Patients can see the improvement which further motivates them to keep exercising Typically, with the reduction in thoracic hyper-kyphosis come a subsequent increase in height!

So how do we reduce the curve? By strengthening the upper back extensors. First you must make sure the individual is trained in neutral lumbar spine and core control. Many people with hyper-kyphosis compensate by increased lumbar lordosis which often results in lumbar hypermobility and resultant pain. And doesn’t strengthen the upper back.

Once they understand and can maintain neutral lumbar spine, we proceed with the Decompression and Re-alignment Routine developed by Sara Meeks, PT. This is practiced in the supine position and progressed to prone. Using visuals is a great way to “get your ideas of movement” into your patient’s body. I like to use the “person being shot out of a cannon” as my visual. The abdominal stabilization, spinal elongation, and activation of scapulo-thoracic musculature are all embodied in the image.

Educating patients and giving them visuals to see the improvement goes a long way toward helping them remain compliant with their exercise program.

My colleague and partner, Dr. Frank Ciuba and I would welcome you to our upcoming remote course, Osteoporosis Management: An Introductory Course for Healthcare Professionals where you will learn additional assessments and exercises for people with low bone density. Our next courses are scheduled for September 6 or November 8.

References:

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Flexicurve-ruler-measurement-of-kyphosis-A-Mark-the-C7-spinous-process-and-the-L5-S1_fig3_44639136

- J Lam, T Mukhdomi. Kyphosis, Stat Pearls, NIH. (Aug 2023

AUTHOR BIO

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT (she/her) has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT (she/her) has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb is a graduate of Indiana University and a former NCAA athlete, where she competed on the IU Gymnastics team. She has always been interested in movement and function and is grateful to combine her skills as a PT and Pilates instructor. She has been certified through Polestar Pilates since 2005, a Certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist through the Meeks Method since 2008, and a Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult through the Geriatric Section of the APTA.

One of my favorite things as the instructor of the Menopause Transitions course is when participants ask questions. Whether it is something about their own menopause journey or when a patient is struggling with symptoms, it thrills me to provide resources and clarity to help them make informed decisions.

The following are some of the questions that have come up in class or that have been brought to my attention via email after participants are back in the clinic:

Given the many benefits of hormone therapy, should every patient take it during or after perimenopause for the prevention of chronic disease?

This is an excellent question! Based on recommendations from The Menopause Society, hormone therapy is approved for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms, genitourinary symptoms, and the prevention of osteoporosis.

Hormones are often lauded as a benefit for reducing both heart disease and dementia. While it has shown some benefit for heart disease, it is not recommended as a preventative treatment. The same holds true for prevention of neurodegenerative disease. The research on the benefits of hormones in cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease reductions is often looking a different outcomes.

Each study may use a different type of estrogen. An oral estrogen blend (Premarin), an estradiol patch, and an oral estradiol can all have different effects on the body. You simply cannot extrapolate data from one study to the next if the type of estrogen studied was different. In addition, some research shows no benefit. Based on the current data, hormones are not a slam dunk for the prevention of heart disease and dementia. More studies with the types of hormones that are currently being prescribed are needed before recommending them as prevention.

Hormone therapy is very effective for improving bone density. Osteoporosis is a painless process of bone loss. If a person is not experiencing hot flashes and is concerned about their risk for osteoporosis, they could opt for a DEXA scan and then make an informed decision with their provider regarding hormone therapy.

Is there a dose of estrogen that is more beneficial for treating osteoporosis?

In the 2021 position statement for the management of osteoporosis, the Menopause Society cites a study that shows improved bone density with increased dosage. Oral estradiol doses of .02mg, .05mg, and .075mg after 2 years of treatment correlated with an improvement in lumbar spine bone density of .4%, 2.3%, and 2.7% (Greenwald et.al, 2005). While improvement can be gained from a smaller dose, a higher dose does have more benefit. Once again, informed decision-making with a knowledgeable provider is needed.

What are your go-to resources for all things menopause?

Based on the answers to the two previous questions, I think you can see that The Menopause Society is the gold standard when it comes to all things menopause. The position statements are available on their website and can be accessed for free. This includes guidelines on hormones, non-hormonal treatments, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, and osteoporosis. They also have monthly practice pearls, which include many pertinent topics on current treatments and health concerns for the patient in the transition.

