Perhaps you have seen the Facebook post by Alan Naughton (March 5, 2015) where a horse with one zebra leg tells another horse, “I can’t say I’m entirely pleased with my hip replacement.” Although this post makes some people laugh, I imagine surgical candidates cringe at the thought of complications. Few people hop onto a surgeon’s schedule with great enthusiasm. While hip replacements are sometimes inevitable for quality of life, other hip pathologies can be successfully treated with more conservative measures.

A case report in Manual Therapy (Lewis, Khuu, & Marinko 2015) described how postural correction and alternation of movement patterns were able to reduce hip pain secondary to acetabular dysplasia. A 31-year old female acute care nurse developed anterior hip pain with no trauma, and acetabular dysplasia as well as a labral tear were found. She got temporary relief of her constant ache and occasional sharp, intense pain from an intra-articular injection of cortisone. Her functional complaint was the pain prevented her from returning to recreational running. Intervention involved correcting the subject’s slight hip and knee hyperextension and posterior pelvic tilt with swayback posture, cueing her to walk on the treadmill with slight anterior pelvic tilt and contraction of the abdominals. This decreased her pain while walking from 6/10 to 2/10. Correction of the swayback posture decreased the hip flexion moment, decreasing stress on the anterior hip. At three months and then one year after the initial visit, she was relatively pain free. She still had pain with running, so she was advised to decrease her stride length and take shorter steps as well as decrease her hip extension by pushing off her feet more to minimize anterior hip joint reaction forces. With these cues, she was able to run without pain. Luckily for her, she had declined the option of acetabular reorientation surgery.

A case report in Manual Therapy (Lewis, Khuu, & Marinko 2015) described how postural correction and alternation of movement patterns were able to reduce hip pain secondary to acetabular dysplasia. A 31-year old female acute care nurse developed anterior hip pain with no trauma, and acetabular dysplasia as well as a labral tear were found. She got temporary relief of her constant ache and occasional sharp, intense pain from an intra-articular injection of cortisone. Her functional complaint was the pain prevented her from returning to recreational running. Intervention involved correcting the subject’s slight hip and knee hyperextension and posterior pelvic tilt with swayback posture, cueing her to walk on the treadmill with slight anterior pelvic tilt and contraction of the abdominals. This decreased her pain while walking from 6/10 to 2/10. Correction of the swayback posture decreased the hip flexion moment, decreasing stress on the anterior hip. At three months and then one year after the initial visit, she was relatively pain free. She still had pain with running, so she was advised to decrease her stride length and take shorter steps as well as decrease her hip extension by pushing off her feet more to minimize anterior hip joint reaction forces. With these cues, she was able to run without pain. Luckily for her, she had declined the option of acetabular reorientation surgery.

MacIntyre et al., (2015) presented a case study on conservative management of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) in a retired 22 year old elite ice hockey goaltender. A 4-year history of left anterior hip pain forced him into early retirement. He was diagnosed with longitudinal acetabular labral tears with a cam-type FAI. Before considering surgery, he had to undergo physical therapy, which he did 1-2 times per week for 6 weeks. Treatment consisted of Active Release Technique (ART)® and soft tissue therapy with tools directed to the affected gluteal , iliopsoas, and adductor muscles and fascial planes, spinal manipulation of the right sacroiliac joint, left hip capsule distraction/release using the Mulligan concept, contemporary medical electroacupuncture, and extensive rehabilitation exercises for lumbopelvic stability. After 8 visits, he had no pain at rest or with exercise. At 8 weeks he returned to playing ice hockey and now plays competitively again with no need for surgery.

I would venture to guess no one who takes the conservative route for treatment of hip dysfunction comes out of physical therapy with irreconcilable side effects. Being able to skip surgery using manual therapy and postural correction is a huge goal. If you doubt you can treat the hip effectively, taking Manual Therapy for the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip Complex can not only enhance your manual therapy approach to treatment but also introduce you to an exciting visual feedback system to maximize efficacy of core stabilization exercises.

