How does a male sports and orthopedic physical therapist come to teach about pelvic health and wellness? I was fortunate enough to spend ten years in the NHL as the physical therapist and athletic trainer for the Florida Panthers. Ice hockey is one of the sports that has the highest incidence of groin strains among other pelvic related pathologies.1 As a clinician that was responsible for taking care of the world’s best hockey players, I was challenged to understand the interconnected relationships between the lumbopelvic-hip complex very quickly.

In the early years of my career development and the treatment of mostly males with pelvic pathologies, I leaned heavily on pelvic health professionals to help me understand an area of the body I received little training on in school and even less in my clinical care as a sports and orthopedic manual physical therapist. After years of treating hip and pelvic pathologies on my players I became more comfortable in this enigmatic area of the body. A good friend of mine was on faculty with Herman & Wallace and we frequently would communicate and compare notes. She was treating an increasing number of “sports hernias” (now termed athletic pubalgia or core muscle injury) and was relying on me to help her understand this injury and how to treat it. In turn, she helped me understand what went on in the pelvic health profession and what those therapists were trained to treat and how they went about it.

In the early years of my career development and the treatment of mostly males with pelvic pathologies, I leaned heavily on pelvic health professionals to help me understand an area of the body I received little training on in school and even less in my clinical care as a sports and orthopedic manual physical therapist. After years of treating hip and pelvic pathologies on my players I became more comfortable in this enigmatic area of the body. A good friend of mine was on faculty with Herman & Wallace and we frequently would communicate and compare notes. She was treating an increasing number of “sports hernias” (now termed athletic pubalgia or core muscle injury) and was relying on me to help her understand this injury and how to treat it. In turn, she helped me understand what went on in the pelvic health profession and what those therapists were trained to treat and how they went about it.

This collaboration eventually led to me joining Herman & Wallace and offering a sports and orthopedic perspective to pelvic floor consideration. I have attended Herman & Wallace’s Pelvic Floor courses to fully understand the training that a pelvic health therapist undergoes. Admittedly, I do not perform internal work because I have found a niche helping clinicians such as myself who understand that the pelvic floor is a key variable in human movement and we need to understand it at a much higher level than what we are exposed to in school, but don’t have the career trajectory of becoming an internal practitioner of the pelvic floor.

I have designed the Athletes and Pelvic Rehabilitation course to reach both the sports and orthopedic clinician as well as the pelvic health practitioner who might be a veteran of pelvic floor education and treatment. Both groups will leave this course with additional tools for their clinical tool box in the realms of manual therapy and exercise.2 Here are some of the objectives for the course:

- Provide clinicians that do not perform internal work a better and more complete understanding of how the pelvic floor integrates into human movement, particularly higher-level activities such as running, lifting and all types of sporting movements.

- Provide both the experienced and pelvic floor early learner with a comprehensive paradigm of exercise theory, development and progressions as well as how to provide non-internal manual therapy to influence the performance of the pelvic floor.

- Provide strategies for clinicians to determine when your patient would be better served with a referral to a pelvic health practitioner and what the current evidence is to support your decision.

- Create innovative and engaging therapeutic exercise programs (home exercise programs too!) for your patients directed at the pelvis with specific attention to upright and functional positioning.

What do people who have attended courses with Dr. Dischiavi have to say? Janna wrote the following email to Herman & Wallace about Steve's Course:

"Good morning. I wanted to make sure that you knew what a fantastic clinician you have to join your team in Steve Dischiavi. I am a practicing OB and orthopedic therapist and felt this course was fantastic! Usually the main goal is to come away with a couple of clinical "pearls." I felt as though I came away with a full days worth of "pearls." I really liked that the course was not totally pelvic floor based, however was totally relevant to the women's health population, but it will also apply to the majority of my current patient population as well. Thank you for the opportunity to learn from Steve!"

1. Orchard JW. Men at higher risk of groin injuries in elite team sports: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(12):798-802.

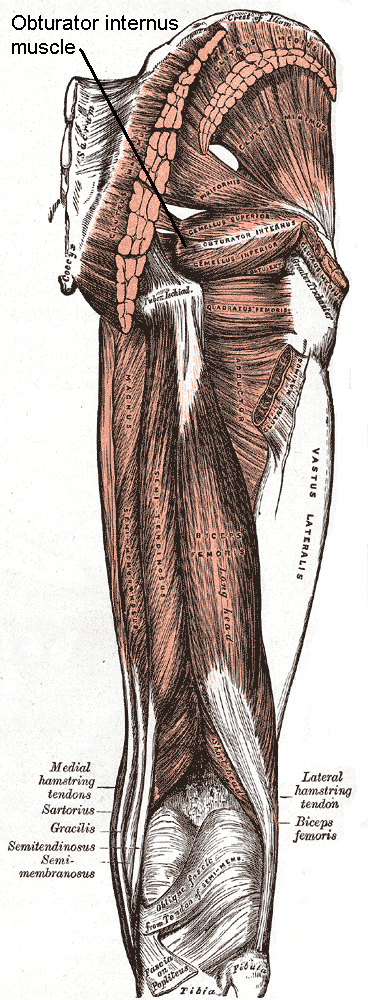

2. Tuttle L. The Role of the Obturator Internus Muscle in Pelvic Floor Function. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2016;40(1):15-19.

Perhaps you have seen the Facebook post by Alan Naughton (March 5, 2015) where a horse with one zebra leg tells another horse, “I can’t say I’m entirely pleased with my hip replacement.” Although this post makes some people laugh, I imagine surgical candidates cringe at the thought of complications. Few people hop onto a surgeon’s schedule with great enthusiasm. While hip replacements are sometimes inevitable for quality of life, other hip pathologies can be successfully treated with more conservative measures.

A case report in Manual Therapy (Lewis, Khuu, & Marinko 2015) described how postural correction and alternation of movement patterns were able to reduce hip pain secondary to acetabular dysplasia. A 31-year old female acute care nurse developed anterior hip pain with no trauma, and acetabular dysplasia as well as a labral tear were found. She got temporary relief of her constant ache and occasional sharp, intense pain from an intra-articular injection of cortisone. Her functional complaint was the pain prevented her from returning to recreational running. Intervention involved correcting the subject’s slight hip and knee hyperextension and posterior pelvic tilt with swayback posture, cueing her to walk on the treadmill with slight anterior pelvic tilt and contraction of the abdominals. This decreased her pain while walking from 6/10 to 2/10. Correction of the swayback posture decreased the hip flexion moment, decreasing stress on the anterior hip. At three months and then one year after the initial visit, she was relatively pain free. She still had pain with running, so she was advised to decrease her stride length and take shorter steps as well as decrease her hip extension by pushing off her feet more to minimize anterior hip joint reaction forces. With these cues, she was able to run without pain. Luckily for her, she had declined the option of acetabular reorientation surgery.