Another great resource is Jen Gutner’s The Vagenda. While complete articles require a subscription to her Substack, she does offer a free email version that shares information about many of the topics flying around in the social media sphere. Her opinions are not always popular, but they are always research-based.

A final resource would be Women Living Better. This website was started by women frustrated with their own perimenopause experience and has resources for patients wanting to know more about options for treatment and symptoms experienced during this time. The founders have also been responsible for some interesting research regarding a survey of 3200 women in perimenopause. This is also available on their website.

Keep in mind that there are many social media influencers with millions of followers who also offer information. They have YouTube channels, Instagram, and websites. Menopause seems to be everywhere! While it is extremely valuable to get the message out there, the conclusions offered are often oversimplified in the attempt to push a quick and easy narrative. If I have learned anything in my knowledge journey, it is that there is no one-size-fits-all answer. Treatment is very individualized based on health status, risk factors, and personal preferences. Nuance is the key when it comes to offering the best outcomes.

If you would like to learn more on this topic, then join me on April 26-27, 2025, in Menopause Transitions and Pelvic Rehabilitation to understand more about the physiological consequences to the body as hormones decline and how to assist our patients in lifestyle habits for successful aging.

References:

- The 2020 genitourinary syndrome of menopause position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause, 2020. 27(9): p. 976-992.

- Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: the 2021 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause, 2021. 28(9): p. 973-997.

- The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause, 2022. 29(7): p. 767-794.

- Greenwald, M.W., et al., Oral hormone therapy with 17beta-estradiol and 17beta-estradiol in combination with norethindrone acetate in the prevention of bone loss in early postmenopausal women: dose-dependent effects. Menopause, 2005. 12(6): p. 741-8.

- The Nonhormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society" Advisory, P., The 2023 nonhormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause, 2023. 30(6): p. 573-590.

AUTHOR BIO

Christine Stewart, PT, CMPT

Christine Stewart, PT, CMPT (she/her) graduated from Kansas State University in 1992 and went on to pursue her master’s degree in physical therapy from the University of Kansas Medical Center, graduating in 1994. She began her career specializing in orthopedics and manual therapy, then became interested in women’s health after the birth of her second child.

Christine Stewart, PT, CMPT (she/her) graduated from Kansas State University in 1992 and went on to pursue her master’s degree in physical therapy from the University of Kansas Medical Center, graduating in 1994. She began her career specializing in orthopedics and manual therapy, then became interested in women’s health after the birth of her second child.

Christine developed her pelvic health practice in a local hospital with a focus on urinary incontinence and prolapse. She left the practice in 2010 to work at Olathe Health to further focus on pelvic rehabilitation for all genders and obtain her CMPT from the North American Institute of Manual Therapy. She completed Diane Lee’s Integrated Systems Model education series in 2018. Her passion is empowering patients through education and treatment options for the betterment of their health throughout their lifespan. She enjoys speaking to physicians and to community-based organizations on pelvic health physical therapy.

Hi, I’m Deb Gulbranson, co-creator of the course Osteoporosis Management: An Introductory Course for Healthcare Professionals. Along with my partner, Frank Ciuba, we have created a program based on the works of Sara Meeks, whom we taught with for many years.

We know that posture is important, and we may include it in our evaluations, but how do we objectively measure it? How much time do we spend on education, training, exercises, and return demonstration? Chances are, not as much as we should.

Optimal alignment affects our breathing, balance, efficiency of gait, digestion, AND bone density.

In order to increase bone density, we need to weight bear through the skeleton, not in front of it. Compression fractures occur along the anterior aspect of the vertebral bodies. Strengthening the back extensors has also been shown to increase bone density. Therefore, someone with a hyper-kyphotic posture of the thoracic spine is at risk for fracture due to increased pressure anteriorly and overstretched, weakened musculature posteriorly. Statistics show that 1:2 women and 1:4 men will have a fragility fracture due to low bone mass.

How do we objectively measure and describe a person’s alignment?

