Many therapists start their career feeling a bit intimidated to work with women who are pregnant. A common and understandable concern is that something the therapist will do during examination or treatment may harm the patient. While there are certainly things to avoid when working with a patient who is pregnant there are also many therapeutic strategies that can help a woman thrive during her pregnancy and beyond. When women have pre-existing issues such as a disease or physical challenge, or when she develops an illness during pregnancy, the therapist needs to rely upon more knowledge- this knowledge is something she rarely learns in school, but more likely in continuing education environments. A recent article asked the question “are women getting sicker, and are there more high-risk pregnancies now than ever before?”

Researchers studied trends in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States in order to answer this question, and the answer is a definitive “yes”. Several studies describe increases in the rates of maternal morbidity, with issues such as cardiac and pulmonary complications, and the severe blood pressure fluctuations associated with eclampsia. Gestational diabetes, and postpartum rates for hemorrhage, perineal lacerations, and maternal infections have also risen. Part of the reason for more women carrying pregnancies more successfully or longer when they are ill may be contributed to newer treatments for conditions such as diabetes, yet this does not explain entirely the increase in maternal morbidity. Increased cesarean births, longer labors with epidural anesthesia, pre-pregnancy obesity, rates of multifetal pregnancies, and the rising age of mothers are other factors to be considered.

Researchers studied trends in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States in order to answer this question, and the answer is a definitive “yes”. Several studies describe increases in the rates of maternal morbidity, with issues such as cardiac and pulmonary complications, and the severe blood pressure fluctuations associated with eclampsia. Gestational diabetes, and postpartum rates for hemorrhage, perineal lacerations, and maternal infections have also risen. Part of the reason for more women carrying pregnancies more successfully or longer when they are ill may be contributed to newer treatments for conditions such as diabetes, yet this does not explain entirely the increase in maternal morbidity. Increased cesarean births, longer labors with epidural anesthesia, pre-pregnancy obesity, rates of multifetal pregnancies, and the rising age of mothers are other factors to be considered.

The more we know as health care providers about how maternal morbidity affects our rehabilitation efforts, the more we can contribute to a woman’s pregnancy and postpartum health. If you would like to learn more about caring for women during pregnancy and during the postpartum period, Herman & Wallace offers the Pregnancy and Postpartum Series. The following courses are available this year:

Care of the Pregnant Patient - Somerset, NJ

Apr 30, 2016 - May 1, 2016

Care of the Pregnant Patient - Akron, OH

Sep 10, 2016 - Sep 11, 2016

Peripartum Special Topics - Seattle, WA

Nov 12, 2016 - Nov 13, 2016

Tillett, J. (2015). Increasing Morbidity in the Pregnant Population in the United States. The Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing, 29(3), 191-193.

Food, at its basic level, provides us with nutrition and sustenance to perform our daily activities. Populations in tune with nature’s cycles of food tend to eat what is available locally based on climate and growth seasons. When societies move beyond simply eating food for energy, but also for flavor, pleasure, and even status, the face of nutrition changes. Whereas some diseases come from a lack of nutrition, many diseases we are faced with in the United States also come from an overabundance of food, with too many calories or too much sugar making up common causes of lack of health. The knowledge within the field of disordered eating is vast, and patients struggling with disordered eating may be fortunate enough to work with a specialist to help recover healthier habits. Even without a diagnosis of disordered eating, many us can identify with unhealthy eating habits, often guided by stress, fatigue, or emotions.

Prior research has studied how we access willpower under different conditions of cognitive stress. In part of this research, participants were given a number to recall (either 2 digits or 7 digits) and then while walking to another location were offered a snack of either fruit salad or chocolate cake. The authors found that the participants who had to recall a 7 digit number more often chose the chocolate cake, leading the researchers to theorize about the role of higher-level processing and making choices. (Shiv et al., 1999) While we may be aware of a tendency to overeat (or make poorer food choices) during times of stress, fatigue, or emotional distress, changing the habits can be very challenging.

