For over 25 years my practice has had a focus on children suffering from bloating, gas, abdominal pain, fecal incontinence and constipation. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGID) are disorders of the brain -gut interaction causing motility disturbance, visceral hypersensitivity, altered immune function, gut microbiota and CNS processing. (Hyams et al 2016). Did you know that children who experience chronic constipation that do not get treated have a 50% chance of having issues for life?

The entire GI system is as amazing as it is and complicated. Its connection to the nervous system is fascinating, making it a very sensitive system. In her book GUT, Giulia Enders talks about Ninety percent of the serotonin we need comes from our gut! The psychological ramifications of ignoring the problem are too great (Chase et el 2018). Last year an 18-year-old patient of mine had to decline a scholarship to an Ivy League University because she needed to live at home due to her bowel management problem.

The entire GI system is as amazing as it is and complicated. Its connection to the nervous system is fascinating, making it a very sensitive system. In her book GUT, Giulia Enders talks about Ninety percent of the serotonin we need comes from our gut! The psychological ramifications of ignoring the problem are too great (Chase et el 2018). Last year an 18-year-old patient of mine had to decline a scholarship to an Ivy League University because she needed to live at home due to her bowel management problem.

Unfortunately, FGID conditions can lead to suicide and death. Over 15 years ago my children’s pediatrician told me about an 11-year-old boy who hung himself because he had encopresis. In 2016 a 16-year-old girl suffered a cardiac arrest and died because of constipation.

The problems with children are different than for adults and need to be addressed with a unique approach.

How do physical therapists treat pediatric FGID?

- Have a solid foundation in the gastrointestinal system

- Coordinate muscle functions from top to bottom!

- Identify common childhood patterns

- Learn treatment techniques and strategies to address the issues specifically

Study and understand gastrointestinal anatomy, physiology, function and examination techniques. The entire GI system is as amazing as it is complicated. Its connection to the nervous system is fascinating, making it a very sensitive system. Ninety percent of the serotonin we need comes from our gut! The psychological ramifications of ignoring the problem are too great.

What do the Pelvic Floor Muscles (PFM) have to do with it?

Encopresis leads to a weak internal/external anal sphincter and pelvic floor muscles and constipation leads to pelvic floor muscles that can’t relax. Confused? When the Rectal Anal Inhibitory Reflex or RAIR fails from bypass diarrhea the sphincter muscles relax, and feces leaks out. This constant leakage leads to weak sphincter and pelvic floor muscles. When it happens on a regular basis most children don’t feel it, however their peers smell it and life changes.

My course, Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, teaches how to coordinate the muscle function based on the tasks required.

How did this start?

One painful bowel movement can lead to withholding for the next due to fear of the pain happening again. The muscles of the pelvic floor then tighten to hold the poop in. This actually does not make the muscle strong but instead makes it confused. The muscle then is controlled by the consistency of poop being too hard and painful to let out or too loose and not able to hold in.

Managing functional GI disorders is a process. It takes the bowel a long time to re-train and it requires patience and skill to know how to do it. Many therapists and patients themselves get frustrated and compliance fails. This is mostly due to lack of knowing how to titrate medications and give the bowel what it needs (other than proper nutrition that is!) It's like retraining a person to walk after a stroke, the brain needs to relearn normal bowel sensations.

Most families don’t realize how severe constipation can be. It is an insidious problem that gets ignored until it is too late.

Typically, what I hear from parents is their child was diagnosed with constipation and was advised to take a daily laxative. So, which one is the best one? How do they all work? Once leakage occurs again the laxative is discontinued as we think the bowel must be empty and this medication is causing the leaks which is counterproductive. Now the frustrating cycle of backing up or being constipated begins again. The constipation returns, the laxative is restarted, the loose stool leaks out and the laxative is stopped and that is the REVOLVING DOOR or what I refer to as children riding the “Constipation Carousel”. The bowel is an amazingly beautiful, smart but also sensitive organ that does not like this back and forth and therefore will not learn how to be normal. In the meantime, they experience distended abdomens and dysmorphia ending up in eating disorder clinics. I had an 11-year-old girl taking Amitriptyline for abdominal pain all because of a pressure problem in the gut not knowing how to work the pelvic floor with the diaphragm and her core.