A case report in Manual Therapy (Lewis, Khuu, & Marinko 2015) described how postural correction and alternation of movement patterns were able to reduce hip pain secondary to acetabular dysplasia. A 31-year old female acute care nurse developed anterior hip pain with no trauma, and acetabular dysplasia as well as a labral tear were found. She got temporary relief of her constant ache and occasional sharp, intense pain from an intra-articular injection of cortisone. Her functional complaint was the pain prevented her from returning to recreational running. Intervention involved correcting the subject’s slight hip and knee hyperextension and posterior pelvic tilt with swayback posture, cueing her to walk on the treadmill with slight anterior pelvic tilt and contraction of the abdominals. This decreased her pain while walking from 6/10 to 2/10. Correction of the swayback posture decreased the hip flexion moment, decreasing stress on the anterior hip. At three months and then one year after the initial visit, she was relatively pain free. She still had pain with running, so she was advised to decrease her stride length and take shorter steps as well as decrease her hip extension by pushing off her feet more to minimize anterior hip joint reaction forces. With these cues, she was able to run without pain. Luckily for her, she had declined the option of acetabular reorientation surgery.

MacIntyre et al., (2015) presented a case study on conservative management of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) in a retired 22 year old elite ice hockey goaltender. A 4-year history of left anterior hip pain forced him into early retirement. He was diagnosed with longitudinal acetabular labral tears with a cam-type FAI. Before considering surgery, he had to undergo physical therapy, which he did 1-2 times per week for 6 weeks. Treatment consisted of Active Release Technique (ART)® and soft tissue therapy with tools directed to the affected gluteal , iliopsoas, and adductor muscles and fascial planes, spinal manipulation of the right sacroiliac joint, left hip capsule distraction/release using the Mulligan concept, contemporary medical electroacupuncture, and extensive rehabilitation exercises for lumbopelvic stability. After 8 visits, he had no pain at rest or with exercise. At 8 weeks he returned to playing ice hockey and now plays competitively again with no need for surgery.

I would venture to guess no one who takes the conservative route for treatment of hip dysfunction comes out of physical therapy with irreconcilable side effects. Being able to skip surgery using manual therapy and postural correction is a huge goal. If you doubt you can treat the hip effectively, taking Manual Therapy for the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip Complex can not only enhance your manual therapy approach to treatment but also introduce you to an exciting visual feedback system to maximize efficacy of core stabilization exercises.

Lewis, C. L., Khuu, A., & Marinko, L. (2015). Postural correction reduces hip pain in adult with acetabular dysplasia: a case report. Manual Therapy, 20(3), 508–512. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2015.01.014 MacIntyre, K., Gomes, B., MacKenzie, S., & D’Angelo, K. (2015). Conservative management of an elite ice hockey goaltender with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI): a case report. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 59(4), 398–409.

Dr. Dischiavi is a Herman & Wallace faculty member who authored and teaches Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis: Manual Movement Therapy and the Myofascial Sling System, available this August in Boston, MA.

STEM is an acronym for science, technology, engineering, and math. These fields are deeply intertwined and taking this approach could potentially be a way to facilitate the physical therapist’s appreciation of human movement.

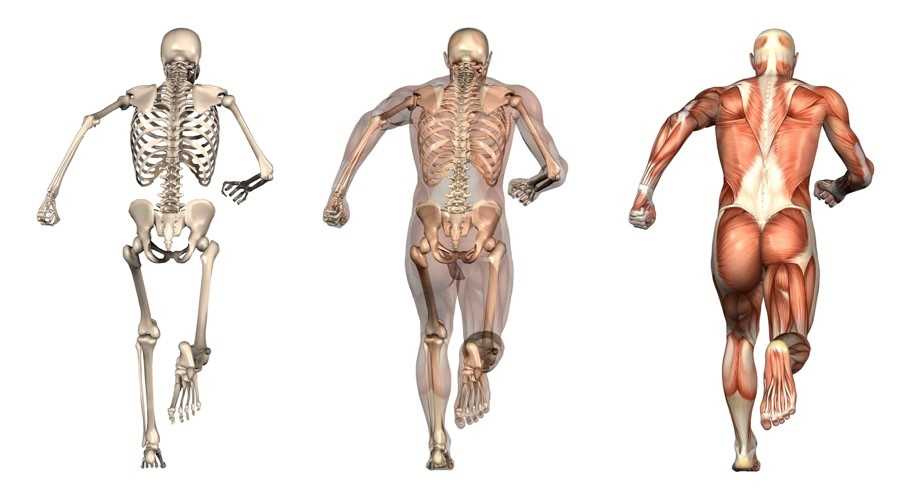

Science: I would bet most physical therapists would agree that science is the cornerstone of our profession. It is time to look across all the landscapes of science to better understand the physical principles that govern movement. Biotensegrity is a great example of how science from a field such as cellular biology can help possibly explain how we maintain an erect posture when the rigid bony structure of our skeleton is only connected from bone to bone by soft tissues [1]. The brain and central nervous system regulates muscle tone, and it is resting muscle tone that give our bodies the ability to be upright. Without resting muscle tone, we would crumple to the ground as a heap of bones within a bag of skin. Since the CNS can either up or down regulate muscle tone, this allows us to create the rigidity we need to accomplish higher level movements such as sport, and then return to a resting state after the movements are performed (see running skeleton picture below). This theory of organismic support was bred within the scientific field of cellular biology, and can potentially be applied effectively to the human organism. As physical therapists, I agree we need to be skeptical of new ideas, but we also need to embrace the idea that the physical sciences have applied to nature for centuries, and it is possible these various scientific fields can help us unlock new ideas and allow us to look at things through a different lens.

Science: I would bet most physical therapists would agree that science is the cornerstone of our profession. It is time to look across all the landscapes of science to better understand the physical principles that govern movement. Biotensegrity is a great example of how science from a field such as cellular biology can help possibly explain how we maintain an erect posture when the rigid bony structure of our skeleton is only connected from bone to bone by soft tissues [1]. The brain and central nervous system regulates muscle tone, and it is resting muscle tone that give our bodies the ability to be upright. Without resting muscle tone, we would crumple to the ground as a heap of bones within a bag of skin. Since the CNS can either up or down regulate muscle tone, this allows us to create the rigidity we need to accomplish higher level movements such as sport, and then return to a resting state after the movements are performed (see running skeleton picture below). This theory of organismic support was bred within the scientific field of cellular biology, and can potentially be applied effectively to the human organism. As physical therapists, I agree we need to be skeptical of new ideas, but we also need to embrace the idea that the physical sciences have applied to nature for centuries, and it is possible these various scientific fields can help us unlock new ideas and allow us to look at things through a different lens.