Prior research has studied how we access willpower under different conditions of cognitive stress. In part of this research, participants were given a number to recall (either 2 digits or 7 digits) and then while walking to another location were offered a snack of either fruit salad or chocolate cake. The authors found that the participants who had to recall a 7 digit number more often chose the chocolate cake, leading the researchers to theorize about the role of higher-level processing and making choices. (Shiv et al., 1999) While we may be aware of a tendency to overeat (or make poorer food choices) during times of stress, fatigue, or emotional distress, changing the habits can be very challenging.

Resources that discuss improving our eating choices in the face of “emotional eating” offers many alternatives, or ways to soothe ourselves without eating. In her books about this topic, clinical psychologist Susan Albers offers advice that may be helpful for our own habit building and for offering basic advice for our patients who struggle with the issue. (While offering advice to patients about healthy eating and habits is within our scope of practice, if a patient has need for a referral to a counselor, psychologist, or nutritionist, we can coordinate such a referral with the patient’s primary care provider.) In her book titled “50 More Ways to Soothe Yourself Without Food: Mindfulness Strategies to Cope with Stress and End Emotional Eating”, Dr. Albers offers many strategies for altering our habits. Some of these ideas include using acupressure points, breathing, rituals, self-massage, yoga, writing, dancing, art, tea, or sex to defer ourselves from poor eating habits. While eating can be enjoyable and pleasurable, when our patients are struggling with over-eating or eating foods that don’t support nutritional or healing goals, having a discussion about these issues may be useful.

If you are interested in learning more about nutrition, consider joining your pelvic rehab colleagues at one of the two Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist courses this year! Your first chance to attend will be in Kansas City on March 5-6, and later on in Lodi, CA June 25-26.

Albers, S. (2015). 50 More Ways to Soothe Yourself Without Food: Mindfulness Strategies to Cope with Stress and End Emotional Eating. New Harbinger Publications.

Shiv, B., & Fedorikhin, A. (1999). Heart and mind in conflict: The interplay of affect and cognition in consumer decision making. Journal of consumer Research, 26(3), 278-292.

If you celebrated the Thanksgiving holiday by enjoying food with family or friends, you may be lamenting the sheer amount of food you ate, or the calories that you took in. Did you know that chewing your food well can not only affect how much you eat, but also how much nutrition you derive from food? In a meta-analysis by Miquel-Kergoat et al. on the affects of chewing on several variables, researchers found that chewing affects hunger, caloric intake, and even has an impact on gut hormones. Ten papers that covered thirteen trials were included in the meta-analysis. From these trials, the following data are reported:

- 10 of 16 studies found that prolonged chewing reduced a person’s food intake

- chewing decreases self-reported hunger

- chewing decreases amount of food intake

- increasing the number of chews per bite increases gut hormone release

- chewing promotes feeling full

Research about eating behavior theories are highlighted in this paper, and include a discussion of the variety of factors, both internal and external, that control eating. Chewing is described as providing “…motor feedback to the brain related to mechanical effort…” that may influence how full a person feels when eating foods that are chewed. On the contrary, foods and beverages that do not require much chewing may be associated with overconsumption due to the lack of chewing required. (This makes sense when considering sugar-laden, high-calorie beverages.) Additionally, chewing food mixes important digestive enzymes and breaks down the food properly in the mouth, making the process of digestion further along the digestive tract more efficient. Another study by Cassady et al. which assessed differences in hunger when chewing almonds 25 versus 40 times reported that increased chewing led to decreased hunger and increased satiety when compared to chewing only 25 times.

The theory presented, yet not concluded, in this paper is that chewing may affect gut hormones and thereby decrease self-reported hunger and decrease food intake. For various reasons, including deriving more nutrition from our food, avoiding overconsumption, or making the process of digestion more efficient, focusing more on the act of chewing our food can have beneficial affects. To learn more about health and nutrition, attend the Institute’s course Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist (link: https://hermanwallace.com/continuing-education-courses/nutrition-perspectives-for-the-pelvic-rehab-therapist). This continuing education course was written and instructed by Meghan Pribyl, who is not only a physical therapist who practices in pelvic rehabilitation and orthopedics, but who also has a degree in nutrition. Her training and qualifications allow her to share important information that integrates the fields of rehabilitation and nutrition. Your next opportunity to take this course is in March in Kansas City.