No two children are the same and no two colons are the same. Laxatives need to be titrated to the specific needs of your child’s colon and motility of their colon not their age or body weight.

The success in getting children to have regular bowel movements of normal consistency without any fecal leaks is based not only teaching how to titrate laxatives but also how to sense urge, become aware of the pelvic floor muscles and learn how NOT to strain to defecate, retrain the core and diaphragm with the ribcage and integrate developmental strategies for function. Teaching Interoception- what my body feels like when I have an urge- is an important part of this course. This is especially important for those children born with anorectal malformations or congenital problems such as imperforate anus or Hirschsprung’s Disease.

In this class we use visceral techniques, manual therapy techniques, sensory techniques and neuromuscular reeducation and coordination to retrain the entire system.

Come and explore the amazing gut with me and learn how to improve the health and well-being of your patients, in Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders!

1. Hyams, JS, et al. Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Child/Adolescent. Gastroenterology volume 150, 2016;1456-1468.

2. Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1262-1279

3. Robin SG, Keller C, Zwiener R, et al. Prevalence of Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Utilizing the Rome IV Criteria. J Pediatr 2018; 195:134.

4. Koppen IJN, Vriesman MH, Saps M, Rajindrajith S, Shi X, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, Di Lorenzo C, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM. Prevalence of Functional Defecation Disorders in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr. 2018 Jul;198:121-130.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.02.029. Epub 2018 Apr 12.

5. Zar-Kessler C, Kuo B, Cole E, Benedix A, Belkind-Gerson, J. Benefit of pelvic floor physical therapy in pediatric patients with dyssynergic defecation constipation. 2019 Dig Dis https://doi.org/10.1159/000500121/

6. Chase J, Bower W, Susan Gibb S. et al. Diagnostic scores, questionnaires, quality of life, and outcome measures in pediatric continence: A review of available tools from the International Children’s Continence Society. J Ped Urol (2018) 14, 98e107

“What's wrong with children?”

As pelvic health physical therapists we take care of people suffering from bladder and bowel incontinence and/or dysfunction as well as pre-natal/ post-partum back pain, weak core muscles and pelvic pain. I was approached over 30 years ago by a urologist to take care of his pediatric patients. My reply: “What’s wrong with children?” It’s been a whirlwind of learning since that day!

Pediatric pelvic floor dysfunction is common and can have significant consequences on quality of life for the child and the family, as well as negative health consequences to the lower urinary tract if left untreated.

According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, by 5 years of age, over 90% of children have daytime bladder control (NIDDK, 2013) What is life like for the other 10% who experience urinary leakage during the day?

According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, by 5 years of age, over 90% of children have daytime bladder control (NIDDK, 2013) What is life like for the other 10% who experience urinary leakage during the day?

Bed-wetting is also a pediatric issue with significant negative quality of life impact for both children and their caregivers, with as much as 30% of 4-year-olds experiencing urinary leakage at night (Neveus, 2010). Children who experience anxiety-causing events may have a higher risk of developing urinary incontinence, and in turn, having incontinence causes considerable stress and anxiety for children (Austin, 2014; Neveus, 2010).

Additionally, bowel dysfunction, such as constipation, is a contributor to urinary leakage or urgency. With nearly 5% of pediatric office visits occurring for constipation (Thibodeau 2013, NIDDK, 2013), the need to address these issues is great! And, since pediatric bladder and bowel dysfunction can persist into adulthood, we must direct attention to the pediatric population to improve the health of all our patients.

Children suffer from many diagnoses that affect the pelvic floor including (Austin et al, 2014);

- Voiding dysfunction

- Enuresis (Bedwetting)

- Daytime urinary incontinence

- Urinary urgency and frequency

- Vesicoureteral reflux (Backflow of urine into the kidney)

- Pelvic pain (yes pelvic pain!)

The most common diagnoses I treat are voiding dysfunction and constipation. Pediatric voiding dysfunction is defined as involuntary and intermittent contraction or failure to relax the urethral muscles while emptying the bladder. (Austin et al, 2014); The dysfunctional voiding can present with variable symptoms including urinary urgency, urinary frequency, incontinence, urinary tract infections, and vesicoureteral reflux. Frequently, constipation is a culprit or cause. (Austin et al, 2014; Hodges S. 2012); Managing constipation can have a very positive effect on voiding dysfunction.

