In our weekly feature section, Pelvic Rehab Report is proud to present this interview with Herman & Wallace instructor Ginger Garner, PT, MPT, ATC.

How did you get started in pelvic rehab?

My entry point into pelvic rehab was a bit unorthodox and as a result, my colleagues at the time (back in the 90’s), considered my practice quite eccentric and frankly, a bit strange.

In fact, although I can see lots of humor in it now, I was actually pushed out of a practice because what I was doing was “too individualized” and patient specific. Of course, that “eccentric” entry point into pelvic rehab was integrative medicine, using a yoga-based biopsychosocial model of practice.

Who or what inspired you?

To answer that question I think you first have to be able to recognize and appreciate times when you have not been well supported or inspired, kind of like having to know adversity before you can recognize and value success.

Here’s my short story:

Early on in my education (in sports medicine, athletic training, physical therapy, yoga, and pilates) I realized that the biomedical model, although stellar at handling life-threatening emergencies, was not always so great at addressing chronic conditions and preventing disease processes and injury. So the answer to what inspires me – is the privilege of being able to be on the prevention end of injury and disease.

Back in the 90’s, I had a faculty instructor who encouraged me to keep pursuing my passion – in spite of the pushback I got from many directions, including within the department at the university. She found a way for me to pursue lateral work in the School of Public Health, which I felt was necessary in order for me to become a successful patient advocate. It was a great experience where I was able to work with the Governor’s Council on Physical Fitness and Health and conduct a pilot study. Her encouragement inspired me to keep following my dream, which is why I strongly believe in this quote by Mark Twain,

“Keep away from people who try to belittle your ambitions. Small people always do that, but the really great make you feel that you, too, can become great.”

Fast forward almost 20 years, and my most influential mentors, sources of my biggest inspiration, have been 1) Dr. Riane Eisler, holocaust survivor, attorney, social scientist, and founder of the not-for-profit organization, Caring Economics, which works to end violence against women and raise the status of caregiving; and 2) my three children. Experiencing pregnancy three times was an enormous gift, which allowed me the privilege giving birth not just to my three boys, but also to the framework for using yoga in prenatal, childbirth, and postpartum to prevent and manage injury and pain. The mothers I work with also inspire me. The work I do is for them and their future children.

What have you found most rewarding in treating this patient population?

There is go greater reward than empowering women, especially mothers and mother-to-be.

Women are too frequently disempowered by our current medical model. Their concerns are often marginalized and the care they get can be dehumanizing and humiliating, especially during maternal and childbirth care. I believe that above being a physical therapist, an athletic trainer, and an integrative clinician, I am first and foremost a patient advocate. Each woman I work with is a personal investment of my time, energy, and dedication. The reward of seeing a woman be able to pursue the compassionate birth she wants and deserves, to find relief from pelvic pain, and to know what questions to ask to get the best care from her health care providers, all because of the time I have spent with her – is worth more than gold.

What do you find more rewarding about teaching? (this could be one story or something you always find magical about the experience)

The two most rewarding aspects of teaching are 1) changing the course and paradigm of practice in rehab and medicine by fostering creativity and a shift toward person-centered, integrative practice, and 2) getting to be constantly immersed in research.

I love learning and am the perpetual student. I’m currently working toward my doctorate at UNC Chapel Hill, and love the interchange and partnership that is nurtured by being in education.

What trends/changes are you finding in the field of pelvic rehab?

The full circle return to seeing the person as whole, and not broken or as a part, is incredibly encouraging.

I am seeing this through the integrative courses that H&W is embracing, including my own courses in yoga, but also and perhaps more importantly, through the ground swell of individual health care consumer action. Folks realize “health care” doesn’t just consist of drugs and surgery, and they are seeking out integrated care now more than ever. Still yet, access to pelvic rehab can be vastly improved, which is a great segue into the next question.

If you could make a significant change to the field of pelvic rehab or the field of PT, what would it be?

As a patient advocate, I believe our biggest responsibility as clinicians is to improve access to pelvic rehab and integrated care.

