Sometimes as rehab providers, we find patients have deep posterior pain, or they have a “hitting something” sensation with intimacy. Maybe they have a deep pelvic ache or nerve sensation with sitting or passing bowels.

We know the deep structures all have the word “coccygeus” in them: iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and coccygeus. We also know there are ligaments that attach to this coccyx (sacrospinous ligament and sacrotuberous ligament), creating a web of support in the posterior pelvis, which has very little bony structure. When we are treating someone with deep vaginal or deep posterior pelvic pain, do we really have to “go there” and treat the coccyx internally?

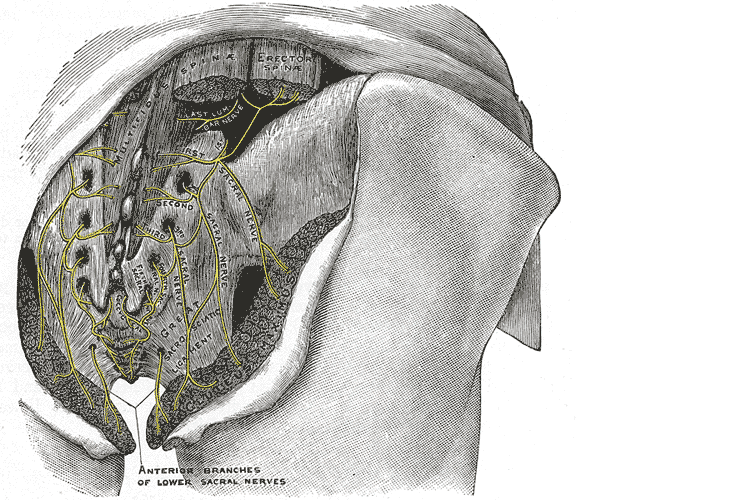

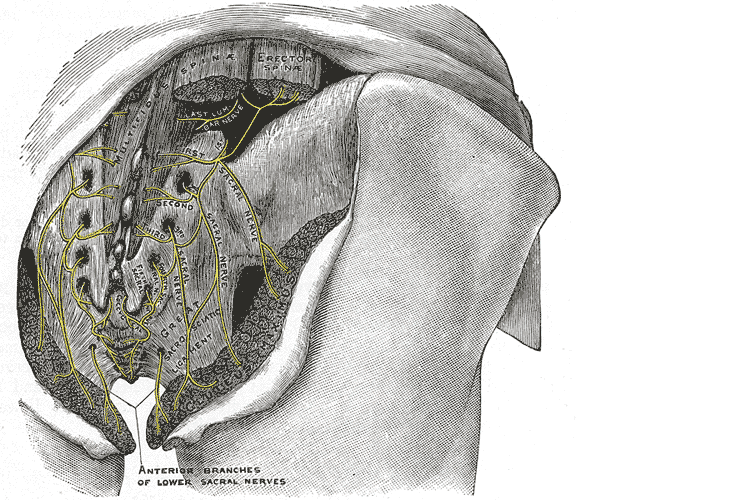

Did you know that actual spinal cord fibers enter the top of the sacral foramen, travel through this tunnel in the sacrum, and come out the bottom, where they fuse with the posterior coccygeal ligament on the dorsal surface of the coccyx? They can be a tremendous source of neural and pain dysfunction in the pelvis.

In addition, the gluteus maximus attaches at the coccyx, as well as attachments from a deep bowl of fascia, called the endopelvic fascia, that lines the pelvis. The endopelvic fascia is a tremendous source of support in the pelvis but is also often a pain generator. On top of this, the massive sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments also attach at the sacrococcygeal junction.

In Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment, scheduled for May 31 through June 1, we spend time addressing how to externally treat the deep structures that attach at the posterior pelvic floor and coccyx. We address ways to treat the incredibly dense sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments that attach to the coccyx from the outside. All of the nerves that supply the posterior hip, glutes, and pelvic floor squeeze between the piriformis and the sacrospinous ligament. This site where these nerves, including the pudendal, sciatic, inferior gluteal, nerve to obturator internus, and posterior femoral cutaneous, can also be a common site of dysfunction and compression. We will learn how to decompress all of this in class, as well as the surrounding soft tissues.

So, coming back to our question. With all this soft tissue and ligament work that can be external, can we forego internal rectal work? Actually….no. Both are important. The best way to treat a side-bent coccyx or an excessively flexed coccyx is internally. However, the real magic is addressing the alignment interiorly and then addressing all the softer tissues (ligaments, fascia, skin, muscle) that keep pulling the bone back into its old bad habits and misalignment.

