The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society recently published recommendations for medical evaluation of women who have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI). The following steps are recommended for evaluation: history, urinalysis, physical examination, demonstration of SUI, urethral mobility assessment, and a post void residual. For women who have complicated SUI, urodynamic testing may be appropriate, according to the article, whereas in women with uncomplicated SUI, urodynamics testing may not affect treatment outcomes.

Uncomplicated urinary incontinence is defined within this article as including the following:

- • UI with loss of urine on effort, physical exertion, sneeze or cough

- • Absence of recurrent UTI

- • No prior major pelvic surgery including surgery for SUI

- • Absence of voiding symptoms such as urinary hesitancy, straining to void, spraying of stream, dysuria, sense of incomplete emptying, postmicturition leakage

- • Absence of medical conditions affecting lower urinary tract

- • Absence of vaginal bulge beyond the hymen, absence of urethral abnormality

- • Presence of urethral mobility

- • *<150 mL postvoid residual

- • Negative urinalysis

Recommended nonsurgical approaches include pelvic muscle strengthening (with or without physical therapy), behavioral modification, pessaries, and urethral inserts. The document also includes an example list of validated urinary incontinence questionnaires. The paper makes the point clear that "…counseling should begin with conservative options." However, for those women who wish to have a sling surgery, and "in whom conservative treatment has failed…" is a phrase used in the article, leaving us to wonder: what constitutes failed conservative care? Does this mean that a patient who has failed a pessary trial is a viable candidate for surgery? Or that someone who has completed pelvic muscle strengthening (and perhaps no behavioral modification therapy) should be considered a "failed" patient? Does it mean that a patient who was given a handout about completing Kegel exercises has completed a conservative bout of care?

Further guidelines can best be made when the research describing components of pelvic rehabilitation are included. Clearly the burden of responsibility falls on the shoulders of the pelvic rehab therapists to fill in this knowledge and/or research gap. Clinical guidelines are increasingly inclusive of pelvic rehabilitation approaches, which is a terrific improvement, and yet we should not like to see (with or without physical therapy) following pelvic muscle strengthening, particularly when clinically we see such a wide variety of pelvic dysfunctions limiting appropriate strengthening techniques.

For foundational information about evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, a therapist can begin with the Pelvic Floor level 1 training, and then continue through the pelvic floor series continuing education courses in which urinary incontinence is continually addressed as a topic.

This post was written by H&W instructor Lila Abbate PT, DPT, MS, OCS. Lila will be instructing the course that she wrote on "Coccyx Pain" in New Hampshire in September.

“Sit up tall, stand up straight” were comments we heard from our teachers and our caregivers. Do you find that you are saying that now to your patients? Postural correction can go beyond just preventing neck and low back pain. For a women’s health therapist, improved posture may help our patients prevent uterine prolapse or reduce coccyx pain.

Lind, Lucente and Kohn published a study back in 1996 titled Thoracic Kyphosis and the Prevalence of Advanced Uterine Prolapse. They determined that, in patients with uterine prolapse, the degree of thoracic kyphosis was about 13 degrees higher than in the 48 matched controls.1 Hodges, in the chapter titled “Chronic Low Back and Coccygeal Pain” in Clinical Reasoning for Manual Therapists, presents a case of a 39 year old woman with poor posture who has reproducible coccygeal pain, despite a coccygectomy, with palpation of her L4 segment. This poor posture perpetuates nerve and muscle dysfunction along with decreased and inappropriate muscle firing patterns that have created this long-term condition.

Whether our patients present with pelvic organ prolapse, chronic low back or coccygeal pain, it is important to step back and look at their overall posture. Decreasing thoracic kyphosis, or improving thoracic mobility, can help change an entire system. If you are looking for a course that takes you back to the basics and then enhances it with a twist of advanced techniques think about taking the Institute’s 2-day Coccydynia course.

References:

1. Lind LR, Lucente V, Kohn N. Thoracic Kyphosis and the Prevenlence of Advanced Uterine Prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Apr; 84 (4): 605-609.

