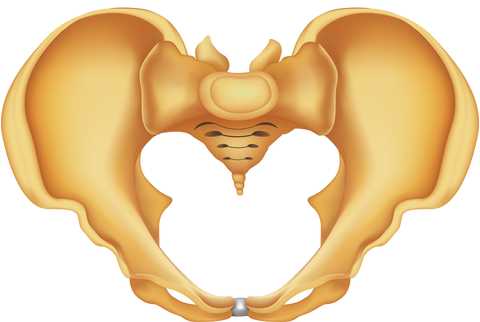

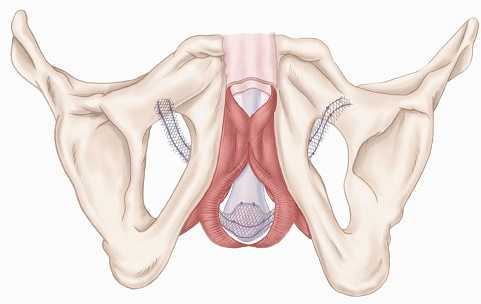

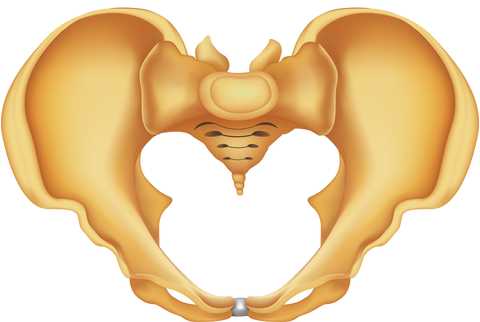

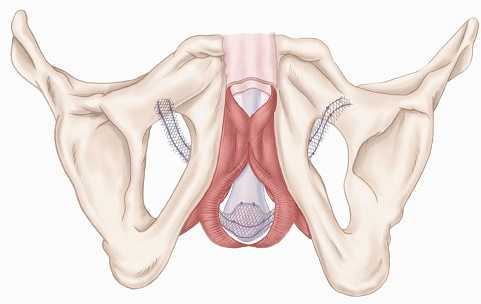

Dyssynergic defecation occurs when the pelvic floor muscles (PFM) are not coordinating in a manner that supports healthy bowel movements. Ideally, emptying of the bowels is accompanied by a lengthening, or bearing down of the PFM, and with dyssynergia, the muscles instead shorten. Because a portion of the levator ani muscles slings directly around the anorectal junction (where the rectum meets the anal canal when the muscles are tight, the "tube" where the fecal material has to pass through narrows, making it difficult to pass stool. If emptying the bowels is difficult, patients will often strain for prolonged periods of time, an unhealthy pattern for the abdominopelvic area, and constipation may occur due to the stool remaining in the colon for prolonged periods of time, where the water is reabsorbed from the stool, becoming harder and more difficult to pass.

Can patients with this condition be helped by pelvic rehabilitation providers? Absolutely, with correction of muscle use patterns, bowel re-training education, food and fluid recommendations, and pelvic muscle rehabilitation addressed at optimizing the muscle health. Much of the time, patients with this dysfunctional muscle use pattern present with tension and shortening in the pelvic floor muscles, although they may also present with muscle lengthening and weakness. Surface electromyography (sEMG a form of biofeedback, has also been utilized and the literature supports sEMG for bowel dysfunctions including dyssnergia.

Another technique used by pelvic rehabilitation providers for re-training dyssynergia (also known as non-relaxing puborectalis, or paroxysmal puborectalis, naming the muscle fibers that sling around the rectum) is the use of balloon-assisted training. In this technique, a small, soft balloon is inserted into the rectum and is attached to a large syringe that will inject either water or air into the balloon, causing the balloon to enlarge within the rectum. This training technique allows the patient to provide feedback about sensation of rectal filling including when the patient perceives urges to defecate. The patient can practice expelling the balloon, and in the event of a dyssynergic pattern of pelvic floor muscles, the balloon would not be expelled due to increased muscle tension and shortening of the anorectal area. In this manner, the patient is trained to bring awareness to the anorectal area, and to respond with healthy patterns of defecation.