Technology: As not only a practicing physical therapist, but as a newly appointed assistant professor within a budding physical therapy program it is my duty to embrace evidence based practice. I believe without question, when evidence that is sound exists it should help direct patient care. It is also clear that our tests and measures that are currently being utilized to help develop new evidence are lacking, specifically with regard to human movement and sport performance.

Technology: As not only a practicing physical therapist, but as a newly appointed assistant professor within a budding physical therapy program it is my duty to embrace evidence based practice. I believe without question, when evidence that is sound exists it should help direct patient care. It is also clear that our tests and measures that are currently being utilized to help develop new evidence are lacking, specifically with regard to human movement and sport performance.

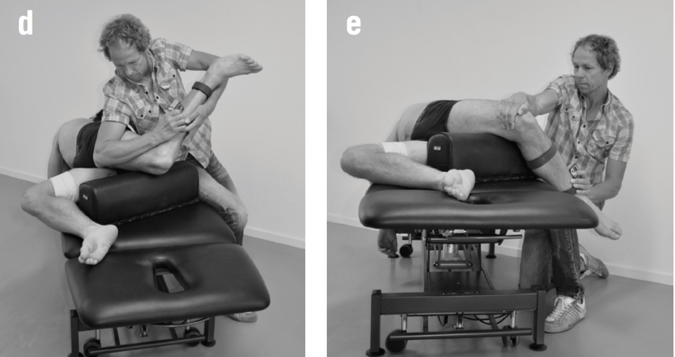

Sports performance is such a complex system (more on this later) we can’t expect to study things such as injury prevention at slow speeds utilizing maneuvers that aren’t even seen in the sport itself. Recently, Bahr [2] suggested that screening for sports injuries is pretty much a futile effort as he titled his article “Why screening tests to predict injury do not work - and probably never will…: a critical review.” Eventually technology will need to be developed that can measure high speed movement across multiple planes and ranges of motion, and essentially capture the complex spiraling that occurs with human movement and the bodies effort to attenuate ground reaction forces. This concept can be illustrated in the current work of Tak and Langhout [3] who have developed a novel approach to measure hip ROM in soccer players. They have essentially performed a thorough needs analysis of the kicking motion and determined that the classical method of measuring hip ROM doesn’t take into account the body’s need to spiral itself to gain the energy in the system needed to kick a ball [Fig 1]. This global understanding of the dynamic integration of the kinetic chain (which is covered in my hip course!) is what has led them to design this new method to measure hip ROM. Now, we will need technological advancements to capture, record, and measure these types of positions across three planes and at high speeds to establish the data that will eventually lead to evidence that will translate into sport. This is a great example of how clinical innovation sometimes precedes actual evidence to support its use. As William Blake was quoted as saying “what is now proven was once only imagined.”

Engineering: Structural engineering should be included in every physical therapy education program. There are many basic structural engineering principles that directly apply to a physical therapists practice. For example, the principal of elastics is frequently discussed within structural engineering. Elastics describes to what extent deformation is proportional to the forces applied to a particular material. In physical therapy muscles are that particular material, muscles must have elasticity and extensibility, not flexibility! In elastics, a rubber band is often used as a simple example to explain this engineering concept.

Engineering: Structural engineering should be included in every physical therapy education program. There are many basic structural engineering principles that directly apply to a physical therapists practice. For example, the principal of elastics is frequently discussed within structural engineering. Elastics describes to what extent deformation is proportional to the forces applied to a particular material. In physical therapy muscles are that particular material, muscles must have elasticity and extensibility, not flexibility! In elastics, a rubber band is often used as a simple example to explain this engineering concept.

A rubber band will elongate and develop potential energy until release and then unleash kinetic energy. Our human movement system relies heavily on the principle of elastics. The rectus femoris is a two-joint muscle across the hip. During gait and running the rectus femoris is elongated as the hip moves into extension, this elongation builds its potential energy until the foot comes off the ground to initiate the swing phase, and the kinetic energy released in the system allows momentum to carry the lower extremity forward.

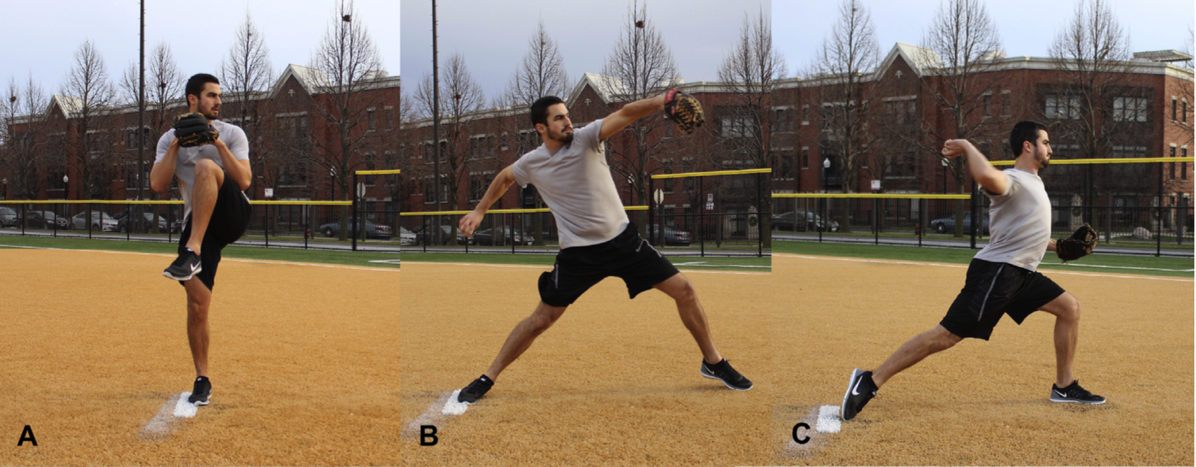

I would add that possibly the twisting created by the contralateral counter trunk rotation and reciprocating arm and leg swing that accompanies the hip extension is what creates tension throughout the entire anterior chain, similar to why Tak and Langhout feel its important to take up all soft tissue slack three dimensionally to effectively measure hip ROM needed for a soccer kick. It is considering that the elasticity in the entire system (organism) is needed to create an efficient human movement, which is kicking a ball in this example. When the body utilizes passive lengthening of muscle chains, as in elastics, it allows the body to move more efficiently. This is described by Chu [4] who reports that in the pitching motion maximizing force development in the large muscles of the core and legs produces more than 51%- 55% of the kinetic energy that is transferred to the hand [Fig 2]. The thoracolumbar fascia is involved in the kinetic chain during throwing activities and connects the lower limbs through the gluteus maximus muscle to the upper limbs through the latissimus dorsi. This idea of a dynamic integration of the kinetic chain is the main concept of the exercise portion of my hip course!