A quick and simple way is using a wall and measuring tape. Have your patient stand with their heels, sacrum, and thoracic apex of the spine against the wall. There are two options to measure using the OWD or the TWD. Occiput to Wall Distance or Tragus to Wall Distance. The Tragus is the small bump of cartilage in front of the ear canal. Both OWD and TWD have a positive relationship with the Cobb angle, and although they’re not as specific, they are both equally effective. It’s a matter of preference. Frank prefers the TWD since it’s easier to see and measure. However, the score does not tell you how far away from the wall the head is. There will always be a positive number based on the size and shape of the head.

A quick and simple way is using a wall and measuring tape. Have your patient stand with their heels, sacrum, and thoracic apex of the spine against the wall. There are two options to measure using the OWD or the TWD. Occiput to Wall Distance or Tragus to Wall Distance. The Tragus is the small bump of cartilage in front of the ear canal. Both OWD and TWD have a positive relationship with the Cobb angle, and although they’re not as specific, they are both equally effective. It’s a matter of preference. Frank prefers the TWD since it’s easier to see and measure. However, the score does not tell you how far away from the wall the head is. There will always be a positive number based on the size and shape of the head.

I prefer the OWD because whatever the measurement is, it tells me how far forward the head is. 0 equals optimal alignment. The downside is that it’s a little harder to pinpoint the most prominent point of the occiput.

In both cases, the measurement gives us a baseline to measure against. These can be used as screens in a health fair, during a PT screen for patients without a diagnosis of low bone density, and certainly as part of a full eval for patients with known osteoporosis, a compression fracture, or even osteopenia.

These measures, taken periodically, can be very motivating for patients. Generally, we see not only a decrease in the hyper-kyphosis distance but also an increase in height.

This is only one of several ways to assess and describe posture and alignment. We hope you’ll consider joining us to learn more about the treatment protocols and exercise programs in our upcoming Osteoporosis Management course on April 26th.

AUTHOR BIO

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT (she/her) has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT (she/her) has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb is a graduate of Indiana University and a former NCAA athlete, where she competed on the IU Gymnastics team. She has always been interested in movement and function and is grateful to combine her skills as a PT and Pilates instructor. She has been certified through Polestar Pilates since 2005, a Certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist through the Meeks Method since 2008, and a Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult through the Geriatric Section of the APTA.

Ask anyone on the street what one should do for osteoporosis and the typical answer is weight-bearing exercises - and they would be partially right. Weight-bearing, or loading, activities have been shown to increase bone density.(1) But that’s not the whole story. Different exercises have different strain magnitudes, strain rates, and strain frequencies - all of which impact bone density.

- Strain Magnitude - the force or impact of the exercise. Exercises such as gymnastics and weightlifting have a high strain magnitude.

- Strain Rate - the rate of impact of the exercise. Exercises such as jumping or plyometrics have a high strain rate.

- Strain Frequency - the frequency of impact during the exercise session. Exercises such as running have a high strain frequency.

When considering weight-bearing exercises for a home exercise program, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight-bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth, and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture?” We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

An alternative is to focus on odd impact loading. A study by Nikander et a (2) targeted female athletes in a variety of sports classified by the type of loading they apparently produce at the hip region; that is, high-impact loading (volleyball, hurdling), odd-impact loading (squash-playing, soccer, speed-skating, step aerobics), high magnitude loading (weightlifting), low-impact loading (orienteering, cross-country skiing), and non-impact loading (swimming, cycling). The results showed that high impact and odd impact loading sports were associated with the highest bone mineral density.

Marques et al found that odd impact has the potential for preserving bone mass density as does high impact in older women in their 2011 study (3). Activities such as side stepping, figure eights, backward walking, and walking in square patterns help “surprise the bones” due to the different angles of muscular pull on the hip. The benefit, according to Nikander, is that we can get the same osteogenic benefits with less force, moderate versus high impact. This type of bone training would offer a feasible basis for targeted exercise-based prevention of hip fragility.