Cassady, B. A., Hollis, J. H., Fulford, A. D., Considine, R. V., & Mattes, R. D. (2009). Mastication of almonds: effects of lipid bioaccessibility, appetite, and hormone response. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 89(3), 794-800. Miquel-Kergoat, S., Azais-Braesco, V., Burton-Freeman, B., & Hetherington, M. M. (2015). Effects of chewing on appetite, food intake and gut hormones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiology & behavior, 151, 88-96.

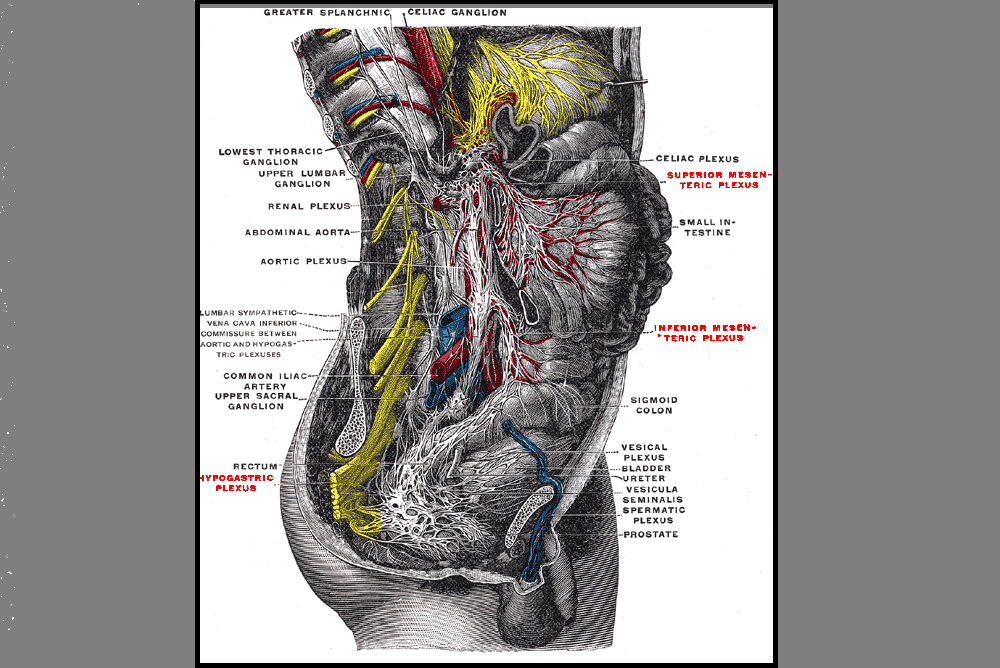

Inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (CD), according to Lan et al., are characterized by chronic inflammation in intestinal mucosa. There is little information available based on human studies that links nutritional support with inflammatory bowel disease. The authors of this article analyzed the available information about supplements that appear beneficial in healing the gut mucosa.

The intestinal epithelium acts as a selective barrier, and inflammatory bowel disease can disrupt this important barrier, affecting absorption, mucus production, and enteroendocrine secretion. Intestinal wound healing, according to the linked article, is “dependent on the precise balance of several processes including migration, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of the epithelial cells.” Although there are few human clinical studies (more are animal and cell model studies) there is evidence that both macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies may exist in patients who have inflammatory bowel disease. Patients may have malnutrition of proteins, of minerals and vitamins. Following are some points from the article:

The intestinal epithelium acts as a selective barrier, and inflammatory bowel disease can disrupt this important barrier, affecting absorption, mucus production, and enteroendocrine secretion. Intestinal wound healing, according to the linked article, is “dependent on the precise balance of several processes including migration, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of the epithelial cells.” Although there are few human clinical studies (more are animal and cell model studies) there is evidence that both macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies may exist in patients who have inflammatory bowel disease. Patients may have malnutrition of proteins, of minerals and vitamins. Following are some points from the article:

- Arginine, glutamine, and glutamate are noted as amino acids that contribute to mucosal healing in animal studies, as well as threonine, methionine, proline, serine, and cysteine.