One study that compared biofeedback training to balloon-assisted training found that biofeedback was more effective in training patients for reduction of constipation. 65 patients, 49 women and 16 men, were included and were diagnosed with constipation and dyssynergia. In the balloon training (n = 31 patients were trained to expel the balloon with increased abdominal pressure and relaxed PFM, whereas in the biofeedback group (n = 34 the patients were trained to relax the pelvic floor muscles while increasing abdominal pressure. The good news is that while the biofeedback group reported higher levels of success in emptying, both groups reported positive effects of their training, with improved amount of stool passed, decreased maneuvers required to empty the bowels, and decreased time needed to defecate.

If you would like to learnabout sEMG for bowel dysfunction, sign up for the Pelvic Floor series 2A continuing education course. We are sold out for the rest of the year for PF2A, and the next opportunity to take the course will be next March in Madison, Wisconsin, or May of 2015 in Seattle. If you want to learn how to use balloon-assisted re-training techniques, you still have an opportunity this year to get into a course. Faculty member Lila Abatte has developed the Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction, the Pelvic Floor course that still has seats left for the November, Torrance, California course.

Pelvic rehabilitation providers typically evaluate basic nutritional influences on a patient's bowel and bladder function. Instructing in dietary irritants, adequate and appropriate fluid intake (more water, less soda, for example and in the importance of whole foods and fiber's effects on the bowels is commonly included in a rehabilitation program. Although most therapists are not nutritionists, this level of patient education frequently improves a patient's function significantly, and has little potential for harm in the absence of medical conditions that may require fluid restriction, or avoidance of particular foods.

What is known about the impact of diet on commonly treated conditions? Consider interstitial cystitis, also known as painful bladder syndrome, and the varied experiences our patients report: for some, diet limitations dramatically control a patient's flare-ups, for others, there appears to be no rhyme or reason to diet and dysfunction. For patients who have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS research has suggested that a diet low in FODMAPS (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) may reduce the pain, bloating, and gastrointestinal symptoms in general. Other research describes the positive effect of the oligo-antigenic, sometimes described as a "severe" elimination diet, on the healing of chronic anal fissures.

The impact of nutrition on health and healing extends far beyond bowel and bladder dysfunctions as described above, but what is fact and what is fiction? Does the basic sciences research support the claims about nutrition's affects on pain and pelvic health? When is a pelvic rehabilitation provider obligated to refer a patient to a nutritionist or other provider? What resources are available to the clinician and to the patient when additional supportive services are not available? The Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute is thrilled to offer answers to all of the above questions through a new continuing education course on Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist that was written by Megan Pribyl, a physical therapist who also holds a dual-degree in nutrition and exercise sciences. From basic sciences, gastrointestinal anatomy, high-level functional nutritional concepts, to practical applications for the pelvic rehabilitation therapist, this course can provide the clinician with updated knowledge about the relationships and influences of nutrition on healing.

This course will be offered in Seattle, WA at the end of August- the perfect time to plan one last trip before back-to-school!

According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 233,000 new cases of prostate cancer will be diagnosed this year, and nearly 30,000 men will die from the disease. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer in the United States has experienced significant shifts in the past few years, making management of cancer survivors challenging. One of the big changes in prostate cancer screening took place in 2011; the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended against routine prostate specific antigen, or PSA testing due to the level of potential harm such as psychological distress and complications from the biopsy. You can read a prior post about that here. New guidelines for providing care to prostate cancer survivors have been published by the American Cancer Society so that providers can better identify and manage the side effects and complications of the disease and recognize appropriate monitoring and screening of survivors.

In patients younger than 65 years of age, radical prostatectomy surgery is the most common intervention for prostate cancer. Long-term side effects of radical prostatectomy commonly include, according to the guidelines, urinary and sexual dysfunction. Urinary incontinence or retention can occur following prostatectomy, and sexual issues can range from erectile dysfunction to changes in orgasm and even penile length. Other common treatments, such as radiation and androgen deprivation therapy, are also related to urinary, sexual, and bowel dysfunction, as well as a long list of "other" effects.

