What are the spontaneous mental images that women who have chronic pelvic pain report, and how might the positive or negative mental images relate to chronic pelvic pain? These questions are the focus of research published by authors from the UK in the journal Pain Medicine. Mental images are distinguished in this study from thoughts, or thinking in words, as mental images are "cognitions with sensory-perceptual qualities." These qualities are often visual, and may also be related to smell, touch, taste, and hearing. Ten women were interviewed, 8 of whom had a diagnosis of endometriosis or adenomyosis. The researchers explained that they wanted to learn more about the women's thoughts when in pain, and asked about any images that popped into their heads when in pain. Researchers asked other questions about images related to specific categories, while attempting to avoid offering any leading words during their interview. The patients' most significant mental image (chose by the patient) was then explored for content, triggers, related emotion, meaningfulness, activity impairment, and related behavioral changes.

Other data collected included the Brief Pain Inventory short form, the Pain Catastrophizing Scale, the Spontaneous Use of Imagery Scale, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score, and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. The range of pain duration in the subjects was 3-20 years, with a mean age of 36.2. While every one of the ten women reported that pain was a trigger, other triggers for a negative mental image included movement, social gatherings, exercise, babies, anxiety, sex, sleep, talking about pain, and reminders of surgery or menstruation- in other words, common daily activities or experiences. The content of the most significant mental images included being raped, having "malicious demons" playing around the pelvis, bright lights in an operating room, being terrorized, feeling sad, helpless, anxious, angry, panicky, guilty, disgusted, horrified, and revulsed. The associated meanings were usually also quite negative in nature. The women reported active avoidance of the triggers when able, limiting activities such as social outings or physical activity. Positive or "coping" images were also reported, with images such as putting the pain into a box, mentally "rubbing pain" medication on the body, or imagining a loved one.

What does this information have to do with pelvic rehabilitation? This study utilized a cognitive-behavioral (CBT) framework, and aspects of CBT are tools that rehabilitation professionals utilize in daily practice. Simply put, a cognitive-behavioral approach addresses how a person's thoughts and feelings affect behavior. In rehabilitation, research studies have described how CBT is utilized in the physical therapy setting, and how therapists can be trained to use skills in CBT to help patients . We can engage patients in conversations about what negative images may be impacting movement, and what positive images may be utilized as healthy coping strategies. For more information about the mind and patient education, join us at Carolyn McManus's continuing education course Mindfulness-Based Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain which takes place next month in Seattle.