Lewis, C. L., Khuu, A., & Marinko, L. (2015). Postural correction reduces hip pain in adult with acetabular dysplasia: a case report. Manual Therapy, 20(3), 508–512. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2015.01.014 MacIntyre, K., Gomes, B., MacKenzie, S., & D’Angelo, K. (2015). Conservative management of an elite ice hockey goaltender with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI): a case report. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 59(4), 398–409.

When I bring up the topic of pelvic floor dysfunction in athletes, stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is usually the first aspect of pelvic health that springs to mind – and rightly so, as professional sport is one of the risk factors for stress urinary incontinence Poswiata et al 2014. The majority of studies show that the average prevalence of urinary incontinence across all sports is 50%, with SUI being the most common lower urinary tract symptom. Athletes are constantly subject to repeated sudden & considerable rises in intra-abdominal pressure: e.g. heel striking, jumping, landing, dismounting and racquet loading.

What’s less often discussed is the topic of gastrointestinal dysfunction in athletes. Anal incontinence in athletes is not well documented, although a study from Vitton et al in 2011 found a higher prevalence than in age matched controls (conversely a study by Bo & Braekken in 2007 found no incidence). More recently, Nygaard reported earlier this year (2016) that young women participating in high-intensity activity are more likely to report anal incontinence than less active women.

A presentation by Colleen Fitzgerald, MD at the American Urogynecologic Society meeting in 2014 highlighted the multifaceted nature of pelvic floor dysfunction in female athletes, specifically in this case, triathletes. The study found that one in three female triathletes suffers from a pelvic floor disorder such as urinary incontinence, bowel incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. One in four had one component of the "female athlete triad", a condition characterized by decreased energy, menstrual irregularities and abnormal bone density from excessive exercise and inadequate nutrition. Researchers surveyed 311 women for this study with a median age range of 35 – 44. These women were involved with triathlete groups and most (82 percent) were training for a triathlon at the time of the survey. On average, survey participants ran 3.7 days a week, biked 2.9 days a week and swam 2.4 days a week.

Of those who reported pelvic floor disorder symptoms, 16% had urgency urinary incontinence, 37.4% had stress urinary incontinence, 28% had bowel incontinence and 5% had pelvic organ prolapse. Training mileage and intensity were not associated with pelvic floor disorder symptoms. 22% of those surveyed screened positive for disordered eating, 24% had menstrual irregularities and 29% demonstrated abnormal bone strength. With direct access becoming a reality for many of us, we must acknowledge the need for specific questioning when it comes to pelvic health issues, as well as the ability to recognise signs and symptoms of the female athlete triad in our patients.

Want to learn more about pelvic health for athletes? Join me in beautiful Arlington this November 5-6 at The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor!

J Hum Kinet. 2014 Dec 9; 44: 91–96 Published online 2014 Dec 30. doi:10.2478/hukin-2014-0114 PMCID: PMC4327384. Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence in Elite Female Endurance Athlete Anna Poświata, Teresa Socha and Józef Opara1

J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011 May;20(5):757-63. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2454. Epub 2011 Apr 18. Impact of high-level sport practice on anal incontinence in a healthy young female population. Vitton V, Baumstarck-Barrau K, Brardjanian S, Caballe I, Bouvier M, Grimaud JC.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;214(2):164-71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.067. Epub 2015 Sep 6. Physical activity and the pelvic floor. Nygaard IE, Shaw JM.

Since the passing of Title IX in 1972, which protects people from sex discrimination in education or activity programs receiving federal funding, the number of females participating in sports has greatly increased. The National Federation of State High School Associations states that in 2011 nearly 3.2 million girls are participating in high school sports.

Unfortunately, a consequence of this increased participation in sports is a higher prevalence in urinary incontinence (UI) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in female athletes. Borin et al looked at the ability of nulliparous female athletes to generate intracavity perineal pressure in comparison to nonathletic women. The study demonstrated that higher mean pressures were generated by nonathletic women in comparison to the athletic women group and that lower perineal pressures in the athletic women were also related to number of games per year and time spent on sport specific workouts and strength training workouts.