These guidelines were developed using evidence as well as expert recommendations. Topics covered include obesity, physical activity, nutrition, smoking cessation, and surveillance. BMI as a baseline measure is recommended as a screening tool because elevated BMI is associated with poorer health outcomes. Increased physical activity can be related to higher quality of life and general benefits in cardiorespiratory health and physical function. Exercise recommendations are for 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity exercise or 75 minutes/week of vigorous intensity physical exercise. Nutrition suggestions include eating a diet that is rich in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains. Because smoking after prostate cancer increases the risk of recurrence, therapists should discuss the benefits of smoking cessation.

All of the above issues concern pelvic rehabilitation providers; patient concerns about sexual heath, urinary and bowel health, and subsequent pain in the abdomen or pelvis following treatment for prostate cancer are all conditions that can be positively influenced in the clinic. All of the lifestyle and wellness recommendations are ones that can be reinforced in pelvic rehabilitation, and patients can be referred for more specialized education when needed. To learn more about the care of men following prostate cancer, come to Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction, & Treatmentcontinuing education course in October in Tampa. Also, stay tuned for an announcement about our new Rehabilitation of the Post-Prostatectomy Course coming in 2015! (Send us an email if you are interested in hosting the new continuing education course that will focus on post-prostatectomy (and related issues) recovery!)

In pelvic rehab, if you ask therapists from around the country, you will most often hear that patients with pelvic dysfunction are seen once per week. This is in contrast to many other physical therapy plans of care, so what gives? Perhaps one of the things to consider is that most patients of pelvic rehab are not seen in the acute stages of their condition, whether the condition is perineal pain, constipation, tailbone pain, or incontinence, for example.

The literature is rich with evidence supporting the facts that physicians are unaware of, unprepared for, or uncomfortable with conversations about treatment planning for patients who have continence issues or pelvic pain. The research also tells us that patients don't bring up pelvic dysfunctions, due to lack of awareness for available treatment, or due to embarrassment, or due to being told that their dysfunction is "normal" after having a baby or as a result of aging. So between the providers not talking about, and patients not bringing up pelvic dysfunctions, we have a huge population of patients who are not accessing timely care.

What else is it about pelvic rehab that therapists are scheduling patients once a week? Is it that the patient is driving a great distance for care because there are not enough of us to go around? Do the pelvic floor muscles have differing principles for recovery in relation to basic strengthening concepts? Or is the reduced frequency per week influenced by the fact that many patients are instructed in behavioral strategies that may take a bit of time to re-train?

Pelvic rehabilitation providers are oftentimes concerned about the plans of care (POC) being once per week not because patients always need more visits, but because insurance providers are accustomed to seeing a POC with ranges of 2-3 visits per week, and in some cases, even 4-7 visits per week, based upon diagnosis, facility, and patient needs. To justify and support our once per week POC, we need only look to research protocols, to clinical care guidelines, and to clinical recommendations and practice patterns of our peers. For the following conditions, most of the cited research uses a once per week (or less) protocol or guideline:

Braekken et al., 2010: randomized, controlled trial with once per week visits for first 3 months, then every other week for last 3 months.

Croffie et al., 2005: 5 visits total, scheduled every 2 weeks.

Fantl & Newman, 1996: Meta-analysis of treatment for urinary incontinence, recommends weekly visits.

Fitzgerald et al., 2009: Up to 10 weekly treatments (1 hour in duration) was used in the largest randomized, controlled trial of chronic pelvic pain.

Hagen et al., 2009: Randomized, controlled trial using an initial training class, followed by 5 visits over a 12 week period.

Terra et al., 2006: Protocol used 1x/week for 9 weeks.

Weiss, 2001: 1-2 visits per week for 8-12 weeks.

Vesna et al., 2011: Children were randomized into 2 treatment groups with 1 session per month for the 12 month treatment period.

While not every patient is seen once per week in pelvic rehabilitation, Herman & Wallace faculty can tell you that once a week is the most common practice pattern observed for urinary dysfunction, prolapse, and pelvic pain. Certainly, a patient with an acute injury, a need for expedited care (limited insurance benefits, goals related to upcoming return to work or travel plans, or insurance expectations that dictate plan of care) may lead to frequency of visits that are more than once per week.