Integrated care I define as “integrative medicine + rehab.” PT’s are not yet the practitioner of choice in many areas, including back and pelvic pain and orthopaedic injury. So we have our work cut out for us – to improve public health education and health literacy about physical therapy and specifically, pelvic PT.

If I had the chance, I would absolutely become involved in evolving the scope of practice and increasing the reach and influence of PT on a legislative and policy level.

What have you learned over the years that has been most valuable to you?

Relationship is more important than anything else.

You can be the most skilled clinician on the planet, and plan the best integrated, “wholistic” biopsychosocial plan of care the world has ever seen – and yet, if you haven’t connected with the patient and nurtured a therapeutic landscape that fosters compassionate care and a safe environment, then patient outcomes will falter. What’s more is, patient frustration and clinician burnout will be high.

When in doubt about what you are doing, return to nurturing relationship.

What is your favorite topic about which you teach?

My courses are like my children. I can’t choose a favorite. I love teaching integrated hip labral care, because it’s difficult and complex subject matter and urgently needed in this rapidly developing new field of hip rehab. But I equally love helping women toward the pregnancy and birth they desire and deserve.

Overall, no matter what the course is, yoga is the entry point for the zen I experience when teaching, practicing integrated physical therapy, and in my personal life. Ultimately, guiding my students and patients toward their own version of that mountain-top experience of personal and professional transformation – that is the real deal.

Ginger Garner, PT, MPT, ATCOther Credentials: PYT, ERYT500, CPI

GingerGarner.com

H&W Courses: HLI, YPREG, YPOST

Update: Please note that this course is now only offered online through the instructor's website. For more information visit https://pelvicpainrelief.com/laser/

Herman & Wallace is announcing a new course on laser therapy for pelvic pain! The Pelvic Rehab Report caught up with the instructor, Isa Herrera.

Laser Therapy For Female Pelvic Pain was developed by Isa Herrera MSPT, CSCS for Herman and Wallace specifically for women’s health clinicians. Ms. Herrera is the author of 4 books, including the breakthrough book, Ending Female Pain, A Woman’s Manual, now in its 2nd Edition. Ms. Herrera has appeared on several national TV and radios shows including on MTV True Life, The Regis and Kelly Show and NBC’s Today Show. She lectures nationally on the topic of women’s health and has been a passionate advocate about pelvic health for over 10 years.

Can you describe the clinical/treatment approach/techniques covered in this continuing education course?

Laser Therapy For Female Pelvic Pain Conditions (LTFPP) is a two-day intensive course that provides the clinician with hands-on experience and treatment protocols using low level laser for the relief female chronic pain conditions that include vestibulodynia, vaginismus, bladder, coccyx and scar pain.

“This class is one in which pelvic floor therapists bring their foundational knowledge of anatomy, neurology and previous training and learn to apply it to laser therapy. “ says Ms. Herrera. “In this class I will share with you my treatment protocols that I have used at my healing center for the last ten years. These treatment protocols are safe and help provide pain relief, reducing injury damage and loss of function. Your patients will oftentimes see immediate results,” she continued.

What inspired you to create this course?

“Clinicians deal with female chronic pain on a daily basis that can be problematic to treat and manage. There is an arsenal of tools, exercises and techniques at their disposal, but many times using a proven modality can help to accelerate the pain-relieving process for the patient. I created this course not only to help the women out there who suffer everyday with debilitating pain, but also to help clinicians achieve even more success with their treatments.”

What resources and research were used when writing this course?

- Atlas Of Clinical Anatomy-Frank Netters

- Grays Anatomy

- Ending Female Pain, 2nd edition, Isa Herrera

- Herman and Wallace PF 1, PF2, PF3

- V Book by Elizabeth G. Stewart and Paula Spencer

- Travell and Simmons Volume 2. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. The Lower Extremities

- Current Research Articles on Low Level Laser Therapy

Why should a therapist take this course? How can these skill sets benefit his/ her practice?