I tell my osteoporosis patients that if they walk or run the same route, the same distance, and the same speed that they are not maximizing the osteogenic benefits of weight bearing. Providing variety to the bones creates increased bone mass in the femoral neck and lumbar spine.(4)

Dancing is another great activity that combines forward, side, backward, and diagonal motions to movement. In addition, it adds music to make the “weight-bearing exercises” more fun. Due to balance and fall risk, many senior exercise classes offer Chair exercise to music. Unfortunately sitting is the most compressive position for the spine and is particularly problematic with osteoporosis patients. Also, the hips do not get any weight-bearing benefit. Whenever safely possible, have patients stand; you can position two kitchen chairs on either side, much like parallel bars, to hold on to while they “dance.”

Providing creativity in weight-bearing activities using odd impact allows not only for fun and stimulation and offers more “bang for the buck!”

Build on your knowledge of osteoporosis management by joining Deb Gulbrandson and Frank Ciuba in their upcoming short course Osteoporosis Management scheduled for January 25! Not only will you gain a deeper understanding of the scope of the problems, and specific tests for patients with osteoporosis, but you will also learn skills for evaluating patients as well as appropriate safe exercises for an Osteoporosis program.

Resources:

- Mosekilde L. Age-related changes in bone mass, structure, and strength--effects of loading. Z Rheumatol (2000); 59 Suppl 1:1-9.

- Nikander et al. Targeted exercises against hip fragility. Osteoporosis International (2009)

- Marques et al. Exercise effects on bone mineral density in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Epub 2011 Sep 16

- Weidauer L. et al. Odd-impact loading results in increased cortical area and moments of inertia in collegiate athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol (2014)

- Benedetti MG, Furlini G, Zati A, Letizia Mauro G. The Effectiveness of Physical Exercise on Bone Density in Osteoporotic Patients. Biomed Res Int. 2018 Dec 23;2018:4840531. doi: 10.1155/2018/4840531. PMID: 30671455; PMCID: PMC6323511.

AUTHOR BIO:

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb is a graduate of Indiana University and a former NCAA athlete where she competed on the IU Gymnastics team. She has always been interested in movement and function and is grateful to combine her skills as a PT and Pilates instructor. She has been certified through Polestar Pilates since 2005, a Certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist through the Meeks Method since 2008, and a Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult through the Geriatric Section of the APTA.

When thinking of the Developmental Sequence (Supine, Side-lying, Prone, Quadruped, Tall Kneeling, Half-kneeling, Standing, and Walking), I used to think of either pediatrics or people with strokes. However, the developmental sequence can be very useful from an orthopedic standpoint specifically with osteoporosis patients.