If you are interested in learning more about treatment care plans for a variety of pelvic dysfunctions, sign up for one of the pelvic series courses, and for special populations such as pediatrics, check out the Pediatric Incontinence continuing education course taking place in South Carolina at the end of this month!

References

Braekken, I. H., Majida, M., Engh, M. E., & Bo, K. (2010). Can pelvic floor muscle training reverse pelvic organ prolapse and reduce prolapse symptoms? An assessor-blinded, randominzed, controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 203(2), 170.e171-170.e177. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.037

Croffie, J. M., Ammar, M. S., Pfefferkorn, M. D., Horn, D., Klipsch, A., Fitzgerald, J. F., . . . Corkins, M. R. (2005). Assessment of the effectiveness of biofeedback in children with dyssynergic defecation and recalcitrant constipation/encopresis: does home biofeedback improve long-term outcomes. Clinical pediatrics, 44(1), 63-71.

Fantl, J., & Newman, D. (1996). Urinary incontinence in adults: Acute and chronic management. Rockville, MD: AHCPR Publications.

FitzGerald, M. P., Anderson, R. U., Potts, J., Payne, C. K., Peters, K. M., Clemens, J. Q., . . . Nyberg, L. M. (2009). Adult Urology: Randomized Multicenter Feasibility Trial of Myofascial Physical Therapy for the Treatment of Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes. [Article]. The Journal of Urology, 182, 570-580. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.022

Hagen, S., Stark, D., Glazener, C., Sinclair, L., & Ramsay, I. (2009). A randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training for stages I and II pelvic organ prolapse. International Urogynecology Journal, 20(1), 45-51. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0726-4

Terra, M. P., Dobben, A. C., Berghmans, B., Deutekom, M., Baeten, C. G. M. I., Janssen, L. W. M., ... & Stoker, J. (2006). Electrical stimulation and pelvic floor muscle training with biofeedback in patients with fecal incontinence: a cohort study of 281 patients. Diseases of the colon & rectum, 49(8), 1149-1159.

Weiss, J. M. (2001). Clinical urology: Original Articles: Pelvic floor myofascial trigger points: manual therapy for interstitial cystitis and the urgency-frequency syndrome. . [Article]. The Journal of Urology, 166, 2226-2231. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)65539-5

Vesna, Z. D., Milica, L., Stankovi?, I., Marina, V., & Andjelka, S. (2011). The evaluation of combined standard urotherapy, abdominal and pelvic floor retraining in children with dysfunctional voiding. Journal of pediatric urology, 7(3), 336-341.

Research completed by medical faculty of Heidelberg University in Germany aimed to better understand the characteristics of pain that can be caused by different structures or tissues within the low back. Is the information gained applicable to all layers of tissues in the body? If so, how does that assist with our structural evaluation and interventions? If not, how do various body regions reflect the findings of this study?

Researchers injected saline into tissues of the back of 12 healthy subjects at differing layers of depth and tissue; the injections were guided by ultrasound. (This method of inducing muscle pain has been utilized and refined since the 1930's.) The authors describe prior studies indicating that thoracolumbar fascia is innervated by free nerve endings, and that lumbar dorsal horn neurons receive nociceptive input from fascia; these connections are theorized to relate to fascia as a potential cause of low back pain.

The volunteer subjects were both male (6) and female (6) and none had a history of back pain. 3 sessions were scheduled with at least 5 days between study sessions. Following saline injection, the subjects rated pain at 10 second intervals for two minutes, then at 30 second intervals for the next 23 minutes. Subjects also recorded on a body chart where the symptoms occurred. Pressure pain threshold was recorded using a pressure algometer at baseline and at 25 minutes post-injection. Pain quality was assessed with an outcomes tool that listed both affective and sensory items.

The authors conclude that, in response to saline injection, the thoracolumbar fascia is more sensitive to the chemical irritation than the erector spine muscles or the overlying cutis (the dermis and epidermis, or combined layers of the skin.) Areas of recorded pain were larger for fascial injection than for skin or muscle. However, hyperalgesia to blunt pressure as measured by the pressure pain threshold device could only be created by injections into the muscle. In summary, the article states that injection to the thoracolumbar fascia "…induces intense tonic pain with a strong affective component and a pain radiation similar to acute LBP," whereas hyperalgesia to pressure "…seems to require peripheral sensitization of muscle nociceptors."