I would add that possibly the twisting created by the contralateral counter trunk rotation and reciprocating arm and leg swing that accompanies the hip extension is what creates tension throughout the entire anterior chain, similar to why Tak and Langhout feel its important to take up all soft tissue slack three dimensionally to effectively measure hip ROM needed for a soccer kick. It is considering that the elasticity in the entire system (organism) is needed to create an efficient human movement, which is kicking a ball in this example. When the body utilizes passive lengthening of muscle chains, as in elastics, it allows the body to move more efficiently. This is described by Chu [4] who reports that in the pitching motion maximizing force development in the large muscles of the core and legs produces more than 51%- 55% of the kinetic energy that is transferred to the hand [Fig 2]. The thoracolumbar fascia is involved in the kinetic chain during throwing activities and connects the lower limbs through the gluteus maximus muscle to the upper limbs through the latissimus dorsi. This idea of a dynamic integration of the kinetic chain is the main concept of the exercise portion of my hip course!

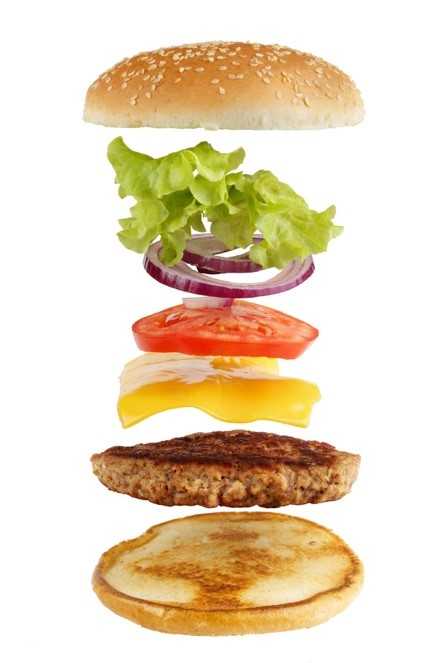

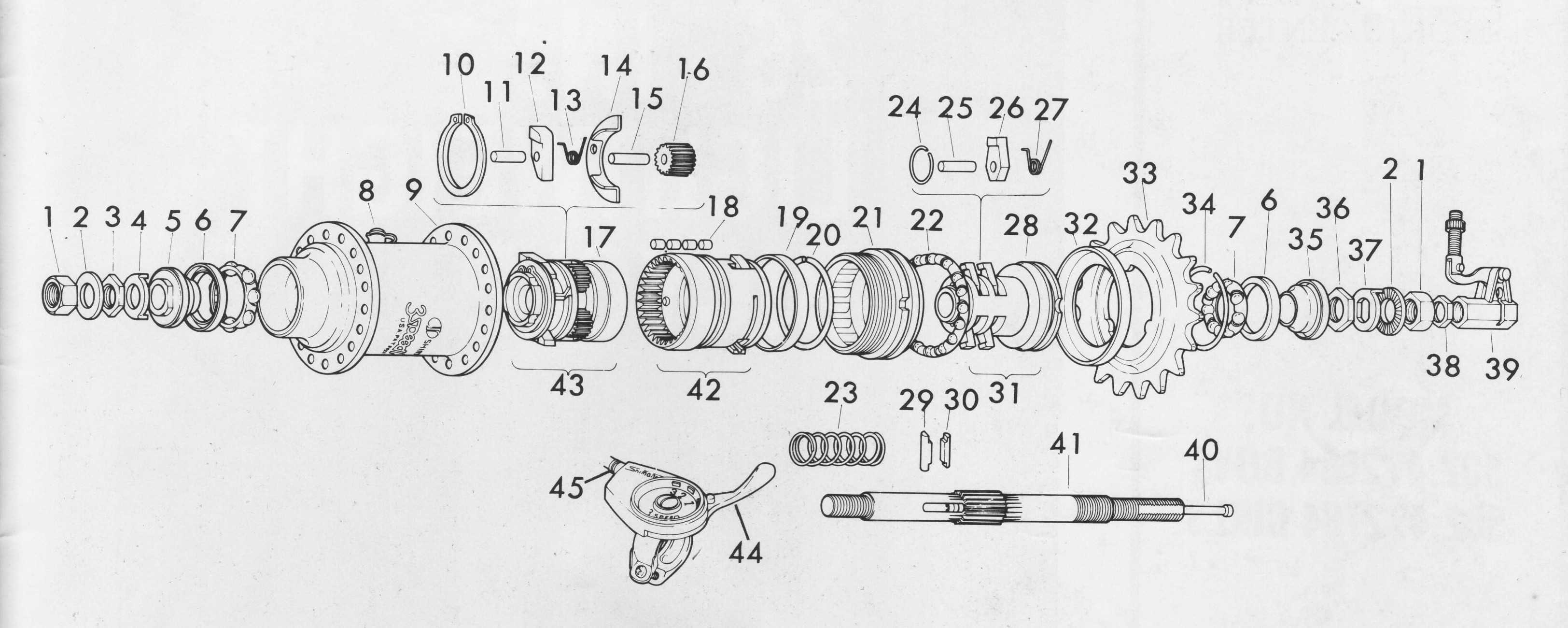

Math: The dynamic systems theory is an area of mathematics that most physical therapists probably don’t consider during everyday treatment. Little do they know, every treatment decision we as therapists make for our patient/clients has some root found in the dynamic systems theory. In fact, it is a fitting description when this theory is applied to human movement. Human movement is an incredibly complex system comprised of many different systems all working at the same time. Paul Glazier recently offered a Grand Unified Theory (GUT) for sports performance [5] and he discusses in detail the various systems and dynamic elements involved in sports performance from musculoskeletal, to neural, to cognitive, environmental, hormonal, and emotional just to name a few. The systems at work during sport when combined are exponential and most likely infinite. This is why it is so difficult to try and capture all these dynamic systems in a laboratory setting with the current technology available. In my hip course offered through Herman & Wallace I offer a novel paradigm to help clinicians construct therapeutic exercise programs using the hip as a cornerstone to human movement. I try to compact these various systems into 8 overlapping elements related to sport performance. When each of these 8 components are “exploded” as you might see in an engineering schematic where an engine is exploded to see all the parts that make the engine or more simply explained using a cheeseburger as the example [Fig 3]. Sure its easy to spot the cheeseburger when its whole just like when you see an athlete on the field running it seems obvious. Once the cheeseburger is “exploded” you can now isolate each sub-element included in your cheeseburger. This cheeseburger example is an obvious over-simplification, but if we exploded the bun to see the underlying grain and the seeds and so on…you now start to get an idea of how deep and intertwined all these subsystems are. Interestingly, the engine and the cheeseburger have finite parts and fit together, the human system has different parts in different systems depending on the sport and who might be playing it, under ever-changing scenery, and so on. So you can now see how the 8 components I outline in my course can house many different aspects of these dynamic systems. Although, I think this is progress with regard to the current state of the evidence, specifically with regard to utilizing the hip during movement, there are other systems at work that clinicians simply cannot control, such as gender, hormonal, environmental, etc…The idea is to try to identify and then manipulate modifiable factors whenever possible. These concepts are more clearly described and implemented in my hip course! Please come and check it out, and let me know what you think!