“What do we do to teach the pelvic floor (Kegel) muscles to work?”

Common questions I am asked include:

- Can I use biofeedback with children?

- Do we complete internal assessments on pediatric patients?

- How do we teach kids so they can understand?

- Do kids have the ability to learn strengthening versus relaxation?

- How do you teach a child to become aware of their pelvic floor and coordinate it?

If you have pondered these questions, let’s delve in! I see children as young as 4 who have been able to master biofeedback and recite back to me how their pelvic floor works with bowel and bladder function! Children are so eager to please and they love working with animated biofeedback sessions. The research supports the potential benefit of biofeedback training for children with pelvic floor dysfunction (DePaepe et al. 2002, Kaye 2008, Kajbafzadeh 2011, Fazeli 2014). The children are engaged and learn how to isolate their pelvic floor muscles (PFM) through positioning and breathing. The exercises are fun and easy to do. We also incorporate the core! What a wonderful opportunity we have to educate the younger population on these vital muscles as well as proper diet and bowel/bladder habits!

It is not typical to complete an internal pelvic muscle assessment on children, as this would not be appropriate.

“How do I treat it?”

In the literature on pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction you will often come across the word "Urotherapy". It is, by definition, a conservative management-based program used to treat lower urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction. (Austin 2014)

Basic Urotherapy includes education on the anatomy, behavior modifications including fluid intake, timed or scheduled voids, toileting postures and avoidance of holding maneuvers, diet, avoiding bladder irritants and constipation. Parents are often not aware of their children’s voiding habits once they are cleared from diaper duty after successful potty training occurs.

Urotherapy alone can be helpful however a recent study (Chase, 2010) demonstrated a much greater improvement in those patients who received pelvic floor muscle training as compared to Urotherapy alone.

The International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) has now expanded the definition of Urotherapy to include Specific Urotherapy (Austin et al, 2014). This includes biofeedback of the pelvic floor muscles by a trained professional who can teach the child how to alter pelvic floor muscle activity specifically for voiding. Cognitive behavioral therapy and psychotherapy are also important and can be a needed in combination with biofeedback in specific cases.

As you can see, PFM exercise combined with Urotherapy is a safe, inexpensive, and effective treatment option for children with pediatric voiding dysfunction.

Do bladder and bowel problems cause psychological problems or is the reverse true?

When we think of pediatric bowel and bladder issues, we primarily focus on what is happening to cause the bowel or bladder leakage and treat it accordingly. It is imperative to teach a child that she/he did not have an “accident”, but their bladder or bowel had a leak. It makes the incident a physiological problem and not something they did. See my blog post on “Accident” for more information.

It is not always apparent how much the child is suffering from issues with self-esteem, embarrassment, internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors or oppositional defiant disorders. Dr. Hinman recognized theses issues years ago (1986) and commented that voiding dysfunctions might cause psychological disturbances rather than the reverse being true. Dr. Rushton in 1995 wrote that although a high number of children with enuresis are maladjusted and exhibit measurable behavioral symptoms, only a small percentage have significant underlying psychopathology. In other more recent studies (Joinson et al. 2006a, 2006b, 2008, Kodman-Jones et al, 2001) it was noted that elevated psychological test scores returned to normal after the urologic problem was cured.

I frequently get testimonials from my patients. I would say the common denominator is the child and/or caregivers report that the child is “much better adjusted,” “happier”, “come out of his shell”, “more outgoing”, “making friends.” As a side note -- they’re happy they don’t leak anymore.

You can learn more about treating pediatric patients in my courses,

Pediatric Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders.

Austin, P., Bauer, S.B., Bower, W., et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescence: update report from the standardization committee of the international children’s continence society. J Urol (2014) 191.

Chase J, Austin P, Hoebeke P, McKenna P. The management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a report from the standarisation committee of the international children’s continence society. 2010; J Urol183:1296-1302.

Constipation in Children. (2013)retrieved June 9, 2014 from http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/uichildren/index.aspx

DePaepe H., Renson C., Hoebeke P., et al: The role of pelvic- floor therapy in the treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunctions in children. Scan J of Urol and Neph 2002; 36: 260-7.