Does this research offer a window into the symptomatology and etiology of varying pain complaints? Can we direct our treatment to the tissues that appear to be at fault? The more we know about the tissues of the body, how to differentiate structurally the ways in which pathologies present, perhaps we will continue to build our clinical reasoning upon the anatomy and pathological findings. For more research and clinical applications surrounding fascia, you still have time to sign up for faculty member Ramona Horton's courses on myofascial evaluation and interventions for pelvic dsyfunction.

For patients who are diagnosed with constipation, functional anorectal testing is often completed prior to referral for physical therapy. A recent study concluded that clinical examination of pelvic floor muscle function is critical for identifying a rectocele or pelvic muscle overactivity, and that anorectal function tests should be reserved for selected cases. Pelvic rehabilitation therapists are able to perform tests of the pelvic muscles and function during a patient's attempts to contract, relax, and bear down through the pelvic floor. These tests are easy to repeat and a patient can be instructed in corrective muscle techniques to improve the ability to empty the bowels.

Consider the patient who presents to the clinic after experiencing a defecography. In this test, a patient undergoes an imaging study while sitting on an elevated toilet seat. The patient is asked to bear down to evacuate a bolus of material that is placed inside the rectum. It is easy to understand why a patient finds this test to be "embarrassing." Following this test, when a patient is diagnosed with dyssynergia (when the puborectalis muscle contracts rather than lengthening and relaxing during attempt to defecate) he or she is frequently referred to pelvic rehabilitation. A pelvic rehab therapist can observe and palpate the same phenomena in the clinic: when asked to bear down or drop the pelvic floor muscles, if a patient instead contracts or is unable to lengthen the muscles, re-training can be implemented.

I have often wondered why a patient would need to complete this type of testing for constipation-related pelvic muscle dysfunction if the same patient could reverse a dysfunctional muscle pattern with a brief bout of pelvic rehabilitation. The research by Lam and Felt-Bersma (full-free text article linked above) appears to confirm this thought, concluding that anorectal functional testing contributes little to information that can be gained in clinical examination in women who have idiopathic constipation.

The authors studied 100 women who were diagnosed with idiopathic constipation and who fit the Rome III criteria. A prospective evaluation included an extensive questionnaire regarding complaints, abdominal, rectal, and vaginal examination, and anorectal function tests such as anorectal manometry (ARM)and anal endosonograpy (AUS). Exclusion criteria included inflammatory bowel disease, fissures, or fistula, and endocrine disorders orcolonic obstruction were ruled out. Of these 100 women, 25% were found to have hypertonia and dyssynergia of the pelvic floor, and 15% presented with a rectocele. During anorectal manometry, the authors also noted that women had difficulty relaxing during straining. In the group studied, 37 women complained of impaired evacuation, and interestingly, 40% of these women had a rectocele, yet no rectoceles were identified in the women who did not complain of impaired evacuation.

While medical screening for patients who complain of constipation is important, this research identifies a group of patients (those diagnosed with idiopathic constipation) for whom ARM or AUS testing does not contribute significantly to the evaluative process. The study is very valuable reading for pelvic rehabilitation providers as the authors clearly understand the role of rehabilitation and articulate the value ofpelvic floor muscle function in meaningful ways throughout the report. If you are interested in learning how to evaluate and treat patients who have constipation, there are 3 seats remaining in the PF2A continuing education course at the end of this month in Fairfield, California (right next to Napa, in case that interests you!) The PF2A course covers bowel dysfunction such as constipation, fecal incontinence, and other colorectal conditions, and also offers on Day 3 an Introduction to Male Pelvic Floor function and dysfunction related to pelvic pain and urinary dysfunction. Following the West coast PF2A, there are East coast and Midwest dates, click here to find the course information. Sign up early as this course always sells out!