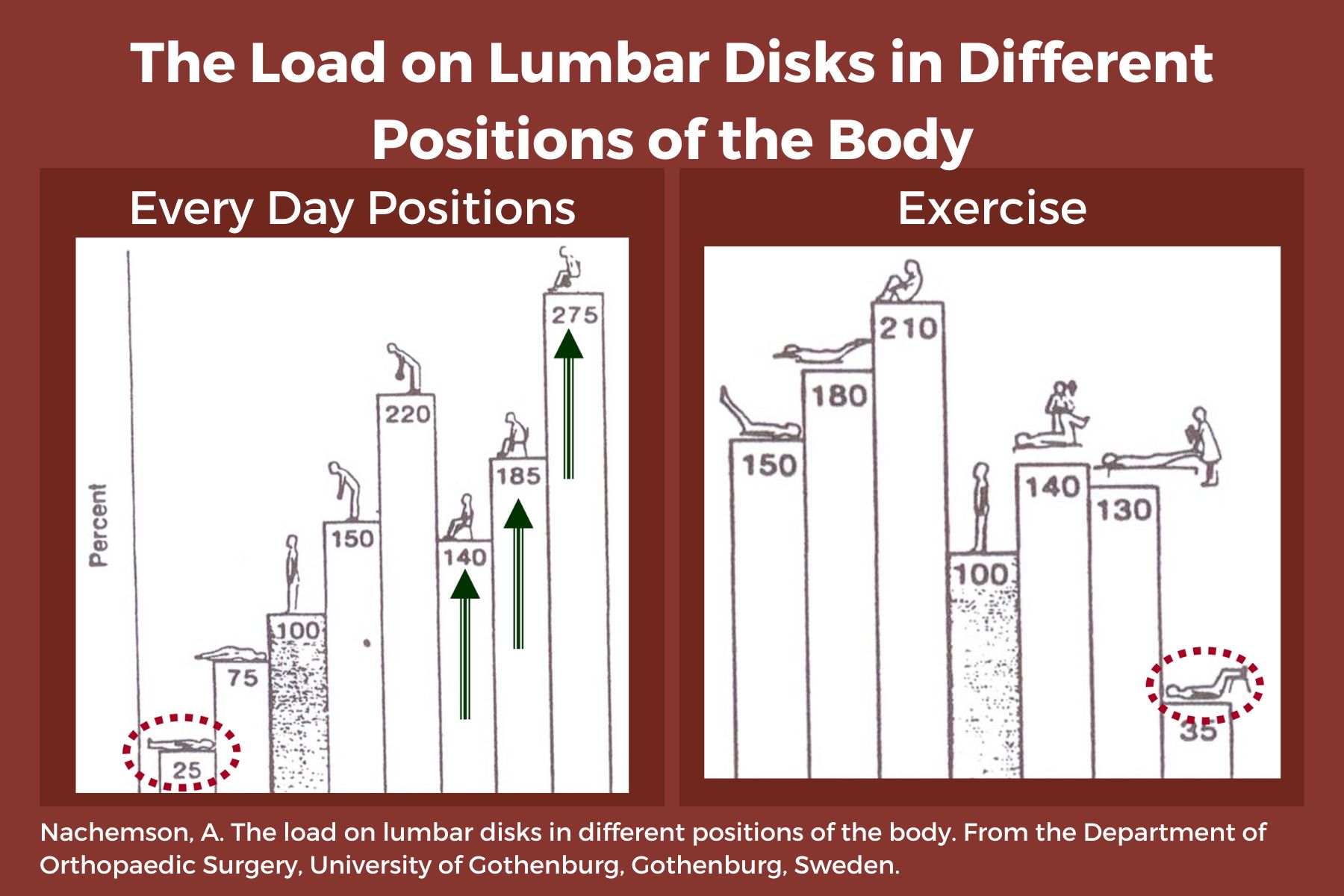

We know that sitting is the most compressive position for our spines, yet repeatedly, I see physical therapists start exercise programs in sitting. There are several reasons I’d like you to consider starting patients in supine.

- Sitting increases intradiscal pressure. (1)

- Supine is a restful position, allowing tense muscles to relax, and can be a great way to reduce anxiety and cortisol running through the body. Ensure that the patient is propped with knees flexed or pillows under the knees, and forearms supported if there is tightness in the biceps.

- Patients can now concentrate on their breath, become aware of any “holding patterns” of tension throughout their body, and free up the mind to focus on learning new skills.

- When we are in higher levels of positioning-sitting, standing, or walking, our brain is focused on survival such as “not falling”. We have many more muscles and joints to control - ankles, knees, hips, etc. This reduces our ability to focus on learning new skills such as engaging the core muscles, relaxing the neck, stop clenching the fingers, etc.

- Preparation is key. We must help our patients gain mastery at one level and then move to the next. Once a patient can understand and find a neutral spine in prone, they are ready to move to side-lying.

- Side-lying can be very beneficial in teaching neutral spine because side-lying is “discombobulating.” We get lost in space and default to the fetal position - a flexed, contra-indicated posture for people with osteoporosis. Use a dowel rod or broom handle to provide feedback from the occiput to the mid-thoracic spine to the sacrum. Have your patient straighten their knees and hips so that, “If you were lying with your back against an imaginary wall, the back of your head, upper back, sacrum, and heels would touch the wall.”

- Prone: Not every osteoporosis patient you see will be able to ultimately transition to prone, but a high majority can and should. Again, propping is critical to allow any anatomical limitations such as shoulder tightness. Use a pillow longitudinally rather than transversely across the abdomen to elevate the shoulders so they can flex to allow the forehead on the hands. If not, keep arms by their side and provide a towel roll under the forehead. This position requires several “stages” of advancement over time and education to engage transversus abdominus, especially for those with spinal stenosis and/or tight hip flexors. The feet should be off the edge of the bed to allow for tightness in plantarflexion.