AUTHOR BIO:

Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC

Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC (she/her) has been teaching with the institute since 2004. She has written the following courses: Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment /Treatment and Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment/Treatment. She has co-authored the PF Series Capstone course with Allison Ariail and Jenna Ross, and the Boundaries, Self Care, and Meditation Course (the burnout course) with Jenna Ross. In addition to teaching the classes she has authored, Nari also teaches all the other classes in the PF series: PF1, PF2A, PF2B, and Capstone. She was one of the question authors for the PRPC, and she has presented at many conferences, including CSM.

Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC (she/her) has been teaching with the institute since 2004. She has written the following courses: Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment /Treatment and Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment/Treatment. She has co-authored the PF Series Capstone course with Allison Ariail and Jenna Ross, and the Boundaries, Self Care, and Meditation Course (the burnout course) with Jenna Ross. In addition to teaching the classes she has authored, Nari also teaches all the other classes in the PF series: PF1, PF2A, PF2B, and Capstone. She was one of the question authors for the PRPC, and she has presented at many conferences, including CSM.

Nari’s passions include teaching students how to use their hands more receptively and precisely for advanced manual therapy skills while keeping it simple enough to feel

So often, we think of vulvodynia as a condition of the skin. And it is….kind of. Vulvodynia is a long-term pain (or burning, discomfort, or itching) that is present in the outer genitals, also known as the vulva. This condition is defined as a discomfort that has lasted longer than 3 months. The symptoms of vulvodynia can vary. In some patients, it is provoked (brought on by touch or stimulation), and in some cases, it is unprovoked (present without stimulation). Some patients have pain just in the outer vulva, while others also present with pelvic floor muscle tension or urethra, bladder, or vaginal canal irritation.

The definition of vulvodynia itself states there is no known reason. This means it is not because of a skin disruption, hormonal disorder, herpes or other skin conditions, or active infection, such as yeast. This means we really don’t know just why a person has symptoms once they have been medically ruled out.

When we look at the symptoms of neuralgia (an irritated or overly talkative nerve), we find symptoms listed such as pain, hypersensitivity, burning, tingling, itching, or trigger points. Certainly, there is a lot of overlap between neuralgia symptoms and vulvodynia symptoms.

When there is compression of a nerve, it can create neuralgia of the affected dermatome. In fact, in studies, we find neural proliferation of the peripheral nerve with vulvodynia in cell biopsy in women or in animal models (1, 2). Often, neural compression is part of the problem, and this is why we see treatment models proving effective at times with nerve blocks or nerve decompression (3, 4).

Of course, when treating such patients, we can and should still employ proven topical agents to make the treatments comfortable and effective, such as lidocaine solutions (5). Vulvodynia is best treated and managed as a team, with manual therapy and patient education from pelvic health providers being a very important limb of treatment.

By treating fascial tunnels that nerves run through, treating the fascia around the clitoris, and treating the deep fascia and tissues of the labia majora and mons, we can have an effect on the pudendal nerve branches, as well as the genitofemoral and ilioinguinal nerves supplying this region. In Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment scheduled for May 17-18, and Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment scheduled for May 31-June 1, both heavy manual therapy classes, we learn to decompress the neurovascular bundle from proximal to distal and to treat distal soft tissue structures that may be compressing nerves.

Resources:

1. Goetsch MF, Morgan TK, Korcheva VB, Li H, Peters D, Leclair CM. Histologic and receptor analysis of primary and secondary vestibulodynia and controls: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:614.e1–614.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.028.

2. Bornstein J. Vulvar disease. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. Vulvar pain and vulvodynia; pp. 343–367.

3. Vulvodynia treatments, National Vulvodynia Association (nva.org)

4. Possover M, Forman A. Pelvic Neuralgias by Neuro-Vascular Entrapment: Anatomical Findings in a Series of 97 Consecutive Patients Treated by Laparoscopic Nerve Decompression. Pain Physician. 2015 Nov;18(6):E1139-43. PMID: 26606029.

5. Loflin BJ, Westmoreland K, Williams NT. Vulvodynia: A Review of the Literature. J Pharm Technol. 2019 Feb;35(1):11-24. doi: 10.1177/8755122518793256. Epub 2018 Aug 20. PMID: 34861006; PMCID: PMC6313270.