While the literature is clear that childbirth is a risk factor for pelvic floor dysfunction, how does a first childbirth affect the pelvic floor muscles? Does a vaginal delivery, instrumented delivery, or cesarean delivery affect the muscles differently? These questions were addressed in a prospective, repeated measures study involving 36 women. Outcomes included pelvic muscle function via vaginal squeeze pressure and questionnaires, prior to and following childbirth. The women were first evaluated between 20-26 weeks gestation and again between 6-12 weeks postpartum. All participants were primiparas, meaning that they had not given birth previously, and were found to have a significant decrease in strength and endurance after their first childbirth.

Pelvic floor muscle strength and endurance testing included maximum voluntary contraction (3 repetitions for up to 5 seconds) , sustained contraction, and repeated contractions at least 15 times. Ability to correctly contract the pelvic muscles was assessed via vaginal digital testing (with one examining finger) and perineal observation. A Myomed device was utilized with a vaginal sensor to more accurately measure strength. At the time of postpartum measurement, 33 of the 36 women were breastfeeding, the instrumented deliveries were completed with vacuum extraction, and all episiotomies were performed as right mediolateral procedures. Although the women in the study were asked if they completed pelvic muscle exercises- they were not instructed in any specific exercises.

Prior to childbirth, there were no significant differences in pelvic muscle strength and endurance between the three delivery groups. Following vaginal delivery (assisted or unassisted) pelvic muscle strength was significantly reduced, but endurance was not significantly influenced by delivery mode. While in this study, patients who had a cesarean procedure had decreased pelvic muscle dysfunction, the authors also point out that cesarean "…performed for obstructed labor or after the onset of labor has been reported to be ineffective in protecting the pelvic floor."

This study aimed to document the effect of a first childbirth on pelvic muscle strength. The authors acknowledge that controlled studies with larger sample sizes are needed to make further claims about pelvic muscle health postpartum. Ideally, even though pelvic muscle strength is reduced, we can utilize this information to establish connections about labor and delivery, and more importantly, how to minimize the impact or maximize the healing of pelvic muscles following childbirth. To further discuss postpartum issues, join us for Care of the Postpartum Patient in Houston (June) or Chicago (September)!

When assessing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) stability and function, pelvic rehabilitation providers often use the single leg stand test. During transition from double-leg stance to single-leg stance, dynamic stability is required and there are several ways to describe the observed behaviors in patients. If a patient, for example, loses her balance when transitioning to a single leg stand, what is contributing to her loss of stability? Could it be the SIJ, abdominal and trunk strength, ankle proprioception, visual or vestibular deficits, or hip abductor weakness? Of course, these are not the only potential confounders to postural stability, yet represent some of the considerations of the rehabilitation therapist.

A recent study aimed to further define techniques to measure "time to stabilization" in a double-limb to single-limb stance. The authors measured 15 healthy control subjects and 15 subjects who presented with chronic ankle instability (CAI) and the researchers tested the ability to achieve stability in single-leg stance during eyes open and eyes closed tasks as well as with varied speeds of movement.

The research found that in subjects who had CAI, following transition to single-leg stance, increased postural sway was noted. In the same subjects, when performing the task with eyes closed, those with a history of ankle instability performed the transition much more slowly than those in the control group when allowed to choose their speed of transition. Prior research (described in the linked article) had postulated that time to stabilization (TTS) following double-limb to single-limb transition was an important variable to measure, yet this research did not find that the TTS was significantly different between the groups studied.

This research highlights the value of considering the total limb and trunk stability during testing of functional tasks, as well as considering visual assist versus eyes closed variables for task completion. The speed of task performance should also vary so that deficits can be perceived by the examiner. The authors of this research propose further specifications to future research that will add to the meaningfulness and accuracy of the described testing methods. They also conclude that in patients with chronic ankle instability, an altered and poorer strategy is used in the overcoming of a postural perturbation. If you would like to further explore the sacroiliac joint examination, evaluation and treatment, and discuss concepts of stability, join Institute faculty member Peter Philip at the continuing education course Sacroiliac Joint Treatment this July in Baltimore!