2. Hodges P. Clinical Reasoning for Manual Therapists, Chapter 7, Chronic Low Back and Coccygeal Pain. Elsevier.2004; 103-122.

This blog post was written by faculty member Bridgid Ellingson, DPT, MPT, OCS, BCB-PMD. Bridgid is a private practice owner in the Chicago area and she is an instructor for the Institute's pelvic floor course series Level 2B course.

For years I resisted taking a physical therapy student into my clinic for their final rotation. The traditional physical therapy curriculum does not adequately prepare a student for the experience and I do not believe that physical therapy for the pelvic floor is entry level work. However, I recently had a particularly motivated student convince me to give it a try and I’d like to share my experience to help prepare other clinicians interested in taking students.

I first reached out to physical therapists in the community for advice- there were very few in the private clinic setting who had taken students. I was advised to interview the student to make sure she was a good fit. I was also advised to set realistic expectations with the student and the advisor- I could not guarantee how much hands-on experience she would get in my clinic. In the end, we agreed to a split clinical with the student in my clinic two days per week for ten weeks. This student had displayed entry level skills in previous clinicals and her advisor was not concerned that she would not be working independently or even with just supervision.

The next step was to prepare her for the clinical. The ideal scenario would have been to have her attend Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction and Treatment (Level 1) prior to the clinical, but the logistics did not work out for her. Instead she took two online continuing education courses: Functional Applications in Pelvic Rehabilitation Part A and B. She studied anatomy extensively and utilized many other internet resources. In my clinic, I prepared my clients by telling them that a special PT student with a strong interest in learning about pelvic floor rehabilitation would be working with me for the next ten weeks but that their care would not change and they always would have a choice as to whether to allow the student to observe or participate in treatment.

In the end, I feel that the clinical went quite well for me, the student, and my clients. The student was well prepared, respectful, professional, and had a good rapport with my clients. She was able to participate in history taking, health screening, orthopedic assessment, treatment planning, and documentation. Her ability to analyze data and formulate hypotheses and prognoses progressed well over the ten weeks. While she did not perform a pelvic floor examination on a client, she did bring in a “model” and I talked her through a complete pelvic floor examination. She did learn a variety of external treatment techniques and was exposed to the use of visceral manipulation, craniosacral therapy, trigger point dry needling, biofeedback, and rehabilitative ultrasound imaging specific to the pelvic floor. I believe that the after she gains hands-on experience by taking the Herman Wallace Pelvic Floor Series courses, she will be adequately prepared to start her career as a physical therapist specializing in pelvic floor disorders.

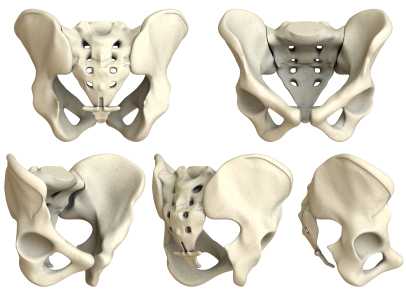

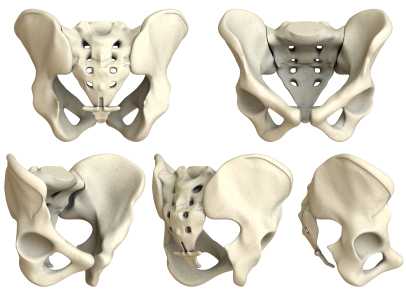

Are sacroiliac joint injections useful for our patient population? A 2013 review article, available here, concludes that current literature "…is unable to fully conclude the effectiveness of the modality and provide adequate comparison against surgical treatment." The above linked article provides a description of fluoroscopy-guided sacroiliac joint injections that can be used for both diagnostic and for therapeutic purposes.