Math: The dynamic systems theory is an area of mathematics that most physical therapists probably don’t consider during everyday treatment. Little do they know, every treatment decision we as therapists make for our patient/clients has some root found in the dynamic systems theory. In fact, it is a fitting description when this theory is applied to human movement. Human movement is an incredibly complex system comprised of many different systems all working at the same time. Paul Glazier recently offered a Grand Unified Theory (GUT) for sports performance [5] and he discusses in detail the various systems and dynamic elements involved in sports performance from musculoskeletal, to neural, to cognitive, environmental, hormonal, and emotional just to name a few. The systems at work during sport when combined are exponential and most likely infinite. This is why it is so difficult to try and capture all these dynamic systems in a laboratory setting with the current technology available. In my hip course offered through Herman & Wallace I offer a novel paradigm to help clinicians construct therapeutic exercise programs using the hip as a cornerstone to human movement. I try to compact these various systems into 8 overlapping elements related to sport performance. When each of these 8 components are “exploded” as you might see in an engineering schematic where an engine is exploded to see all the parts that make the engine or more simply explained using a cheeseburger as the example [Fig 3]. Sure its easy to spot the cheeseburger when its whole just like when you see an athlete on the field running it seems obvious. Once the cheeseburger is “exploded” you can now isolate each sub-element included in your cheeseburger. This cheeseburger example is an obvious over-simplification, but if we exploded the bun to see the underlying grain and the seeds and so on…you now start to get an idea of how deep and intertwined all these subsystems are. Interestingly, the engine and the cheeseburger have finite parts and fit together, the human system has different parts in different systems depending on the sport and who might be playing it, under ever-changing scenery, and so on. So you can now see how the 8 components I outline in my course can house many different aspects of these dynamic systems. Although, I think this is progress with regard to the current state of the evidence, specifically with regard to utilizing the hip during movement, there are other systems at work that clinicians simply cannot control, such as gender, hormonal, environmental, etc…The idea is to try to identify and then manipulate modifiable factors whenever possible. These concepts are more clearly described and implemented in my hip course! Please come and check it out, and let me know what you think!

I’m hoping the STEM approach can possibly make it into physical therapy curriculums to illustrate to future physical therapists that there are many different disciplines at work with regard to physical therapy, and taking a global view of these elements can certainly be worthwhile.

1. Ingber, D.E., N. Wang, and D. Stamenovic, Tensegrity, cellular biophysics, and the mechanics of living systems. Rep Prog Phys, 2014. 77(4): p. 046603.

2. Bahr, R., Why screening tests to predict injury do not work-and probably never will...: a critical review. Br J Sports Med, 2016.

3. Tak, I., et al., Hip Range of Motion Is Lower in Professional Soccer Players With Hip and Groin Symptoms or Previous Injuries, Independent of Cam Deformities. Am J Sports Med, 2016. 44(3): p. 682-8.

4. Chu, S.K., et al., The Kinetic Chain Revisited: New Concepts on Throwing Mechanics and Injury. PM R, 2016. 8(3 Suppl): p. S69-77.

5. Glazier, P.S., Towards a Grand Unified Theory of sports performance. Hum Mov Sci, 2015.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

The following guest post comes to us from Angie Johnson, a physical therapist with Kaiser Permanente in Portland, OR.

The following guest post comes to us from Angie Johnson, a physical therapist with Kaiser Permanente in Portland, OR.

Did you know that the pelvic floor muscles are actually quite thin? “Pelvic floor muscles are able to produce enough force to overcome changes in intra-abdominal pressure during less rigorous activities of daily living,“ but in activities such as coughing and jumping, “intra-abdominal pressure clearly exceeds the maximum force generated by pelvic floor muscles alone.”1 But we know that people are continent of urine during these activities, so it begs to question what structures help support the pelvic floor during high force events?