- Short-chain fatty acids, which are the result of metabolized dietary fiber (grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables), and resistant starch (beans, potatoes, brown rice) are a major source of energy for epithelial cells in the colon

- Vitamin A deficiency is common in patients with newly diagnosed IBD

- Vitamin D may decrease intestinal fibrosis, and reduce risk of Crohn’s relapse

- Vitamin C and Zinc may both help heal epithelial wounds in the colon

- During the remission phase, some foods may be poorly tolerated, such as dairy

- During an active flare of IBD, a patient may require enteral nutrition

The authors conclude that the exact mechanisms by which the various dietary compounds contribute to bowel healing is still unknown. Furthermore, the ability to make clear dietary recommendations is limited by the lack of clinical studies. At a minimum, this information can alert the pelvic rehab provider to discuss the potential benefits of nutrition on bowel health with patients. Many of us are quite comfortable giving advice about drinking appropriate amounts and types of fluid, or eating more whole and less processed foods. We can take our nutritional education a step further by encouraging a patient to discuss healing supplements with a provider and/or nutritionist to best support the healing bowel. If you are interested in learning more about nutrition and pelvic health, you might love our newer course Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist Kansas City in March of next year with instructor Megan Pribyl.

Lan, A., Blachier, F., Benamouzig, R., Beaumont, M., Barrat, C., Coelho, D., & Tomé, D. (2015). "Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: is there a place for nutritional supplementation?" Inflammatory bowel diseases, 21(1), 198-207.

As pelvic rehab practitioners, it is common for our patients to ask us dietary questions pertaining to their unique pelvic floor symptoms. We often counsel on fluid consumption, bladder irritants, and fiber intake. At times, we even give our patients a bladder or bowel diary to better monitor nutritional status and habits. However, how often do we ask about vitamin D status? It is common knowledge that vitamin D deficiency contributes to osteoporosis, fractures, and muscle pain and weakness, but what is the role of vitamin D in overall health of the female pelvic floor. Is vitamin D supplementation something we as health care providers need to at least discuss? An article published in the International Urogynecology Journal (Parker-Autry) explores this topic. This interesting paper reviews current knowledge regarding vitamin D nutritional status, the importance of vitamin D in muscle function, and how vitamin D deficiency may play a role in the function of the female pelvic floor.

How may vitamin D play a role in the function of the pelvic floor?

Vitamin D affects skeletal muscle strength and function, and insufficiency is associated with notable muscle weakness. Vitamin D has been shown to increase skeletal muscle efficiency at adequate levels. The levator ani muscles and coccygeus pelvic floor muscles are skeletal muscle that are crucial supporting structures to the pelvic floor. Pelvic floor musculature weakness can contribute to pelvic floor disorders such as urinary or fecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Pelvic floor muscle training for strengthening, endurance, and coordination, are first line treatment for both stress and urge urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and overactive bladder syndrome. The pelvic floor muscles are thought to be affected by vitamin D nutrition status. Additionally, as women age, they are more prone to vitamin D deficiency and pelvic floor disorders.

Vitamin D affects skeletal muscle strength and function, and insufficiency is associated with notable muscle weakness. Vitamin D has been shown to increase skeletal muscle efficiency at adequate levels. The levator ani muscles and coccygeus pelvic floor muscles are skeletal muscle that are crucial supporting structures to the pelvic floor. Pelvic floor musculature weakness can contribute to pelvic floor disorders such as urinary or fecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Pelvic floor muscle training for strengthening, endurance, and coordination, are first line treatment for both stress and urge urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and overactive bladder syndrome. The pelvic floor muscles are thought to be affected by vitamin D nutrition status. Additionally, as women age, they are more prone to vitamin D deficiency and pelvic floor disorders.

This article reviews several studies, including small case and observational, that show an association between insufficient vitamin D and pelvic floor disorder symptoms and severity of symptoms. The recommendation from this review is that more studies of high quality evidence are needed to fully understand and demonstrate this relationship between vitamin D deficiency and pelvic floor disorders. However, the authors feel that vitamin D supplementation may be a helpful adjunct to treatment by helping to optimize our physiological response to pelvic floor muscle training and improving the overall quality of life for women suffering from pelvic floor disorders.

How much vitamin D?

The Institute of Medicine has only made recommendations for dietary allowance for vitamin D and calcium for bone health. There is no consensus for adequate vitamin D levels for a condition specific goal (other than bone health), and the levels of vitamin D varied throughout the reviewed studies. It has been shown that very high levels of vitamin D are tolerated well, so supplementation of vitamin D seems to be very safe in low and very high doses.