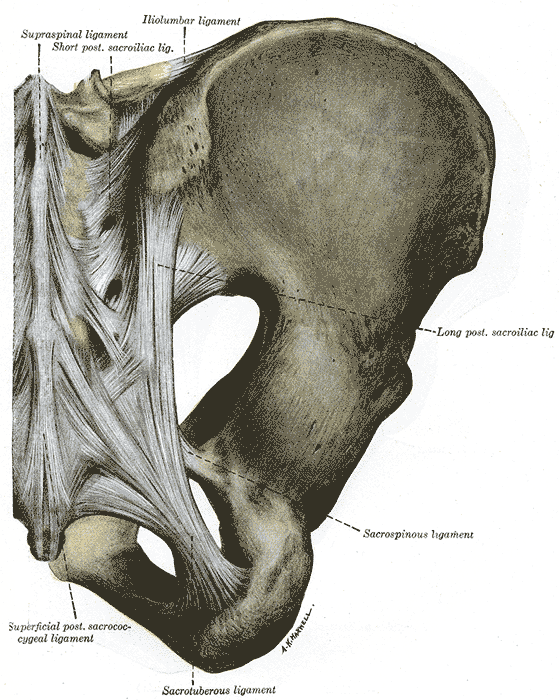

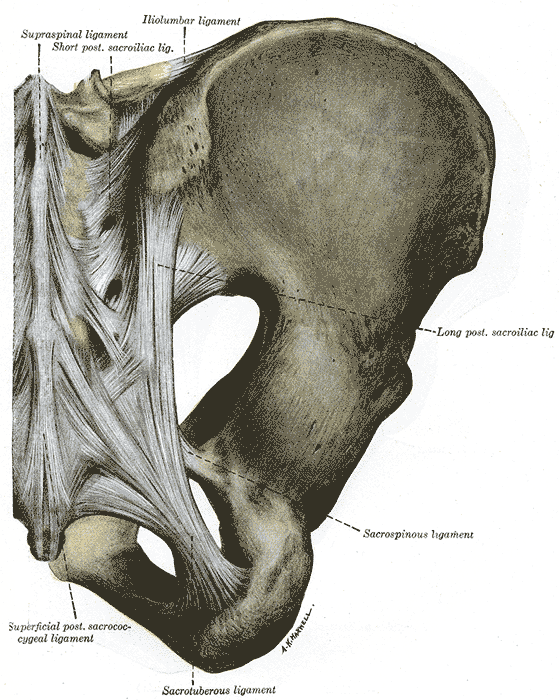

Several researchers have contributed to foundational literature in trunk control including Richardson, Snijders, and Hull. One study of interest completed by these authors and other colleagues assessed sacroiliac joint stability with contraction of the transversus abdominis muscles compared to contraction of all the lateral trunk muscles.

In this experiment, 13 healthy subjects without a history of low back pain participated in the tests. Eight men and five women with a mean age of 26 and who were able to complete the required muscle activations participated in the study. The subjects were positioned in prone, and electromyographic recordings as well as ultrasound imaging were used to verify the muscle activation patterns. To measure sacroiliac joint stiffness or laxity, Doppler imaging of vibrations was utilized. The theory of using vibration to measure joint stiffness includes that a transfer of vibration across a joint is best when the joint is more stiff, according to the authors.

The results of the study include a decrease in laxity (or an increase in stiffness) in the sacroiliac joint when either muscle patterns were used, however, when the transversus only was activated, laxity was decreased more than during a more global contraction.

Research in trunk and pelvic control has typically divided the muscles into local or global muscles, with inclusion of the the more superficial, larger muscles that control trunk movement grouped into the global muscles. Local muscles in this study describe the deeper, smaller muscles more apt to act as stabilizers of the lumbar spine and sacrum such as the transversus abdominis and multifidus. While this description is not inclusive of all or of more recent models, for the purposes of this study, these descriptions may be found useful.

The authors acknowledge that the role of the pelvic floor in creating sacroiliac joint stiffness, having not been measured, is not known in this study. The research does support the body of work that describes use of specific training for treating patients with low back pain, rather than global exercises without an emphasis on local muscle activation.

Many of you are aware of the various "camps" and beliefs about trunk and pelvic rehabilitation and activation, and more than likely, as with most issues in life, the truth lies in the middle. Do some patients simply need to correct their breathing patterns, trunk alignment, or gait patterns? Sure, and other patients may require a focus on inhibiting a very painful muscle, bringing awareness to that area, and learning how to "turn on" the muscle and incorporate the muscle pattern into routine activities. Herein we find, in my opinion, the art of rehabilitation. Researchers and therapists will continue to work towards clinical prediction rules and guidelines for best practice, yet we are left with understanding the theories and tools that drive the research and clinical practice so that we can apply individual plans of care for patients. If you find yourself "stuck" with the same "core" exercises and feel that you would like to improve your skills in sacroiliac rehabilitation, therapists have been raving about Peter Philip's sacroiliac joint course, where you can learn very specific palpation, testing, and rehabilitation principles. The next opportunity to take this course is in January!

The Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute is excited to offer continuing education courses this year in mindfulness and in meditation, which are not necessarily one in the same. However, each has a relationship with the other, and may be combined into lovely practices. More importantly, you may be wondering, "How does mindfulness fit into pelvic rehab?" Mindfulness or meditation has been applied to many pain diagnoses, and even to pelvic rehab conditions such as bowel or bladder dysfunction, and pelvic pain. (For some interesting reading about mindfulness and meditation, check out the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine's website by clicking here.