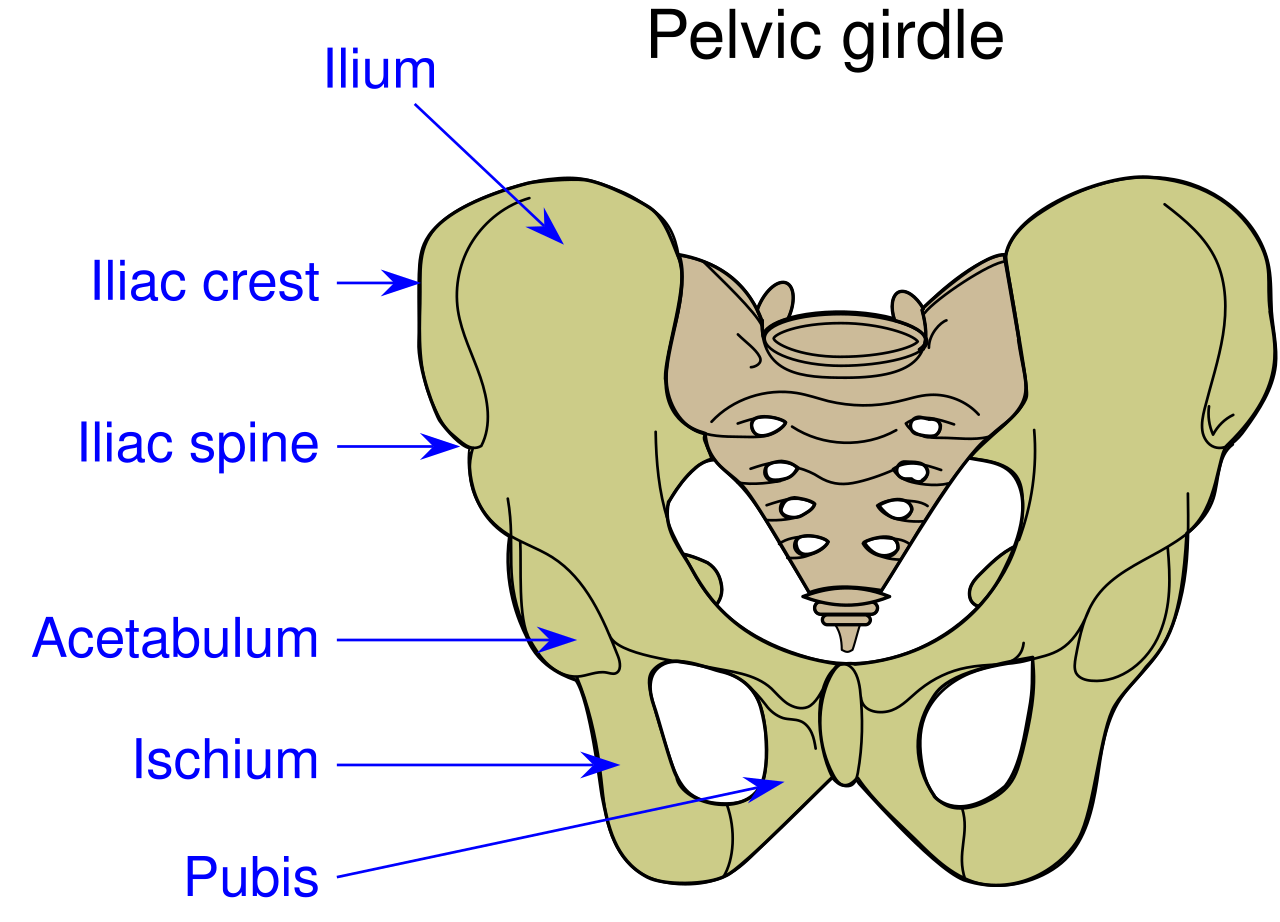

In our journey of pelvic rehabilitation and evidence-based medicine, researchers have determined that contributors to pelvic floor function include trunk stabilization2 and co-contraction of the abdominal wall (especially transverse abdominus)3,4. But this is only the beginning of the story. To add to this picture, new research, recently published in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy (January/April 2016) validates what we as practitioners already know; hip muscles play a crucial role in optimal pelvic floor functioning.

Knowledge of the anatomy of the pelvic floor and hip musculature helps to give us more understanding of the continence mechanism during high force activity. Obturator internus, which can be easily palpated through the vaginal wall “acts to externally rotate the hip. Interesting, this muscle actually shares a fascial attachment with the pelvic floor muscles.”

Researchers from a team at San Diego State University asked the very pertinent question: If you strengthen obturator internus do you strengthen the pelvic floor muscles too? To answer this question, they conducted a randomized control trial of 40 nulliparous women, aged 18-35, who were assigned to a hip exercise or control group. Both hip external rotator strength and pelvic floor muscle strength (via the Peritron™ perineometer) were measured in all of the women. The exercise group was then asked to perform clamshell exercises, isometric wall external rotation and “monster walks” as their specific hip exercises. The prescription of the exercises were 3 sets of 10 repetitions 3 days per week for 12 weeks. One session each week was supervised in the laboratory to ensure proper execution.

After the 12 weeks, the exercise group had an increase in hip external rotation strength, but also in pelvic floor muscle peak pressure. That was without any specific pelvic floor strengthening exercises at all. Strengthen the hips by doing these three exercises, and pelvic floor strength increases!! This is exciting and fantastic news for us as pelvic floor therapists and a good message to convey to our patients.

The results of this study are preliminary, but if you are treating pelvic floor weakness, hip external rotation strengthening exercises in addition to the traditional kegel strengthening exercises are a must. Go ahead – let’s all get hippie!

Tuttle LJ, DeLozier ER, Harter KA et al. The Role of the Obturator Internus Muscle in Pelvic Floor Function. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2016; 40, 1 pg 15-19

Sapsford R. Rehabilitation of pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. Man Ther 2004;9(1):31-42

Sapsford RR, Hodges PW, Ricahrdson CA, Cooper DH, Markwell SJ, Jull GA. Co-activation of the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles during voluntary exercises. Neruourol Urodyn 2001;20(1):3-12

Sapsord RR, Hodges PW. Contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during abdominal maneuvers. Arch Phys Med REhabil. 2001;82(8):1081-1088

Faculty member, Ginger Garner PT, L/ATC, PYT will be giving 2 lectures at this year’s annual Montreal International Symposium for Therapeutic Yoga, or MISTY for short, in Montreal, Quebec. The first is a 2-hour lecture titled, Vocal Liberation, and the second is a 4-hour lecture titled, Hip Preservation: Yoga Reconsidered, Visit http://www.homyogaevents.com to learn more.

Yoga is, unarguably, a popular contemplative science, enjoying 36.7 million practitioners in the US alone, up from 20.4 million in 2012.1 A 16 billion dollar industry, yoga is one of the most widely utilized methods of complementary and integrative medicine in America today. In 2008, the editor of Yoga Journal declared “yoga as medicine” as the next great wave. That was right in the middle of the Great Recession, when the last thing on the collective healthcare industry’s mind was yoga.

Yoga is, unarguably, a popular contemplative science, enjoying 36.7 million practitioners in the US alone, up from 20.4 million in 2012.1 A 16 billion dollar industry, yoga is one of the most widely utilized methods of complementary and integrative medicine in America today. In 2008, the editor of Yoga Journal declared “yoga as medicine” as the next great wave. That was right in the middle of the Great Recession, when the last thing on the collective healthcare industry’s mind was yoga.

What happened during the same time frame as the interest in yoga surged?

Our expanded knowledge of hip anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology exploded onto the medical scene, providing more information than ever about how to address, preserve, and otherwise attend to the hip joint. Prior to this new age of research, the hip was relegated to a joint worthy of no more than a tendonitis, bursitis, or osteoarthritis diagnosis. A person was simply a hip replacement candidate or not. There was no other option once a hip joint had prematurely degenerated. Now, that has all changed, thanks to technological advances in diagnostic testing and investigation.

Yet, the worlds of hip preservation and rehabilitation and yoga have yet to join hands. Many of my patients and colleagues have suffered from unnecessary hip injuries, from labral tears, all types of impingement, and compounding secondary diagnoses such as torn hamstrings, sports hernias, gluteal tendinopathy, to pelvic pain, all due to yoga practice. Some suffered injuries in yoga class during a single traumatic injury, and some injuries were drawn out over years of accumulated microinjury to capsuloligamentous, bony, or cartilaginous structures.

Hip labral injuries (HLI) have vastly increased over the last 10 years, perhaps making HLI the newest orthopaedic diagnosis of the 21st century. This discovery also makes surgical and conservative management of HLI uncharted territory. Conservative therapy includes nonsurgical and post-surgical rehabilitation, and since the average time from injury to diagnosis is 2.5 years, there are many people with hip, pelvic, back, or sacroiliac joint pain that have undiagnosed hip labral tears.

I should make myself quite clear, however. I am not out to demonize yoga or fear-monger the practice of yoga or how it may wreck a person’s body (to use recently controversial language).

My purpose is two-fold: To clarify 1) “what” and “how” yoga can be a safe, effective form or physical therapy and rehabilitation for the hip and pelvis, as well as to 2) underscore the areas where yoga posture practice should be evolved to prevent injury.