Food for thought?

As pelvic rehabilitation providers, it is our job to assess the whole person, however, we are not dieticians. As physical therapists we are musculoskeletal specialists and vitamin D affects muscle function. What our patients put in their bodies (wholesome nutritious food vs nutrient lacking artificial food) affects the quality of the cells they produce and tissues that are made, which can influence their healing. When reviewing health history, maybe consider discussing vitamin D status and possible supplementation with the patient, or with the patients’ primary care provider or naturopathic doctor. This team approach may provide more comprehensive health care, hopefully yielding more successful outcomes.

Parker-Autry, C. Y., Burgio, K. L., & Richter, H. E. (2012). Vitamin D status: a review with implications for the pelvic floor. International urogynecology journal, 23(11), 1517-1526.

Megan Pribyl, MSPT is the author and instructor for Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist. Megan is passionate about nutritional science and manual therapy. Megan holds a dual-degree in Nutrition and Exercise Sciences (B.S. Foods & Nutrition, B.S. Kinesiology) from Kansas State University, and has actively sought to fill in missing links between orthopedics and nutrition.

APTA Landmark Motion Passes

RC 12-15: The Role of the Physical Therapist in Diet and Nutrition

Is nutrition within our scope of practice? As the instructor for “Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist” offered through Herman & Wallace, I hear this question frequently! To me, the answer has always been a clear “yes*!”; now the APTA is endorsing this view. It’s an exciting time to be a rehab professional, especially for those looking to broaden clinical perspectives and scope of services to include basic nutrition and lifestyle information.

Is nutrition within our scope of practice? As the instructor for “Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist” offered through Herman & Wallace, I hear this question frequently! To me, the answer has always been a clear “yes*!”; now the APTA is endorsing this view. It’s an exciting time to be a rehab professional, especially for those looking to broaden clinical perspectives and scope of services to include basic nutrition and lifestyle information.

At the APTA House of Delegates in early June 2015, a landmark motion passed - RC 12-15: The Role of the Physical Therapist in Diet and Nutrition. As our profession advances towards a more integrative model, this motion symbolizes an acknowledgement of the rehab professional’s broader role as a health care provider. We, as physical therapists, are uniquely positioned to offer patients more comprehensive lifestyle-related education including discussion of nutrition. Both the World Health Organization (WHO, 2008) and the Physical Therapy Summit on Global Health (Dean, et.al, 2014) have called upon all health care providers to stand in unity to help the public with epidemics of lifestyle-related diseases; the APTA has given it’s nod of approval as well.

The motion states: “as diet and nutrition are key components of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of many conditions managed by physical therapists, it is the role of the physical therapist to evaluate for and provide information on diet and nutritional issues to patient, clients, and the community within the scope of physical therapist practice. This includes appropriate referrals to nutrition and dietary medical professionals when the required advice and education lie outside the education level of the physical therapist*.” Further, “this motion clearly incorporates the intent of the new Vision Statement for the Physical Therapy Profession by transforming society and improving the human experience.” (APTA, 2015)

This powerful development provides us with both challenge and opportunity. How can we, as pelvic rehab professionals, be armed with the most cutting edge nutritional information available? What nutrition information lies within our scope of practice? How can we apply this information to our pelvic rehab patient population? For the answer to these pressing questions and much more, plan now to attend Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist” March 5 & 6, 2016 in Kansas City, MO. It is my passion to share this information and I welcome you to join me for this timely CEU opportunity. It is designed to help you obtain the skills needed to confidently identify nutritional correlates in pelvic rehabilitation.

References:

ATPA (2015) http://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/2015PacketI.pdf

Dean, E., de Andrade, A. D., O'Donoghue, G., Skinner, M., Umereh, G., Beenen, P., . . . Wong, W. P. (2014). The Second Physical Therapy Summit on Global Health: developing an action plan to promote health in daily practice and reduce the burden of non-communicable diseases. Physiother Theory Pract, 30(4), 261-275. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24252072)

World Health Organization. (2008). 2008-2013 Action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of non communicable diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/noncommunicable-diseases/en/)

photo credit: Walmart’s locally grown produce via photopin (license)

This post was written by Megan Pribyl MSPT, who teaches the course Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist. You can catch Megan teaching this course in June in Seattle.