In this Canadian study, 14 women participated in four sessions of mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy tailored to women with provoked vulvodynia (PVD). The sessions were spaced 2 weeks apart, and each session was 2 hours in length. The program included education in PVD and in pain neurophysiology, cognitive behavioral skills ("identifying problematic thoughts"), progressive muscle relaxation (contract-relax), and mindfulness exercises. The mindfulness exercises included eating meditation, mindfulness of breath, body scan and mindfulness of thoughts. The goal of this particular research article was to describe the women's thoughts about participation in the study activities. The authors report on six major themes from the study:

1)Feeling more normal and part of a community in the group setting

2)Positive psychological outcomes

3)Impact of relationship (supportive versus unsupportive partner)

4)Feeling of gratitude for group facilitators

5)Concern about barriers to continuing their mindfulness practice

6)Feelings of self-efficacy in being able to exert control over their pain

One of the major themes expressed by the participants in this study is that of feeling more "normal" through finding out that other women have the same symptoms and knowing that there are a myriad of symptoms associated with vestibulodynia. By participating in the study, women reported having improvements in self-esteem and feeling more optimistic about their challenges with physical activities such as sexual relationships. Carloyn McManus, who has degrees in both physical therapy and psychology, shares her expertise in our new course: Mindfulness-based Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain. The next opportunity to take this mindfulness continuing education course, and learn skills that you can immediately apply in mindfulness is this November in Seattle.

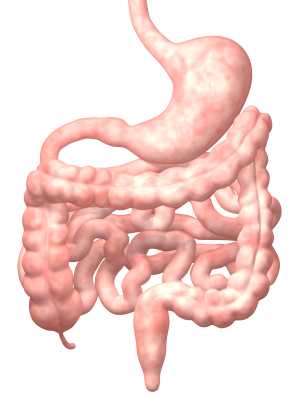

Consider how many times we have worked with a patient who refuses to participate in rehabilitation or cancels an appointment because of constipation. Also recall the high number of patients we treat who are in chronic pain and who are also likely taking an opioid medication for pain management. A well-known side effect of opioids is constipation, which can create a viscous cycle: taking the medication can mean having to strain to pass stool, or being bloated which can aggravate an already painful state. Not taking pain medications can increase pain levels, potentially decreasing physical activity levels, another cause for poor bowel function. A recent research article sheds light on this problem, pointing out that, despite a failure of medications in positively treating their constipation, patients are willing to continue on the current course of treatment.

The on-going longitudinal study in the USA, Canada, Germany, and the UK aims to assess the burden of opioid-induced constipation (OIC) in patients who have chronic pain that is not cancer-related. Patients were using at least 30 mg of opioids per day for more than four weeks and had self-reported opioid-induced constipation. For the 493 patients who met the inclusion criteria, retrospective chart reviews, on-line patient surveys, and physician surveys were utilized. Outcomes tools included the Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire-Specific Health Problem, EuroQOL 5 Dimensions, and Global Assessment of Treatment Benefit, Satisfaction, and Willingness to Continue. 62% of the patients were female, mean age in males and females was 52.6.

Patients complained of bowel dysfunction including abdominal pain and bloating, painful straining to defecate and having flatulence, rectal pain and bleeding, headaches, and having hard stools that were difficult to pass. Most of the patients (83%) wanted to have at least one bowel movement (BM) per day, yet the mean reported BM was 1.4 per week without use of laxatives, and 3.7 BM with use of laxatives. Natural or behavioral therapies were used by 84%, and 60% of the patients used at least 1 over-the-counter (OTC) laxative, 24% used 2 or more OTC laxatives, and 19% used one or more prescription laxatives. Unfortunately, 94% of the patients reported inadequate response to laxative use.