Farahmand, F., Abedi, A., Esmaeili-dooki, M. R., Jalilian, R., & Tabari, S. M. (2015). Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercise for Paediatric Functional Constipation.Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research : JCDR, 9(6), SC16–SC17. http://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2015/12726.6036

Fazeli MS, Lin Y, Nikoo N, Jaggumantri S1, Collet JP, Afshar K. Biofeedback for Non-neuropathic daytime voiding disorders in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Urol. 2014 Jul 26. pii: S0022-5347(14)04048-8.

Hinman, F. Nonneurogenic neurogenic bladder (the Hinman Syndrome)-15 years later. J Urol 1986;136, 769-777.

Hodges SJ, Anthony E. Occult megarectum:a commonly unrecognized cause of enuresis. Urology. 2012 Feb;79(2):421-4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.10.015. Epub 2011 Dec 14.

Hoebeke, P., Walle, J. V., Theunis, M., De Paepe, H., Oosterlinck, W., & Renson, C. Outpatient pelvic-floor therapy in girls with daytime incontinence and dysfunctional voiding. Urology 1996; 48, 923-927.

Joinson, C., Heron, J., von Gontard, A. and the ALSPAC study team: Psychological problems in children with daytime wetting. Pediatrics 2006a; 118, 1985-1993.

Joinson, C., Heron, J., Butler, U., von Gontard, A. and the ALSPAC study team: Psychological differences between children with and without soiling problems. Pediatrics 2006b; 117, 1575-1584.

Joinson, C., Heron, J., von Gontard, A., Butler, R., Golding, J., Emond, A.: Early childhood risk factors associated with daytime wetting and soiling in school-age children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology2008; e-published.

Kajbafzadeh AM, harifi-Rad L, Ghahestani SM, Ahmadi H, Kajbafzadeh M, Mahboubi AH. (2011) Animated biofeedback: an ideal treatment for children with dysfunctional elimination syndrome. J Urol;186, 2379-2385.

Kaye JD, Palmer LS (2008) Animated biofeedback yields more rapid results than nonanimated biofeedback in the treatment of dysfunctional voiding in girls. J Urol 180, 300-305

Kodman-Jones, C., Hawkins, L., Schulman, SL. Behavioral characteristics of children with daytime wetting. J Urol 2001;Dec(6):2392-5.

Neveus, T, Eggert P, Evans J, et al. Evaluation of the treatment for monosymptomatic enuresis: a standarisation document from the international children’s continence society. J Urol 2010; 183: 441-447

Rushton, H. G. Wetting and functional voiding disorders. Urologic Clinics of North America, 1995; 22(1), 75-93.

Seyedian, S. S. L., Sharifi-Rad, L., Ebadi, M., & Kajbafzadeh, A. M. (2014). Combined functional pelvic floor muscle exercises with Swiss ball and urotherapy for management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a randomized clinical trial. European Journal of Pediatrics, 173(10), 1347-1353.

Thibodeau, B. A., Metcalfe, P., Koop, P., & Moore, K. (2013). Urinary incontinence and quality of life in children. Journal of pediatric urology, 9(1), 78-83.

Urinary Incontinence in Children. (2012). Retrieved June 9, 2014 from http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/uichildren/index.aspx

Zivkovic V, Lazovic M, Vlajkovic M, Slavkovic A, Dimitrijevic L, Stankovic I, Vacic N. (2012). Diaphragmatic breathing exercises and pelvic floor retraining in children with dysfunctional voiding. European Journal of Physical Rehabilitation Medicine. 48(3):413-21. Epub 2012 Jun 5.