According to the article, a guided injection may be indicated in a patient who has known sacroiliac joint pathology, a history of trauma, or referred symptoms into the buttock or lower extremity. Contraindications can include pathology of coagulation, pregnancy (due to radiation effects), systemic or local skin infection, or patient allergies to medication. During the procedure, a local anesthetic is utilized, and the patient is minimally sedated so that he or she is able to answer questions about pain. Both a pain-reducing medication and an anti-inflammatory are typically utilized; however, in patients who have received a maximum level of steroids, only an analgesic may be injected.

Results of an injection may include provocation of symptoms and/or immediate relief, which provides diagnostic value, i.e., that the structures injected may have, in fact, been causative to the patient's symptoms. For many patients, pain relief occurs within 24 hours. The long-term benefits of sacroiliac joint injections is not well-documented, so the ability to predict length of benefit is challenging.

In regards to rehabilitation of the patient who has undergone a sacroiliac joint injection, following a procedure, the patient is usually instructed to rest for 3-4 days and to follow-up with the referring medical provider within 2-3 weeks. The level at which a patient should resume physical activity, therapeutic exercises, and participation in physical therapy is determined by the medical provider. Level of activity in rehabilitation should therefore be coordinated with the patient's medical provider and potentially with the interventionist who performed the injection.

For more information about sacroiliac joint injections, check out this MedScape article about the topic, or clickhereto view a video of an SIJ injection. To learn clinical information about SIJ evaluation, mobilization, and stabilization activities, check out the next Sacroiliac Joint & Pelvic Ring Dysfunctioncontinuing education course taught by Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute faculty member Peter Philip. This course will be offered two times this year; coming up in early February on the West coast (Santa Barbara, CA) and in July on the East coast (Baltimore, MD.) Click here to learn more about the course objectives and schedule.

A recent study asked if transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can be a helpful treatment for men who have refractory chronic pelvic pain. 60 men completed pain diaries and the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) at baseline, after 12 weeks of TENS treatment, and at last known follow-up. The mean age of the subjects was 46.9 years. TENS was measured as an effective treatment in nearly half of the men, and the benefits of the treatment were sustained during a mean follow-up of 43.6 months in 21 of 29 patients. The primary measurement tool for pain, the Visual Analog Scale, or VAS, significantly decreased from 6.6 to 3.9. Quality of life measurement was also improved, with more men feeling mostly satisfied, pleased, or delighted versus dissatisfied, unhappy, or terrible.

What's the take home message? Regardless of the limitations of the study (non-randomized, non-placebo), TENS was found to be a safe and effective treatment without any adverse responses within this study. As a means of neuromodulation, which we know is critical in conditions of chronic pain, the application of electrotherapy is inexpensive, low-risk, and is a useful tool in the healing process. That healing process should include therapies that the patient can apply himself, so that he recognizes his own capacity and necessity for participating in recovery of function.

As there are few studies that address electrotherapy only for chronic pelvic pain, this research is useful in adding some weight to our clinical choices in modality use. Does a patient need to utilize TENS for 12 weeks to determine efficacy? Probably not, but this is an easy modality that can be trailed in the clinic, and utilized as a home program tool if recorded as beneficial for the patient.

The Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification test, or PRPC, is a certification that was developed to recognize expertise in the field of male and female pelvic rehabilitation. Until now, there is no other test available for therapists who wish to establish to their patients and to the community such expertise. As the applications come in to the Institute for review, one common question we hear is "How should I study for the exam?" There is no right answer to this question, as each therapist will need to decide what content areas of knowledge and skills are fresh versus needing an update.