Current employment rates for the sample population was 27%, and of these patients, the average reports of missed work due to constipation issues was 4.6±11.9 hours of work over the past 7 days. Even worse, from a pain-management perspective, 49% of the patients reported "…moderate to complete interference with pain management resulting from their constipation." The authors conclude the following: "The prevalence of these symptoms suggests that patients may be undertreating their OIC and/or that the currently utilized therapies for the treatment of OIC may be lacking in efficacy and tolerability." Can we conclude that the under-treatment applies to a lack of pelvic rehabilitation intervention? Granted, opioid-induced constipation by nature of its effects on the gut will in turn affect peristalsis and hydration of stool. However, if a patient learns techniques to stimulate bowel activity, how to manage abdominal bloating and pain, and how to affect the nervous system in a positive way, perhaps less work (and leisure) time would be lost.

If you are interested in learning more about constipation, we have one opening in the PF2A St. Louis course taking place in early October. If you have already taken PF2A, and want to expand your knowledge and your skill set, join faculty member Lila Abbate in her Bowel Pathology and Function continuing education course in California in early November. Course topics include over-the-counter products and medications affecting bowel health, constipation and fecal incontinence, internal vaginal and rectal muscle mapping, and a balloon-manometry lab- a lab that therapists are thrilled to have offered in an Institute course!

An article this year in Canadian Family Physician concludes that "…pregnant women should avoid practicing hot yoga during pregnancy." Have you ever had a pregnant patient ask you if she should use hot tubs, warm pools, use hot packs, exercise in the heat, or participate in hot yoga? As always, the answer to some of the questions may be "it depends," as many factors must be considered including the woman's age, fitness status, pre-pregnancy exercise routines, general health, level of risk, what part of the body she wants to expose to heat, and ability to modify the requested activity. And, most importantly, the biggest driving factors behind our response to our patients is this: is there any known risk for the mother and her baby, and what does her physician say? If there is any known risk to the mother and to the viability of her pregnancy, then we always want to err on the side of caution.

What about yoga? Can participating in a hot yoga class increase core temperature and put the growing fetus at risk? The linked clinical reference article above cites some of the following factors as potential reasons why a person should not participate in hot yoga during pregnancy.

•Elevated core temperatures can occur with fever, extreme exercise, saunas, and hot tubs

•First trimester hyperthermia may lead to neural tube defects, gastroschisis, esophageal atresia, omphalocele, and encephaly in the developing fetus

•Heat decreases time to exhaustion, potentially leading to over stretching, muscle and joint injuries

•High temperatures may increase the risk of dizziness or fainting due to effects on blood pressure

I can imagine the arguments from all sides of the story, and we know that, especially in a highly litigious society, a medical provider will always suggest the most conservative approach. When the stakes are inclusive of both a healthcare license and the maternal/fetal health of our clients, rehabilitation professionals must also be medically conservative and mindful of the most safe, and effective health practices. Several prior posts have discussed the benefits of yoga during pregnancy, and the article by Chan and colleagues acknowledges that for pregnant women participating in yoga the benefits can include increased quality of life, decreased stress and anxiety, decreased pain, and improved sleep. Is it reasonable, then, to suggest that a woman avoid hot yoga during pregnancy?

If you are wondering, "What would Ginger say?", you have another opportunity to learn yoga principles and techniques applied during pregnancy from our yoga expert, Ginger Garner. Ginger teaches from the perspective of a mother, a physical therapist, an athletic trainer, a community educator, a national-level speaker, and a professional yoga therapist. She will be teaching the continuing education course Yoga as Medicine for Pregnancy in November in New York.

In an encouraging study sure to grab a lot of attention, researchers studying middle schoolers and the effect of mindfulness on suicidal thoughts have positive findings. We all know that middle school is a very challenging time, with students feeling pressure socially, academically, hormonally, and that family stressors can also be involved in this time of significant growth and change. If we think back to our time in middle school, we may recall some very challenging emotions, and a difficulty in seeing past our school environment and into our potential future. What if mindfulness training could provide an outlet for positive thoughts and a way to more effectively manage emotions?