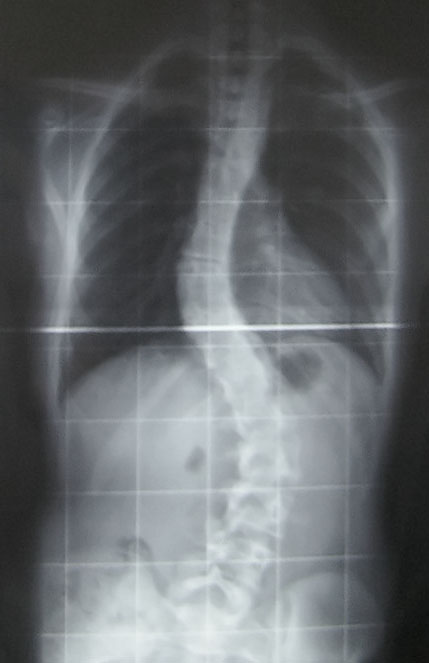

In some families, puberty is not only a time to have to deal with all the physical, hormonal, and emotional changes that are occurring, but it is a time to have to worry about and check for spinal abnormalities that can run in families. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is an abnormal curvature of the spine that appears in late childhood or adolescence. The spine will rotate, and a curvature will develop in an “S” shape or “C” shape. Scoliosis is the most common spinal disorder in children and adolescents. It is present in 2 to 4 percent of children between the ages of 10 and 16 years of age. There is a genetic link to developing scoliosis and scientists are working to identify the gene that leads to adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Adolescent girls are more likely to develop more severe scoliosis. The ratio of girls to boys with small curves of 10 degrees or less is equal, however the ratio of girls to boys with a curvature of 30 degrees or greater is 10:1. Additionally, the risk of curve progression is 10 times higher in girls compared to boys. Scoliosis can cause quite a bit of pain, morbidity, and if severe enough can warrant spinal surgery.

A recent article in Pediatric Physical Therapy by Zapata et al. assessed if there were asymmetries in paraspinal muscle thickness in adolescents with and without adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. They utilized ultrasound imaging to compare muscle thickness of the deep paraspinals at T8 and the multifidus at L1 and L4. They found significant differences in muscle thickness on the concave side compared to the convex side at T8 and L1 in subjects with scoliosis. They also found significantly greater muscle thickness on the concave side at T8, L1, and L4 in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis compared to controls. This is very interesting to me, and exciting to think about the possibilities of how we therapists might can use this information! My first question is, is the difference in muscle thickness a cause or result of the curvature of the spine? My next question is if we trained the multifidus on the convex side, the side that is thinner, would it make a difference in supporting the spine and therefore help prevent some of the curvature? Would strengthening the multifidus in a very segmental manner comparing right versus left and targeting segments and sides that are weaker than others help prevent rotation and curvature in individuals who have a familial predisposition to developing idiopathic scoliosis? I hope so! I hope this group continues to study scoliosis and provides some evidence-based treatment that can help decrease the severity of curvature.

A recent article in Pediatric Physical Therapy by Zapata et al. assessed if there were asymmetries in paraspinal muscle thickness in adolescents with and without adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. They utilized ultrasound imaging to compare muscle thickness of the deep paraspinals at T8 and the multifidus at L1 and L4. They found significant differences in muscle thickness on the concave side compared to the convex side at T8 and L1 in subjects with scoliosis. They also found significantly greater muscle thickness on the concave side at T8, L1, and L4 in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis compared to controls. This is very interesting to me, and exciting to think about the possibilities of how we therapists might can use this information! My first question is, is the difference in muscle thickness a cause or result of the curvature of the spine? My next question is if we trained the multifidus on the convex side, the side that is thinner, would it make a difference in supporting the spine and therefore help prevent some of the curvature? Would strengthening the multifidus in a very segmental manner comparing right versus left and targeting segments and sides that are weaker than others help prevent rotation and curvature in individuals who have a familial predisposition to developing idiopathic scoliosis? I hope so! I hope this group continues to study scoliosis and provides some evidence-based treatment that can help decrease the severity of curvature.

Assessing the multifidus thickness and strength, and differentiating it from the paraspinal muscles can be tricky. The best way to do this is the same way the authors of this article did, using ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound imaging gives unparalleled information on muscle shape, size, and activation of the muscle. Learning to use ultrasound imaging will change your practice! You will see dramatic differences in how you treat patients as well as the results you get when training the local core musculature. It also may open doors to treating different patient types than you are treating now, like adolescents with scoliosis. Join me in Spokane, WA on October 20-22 to further discuss how ultrasound can change your practice and perhaps help you reach out to a new population that you may not be treating now!

Miller NH. Cause and natural history of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:343–52.

Roach JW. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:353–65.