Working with patients in these three basic positions, while focusing on intercostal breathing, muscle relaxation of the neck, fingers, and other compensatory patterns as we move up the chain, builds a foundation to prepare for functional activities of sit-to-stand, static standing, and movement. These are not stepping stones to be skipped in order to jump into the higher-level functional activities. You would not build a house without a firm foundation. Make sure your patient has the building blocks necessary for the best possible outcomes.

Please join Frank Ciuba and me for our upcoming remote course: Osteoporosis Management: An Introductory Course for Healthcare Professionals on Saturday, Nov 2, 2024. We will discuss osteoporosis-safe exercises, balance and gait activities, and additional ways to help your patients build a strong foundation for movement competence!

Reference:

- Comparison of In Vivo Intradiscal Pressure between Sitting and Standing in Human Lumbar Spine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal ListLife (Basel) PMC8950176 Jia-Qi Li,1 Wai-Hang Kwong,1,* Yuk-Lam Chan,1 and Masato Kawabata2

AUTHOR BIO:

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb is a graduate of Indiana University and a former NCAA athlete where she competed on the IU Gymnastics team. She has always been interested in movement and function and is grateful to combine her skills as a PT and Pilates instructor. She has been certified through Polestar Pilates since 2005, a Certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist through the Meeks Method since 2008, and a Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult through the Geriatric Section of the APTA.

When thinking of the Developmental Sequence (Supine, Side-lying, Prone, Quadruped, Tall Kneeling, Half-kneeling, Standing, and Walking), I used to think of either pediatrics or people with strokes. However, the developmental sequence can be very useful from an orthopedic standpoint specifically with osteoporosis patients.

We know that sitting is the most compressive position for our spines, yet repeatedly, I see physical therapists start exercise programs in sitting. There are several reasons I’d like you to consider starting patients in supine.

- Sitting increases intradiscal pressure. (1)

- It is a restful position, allowing tense muscles to relax, and can be a great way to reduce anxiety and cortisol running through the body. Ensure that the patient is propped with knees flexed or pillows under the knees, and forearms supported if there is tightness in the biceps.

- Patients can now concentrate on their breath, become aware of any “holding patterns” of tension throughout their body, and free up the mind to focus on learning new skills.

- When we are in higher levels of positioning-sitting, standing, or walking, our brain is focused on survival such as “not falling”. We have many more muscles and joints to control - ankles, knees, hips, etc. This reduces our ability to focus on learning new skills such as engaging the core muscles, relaxing the neck, stop clenching the fingers, etc.

- Preparation is key. We must help our patients gain mastery at one level and then move to the next. Once a patient can understand and find a neutral spine in prone, they are ready to move to side-lying.

- Side-lying can be very beneficial in teaching neutral spine because side-lying is “discombobulating.” We get lost in space and default to the fetal position - a flexed, contra-indicated posture for people with osteoporosis. Use a dowel rod or broom handle to provide feedback from the occiput to the mid-thoracic spine to the sacrum. Have your patient straighten their knees and hips so that, “If you were lying with your back against an imaginary wall, the back of your head, upper back, sacrum, and heels would touch the wall.”

- Prone: Not every osteoporosis patient you see will be able to ultimately transition to prone, but a high majority can and should. Again, propping is critical to allow any anatomical limitations such as shoulder tightness. Use a pillow longitudinally rather than transversely across the abdomen to elevate the shoulders so they can flex to allow the forehead on the hands. If not, keep arms by their side and provide a towel roll under the forehead. This position requires several “stages” of advancement over time and education to engage transversus abdominus, especially for those with spinal stenosis and/or tight hip flexors. The feet should be off the edge of the bed to allow for tightness in plantarflexion.

Working with patients in these three basic positions, while focusing on intercostal breathing, muscle relaxation of the neck, fingers, and other compensatory patterns as we move up the chain, builds a foundation to prepare for functional activities of sit-to-stand, static standing, and movement. These are not stepping stones to be skipped in order to jump into the higher-level functional activities. You would not build a house without a firm foundation. Make sure your patient has the building blocks necessary for the best possible outcomes.

Please join Frank Ciuba and me for our upcoming remote course: Osteoporosis Management: An Introductory Course for Healthcare Professionals on Saturday, Nov 2, 2024. We will discuss osteoporosis-safe exercises, balance and gait activities, and additional ways to help your patients build a strong foundation for movement competence!