In this study, highlighted in the research spotlight of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 100 sixth graders were randomized into an Asian history class with daily mindfulness practice and into an African history class with a matched activity unrelated to mindfulness or self-care. The mindfulness instruction included breath awareness and breath counting, body sensation, thoughts, and emotions labeling, and body sweeps. Silent meditation increased from 3 minutes to 12 minutes. Over the study period of 6 weeks, students were assessed for development of suicidal thoughts or self-harm behaviors.

While the researchers conclude that more studies with larger groups need to be done to validate the findings, the reports of this study are very encouraging. Keeping in mind that there are no equipment needs and little or no risk with the applied intervention, perhaps more schools will look to trainable skills in mindfulness to teach young people self-management skills. Mindfulness and meditation continue to receive significant attention in the research literature, and rightly so, as patients, providers, and family members may benefit from simple techniques that can be practiced and applied in a variety of ways.

If you would like to learn more about how to practice and to teach skills in mindfulness, sign up early for our new continuing education course called Mindfulness-based Biopsychosocial Approach to Chronic Pain. Instructor Carolyn McManus has been studying, practicing, and teaching mindfulness to patients and providers for many years. This course can be taken by any health provider, so invite your colleagues to join you at the course! If you are not yet familiar with her work or her patient resources, you may find her guided meditation and relaxation CD's a terrific tool to share or utilize yourself. You can listen to samples of the work on her website by clicking here.

One thing I have decided after working with women during and after pregnancy is this: babies come when they want, and how they want to arrive. A mother's best laid birth plans will hopefully have enough flexibility to allow her to feel successful even if, and especially if, her plans have to change. A fundamental question that has been asked, from the standpoint of a mother's beliefs is, do women really feel they have a choice to deliver at home versus in a hospital?

Researchers in the UK asked this question of a diverse sample of 41 women who were interviewed. Despite the fact that in the UK, a woman can birth at home with a midwife (and this is covered by the National Health System) home births are unusual, accounting for only 3% of all births. And while it may seem exciting to read that in the US, the number of home births has risen by more than 50% over a decade, the actual numbers include that less than 2% of births occur at home according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) data.

Back to the concept of choice, when women were interviewed about where they planned to give birth, perceptions rather than fact ruled the day. The concept of which environments were "safe" versus "risky" were a common theme, with women having differing explanations of why a hospital might be more safe than the home environment, or vice versa. The authors describe the issue that, when healthy mothers with low-risk pregnancies give birth in hospital environments, medical interventions including surgical birth are more likely to place. Women who would choose a home birth reported beliefs such as not being able to have a 'natural' birth in a hospital, fear of contracting illness or disease, or of wanting to be at home surrounded by loves ones. Women also reported that at home, more control over the environment and increased ability to relax would be available.

On the other hand, women who wanted to give birth within a hospital associated the medical environment with safety and reassurance, and expressed fear of feeling guilty if events did not turn out well with a home birth. Unfortunately, some women reported feeling "unfit" to give birth and chose the hospital as a place where both mother and the baby would be more safe. This, I believe, is a very sad statement about the disempowerment that women feel in relation to their own ability to feel healthy and strong in their own body, and to trust that the birth experience can progress well in a multitude of environments. Women interviewed in the study cited marketing and propaganda as contributing to a sense of not being healthy or fit enough to manage the birth outside of a hospital.