Convalescence and mitohormesis…really big words that in a scientific way suggest “BALANCE”. In our modern world, there are many factors that influence the pervasive trend of being “on” or in perpetual “go mode”. We see the effects of this in clinical practice every day. The sympathetic system is in overdrive and the parasympathetic system is in a state of neglect and disrepair. And so we reflect on that word “balance” through the concepts of convalescence and mitohormesis.

Convalescence and mitohormesis…really big words that in a scientific way suggest “BALANCE”. In our modern world, there are many factors that influence the pervasive trend of being “on” or in perpetual “go mode”. We see the effects of this in clinical practice every day. The sympathetic system is in overdrive and the parasympathetic system is in a state of neglect and disrepair. And so we reflect on that word “balance” through the concepts of convalescence and mitohormesis.

“In the past, it was taken for granted that any illness would require a decent period of recovery after it had passed, a period of recuperation, of convalescence, without which recurrence was possible or likely.

Convalescence fell out of favor as powerful modern drugs emerged. It appeared that [antibiotics] and the steroid anti-inflammatories produced so dramatic a resolution of the old killer diseases… that all the time spent convalescing was no longer necessary.” (Bone, 2013)

How many of us take the time to convalesce after even a minor cold or flu? “Convalescence needs time, one of the hardest commodities now to find.” (Bone, 2013) We live in a culture where getting well FAST typically takes priority over getting well WELL.

On the flip-side of convalescence lies mitohormesis, or stress-response hormesis. Simply put, hormesis describes the beneficial effects of a treatment (or stressor) that at a higher intensity is harmful. Without mitohormesis, the driving, adaptive forces of life might lie dormant or find dysfuction. In a recent article (Ristow, 2014) mitohormesis is discussed: “Increasing evidence indicates that reactive oxygen species (ROS) do not only cause oxidative stress, but rather may function as signaling molecules that promote health by preventing or delaying a number of chronic diseases, and ultimately extend lifespan. While high levels of ROS are generally accepted to cause cellular damage and to promote aging, low levels of these may rather improve systemic defense mechanisms by inducing an adaptive response.”

Relevant to nutritional trends, Tapia (2006) suggests this perspective: “it may be necessary…to engender a more sanguine perspective on organelle level physiology, as… such entities have an evolutionarily orchestrated capacity to self-regulate that may be pathologically disturbed by overzealous use of antioxidants, particularly in the healthy.” Think of mitohormesis as the cellular-level forces that spur change. Motivation….drive….exhilaration. These life-sprurring stressors include physical activity and glucose restriction among other interventions.

The natural world is full of contrasts; day and night, winter and summer, land and sea, sun and rain. These contrasts are not only essential in creating rhythm to our existence, but necessary as driving forces of life. But what happens when there is not a balance of activity and rest? What happens when our energy systems go haywire? What nutritional factors play a role in whether a client of yours will have a healing and helpful course of therapy or may struggle with the healing process? How might we frame our understanding of the importance of balance through the lens of nourishment?

March is “National Nutrition Month”! It’s a perfect time to register for our brand new continuing education course Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist to learn more about how nutrition impacts our clinical practice. To register for the course taking place in June in Seattle, click here.

References

Bone, K. Mills, S. (2013) Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy; Modern Herbal Medicine. Second Edition. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

Gems, D., & Partridge, L. (2008). Stress-response hormesis and aging: "that which does not kill us makes us stronger". Cell Metab, 7(3), 200-203. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.001

Ristow, M., & Schmeisser, K. (2014). Mitohormesis: Promoting Health and Lifespan by Increased Levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Dose Response, 12(2), 288-341. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.13-035.Ristow

Tapia, P. C. (2006). Sublethal mitochondrial stress with an attendant stoichiometric augmentation of reactive oxygen species may precipitate many of the beneficial alterations in cellular physiology produced by caloric restriction, intermittent fasting, exercise and dietary phytonutrients: "Mitohormesis" for health and vitality. Med Hypotheses, 66(4), 832-843. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.09.009