UI and SUI are underreported in the general population and also in the athletic population. As health care professionals it is important to screen for UI and SUI in our clients. Physical therapy interventions using pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation have shown to decrease the severity of UI and SUI (Rivalta et al, Hulme). Rivalta used internal methods to improve the function of the pelvic floor muscle. Hulme’s success was achieved through activation of the pelvic floor muscles’ extrinsic synergists.

|

|

Pilates is often used in physical therapy as a therapeutic tool to improve lumbar stability with studies showing increases in abdominal strength (Sekendiz), trunk extensor endurance (Sekendiz) and to improve posture (Kloubec). Pilates is often also used in pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation and can easily be modified for low level clients. For example the use of resistance can assist supporting the weight of the leg. Practical proof, while lying supine in neutral lumbar spine position, stretch an arm and a leg away from center, notice the difficulty to maintain neutral spine. Now hold a resistance strap, which is also attached to the foot, and notice how maintaining neutral lumbar spine is easier to maintain (pictured above).

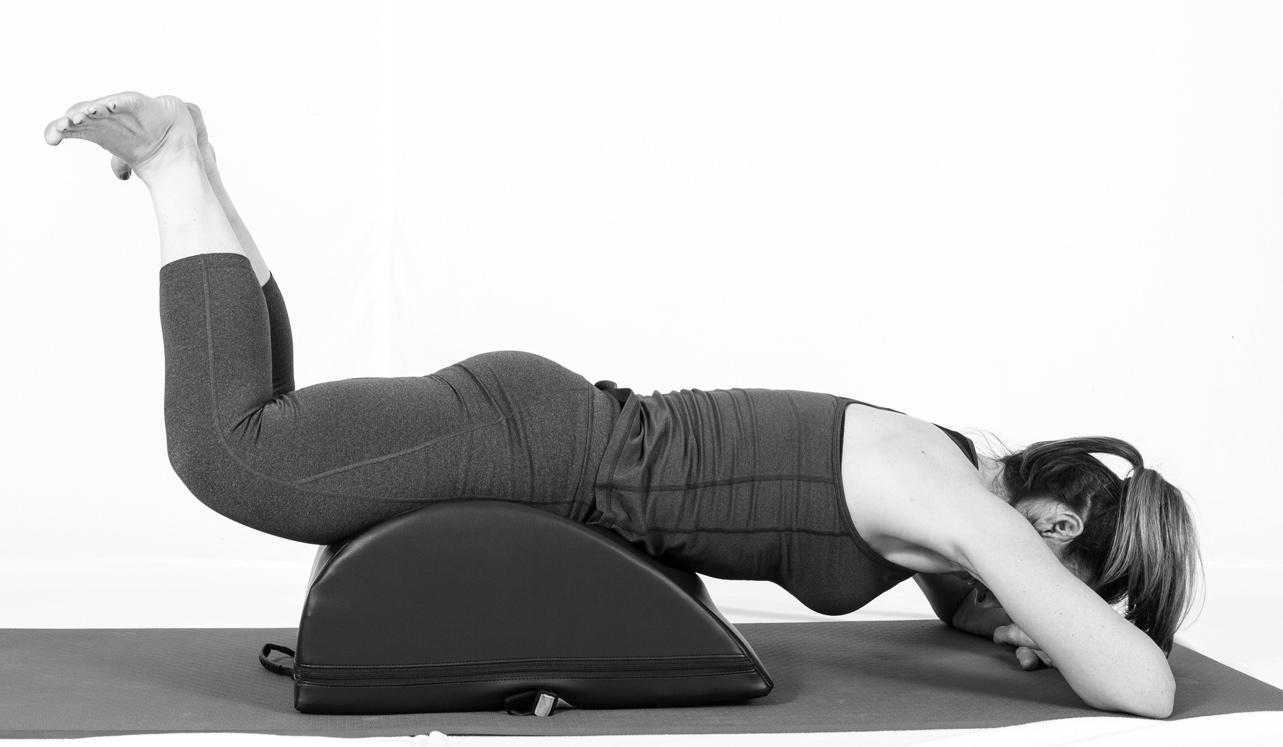

Pilates can also be modified for the higher level client or more athletic client. The use of arc barrels, BOSUs or the Hooked on Pilates MINIMAX (pictured belowy) allow the athletic client to achieve an inverted position, unloading the pelvic floor muscles. In the inverted position, pelvic floor muscles may be activated as intrinsic and/or extrinsic synergists of the pelvic floor muscles are also activated. These types of exercises may be more appealing to the athletic client ensuring continuation of the exercise post discharge from physical therapy.