To that end, I have written and will be presenting a new 4-hour workshop entitled, Hip Preservation: Yoga Reconsidered, at the Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga (MISTY) this weekend in Canada. The lecture is relevant for yoga teachers, yoga enthusiasts, yoga therapists, and health care professionals who are interested in learning how to prevent hip injury in yoga practice.

The workshop will introduce identification of imbalances that could contribute to HLI, as well as understand the common mistakes made in yoga practice that could increase HLI or hip impingement. Understanding the pain patterns that surround HLI are also critical to safe and therapeutic yoga practice and will be discussed. Discussion of structure, function, ability and “dis”ability of the hip, including their major substrates, will help identify the “red flags” in yoga practice, identifying high risk populations and those who need postural modification(s) and/or outside referral to physical therapy.

I am looking forward to instructing a high energy, action-packed hands-on learning session at MISTY on March 19-20, along with my presenting a 2-hour lecture on maximizing public speaking impact through Vocal Liberation: The Voice as Therapy.

- The Voice as a Linking Science for Clinical and Business Efficacy

- Hip Preservation: Yoga Reconsidered

- Ginger’s lecture overview - Montreal International Symposium for Therapeutic Yoga

Want to learn more?

Bring Ginger’s 16 hour continuing education course, Differential Diagnosis for Hip Labral Injuries to your facility in 2017 through Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

Yoga in America 2016 Survey. Yoga Alliance and Yoga Journal. January 2016.

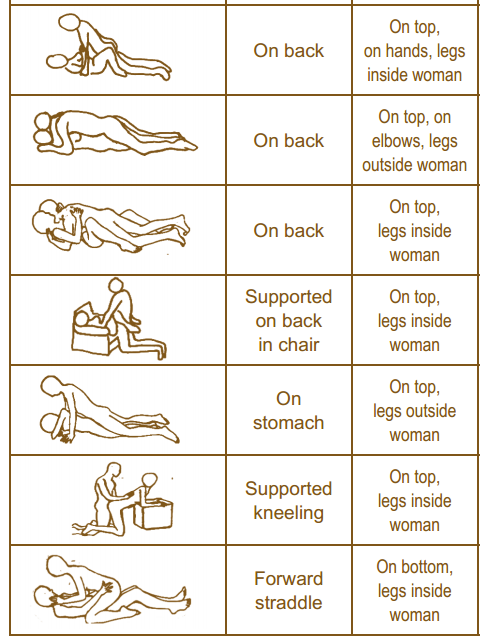

As pelvic rehab providers, we may find it easy to talk to our patients about sexual function when it is a patient who comes to us with a sexually relevant problem or directly related diagnosis, such as dyspareunia or limited intercourse participation due to prolapse symptoms. However, are we talking to our other patients about sexual function? Are they talking to us about it? What about our orthopedic patients - are we routinely asking them about how their problem can affect their sexual function? Some recent studies found that 32% of patients planning to undergo a Total Hip Replacement (THR) had reported concerns about difficulties with sexual activityBaldursson, Wright. Was the fact that they could not participate in sexual activity due to the hip pain a driving factor when considering the hip replacement, maybe? Just because a patient doesn’t ask, does not mean that they don’t want to know how their orthopedic injury affects sexual function. Resuming sexual function is an important quality of life goal that is included on few outcome assessment forms, however, there are some that address this subject such as the Oswestry Disability Index for Low Back Pain. Discussion of this topic should be addressed more routinely than it is.

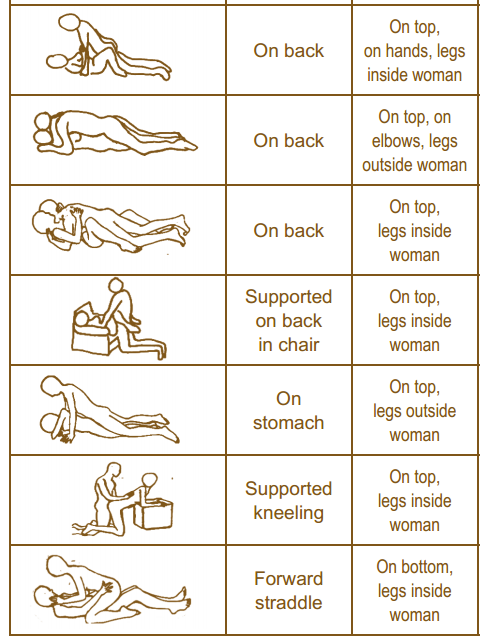

It is important to remember that just because a patient is not in our office for a directly related sexual problem, it is still important to at least open up the dialogue about sexual health. One study in 2013 had patients complete a questionnaire on their sexual function after undergoing a total hip or total knee replacement and 90% reported improved overall sexual functionRathod, et al.. We should try to make the conversation part of our routinely delivered information for a total joint replacement, for example when telling our THR patient, you can resume driving at 3-6 weeks (or when cleared by surgeon), you have Range of Motion precautions of avoiding internal rotation, hip flexion past 90 degrees, and hip adduction (crossing the legs) for the length specified by your surgeon (if it was a posterior approach THR), and you can resume sexual function at 3-6 weeks (or when cleared by the surgeon), or when you feel ready after that. It is important to give the patient some kind of guideline about when they can expect to resume sexual activity, however, always emphasize that it should be resumed when the patient is ready so they don’t feel pressured before they are ready. Also as pelvic rehab practitioners we can offer them guidance about what positions may be best for them when returning to sexual activity to put less strain on the prosthesis and hip as well as help them be comfortable. To continue with our example for THR (posterior approach) their precautions are likely to restrict hip flexion past 90 degrees, hip internal rotation, and adduction, so for a man or woman following THR lying on their back would be a safe position.

As physical therapists it is our job to provide guidance. Instead of telling people what not to do, helping them find a safe way to do things they want to do to maintain function should always be our goal. Sexual activity participation is definitely an important function for quality of life that is often overlooked and not discussed, so talk to your patient about it, they will likely appreciate it.

One useful tool to learn more about positioning for sexual activity is the Herman & Wallace product “Orthopedic Considerations for Sexual Activity.” It provides a great list of positions with pros and cons of each position, and is a helpful visual aid for your patients to help them return to sexual function safely with consideration of their respective injuries.

Baldursson, H., & Brattström, H. (1979). Sexual difficulties and total hip replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology, 8(4), 214-216.

Wright, J. G., Rudicel, S. A. L. L. Y., & Feinstein, A. R. (1994). Ask patients what they want. Evaluation of individual complaints before total hip replacement. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British Volume, 76(2), 229-234.

Rathod PA, Deshmuka AJ, Ranawat AS, Rodriguez JA. Sexual function improves significantly following total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective study. Program and abstracts of the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; March 19-23, 2013; Chicago, Illinois. Poster P023.