The PRPC examination contents are broken down into 8 different domains. The 150 items or questions on the test will be based on these domains in the ratios shown below.

|

Anatomy |

22-23 items |

(15%) |

|

Physiology |

30 items |

(20%) |

|

Pathophysiology |

30 items |

(20%) |

|

Pharmacology |

7-8 items |

(5%) |

|

Medical Intervention & Tests |

7-8 items |

(5%) |

|

Tests & Measures |

15 items |

(10%) |

|

Interventions |

30 items |

(20%) |

|

Professional & Legal |

7-8 items |

(5%) |

When you consider the above categories, think of how each applies to pelvic rehab. In other words, while it may be helpful for you to have an exceptional knowledge base about the elbow, unless we are relating elbow anatomy, pathophysiology, or interventions to pelvic rehab, you can rest assured that items are not built around knowledge of the elbow. On the other hand, if a medical intervention, such as a surgery or medication, has an implication for pelvic rehabilitation, the examination can include such content. Topics that will not be directly tested on the examination include documentation, billing, the mechanisms of diagnostic testing such as urodynamics, marketing, or techniques outside of our scope such as prostate examination.

In terms of preparing for the certification test, upon approval of the application, a therapist will be sent documents that include information upon which the examination is built. The Job Tasks Analysis and the test Blueprint will be sent to the applicant, and the Blueprint contains more detailed topics within each of the domains listed in the above chart. Keep in mind that all topics were chosen through a rigorous process to represent the body of work in pelvic rehabilitation. There is no particular coursework that is required for this certification. You can be included on a list of participants interested in sharing contact details for a study group- this request is a part of the application process. The Institute also recently developed a page on the website listing resources that the pelvic rehabilitation provider may find helpful in locating sources of information. Keep in mind that this page will be continually developed, so check back often for links to articles and abstracts. For other questions about the PRPC examination, or to download an application, click here to access the website page for PRPC. Please contact the Institute directly by phone or email for any other questions.

Lumbopelvic and pelvic girdle pain (PGP) in pregnancy is estimated to occur in 20-30% of women, with prevalence as high as 50%. (Elden et al., 2013; Gutke et al., 2006; Mens & Pool-Goudzwaard, 2012; Ostgaard, 1991; Vleeming et al., 2008) One in four women who develop PGP in pregnancy develop chronic postpartum pain. (Ostgaard, 1991) According to Albert et al., 2006, risk factors for developing pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy include history of prior low back pain, back or pelvic trauma, high levels of stress, multiparity, and low job satisfaction. Non-risk factors include contraceptive medications, time since past pregnancy, height, weight, and smoking. (Vleeming et al., 2008) Fortunately, there is a trend for PGP to decrease within the first 3 months of delivery. (Elden et al., 2008) For pain that does persist, guidelines for treating pelvic girdle pain include providing individualized exercise prescription. (Vleeming et al., 2008) What type of individualized exercise or other intervention is appropriate?

A recent study by Elden and colleagues (2013) assessed the effect of including craniosacral therapy to standard treatment for pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain. In the multicenter, randomized, single blind, controlled trial, 123 patients were treated, with 60 in the control group and 63 in the intervention group. Standard treatment included education about the condition and anatomy of the back and pelvis, instruction in concepts of load demand and rest, activities of daily living advice, instruction in use of pelvic support belt, and exercises to stretch and strengthen the trunk, hip and shoulder muscles. Women in the intervention group received, in addition to the above, craniosacral manual releases to the pelvis. To see the program utilized, access the full article here.

Outcome measures included frequency of sick leave, morning and evening pain on visual analog scale, the Oswestry Disability Index scale, Disability Rating Index, European Quality of Life measure, intensity of discomfort of PGP, and blinded examiner assessment of recovery. The authors conclude the following: "Between-group differences for morning pain, symptom-free women and function in the last treatment week were in favor of the intervention group…treatment effects were small and clinically questionable…"

While craniosacral therapy is not strongly suggested based on the outcomes of this study, the authors acknowledge that craniosacral therapy is demonstrated in this and in previous research to have pain-relieving effects and a potential to halt deterioration of function. This type of clinical research model may prove to be very helpful in development of additional studies that assess the effects of specific interventions.