Reference:

- Comparison of In Vivo Intradiscal Pressure between Sitting and Standing in Human Lumbar Spine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal ListLife (Basel) PMC8950176 Jia-Qi Li,1 Wai-Hang Kwong,1,* Yuk-Lam Chan,1 and Masato Kawabata2

AUTHOR BIO:

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb is a graduate of Indiana University and a former NCAA athlete where she competed on the IU Gymnastics team. She has always been interested in movement and function and is grateful to combine her skills as a PT and Pilates instructor. She has been certified through Polestar Pilates since 2005, a Certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist through the Meeks Method since 2008, and a Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult through the Geriatric Section of the APTA.

Movement competence (or Movement Literacy) is defined as the development of sufficient skills to ensure successful performance in different physical activities. Often used in the world of sports and youth, it also applies to our everyday activities. For example, standing up from a chair or toilet, getting in/out of a car, moving our body from Point A to Point B (and the difference between the ground being even and dry vs uneven and icy).

In our course, Osteoporosis Management: An Introductory Course for Healthcare Professionals, Dr Frank Ciuba and I approach the starting point for individuals with low bone mass (osteopenia or osteoporosis), from an “optimal alignment position.” Patients start supine with hips and knees flexed and are educated on what optimal alignment feels like. Many need to be propped using pillows, towels, or blocks behind their heads, forearms, or between their knees to achieve “their optimal alignment.” Breathing and awareness play a huge role in activating core musculature to sustain this alignment when moving to a vertical position such as sitting or standing. In vertical, our weight-bearing forces and gravity should pass down through the skeleton to take advantage of bone-building benefits. We use dowel rods, broom handles, and walls to give feedback. Optimal alignment can and should be taught in a variety of positions: side-lying, prone, hands and knees, ½ kneeling as we move up the developmental chain.

Hip Hinging, a well-known concept by therapists, must be practiced and mastered for patients with low bone mass to reduce the risk of vertebral fractures. Activities that involve bending at the waist such as brushing teeth, making a bed, and putting dishes in the dishwasher all place the anterior portion of the vertebral bodies under pressure and increase fracture risk.

Advancing from static optimal alignment postures to dynamic optimal alignment is a whole different ballgame; akin to advancing from sitting in a car to driving a car. There are many moving parts - pun intended.

Just as in athletics, mastery comes from repetition. It is not enough to teach patients a safe movement pattern one time, hand them a sheet of paper with pictures, and expect them to be able to comply and gain competence. Reinforcing proper technique and helping them become aware of compensation strategies (hunching shoulders when lifting objects, overarching the back when reaching overhead, etc.) are critical if Movement Competency is to “stick.”

I like to think of movement competency as building a house. First, you need a firm foundation before putting up the walls and roof. Our patients require that foundation to be able to layer on more complicated patterns of movement.

Please join us for this one-day course on September 14th or November 2nd to learn more Osteoporosis-safe exercises, balance and gait activities, and additional ways to help your patients build a strong foundation for movement competence!

AUTHOR BIO:

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb is a graduate of Indiana University and a former NCAA athlete where she competed on the IU Gymnastics team. She has always been interested in movement and function and is grateful to combine her skills as a PT and Pilates instructor. She has been certified through Polestar Pilates since 2005, a Certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist through the Meeks Method since 2008, and a Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult through the Geriatric Section of the APTA.

An interview with Frank Ciuba.

Frank Ciuba, co-instructor of Osteoporosis Management< alongside Deb Gulbrandson, explains that practitioners need the information provided in their course. "This course is the latest up-to-date research compiled by my partner Deb Gulbrandson and myself in the management of osteoporosis for clinicians." He shares that similar to learning about the pelvic floor, "when physical therapists go to school they get only a small amount of what osteoporosis is and very little on how to treat a patient."

Frank explains that he became interested in teaching osteoporosis management when he learned "that one in four men statistically will get osteoporosis or an osteoporosis-related fracture in their lifetime and they're really not being identified." Osteoporosis Management provides an exercise-oriented approach to treating these patients and it covers specific tests for evaluation, appropriate safe exercises and dosing, basic nutrition, and ideas for marketing your osteoporosis program.