After pushing a double stroller for a 3 mile run to the park yesterday, I had a flare up of hip pain that made me doubt my ability to get my kids back home. While they were playing, a hanging ladder caught my eye and sent my manual therapy wheels spinning. I carefully slipped my leg over one of the rungs, angled my body just right, and leaned away to distract my hip. I noticed a toddler staring at me, so I politely told her, “I’m just mobilizing my hip joint, sweetie, but you can go ahead and climb now!” My relief was almost immediate, and I realized my patients need to know how to help themselves, too! We all know how to prescribe home exercises for patients regarding stretching and strengthening, but once a therapist is competent performing joint mobilizations, the need for this arthokinematic movement is often found to be essential prior to the osteokinematic movement of stretching. The hip joint in particular is affected by pathologies of the lumbar spine, the sacroiliac joint, and the pelvic floor. When the hip joint is not moving around the proper physiological axis, then the knee can be negatively impacted as well as the areas just mentioned.

Therapists need to discern whether a patient is appropriate for self-hip mobilization instruction, as a “motor moron” probably would not be a good candidate to whom you would explain how to perform mobilizations at home. When you realize a patient “gets it,” then you can suggest the techniques to that patient. Reiman and Matheson (2013) presented a paper regarding suggestions for self-mobilization of the hip joint. They demonstrate an inferior-posterior hip glide with a towel, weight, and a step with or without muscle reeducation in hip flexion; an inferior and lateral glide with hip flexion movement; a hip posterior glide with or without movement; a hip lateral glide with or without muscle reeducation; a hip anterior glide with or without muscle reeducation; and, a long axis distraction mobilization. The authors conclude the efficacy of their protocol and techniques are not completely backed up by evidence yet and recommend they be implemented as an adjunct to evidence based practice, not a primary treatment approach.

Therapists need to discern whether a patient is appropriate for self-hip mobilization instruction, as a “motor moron” probably would not be a good candidate to whom you would explain how to perform mobilizations at home. When you realize a patient “gets it,” then you can suggest the techniques to that patient. Reiman and Matheson (2013) presented a paper regarding suggestions for self-mobilization of the hip joint. They demonstrate an inferior-posterior hip glide with a towel, weight, and a step with or without muscle reeducation in hip flexion; an inferior and lateral glide with hip flexion movement; a hip posterior glide with or without movement; a hip lateral glide with or without muscle reeducation; a hip anterior glide with or without muscle reeducation; and, a long axis distraction mobilization. The authors conclude the efficacy of their protocol and techniques are not completely backed up by evidence yet and recommend they be implemented as an adjunct to evidence based practice, not a primary treatment approach.

Regarding the efficacy of hip mobilization in the clinic by a skilled clinician, a study by Makofsky et al, (2007) discusses the effect of inferior hip joint mobilization on hip abductor force. This study leaves little doubt that mobilizing the hip can facilitate contraction of the gluteus medius. A 17.35% increase in hip abduction torque was noted immediately after the inferior Grade IV hip mobilization; whereas, the control group without mobilization experienced a 3.68% decrease in hip abduction torque. We generally see patients much less often than our services are needed, so being able to teach patients how to mobilize on their own to supplement our work could be extremely effective in the long run.

I have the extreme fortune of being married to a manual therapist, so I do not always have to find crafty ways to mobilize my own joints, but my recent experience was encouraging to know it is more than possible to help myself. My hip pain had caused some patellofemoral symptoms because my gluteal muscles were inhibited. Performing a self-distraction close to my hip joint helped kick in the muscles required for greater stability of my knee. I cruised home with the kids without a hitch. We should all be ready to educate our patients to take potentially embarrassing measures to help themselves as well.

Reiman, M. P., & Matheson, J. W. (2013). RESTRICTED HIP MOBILITY: CLINICAL SUGGESTIONS FOR SELF‐MOBILIZATION AND MUSCLE RE‐EDUCATION. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 8(5), 729–740.

Makofsky, H., Panicker, S., Abbruzzese, J., Aridas, C., Camp, M., Drakes, J., … Sileo, R. (2007). Immediate Effect of Grade IV Inferior Hip Joint Mobilization on Hip Abductor Torque: A Pilot Study. The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 15(2), 103–110.

The following is contributed by faculty member Ginger Garner, who teaches the Hib Labrum Injury course. You can read more about that course on the Herman & Wallace course page.

Hip labral injury (HLI) is a relatively new diagnosis in the last 10 years of orthopaedic and rehabilitative care. However, just because HLI is a new diagnosis doesn’t mean the injury is new. In fact, HLI is posited to be responsible for the premature aging and osteoarthritis of the hip joint and pelvis that leads to hip replacements. HLI is also a major source of hip pain, with groin pain being the most common subjective complaint.However, groin pain is not the only complaint that is associated with HLI. Pelvic pain commonly goes hand-in-hand with hip pain.

What does this mean for patients? If you have hip or pelvic pain you should be evaluated by an HLI specialist, which can be a PT, surgeon, or osteopath who has received additional training on managing HLI. It is critical that you see someone who specializes in HLI. If HLI or other hip or pelvic injury is suspected, it is important that you follow up with a physical therapist who has had advanced training in HLI rehab for the best chance of recovery.

I find the premenstrual cycle pain (usually 1-5 days before the cycle begins) is a common phenomenon with many women with HLI (operative and non-operative), which is an area that needs more attention in research. Some women say it feels like they have retorn their labrum, and as a result, they get fearful – which affects not just their physical functioning but their psychoemotional and social well-being.

They limit activity which can exacerbate faulty neuromuscular patterning and deconditioning and result in increased pain from faulty structural support. Their realm of social activity and self-efficacy can suffer, which is also not good for long-term well-being.

Additionally, sleep can be interrupted with HLI and pelvic pain, which can dysregulate the HPA (hypothalamic pituitary adrenal) Axis and cause further problems with issues like pain centralization, cortisol dysregulation, and digestion. A recent study correlated vulvodynia and FAI (femoracetabular impingement), a type of hip impingement commonly found with HLI. The study found that those women who received early surgical intervention received the most relief from vulvodynia, while those who had a longer duration of pain did not experience the same level of improvement.

The take-home message is that early intervention for HLI is absolutely critical for the best long-term prognosis, and that pelvic pain, which can include anything from vulvodynia, dyspareunia, interstitial cystitis, non-relaxing pelvic floor/myalgia, pudendal neuralgia or entrapment, athletic pubalgia, and/or continence issues, although a common occurrence with HLI, is not normal and should be addressed by a trained pelvic rehab professional.

Want more? Read my post about Hip Labrum Tear Risk: Why Early Care is Critical, is absolutely necessary for the best long-term prognosis.