In my clinical and teaching experiences, and in the experiences of my colleagues, many therapists have questions about how to treat pregnant and postpartum conditions. It is common to encounter fears about working with patients who are pregnant due to the importance of avoiding potentially harmful examination and intervention techniques. We have also found that many therapists who are interested in women's health seek more information about orthopedic skills and practical clinical considerations. For these reasons, the Peripartum course series was developed over the past couple of years. Many of you may have taken the "Highlights of Pregnancy and Postpartum" taught by Institute founder Holly Herman, and will enjoy expanding your knowledge with the added days of coursework that includes both lecture and lab activities. The Institute offers a course based on pregnancy, one on postpartum, and a course on special topics during the peripartum period. The next opportunity to take the Pregnancy course is in January in Oklahoma City- there are still a few openings for this site.Join us to discuss issues such as pelvic girdle pain, what the evidence tells us, and what we can do for our patients.

References

Albert, H. B., Godskesen, M., Korsholm, L., & Westergaard, J. G. (2006). Risk factors in developing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. [Article]. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 85(5), 539-544. doi: 10.1080/00016340600578415

Elden, H., Hagberg, H., Fagevik Olsén, M., Ladfors, L., & Ostgaard, H. (2008). Regression of pelvic girdle pain after delivery: follow?up of a randomised single blind controlled trial with different treatment modalities. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 87(2), 201-208

Elden, H., Östgaard, H. C., Glantz, A., Marciniak, P., Linnér, A. C., & Olsén, M. F. (2013). Effects of craniosacral therapy as adjunct to standard treatment for pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women: a multicenter, single blind, randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

Gutke, A., Lundberg, M., Östgaard, H. C., & Öberg, B. (2011). Impact of postpartum lumbopelvic pain on disability, pain intensity, health-related quality of life, activity level, kinesiophobia, and depressive symptoms. European Spine Journal, 20(3), 440-448

Gutke, A., Östgaard, H. C., & Öberg, B. (2006). Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in pregnancy: a cohort study of the consequences in terms of health and functioning. Spine, 31(5), E149-E155.

Ostgaard, H. C., Anderson, G. B. J., & Karlson, K. (1991). Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy: A review (Vol. 16, pp. 95-101)

Mens, J., & Pool-Goudzwaard, A. (2012). Severity of signs and symptoms in lumbopelvic pain during pregnancy. Manual Therapy

Vleeming, A., Albert, H. B., Östgaard, H. C., Sturesson, B., & Stuge, B. (2008). European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal, 17(6), 794-819

Can patients successfully perform a pelvic muscle contraction following verbal instruction? This question was asked by Bump and colleagues in the often-cited research article published in 1991. Urethral pressure profiles were assessed in forty-seven women at rest and during a pelvic muscle contraction following brief, standardized verbal instruction. In the article, the authors found that nearly half of the women performed with "an ideal effort" leading to urethral closure without a Valsalva effort. 25% of the women, unfortunately, demonstrated an effort at muscular contraction that could promote incontinence. The authors' conclusion is that simple verbal or written instruction is not the best approach for a patient engaging in a pelvic floor muscle training program.

The limitations of the above study (small number of subjects, arbitrary definition of "effective Kegel," and inability to predict patient outcomes based on urethral profile) are made very clear throughout the article, yet how do we see this apply to our patient population? How often do we complete a perineal observation during an examination and identify that the patient is not generating any perineal movement, demonstrating a bearing down maneuver rather than a shortening, protective contraction, or creating such force through the abdomen that even a well-contracted pelvic floor would struggle against the strain from above? The value of the Bump study reminds us that not all patients respond positively to verbal or written instruction only.

What about men? A recent study aimed to assess the ability of 52 healthy men (mean age of 22.6 years with a standard deviation of 4.42 years) to complete a pelvic muscle contraction in standing or crook lying following brief, standardized instruction. Real-time transabdominal ultrasound was used to measure bladder base elevation. 6 participants were unable to contract the pelvic floor muscles in either position, 17 were unable to contract the muscles in crook lying, and 14 could not contract the muscles in standing. While many of the men we instruct in pelvic muscle rehabilitation strategies are significantly older than the men in this study, the major point matches that of the Bump article: it is not safe to assume that a patient (even a young, healthy patient) can contract the pelvic floor muscles following verbal instruction. The authors suggest that transabdominal ultrasound may be a useful clinical tool for measuring bladder base elevation and therefore pelvic muscle activity.