AUTHOR BIO:

Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC

Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC (she/her) has been teaching with the institute since 2004. She has written the following courses: Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment /Treatment and Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment/Treatment. She has co-authored the PF Series Capstone course with Allison Ariail and Jenna Ross, and the Boundaries, Self Care, and Meditation Course (the burnout course) with Jenna Ross. In addition to teaching the classes she has authored, Nari also teaches all the other classes in the PF series: PF1, PF2A, PF2B, and Capstone. She was one of the question authors for the PRPC, and she has presented at many conferences, including CSM.

Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC (she/her) has been teaching with the institute since 2004. She has written the following courses: Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment /Treatment and Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment/Treatment. She has co-authored the PF Series Capstone course with Allison Ariail and Jenna Ross, and the Boundaries, Self Care, and Meditation Course (the burnout course) with Jenna Ross. In addition to teaching the classes she has authored, Nari also teaches all the other classes in the PF series: PF1, PF2A, PF2B, and Capstone. She was one of the question authors for the PRPC, and she has presented at many conferences, including CSM.

Nari’s passions include teaching students how to use their hands more receptively and precisely for advanced manual therapy skills while keeping it simple enough to feel successful. She also is an advocate for therapists learning how to feel well and thrive as they care for others, which is a skill that can be developed. “Basically, I love helping therapists learn to help themselves and others more while having a lot of fun doing it.” Nari lives in Portland Oregon, where she runs a local study/mentoring group and has a private practice, Portland Pelvic Therapy. Her interests include meditation, working out, nature, and being constantly humbled from raising her three amazing teenagers!

Pelvic pain can often involve adverse neural tension. The hip and pelvic nerves wrap around like spaghetti, making diagnosis and treatment difficult. Is the pain driver boney, capsular, muscle or neurovascular? Luckily, impingement and labral tears are fairly easy to diagnosis. Nerve entrapment can be a little bit tricky to diagnosis and treat. Part of being a good pelvic floor physical therapist is appropriately diagnosing and then partnering with patients to treat symptoms, pain, and movement dysfunction.

The authors of this study focused on hip, so this blog focuses on sciatic and pudendal nerve entrapment in the athletic population. Nerve entrapment occurs when the normal slide and glide is limited. That can be from any structure in the pelvis and hip region that cause strain or compression on the nerves in the area. Often patient’s descriptions of pain can be the first sign with complaints of ‘burning’, ‘sharp’, or changes in sensation. Evaluation for changes in reflexes and motor function are helpful. Other signs of nerve entrapment are tenderness to palpation and reproduction of pain with movements that elongate the nerve. Medical management to confirm diagnosis include nerve blocks, and diagnostic imaging, and nerve conduction velocity tests.

The authors of this study focused on hip, so this blog focuses on sciatic and pudendal nerve entrapment in the athletic population. Nerve entrapment occurs when the normal slide and glide is limited. That can be from any structure in the pelvis and hip region that cause strain or compression on the nerves in the area. Often patient’s descriptions of pain can be the first sign with complaints of ‘burning’, ‘sharp’, or changes in sensation. Evaluation for changes in reflexes and motor function are helpful. Other signs of nerve entrapment are tenderness to palpation and reproduction of pain with movements that elongate the nerve. Medical management to confirm diagnosis include nerve blocks, and diagnostic imaging, and nerve conduction velocity tests.

Specific locations of pain can help determine where the nerve is being squished. The sciatic nerve (L4-S3) can be entrapped as it passes between the piriformis and deep hip rotators. This often presents with a history of trauma to the gluteal area and limited sitting tolerance (>30 minutes). As the sciatic nerve moves down it can have ischiofemoral impingement, when the nerve gets compressed between lateral ischial tuberosity and greater trochanter at level of quadratus femoris muscle. This will often present as pain during mid- to terminal-stance during walking. Then, once the sciatic nerve clears the pelvis it can become entrapped by the proximal hamstring. There can be hamstring trauma in the history, and possible partial avulsion or thickening of the hamstring may entrap the sciatic nerve.

The pudendal nerve (S2-S4) can become entrapped in several areas and symptoms often include pain medial to the ischium and can include genital regions for all genders, perineum, and peri-rectal regions. The most common areas consist of the space between the posterior pelvic ligaments (sacrospinous and sacrotuberous) and the obturator internus muscle. History often includes bike riding, and a common complaint is pain with sitting, except a toilet seat.