|

|

Borin LC, Nunes FR, Guirro EC. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle pressure in female athletes. PMR. 2013; 5(3):189-193.

Hulme, Janet. Beyond Kegels 3rd edition, 2012 Phoenix Publishing Co. Missoula, Montana

Kloubec JA. Pilates for improvement of muscle endurance, flexibility, balance and posture. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:661-667.

Rivalta M, Sughunolfi MC, Micali S, De Stafani S, Torcasio F, Bianchi G, Urinary incontinence and sport. First and preliminary experience with a combined pelvic floor rehabilitation program in three female athletes. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(5);330-334.

Sekendiz B, Altun O, Korkusuv F, Akin S, Effects of pilates exercise on trunk strength, endurance and flexibility in sedentary adult females. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2005;9:52-57.

Exercise in pregnancy is a loaded topic. We commonly see images of women doing vigorous exercise in late pregnancy accompanied by judgmental statements about the safety of such activity not only for the woman, but also for the baby. Many myths persist about exercise in pregnancy, and it’s our role as health care specialists to educate women about what is known about exercising. Holly Herman, co-founder of the Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute, has been educating providers about this topic for most of her career. Anyone lucky enough to take a course on pregnancy and postpartum issues from Holly Herman knows that her style of teaching is effective and her passion is contagious. From Holly’s use of patient stories to wonderful humor, you can really “get it” when it comes to clinical concepts and strategies. One of Holly’s clinical pearls that really stuck with me after learning about exercise and pregnancy is the research completed by James Clapp in his book “Exercise in Pregnancy”. In short, the book dispels the myth that women shouldn’t exercise in pregnancy and in fact reports on the benefits of exercise to both Mom and baby for labor, delivery, and beyond. In signature style, Holly held this book up in front of the class and to great laughter said, “And this is the book you should buy for your mother-in-law.”

Another myth that has been perpetuated in relation to pregnancy, labor and delivery is the notion that exercising can make the pelvic floor muscles short, tight, and more narrow, making delivery more difficult. In an article we reported on previously about women being “too tight to give birth” the authors concluded that strong pelvic floor muscles do not lead to challenges with birthing. (Bo et al., 2013) In a more recent article that addressed this issue, Kari Bo and colleagues studied 274 women for levator hiatus (LH) width to see if exercising in late pregnancy did in fact narrow this space. At week 37 of gestation, the exercisers were measured to have a significantly larger LH than the non-exercisers. (Exercisers were defined as women who exercised 30 minutes or more 3 times per week versus the non-exercisers.) The authors conclude that there were not any significant differences in labor outcomes or in delivery outcomes between the groups. (Bo et al., 2015)

Another myth that has been perpetuated in relation to pregnancy, labor and delivery is the notion that exercising can make the pelvic floor muscles short, tight, and more narrow, making delivery more difficult. In an article we reported on previously about women being “too tight to give birth” the authors concluded that strong pelvic floor muscles do not lead to challenges with birthing. (Bo et al., 2013) In a more recent article that addressed this issue, Kari Bo and colleagues studied 274 women for levator hiatus (LH) width to see if exercising in late pregnancy did in fact narrow this space. At week 37 of gestation, the exercisers were measured to have a significantly larger LH than the non-exercisers. (Exercisers were defined as women who exercised 30 minutes or more 3 times per week versus the non-exercisers.) The authors conclude that there were not any significant differences in labor outcomes or in delivery outcomes between the groups. (Bo et al., 2015)