The authors point out that "…beliefs and assumptions about birth risk are deeply ingrained…" and that fear of the risks of birthing at home, well-founded or not, remain prevalent. So what is our role? Perhaps to share that healthy women who have uncomplicated pregnancies have choices, and that we believe in their ability to make positive, strong choices that their bodies are fit to perform. There are many birthing centers that are designed with home comforts, and that offer a "middle ground" between a hospital center and a home environment. Home births can be attended by well-trained midwives or other practitioners who are experienced in knowing when and how to access more interventional approaches if needed. This post is not about whether a woman should give birth at home or in a hospital- that issue is hotly debated by many forums currently and by experts in the topic. What we as pelvic rehabilitation providers can continue to offer is coaching, encouragement, and education that is empowering to a woman, so that when she makes a decision (in conjunction with her chosen providers) about how she would like the birth of her child to be achieved, she feels "fit" to birth in the environment she chooses.

If you agree that we have a role in providing a platform from which we educate and empower women to trust their bodies and their choices about birthing, then you will L.O.V.E taking a course with Ginger Garner, a very empowered (and empowering) woman who is a relentless advocate of these issues. In New York, in November, you can take Ginger's continuing education course Yoga as Medicine for Pregnancy. Watch for future Yoga as Medicine courses from Ginger to be updated on our schedule in the coming weeks. Can't make a live course right now? Check out Ginger's online courses with Medbridge, and take advantage of the Herman Wallace discount on our website!

A recent article describing the impact of psychological factors on bowel dysfunction describes several mechanisms by which this may occur. Issues cited that may influence the bowels include psychological stress, which can lead to nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and changes in bowel patterns or habits. Stress can also affect the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, or HPA axis. This axis is a major part of the neuroendocrine system that, in addition to controlling stress reactions, regulates many body functions such as digestion and immunity. During stress, cortico-releasing factor (CRF) can also be released, and act directly on the bowels or via the central nervous system. The authors point out that CRF can also affect the microbiota composition within the gut.

Corticotrophin-releasing factor can affect gut motility, permeability, and inflammation. The way in which motility is affected can vary, from increased movement of bowel contents to more sluggish movement, depending "…on the type of CRF family receptor expressed on the target organ." Gut permeability can also be affected by CRF, leading to bowel hypersensitivity and other issues such as nutritional absorption dysfunction. Stress-associated inflammation is also of concern, with markers of inflammation being found in patients who have irritable bowel syndrome and other conditions. Dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance, can be caused by stress, leading to changes in bowel motility , inflammation, and permeability, according to the referenced article. Diet-induced dysbiosis, discussed in this article, can lead to inappropriate inflammation and to cellular damage and autoimmunity, making a person vulnerable to chronic disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Such disease conditions may include ulcerative colitis, Chrohn's disease, celiac disease, and diabetes. Probiotics, prebiotics, and alterations in dietary intake are current therapeutic approaches, with further research needed to determine what types of interventions are most helpful for specific conditions.

Pelvic rehabilitation providers, especially those who are newer to the field, quickly discover that trying to treat pelvic dysfunction without knowledge of bowel health is like trying to treat low back pain while ignoring the pelvis: to truly ease symptoms both may need to be addressed. Patients often present with a combination of issues in the domains of bowel, bladder, sexual health and pain, and being able to address all with expertise aids in effectiveness of care. If you are interested in learning more about bowel dysfunction, faculty member Lila Abbate teaches her continuing education course "Bowel Pathology and Function" in California in early November. There is also an opportunity to learn about how to ameliorate stress and its potentially negative affects on bowel health by attending the Mindfulness-Based Biopsychological Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain taking place in Seattle in November.

According to the APTA's Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, physical therapists use a systematic process, also termed differential diagnosis, to place a patient into a diagnostic category. This diagnosis is aimed towards defining the dysfunctions that will be treated, and in determine the needs of the patient based on each individual's presentation. Rehabilitation professionals must also consider symptoms and clinical examination findings that point to a need for other health care providers' involvement. In pelvic rehabilitation, this becomes a challenging process. In an article in Canadian Family Physician, physicians Bordman & Jackson list conditions that can cause chronic pelvic pain, and these conditions cover a variety of body systems and conditions. For example, bladder, bowel, or gynecologic malignancies, endometriosis, pelvic congestion, interstitial cystitis, urethral syndrome, constipation, inflammatory or irritable bowel syndrome can all cause pelvic pain. Abdominal wall or pelvic floor muscle myofascial trigger points, coccyx pain, neuralgia, and even depression can be other sources for pain. Certainly, it is uncommon to find only one source of pain in our population of patients with chronic pelvic pain.