One of the challenges in assessing pelvic muscle function in women who have pain is to avoid triggering pain with the assessment tool. This challenge was met by the use of external measuring of pelvic floor muscles using transperineal four-dimensional (4D) ultrasound in this study by Morin and colleagues. Women who were asymptomatic (n=51) and symptomatic (n=49) were assessed with 4D ultrasound in supine with pelvic floor muscles (PFM) at rest and at maximal contraction. The women who were symptomatic were diagnosed with provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) and all of the women in the study were nulliparous. The data collected using the 4D transperineal US included anorectal angle, levator plate angle, displacement of the bladder neck, and levator hiatus.

Results of the study indicated that women with provoked vestibulodynia had a significantly smaller hiatus, smaller anorectal angle, and at rest, a larger levator plate angle. These differences suggested an increase in pelvic floor muscle tone. Additionally, when the PFM were assessed at maximal contraction, subjects with PVD demonstrated smaller changes in levator hiatus narrowing were noted, with decreased displacement of the bladder neck and decreased changes in levator plate and anorectal angles. These changes are believed to demonstrate pelvic floor muscle weakness.

The authors describe the value of the assessment technique, 4D ultrasonography, as having terrific advantage over other research methods due to the lack of required insertion of the US. While pelvic rehabilitation providers may concur that increased pelvic floor muscle tone in association with pelvic muscle weakness is a common clinical finding, research that describes the phenomenon is needed and much appreciated. We continue to find answers in research such as this article that answers the fundamental question: do women who present with pelvic dysfunction demonstrate differences in pelvic muscle health than a pelvic-healthy population? If you would like to learn more about provoked vestibulodynia including evaluation and management, join faculty member Dee Hartmann at the Assessing and Treating Women with Vulvodynia continuing education course. We are currently confirming dates for this course, and if you would like to host the Vulvodynia course, contact us at the Institute!

Surgery for prostate cancer can impair urinary function, and in the case of persistent urinary incontinence, patients may progress to surgical interventions. In order for physicians to conduct optimal patient counseling and surgical candidate selection for post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence (UI), the records of 95 patients were reviewed in this study. The patients were retrospectively placed into "ideal", n = 72, or "non-ideal", n = 23, categories based on chosen characteristics, and the results of their outcomes and satisfaction were consolidated. Men in the "ideal" group had the following characteristics: mild to moderate UI, external urethral sphincter that appeared intact on cystoscopy, no prior history of pelvic radiation or cryotherapy, no previous UI surgeries, volitional detrusor contraction with emptying of the bladder, and a post-void residual of < 100 mL. Patients who did not meet all listed criteria for the "ideal" group were placed into the "non-ideal" classification.

A cure for the surgery was considered total resolution of post-prostatectomy incontinence with the sling. Of the patients fitting into the ideal classification, 50% reported cure, and of the non-ideal group, 22% reported a cure. Satisfaction rates within the ideal group for the procedure were 92%, whereas the non-ideal group reported a 30% satisfaction. Although uncommon, complications occurring in both groups included prolonged pelvic pain and worsened urinary incontinence. The authors describe the importance of placing the correct amount of tension through the sling, and of leaving as much of the external urethral sphincter in place as possible. Another complication that occurred more frequently is that of acute urinary retention. In the ideal cohort, the 11 cases of urinary retention resolved within 6 weeks of surgery. Of interest is that 12 of the 23 men in the "non-ideal" category had to undergo further surgery with an artificial urethral sphincter.

This information can assist surgeons in guiding and advising patients about operative procedures for post-prostatectomy incontinence. (Ideally, every patient would "fail" a trial of pelvic rehabilitation prior to progressing to a surgery!) If a patient wishes to proceed with a sling surgery despite being in a "non-ideal" category, he could be advised of the known potential outcomes. This article offers support for pre-operative investigation techniques such as urodynamics. Our role as pelvic rehabilitation providers may allow us to discuss such research with patients and providers, and participate in discussions about the role of rehabilitation pre-operatively or post-operatively. If you would like to learn more about working with men who have pelvic floor dysfunctions, you still have time to book a flight to Orlando for the Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction, & Treatment course, where you can learn about male pelvic pain, incontinence and BPH, and male sexual dysfunction. This is the last opportunity to take this course this year!