Without a doubt, the patient’s obstetrician gives primary direction to the patient when any high-risk issues are present. Most women however, are basing their exercise choices on experience, on misinformation, myths, or popular opinion. It is our responsibility to engage women in conversations about her health, wellness, and fitness, and to appropriately counsel on exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Most of us lacked proper education about this important population in our primary graduate training, and therefore must seek out information to fill in the gaps. If you are interested in filling in any gaps, join us at one of our peripartum courses around the country. Your next opportunities to take these courses are:

Care of the Postpartum Patient - Seattle, WA

Mar 12, 2016 - Mar 13, 2016

Care of the Pregnant Patient - Somerset, NJ

Apr 30, 2016 - May 1, 2016

Care of the Pregnant Patient - Akron, OH

Sep 10, 2016 - Sep 11, 2016

Bø, K., Hilde, G., Jensen, J. S., Siafarikas, F., & Engh, M. E. (2013). Too tight to give birth? Assessment of pelvic floor muscle function in 277 nulliparous pregnant women. International urogynecology journal, 24(12), 2065-2070.

Bø, K., Hilde, G., Stær-Jensen, J., Siafarikas, F., Tennfjord, M. K., & Engh, M. E. (2015). Does general exercise training before and during pregnancy influence the pelvic floor “opening” and delivery outcome? A 3D/4D ultrasound study following nulliparous pregnant women from mid-pregnancy to childbirth. British journal of sports medicine, 49(3), 196-199.

Clapp, J. F., Cram, C. (2012) Exercising Through Your Pregnancy. Addicts Books

A few years ago, I was convinced my left hip pain was due to osteoarthritis. When my hip locked up after a 14 mile run, my manual therapist husband differentially diagnosed the pain as discogenic. Partly in denial and partly wanting to know the extent of the “damage,” I got an x-ray of my left hip, which was completely normal, and a lumbar MRI, which wasn't pretty. The source of my hip pain was a disc bulge at L3-4 and L4-5 with a Schmorl's node at L5-S1 to boot. Instead of riding the train of thought that we treat what hurts, therapists need to disembark and look further for the source, as suggested in the course, “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain.”