“This class is for the clinician that is working in the field of women’s health and who typically treats female chronic pain conditions. Clinicians looking for a non-invasive modality, one that is easy to operate and provides reliable and effective treatment options, will see great value in this course. This course provides the clinician with protocols and applicable information on the safe usage of low level laser therapy for female pelvic pain,” says Herrera.

With words like jumping, diving, spiking, hitting, and blocking making up the game's activities, volleyball is clearly a sport that requires a healthy pelvic floor. We know that athletes are at risk for pelvic dysfunction, with symptoms ranging from tension to leakage, but what happens when the pelvic floor is reeducated? In a study addressing volleyball players, researchers assess the effectiveness of a pelvic muscle rehabilitation program on symptoms of urinary incontinence. 32 female athletes were divided evenly between a control group and an experimental group. Inclusions criteria for the sample was nulliparity, symptoms of stress urinary incontinence, age between 13 and 30, and leakage amount more than 1 gram on the pad weight test. Exclusion criteria is as follows: treatment time of less than six months, sport practice for less than two years, urinary tract infections (either current or repeated prior infections), intervention adherence less than 50%, or body mass index outside of the range of 18-25.

Before and after intervention, the athletes were given a baseline questionnaire, a pad test (in the first 15 minutes of volleyball practice), and they completed seven days of a bladder diary to track leakage. The treatment group were instructed in anatomy and physiology of the lower urinary tract, about urinary incontinence (UI) and UI in athletes, and in leakage prevention strategies. A 3-day bladder diary was completed to improve awareness of fluid intake and bladder habits. Pelvic muscle awareness and correct contractions, doing protective pre-contractions of the pelvic floor, and a home exercise program of quick and endurance pelvic muscle contractions in different positions were also instructed.

The results of the intervention include a significant decrease in urinary leakage in the treatment group. The education provided also allowed for prevention of negative coping strategies that were reported in the subjects: the athletes would conceal leakage by wearing a menstrual pad, decreased their fluid intake, or empty their bladder more frequently. This study contributes to the growing body of evidence linking sport to pelvic dysfunction, and more importantly, rehabilitation efforts to improvement. If you want to learn more about pelvic dysfunction in athletes, come to The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor with Michelle Lyons. This 2-day continuing education course took place recently in New York City and your next opportunity to take the class is in Denver in October!

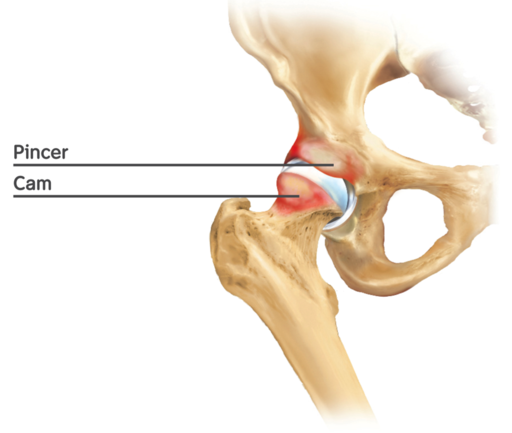

In the treatment of pelvic dysfunction, collaboration among physicians and pelvic rehabilitation providers creates an optimal care situation for the patient. In a research article that will be published in the July issue of Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, physical therapist and Herman & Wallace Institute faculty member Stacey Futterman demonstrates how a partnership between disciplines provides information valuable to the field of pelvic rehabilitation. Stacey and physicians Deborah Coady, Dena Harris, and Straun Coleman hypothesized that persistent vulvar pain may be generated by femoroactebular impingement (FIA) and the resultant effects on pelvic floor muscles. Through the research, the authors attempted to determine if hip arthroscopy was a beneficial intervention for vulvar pain, and if so, which patient characteristics influenced improvements.