Differential diagnosis for posterior nerves physical examination can include the following tests:

Sciatic Nerve

- Seated palpation: where the clinician palpates the subgluteal space (between sacrum and deep hip rotators), ischial tuberosity and hamstring attachment, and in the area medial to ischial.

- Seated piriformis stretch - involved lower extremity is adducted and internally rotated while palpating posterior hip region.

- Active piriformis - resisted lateral abduction and external rotation while palpating posterior hip region.

- Ischiofemoral impingement: the involved is placed in extension with adduction and external rotation

- Active knee flexion: this test is done seated with knee at 30° and 90° flexion. Clinician palpates ischial canal while providing knee flexion resistance for 5 seconds in both positions.

Pudendal Nerve

- Palpation around sciatic notch, region medial ischium

- Internal palpation for obturator internus tenderness

- Internal palpation of alcocks canal

Consertative treatment including physical therapy can be helpful. Manual therapy including nerve glides and soft tissue mobilization. Nerve mobilizations require anatomical nerve pathway knowledge. Mobilizing the nerves is thought to improve blood flow within and around the nerve, decrease adhesions, and also may affect central sensitivity. Soft tissue mobilization is geared towards positively affecting scar tissue and encouraging movement that may be restricting neural movement.

Therapeutic exercises for strengthening and stretching are also helpful, however use caution to avoid aggressive stretching as it may aggravate nerves. Exercises to promote load transfer through the pelvis and lower extremities can be helpful. The authors also suggest lower extremity passive PNF (proprioceptive neurofacilitation) diagonal movements. The authors also suggest aerobic conditioning, cognitive behavioral therapy, and for the chronic pelvic pain population, pelvic floor muscle training that does not provoke symptoms.

When conservative treatment including injections produces limited results, surgical treatments are often the next step. Often surgeries where the nerves are decompressed, neurolysis, or removed, neurectomy can be helpful.

To learn more nerve assessment and treatment techniques, join Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC in her course Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment in Tampa, FL this December 6-8, 2019!

Martin R, Martin HD1, Kivlan BR 2.Nerve Entrapment In The Hip Region: Current Concepts Review.Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Dec;12(7):1163-1173.

“My butt hurts.” This is such a common subjective complaint in my practice as a manual therapist, and many patients insist it must be a muscle problem or jump to the conclusion it must be “sciatica.” I often tell patients if they did not get shot or bit directly in the buttocks, the pain is most likely referred from nerves that originate in the spine. Although blunt trauma to the buttocks can certainly be the culprit for pain in the gluteal region, a basic understanding of the neural contribution is essential for providing appropriate treatment and a sensible explanation for patients.

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

Iwananga et al., (2018) presents a very recent article regarding the innervation of the piriformis muscle, which has been suspected to be the superior gluteal nerve, by dissecting each side from ten cadavers. Often the piriformis muscle can be compromised through total hip replacements with a posterior approach, hip injuries, or chronic pain disorders. This particular study verifies there is no singular nerve that innervates the piriformis muscle, and the most common innervation sources are the superior gluteal nerve (70% of the time) and the ventral rami of S1 (85% of the time) and S2 (70% of the time). The inferior gluteal nerve and the L5 ventral ramus were each found to be part of the innervation only 5% of the time.

Wang et al., (2018) focused on what causes gluteal pain with lumbar disc herniation, particularly at L4-5, L5-S1. They emphasize the important factor that dorsal nerve roots have sensory fibers and ventral roots contain motor neurons, and spinal nerves are mixed nerves, since they have ventral and dorsal roots. They discuss other contributing nerves, but continuing our focus on the superior gluteal nerve, it stems from L4-S1 ventral rami and not only allows movement of gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and gluteus maximus, it also provides sensation to the area. This nerve can certainly produce pain in the gluteal region when irritated. In lumbar disc herniation of L4-5 or L5-S1, the ventral rami of L5 or S1 can be comprised or irritated at the level of the nerve root and provoke gluteal pain because they mediate sensation in that area.

Once the superior gluteal nerve (or any sacral nerve) is implicated as the root of pain, should we just shrug our shoulders and send them to pain management? I strongly suggest we learn how to address the issue in therapy using our hands with manual techniques and appropriate exercises. The Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment course should be a priority on your bucket list of continuing education to help alleviate any further pain in the butt.