Zapata KA, Wang-Price SS, Sucato DJ, Dempsey-Robertson M. Ultrasonographic measurements of parspinal muscle thickness in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a comparison and reliability study. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2015; 27(2): 119-25.

After my Dad’s 3rd trip to the emergency room not being able to breathe because of his sleep apnea and congestive heart failure, his cardiologist recommended he ”just relax” when his suffocating feelings occurred. Of course, not being able to catch his breath would always heighten anxiety, which made it even more difficult to inhale and exhale. Ultimately, what my Dad needed to learn was mindfulness to deal with his relatively benign inability to breathe, since the focus of mindfulness is acceptance of rather than control over your circumstances.

The concept of mindfulness has been studied in adults, but it is gaining popularity among the pediatric population. Ruskin et al., (2017) used a prospective pre-post interventional study to assess how children with chronic pain respond to mindfulness-based interventions (MBI’s). For 8 weeks, 21 adolescents engaged in group sessions of MBI. Before, after, and 3 months post-treatment, the authors collected self-report measurements for a variety of factors such as disability, anxiety, pain quality, acceptance, catastrophizing, and social support. Subjects were highly satisfied with the treatment, and all would recommend the group intervention to friends. From baseline to 3-month follow-up, pain acceptance, body awareness, and ability to cope with stress all improved in the subjects. Further randomized controlled studies are needed, but the initial conclusion was MBI’s were received well by adolescents.

The concept of mindfulness has been studied in adults, but it is gaining popularity among the pediatric population. Ruskin et al., (2017) used a prospective pre-post interventional study to assess how children with chronic pain respond to mindfulness-based interventions (MBI’s). For 8 weeks, 21 adolescents engaged in group sessions of MBI. Before, after, and 3 months post-treatment, the authors collected self-report measurements for a variety of factors such as disability, anxiety, pain quality, acceptance, catastrophizing, and social support. Subjects were highly satisfied with the treatment, and all would recommend the group intervention to friends. From baseline to 3-month follow-up, pain acceptance, body awareness, and ability to cope with stress all improved in the subjects. Further randomized controlled studies are needed, but the initial conclusion was MBI’s were received well by adolescents.

A feasibility study performed by Anclair, Hjärthag, and Hiltunen in 2017 considered the effect of mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy for the parents of children with chronic conditions, looking at Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL), measured with Short Form-36 (SF-36), and life satisfaction. Ten parents received group-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and 9 participated in a group-based mindfulness program (MF). Treatment was implemented for 2-hour weekly sessions over the course of 8 weeks. The CBT treatment was based on the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, focusing on changing thoughts and emotions about stressful issues as well as behaviors. They avoided the acceptance aspect, as it would overlap the MF intervention. The MF therapy used the Here and Now Version 2.0 (including daily themes on knowing your body, observing breathing, acceptance, meditation, coping, understanding thoughts versus facts, and self-care reinforcement). The parents in each group significantly improved their Mental Component Summary (MCS), Vitality, Social functioning, and Mental health scores. The MF group even showed notable improvement in Role emotional and some of the physical subscales (Bodily pain, General health, and Role physical). The CBT group showed improved satisfaction with Spare time and Relation to partner, and CBT and MF groups improved life satisfaction Relation to child. The authors conclude CBT and MF may positively affect HRQOL and life satisfaction of parents with chronically ill children.

Whether young or old or in between, how we perceive stressful situations and chronic pain can impact our health. The neurodevelopmental aspect of mindfulness is still being studied. The “Mindfulness Based Pain Treatment” course applies the concept to treating chronic pain patients. This approach brings to mind the Serenity Prayer by Reinhold Niebuhr: “Lord grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Ruskin ,DA, Gagnon, MM, Kohut SA, Stinson JN, Walker KS. (2017). A Mindfulness Program Adapted for Adolescents With Chronic Pain: Feasibility, Acceptability, and Initial Outcomes. The Clinical Journal of Pain. http://www.doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000490

Anclair, M., Hjärthag, F., & Hiltunen, A. J. (2017). Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Mindfulness for Health-Related Quality of Life: Comparing Treatments for Parents of Children with Chronic Conditions - A Pilot Feasibility Study. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health : CP & EMH, 13, 1–9. http://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901713010001