Within a multidisciplinary approach, which is more often the recommended approach to treating chronic pelvic pain, physical therapy will ideally work with other practitioners to develop the best course of care for the patient. In my professional experience mentoring students and therapists, once a pelvic rehabilitation provider has learned basic skills and has treated many patients, the therapist develops a keen interest in improving skills of differential screening. The ability to diagnose requires learning which keys unlock certain doors, whether from an organs systems standpoint or a musculoskeletal standpoint. The Institute offers several courses that focus on the ability of a therapist to test specific tissues and movement patterns to determine the most appropriate plan of care. Steve Dischiavi's Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip and Pelvis includes a sports medicine approach to evaluating and treating hips and pelvic dysfunction, which can often confound one another. Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain is another popular course instructed by faculty member Elizabeth Hampton and the course emphasizes pelvic pain and the musculoskeletal co-morbidities that often accompany pelvic floor dysfunction. More dates are being scheduled for these 2 continuing education courses, sign up early to hold your spot!

You still have an opportunity to take Peter Philip's Differential Diagnostic of Chronic Pelvic Pain & Dysfunction this course takes place in Connecticut in mid-October. In this course, Peter emphasizes anatomical palpation, nervous system influence on pelvic pain, and biomechanical examination of nearby joints and tissues. Internal labs are included in this 2-day continuing education course. If you are interested in hosting any of these courses, contact the Institute today to get the process started!

Male chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is well-known to be associated with sexual health impairments including, but not limited to, pain limiting sexual activity, premature ejaculation, erectile dysfunction. In addition to potential interference in sexual activity due to pelvic pain associated alteration in libido and function, does CPP affect sperm health? According to a systematic review and meta-analysis published this year, semen parameters are impacted in men who present with chronic pelvic pain. 12 studies were utilized, including nearly 999 cases and 455 controls. Semen parameters studied included seminal plasma volume, sperm concentration, total sperm count, motility, vitality, and morphology. Men diagnosed in the studies with CPP or chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) met the NIH criteria for the condition.

The results of the analysis indicate that sperm concentration, percentage of progressively motile sperm, and morphologically normal sperm in patients with CPP/CPPS were significantly reduced when compared with controls. Semen volume was higher in the CPP pain group than in controls, and the results suggested no significant difference in sperm total motility, sperm vitality, and total sperm count. How do these factors affect fertility? The authors point out that semen parameters are "the mainstay of male fertility and reproductive health assessment" and and that the percentage of morphologically normal sperm is an indicator of male fertility potential. While the sperm concentration was identified to be lower in male patients who have CPP, the semen volume being elevated may affect these numbers. Sperm motility, being necessary for fertilization, would logically be a factor in potential impairment of fertility.

The authors discuss the possibility that an inflammatory response associated with chronic pelvic pain, or an autoimmune response against prostate specific antigens factor into the alterations in semen analysis observed in men who have chronic pelvic pain. While the issue of fertility and pelvic pain is controversial, and not entirely understand, we can hypothesize about local factors affecting pelvic and sexual health, as well as autonomic nervous system implications mediated by the chronic pain state. As science aids in the understanding of the mechanisms affecting semen parameters, pelvic rehabilitation professionals will continue to address the potential causes of the dysfunction: nervous system dysfunction such as anxiety, depression, hormonal regulation, and neuromuscular pain states that may affect local blood and lymph flow (and therefore affect cellular nutrition and removal of waste products of cellular metabolism). If you are interested in learning more about male anatomy, sexual dysfunction, pelvic pain, and incontinence, come to the Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction, & Treatment continuing education course in Tampa in October!