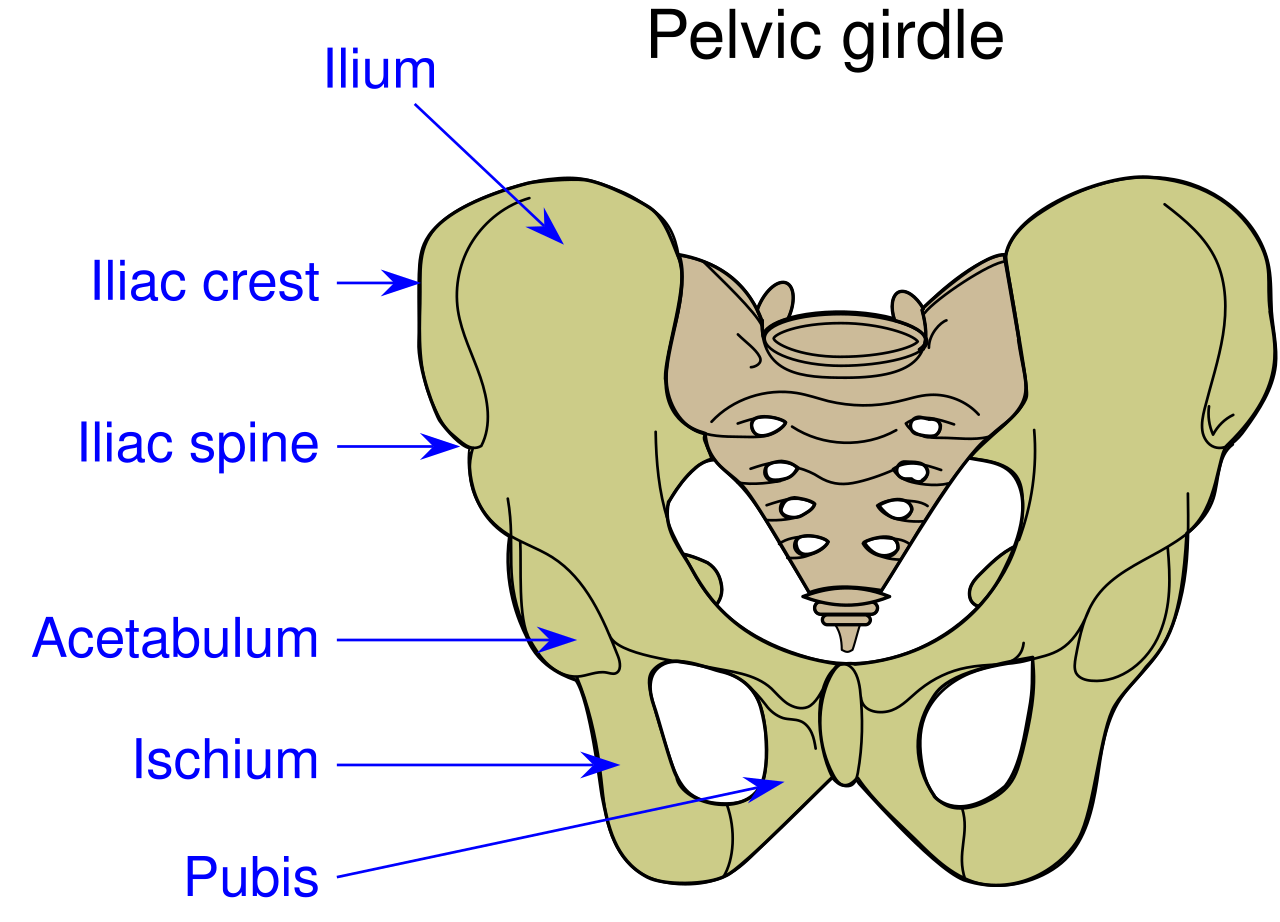

A case report published in the International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy by Livingston, Deprey, and Hensley (2015) documents the discovery of a deeper problem than the referring diagnosis of greater trochanteric pain syndrome. A 29 year old female had to stop running because of lateral hip pain that began 3 months after increasing the intensity and frequency of her running and low impact plyometrics. She had pain in sitting and while running. During the evaluation, she demonstrated a positive Trendelenburg, weak and painless hip abductors, and a positive single leg hop test on concrete. When the pain was not elicited with single leg hop on a foam surface, the patient was referred back to the physician for magnetic resonance imaging. The patient was later diagnosed with an acetabular stress fracture. The therapist’s thorough examination helped prevent possible avascular necrosis or a more traumatic fracture of the pelvis.

A case report published in the International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy by Livingston, Deprey, and Hensley (2015) documents the discovery of a deeper problem than the referring diagnosis of greater trochanteric pain syndrome. A 29 year old female had to stop running because of lateral hip pain that began 3 months after increasing the intensity and frequency of her running and low impact plyometrics. She had pain in sitting and while running. During the evaluation, she demonstrated a positive Trendelenburg, weak and painless hip abductors, and a positive single leg hop test on concrete. When the pain was not elicited with single leg hop on a foam surface, the patient was referred back to the physician for magnetic resonance imaging. The patient was later diagnosed with an acetabular stress fracture. The therapist’s thorough examination helped prevent possible avascular necrosis or a more traumatic fracture of the pelvis.

In a 2013 issue of the same journal, Podschum et al. presents a case report on deciphering the diagnosis in a female runner with deep gluteal pain with pelvic involvement. A 45 year old female marathon runner reported pulling her hamstring and complained of left ischial tuberosity pain with aching into the gluteal and pubic ramus regions that eventually forced her to stop running. She had pain in sitting and could not tolerate speed work. She had a history of low back and pelvic floor pain, with an MRI showing osteitis pubis, a lateral L3-4 bulge, and facet hypertrophy at L4-5. The physical therapist ruled out lumbar disc lesion, radiculopathy, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, and hip labral tear with special tests. Initial treatment focused on the differential diagnoses of hamstring syndrome and ischiogluteal bursitis based on subjective complaints and objective findings. After 4 visits, her deep ache shifted to the inferior pubic ramus in sitting as the ischial tuberosity pain diminished. A trained therapist then conducted a thorough pelvic floor exam. Pelvic floor hypertonic dysfunction was diagnosed and took over the “driver’s seat” as the focus for the rest of the treatment of this patient. Symptoms resolved and the patient returned to running marathons without any of her initial presenting symptoms.