To be fair, more people in general need to be educated about the pelvic floor muscles;we can likely agree that the lack of awareness and discussion about the roles the PFM play in daily life leads to persisting dysfunction. There are people within the population who can activate the pelvic muscles appropriately with verbal instruction, and for this portion of the population, verbal or written instruction may be better than no instruction. Group education in community or institutional settings may benefit patients who are unwilling, unable or uninterested in acquiring a referral to a pelvic rehab provider. But for the group of patients who is either not contracting the muscles or bearing down rather than lifting, the consequences of doing pelvic muscle strengthening incorrectly may be significant. Do we need to change how we are instructing the patient verbally? Should we offer assessment of pelvic muscle contraction ability in varied positions? Must we include other functional applications of the coordinating muscles such as the respiratory diaphragm? At this time, there is not one answer. If we can ask the questions, read the research, and participate in our own way to the research, or at a minimum, apply these questions to clinical care, we may find the best answer for each individual patient.

The new PTPC exam, the first certification that recognizes specialized skills for

providers of pelvic rehabilitation, is available to the following activelylicensed practitioners:

- Physical Therapists (PT)

- Occupational Therapists (OT)

- Physician (MD, DO, ND)

- Registered Nurse (RN)

- Advanced Registered Nurse Practitioner (ARNP)

- Physician's Assistant (PA-C)

Applications from other providers will be reviewed for approval on a case by case basis to determine eligibility. The basic premise is that a provider must have a license that allows a provider to complete the appropriate examination and intervention techniques in order to sit for the PTPC exam. In addition to being a licensed provider, documentation of clinic hours must be included on the application. A minimum of 2,000 hours of clinical experience with pelvic therapy patients must have occurred over the last 8 years, with 500 of those hours occurring within the last 2 years. This patient care experience must be "direct" meaning that the provider is involved in processes that will have a direct influence on the patient such as examination, evaluation, designing or modifying plans of care, and interventions for pelvic conditions.

Conditions that relate to pelvic dysfunction may include, but are not necessarily limited to, the following conditions:

- Pelvic pain (dysfunctions of ligaments, bones, joints, connective tissues, organs)

- Pelvic girdle dysfunction

- Bowel dysfunction

- Bladder dysfunction

- Sexual dysfunction

- Abdominal dysfunction

- Thoracolumbar dysfunction

- Lumbo-pelvic-hip dysfunctions

The hours of direct patient care may include time spent with patients of various ages (elderly, adult, pediatric) or with patients of any gender. Please check out our page on the website that lists other frequently asked questions, and contact the Institute with additional questions. You can download the PTPC application here. The first exam will be given at the start of 2014!

The Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute is pleased to introduce pelvic rehab providers to the Pelvic Therapy Practitioner Certification (PTPC) application process that is now available on-line. The PTPC is the only certification that addresses specific knowledge and skills in the field of pelvic rehabilitation of men and women. The Institute has been working with Kryterion, an expert in exam development, since 2011 to accomplish the detailed and rigorous steps that go into a certification test. First, a job task analysis (JTA) survey was created with the work of subject matter experts (SME's) over a long planning weekend together. Many of you (403 to be exact) completed the lengthy survey to complete the development of this step. Through the JTA the Test Blueprint was created, upon which the test will be based.

Items on the exam were written by physical therapists who are clinicians and educators. Knowledge of patient care scenarios is integrated into the exam along with evidence based practice. Once all of the items were written, each was examined by a team of experts to be sure that the question meets the high standards of psychometrics and best practices.

This exam will allow a pelvic rehabilitation provider to achieve recognition for the years of study and practice required to develop his or her expertise. In the coming weeks we will continue to update our community about the PTPC application and testing process. As always, contact the Institute with any questions.