Lung K, Lui F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Superior Gluteal Nerve. [Updated 2018 Dec 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535408/

Iwanaga J, Eid S, Simonds E, Schumacher M, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. (2018). The Majority of Piriformis Muscles are Innervated by the Superior Gluteal Nerve. Clinical Anatomy. doi: 10.1002/ca.23311. [Epub ahead of print]

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Yan, Y., Zhang, L., Guo, C., Peng, Z., & Kong, Q. (2018). Possible pathogenic mechanism of gluteal pain in lumbar disc hernia. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 19(1), 214. doi:10.1186/s12891-018-2147-y

Faculty member Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC recently created a two-course series on the manual assessment and treatment of nerves. The two courses, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment and Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment, are a comprehensive look at the nervous system and the various nerve dysfunctions that can impact pelvic health. The Pelvic Rehab Report caught up with Nari to discuss these new courses and how they will benefit pelvic rehab practitioners.

What is "new" in our understanding of nerves? Are there any recent exciting studies that will be incorporated into this course?

The course is loaded with a potpourri of research regarding nerves and histological and morphological studies. There are some fascinating correlations we see with nerve restrictions, wherever they are in the body. Frequently the nerves are compressed in fascial tunnels or areas of muscular overlap, then the nerve, wherever the location, frequently has local vascular axonal change, which increases the diameter of the nerve and prohibits gliding without pain. This causes local guarding and protective mechanisms. Changing pressure on the nerve can change that axonal swelling and allow gliding without pain.

New pain theory also supports that much of pain perception is the body perceiving danger or injury to a nerve. By clearing up the path of the nerve and mobilizing it, we can decrease the body's perception of nerve entrapment and thus create change in pain levels.

What do you hope practitioners will get out of this series that they can't find anywhere else?

I hope they will leave the course able to treat the nerves of the region, which is essentially the transmission pathway for most pelvic pain. I don't know of other courses that have this emphasis.

You've recently split your nerve course in two. Why the split?

I didn't want this class to be a bunch of nerve theory without the manual intervention to make change. After running the labs in local study groups, we found it took more time for people's hands to learn the language, art, and techniques of nerve work. To truly do the work justice and for participants to have a firm grasp of the manual techniques without being rushed, we found it takes time, and I wanted to honor that, as well as treating enough of the related factors and anatomy to make real and lasting change for patients.

How did you decide to divide up content?

Basically, we divided them up by anatomical origin:

The lumbar course covers the nerves of the lumbar plexus, the abdominal wall when treating diastasis, and treatment of the inguinal canal (obturator nerve, femoral nerve, iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral nerves). Also, the lumbar nerves have more effect in the anterior hip, anterior pelvis, and abdominal wall.

The sacral nerve course covers all the nerves of the sacral plexus (pudendal, sciatic, gluteal/cluneal, posterior femoral cutaneous, sciatic, and coccygeal nerves), as well as subtle issues in the sacral base and subtle coccyx derangement work as well as the relationship with the uterus and sacrum, to take pressure off the sacral plexus. The sacral nerves have more effect in the posterior and inferior pelvis and into the posterior leg and gluteals.

What are the main stories that either course tells?

Both courses tell the story of getting closer to the root of the pain to make more change in less time. Muscles generally just respond to the message the nerve is sending. Yet, by treating the nerve compression directly, we are getting much closer to the root of the issue and have more lasting results by changing the source of abnormal muscle tone. Rather than an intellectual exercise of discourse on nerves, we devote ourselves to the art of manual therapy to change the restrictions on the pathway of the nerve and in the nerve itself.

If someone went to the old nerve course, what's the next best step for them?

The first course was initially all the lumbar nerves with a dip into the pudendal nerve. They would want to take the sacral nerve course, as those nerves were not covered in the first round.

Anything else you would like to share about these courses?

Sure. Essentially, we will take each nerve and do the following:

- Thoroughly learn the path of the nerve

- Fascially clear the path of the nerve

- Manually lengthen supportive structures and tunnels that surround the nerve.

- Directly mobilize the nerve

- Glide the nerve

- Learn manual local regional integration techniques for the nerve after treatment

- Receive handouts for and practice home program for strengthening and increasing mobility in the path of the nerve

Join Nari at one of the following events to learn valuable evaluation and treatment techniques for sacral and lumbar nerves

Upcoming sacral nerve courses:

Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment - Winfield, IL

Oct 11, 2019 - Oct 13, 2019

Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment - Tampa, FL

Dec 6, 2019 - Dec 8, 2019

Upcoming lumbar nerve courses:

Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment - Phoenix, AZ

Jan 11, 2019 - Jan 13, 2019

Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment - San Diego, CA

May 3, 2019 - May 5, 2019