In pelvic health rehabilitation, it's seen that osteoporosis-related kyphosis (curvature of the spine) can affect pelvic organ prolapse, breathing, and digestion. Patients who go through the osteoporosis management program with Frank and Deb, are shown that they reduce the likelihood of compression fracture by 80%.

This course, Osteoporosis Management, is not just for practitioners working with osteoporosis or osteopenia patients. Frank lists the types of patients he's been able to help. "I've used this on high school backpack syndrome, whiplash injuries, adhesive capsulitis, spinal stenosis, low back pain, lumbar strain, even some hip pathologies." He concludes with "We just need to get the word out to more individuals that this a program that can help them. Not only in the short term, but in the long term. This is a program for life."

Holly Tanner Short Interview Series - Episode 2 featuring Deb Gulbrandson

Holly Tanner and Deb Gulbrandson sat down to discuss the Osteoporosis Management Remote Course and why it is important for practitioners to recognize and know how to safely treat and manage osteoporosis patients in their practices.

Deb Gulbrandson shares the goal of the Osteoporosis Management remote course: "This course is based on the Meeks Method created by Sara Meeks, PT, MS, GCS...we have branched out to add information on sleep hygiene, exercise dosing, and basic nutrition for a person with low bone mass. Knowing how to recognize signs, screen for osteoporosis, and design an effective and safe program can be life-changing for these patients."

Join H&W at the Osteoporosis Management remote course, scheduled for September 18-19, 2021, to learn more about treating patients with osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis is known to be a painless, progressive condition that leads to a weakening of the bones and can lead to a higher risk for broken bones. The upcoming remote course, Osteoporosis Management, scheduled for September 18-19, 2021, will discuss the scope of problems, specific tests for evaluating patients, appropriate safe exercises and dosing, and basic nutrition.

H&W faculty member Deb Gulbrandson recommends using the National Osteoporosis Foundation database for a resource and emphasizes the prevalence of osteoporosis is in a past interview for the Pelvic Rehab Report. "Approximately 1 in 2 women over the age of 50 will suffer a fragility fracture in their lifetime...According to the US Census Bureau, there are 72 million baby boomers (age 51-72) in 2019. Currently, over 10 million Americans have osteoporosis and 44 million have low bone mass."

A well-known consequence of osteoporosis is the increased risk of fragility fractures. A fragility fracture is often the first sign of osteoporosis and can be the cause of pain, disability, and quality of life for the patient. Research by Marsha van Oostwaard provided data that suggests about 13 percent of men and 40 percent of women with osteoporosis will experience a fragility fracture in their lifetime. Men also have a higher rate of mortality from fragility fractures relative to women (1).

The International Osteoporosis Foundation reports that patients who have suffered from a fragility fracture are at a high risk of experiencing secondary fractures, especially within two years of the initial fracture. Fragility fractures can result in osteoporotic patients from events that would not elicit an injury in a healthy adult. These events can include falling from a standing position and other low-energy traumas.

Fragility fractures are characterized by low bone mineral density and have an increased incidence with age (2). The risk of a fragility fracture is also influenced by bone geometry and microstructure. The most serious fracture sites are at the hip and vertebrae, but fractures can occur also on the ribs and other locations. Healthcare practitioners can assist patients in adapting lifestyle factors including exercise, sleep positions, and nutrition with the aim of helping prevent falls from occurring.

Deb Gulbrandson shares the goal of the Osteoporosis Management remote course: "This course is based on the Meeks Method created by Sara Meeks, PT, MS, GCS...we have branched out to add information on sleep hygiene, exercise dosing, and basic nutrition for a person with low bone mass. Knowing how to recognize signs, screen for osteoporosis, and design an effective and safe program can be life-changing for these patients."

Join H&W at the Osteoporosis Management remote course, scheduled for September 18-19, 2021, to learn more about treating patients with osteoporosis.

- Fragility Fracture Nursing: Holistic Care and Management of the Orthogeriatric Patient [Internet]. Marsha van Oostwaard. Hertz K, Santy-Tomlinson J. Springer; 2018.

- The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Kanis, J.A., et al. Osteoporos Int, 2001. 12(5): p. 417-27.