If we let specific pain complaints guide our treatment, we will run out of steam with the lack of progress. Finding the true source of symptoms is critical in physical therapy. Sometimes so much is going on with our patients we have to sort through the weeds before we can access the actual road to recovery. The lumbar spine, hips, and pelvic floor create an intricate map of U-turns and two-way streets, so we need to deepen our understanding of how to navigate the regions. Only then will be able to confidently diagnose the “driver” and let the other areas call “shotgun.”

References:

Livingston, J. I., Deprey, S. M., & Hensley, C. P. (2015). DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS AND CLINICAL DECISION MAKING IN A YOUNG ADULT FEMALE WITH LATERAL HIP PAIN: A CASE REPORT. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 10(5), 712–722.

Podschun, L., Hanney, W. J., Kolber, M. J., Garcia, A., & Rothschild, C. E. (2013). DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DEEP GLUTEAL PAIN IN A FEMALE RUNNER WITH PELVIC INVOLVEMENT: A CASE REPORT. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 8(4), 462–471.

A US study published in the International Society for Sexual Medicine last year reports on the available evidence linking cycling to female sexual dysfunction. In the article, some of the study results are summarized in the left column of the chart below. On the right side of the column, we can consider ideas about how to potentially address these issues.

| Examples of Research Cited |

Ideas for Addressing Potential for Harm |

| dropped handlebar position increases pressure on the perineum and can decrease genital sensation | encourage cyclists to take breaks from dropped position, either by standing up or by moving out of drops temporarily |

| chronic trauma can cause clitoral injury | encourage cyclists to wear appropriately padded clothing, to apply cooling to decrease inflammation, and to use quality shocks or move out of the saddle when going over rough roads/terrain when able |

| saddle loading differs between men and women | women should consider specific fit for bike saddles |

| women have greater anterior pelvic tilt motion | is pelvic motion on bike demonstrating adequate stability of pelvis or is there a lot of extra motion and rocking occurring? |

| lymphatics can be harmed from frequent infections and from groin compression | patients should be instructed in positions of relief from compression and in self-lymphatic drainage |

| pressure in the perineal area is affected by saddle design, shape | female cyclists with concerns about perineal health should work with a therapist or bike expert who is knowledgeable about a variety of products and fit issues |

| unilateral vulvar enlargement can occur from biomechanics factors | therapists should evaluate vulvar area for size, swelling, and evidence of imbalances in the tissues from side to side, and evaluate bike fit and mechanics, encouraging women to create more symmetry of limb use |

| genital sensation is frequently affected in cyclists, indicating dysfunction in pudendal nerve | therapists should evaluate female cyclists for sensory or motor loss, establishing a baseline for re-evaluation |

Because women tend to be more comfortable in an upright position, the authors recommend that a recreational (more upright) versus a competitive (more aerodynamic and forward leaning) position may be helpful for women when appropriate. Although saddles with nose cut-outs and other adaptations such as gel padding in seats are discussed in the article, the authors caution against making any distinct recommendations due to the paucity of literature that is available. The paper concludes that more research is needed, and particularly for considering the varied populations of riders ranging from recreational to racing.

Within a pelvic rehabilitation setting, applying all orthopedic and specific pelvic rehabilitation skills is necessary for women cyclists who present with pelvic dysfunction. Because injury to the perineal area including the pudendal nerve can have negative impact on function such as bowel, bladder, or sexual health, skills in helping a patient heal from compressive or traumatic cycling injuries is very valuable. To learn more about pudendal nerve health and dysfunction, the Institute offers a 2-day course titled Pudendal Neuralgia Assessment, Treatment and Differentials: A Brain/Pain Approach. This course is offered next in Salt Lake City in April, so sign up soon!