Twenty six patients diagnosed with generalized, unprovoked vulvodynia or clitorodynia underwent arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement. For 3-6 months following hip repair, patients were treated with physical therapy that included surgical postoperative rehabilitation combined with rehabilitation for vulvodynia. Time period for follow-up data collection ranged from 36-58 months. Six patients reported improvements in vulvar pain following surgery and did not require further treatment, and it is noted that these patients were all in the youngest age bracket (22-29). Among the patients who did not report sustained relief, relatively older ages (33-74) were noted, along with a tendency to have vulvar pain for 5 years or longer.

The relationship between hip and pelvic pain may come from the bony structures, hip muscles including but not limited to the obturator internus, and nerves such as the pudendal. The authors conclude that "All women with vulvodynia need to be routinely assessed for pelvic floor and hip disorders…" and if needed, treatment should be implemented to address the appropriate tissue dysfunctions. If you are interested in learning more about hip dysfunction so you can better screen for dysfunction such as femoroacetabular impingement, check out faculty member Steve Dischiavi's continuing education course. Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis: Manual Movement Therapy and the Myofascial Sling System takes place next in Durham, North Carolina in May.

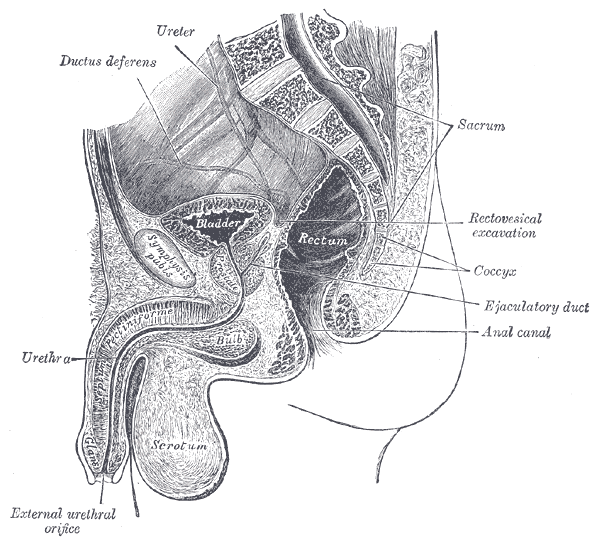

Patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer may undergo a procedure called mesorectal excision as part of their oncology management. In this procedure, a significant portion of the bowel is removed along with the tumor. Total mesorectal excision refers to the entire rectum and mesorectum (peritoneum that connects the upper rectum.) The rectum is removed up to the level of the levator muscles, and this procedure is indicated for tumors of the middle and lower rectum. In a study published in the World Journal of Oncology, the authors report on female urogenital dysfunction following total mesorectal excision (TME).

Questionnaires were returned by 18 women (age range 34-86) who had undergone TME for rectal cancer. Results of the study are summarized in the chart below. (All patients had reported vaginal childbirth, and five had undergone total abdominal hysterectomy and oophrectomy.)

| Presurgical

|

Postsurgical

|

Sexual function

| 5/18 (28%) were sexually active (with no complaints of dyspareunia) | Sexually active patients remained active but all reported discomfort with penetration 2 patients reported decreased libido due to stoma |

Urinary function

| 3/18 (17%) reported urinary urgency and frequency | Of patients with urinary symptoms, 80% persisted longer than 3 months post-surgery |

| 7/18 (39%) reported stress urinary incontinence | |

| New onset symptoms: 61% developed nocturia, 20% developed stress urinary incontinence, 1 patient required permanent catheter |

The authors conclude that rectal cancer treatment can worsen urinary symptoms of nocturia and stress incontinence. Patients who had also been treated with a hysterectomy were found to have more significant symptoms. A proposed mechanism of this increase in symptoms in women who had undergone a hysterectomy is the prior nerve dissection which, when added to the nerve dissection of the inferior hypogastric plexus and the hyogastric nerves for the total mesorectal excision, may have an additive effect. This study which is available full-text, free access, describes further the relationship between the autonomic nervous system in the female pelvis, pelvic function, and the surgery for rectal cancer. Data such as the information provided in this study allow medical providers and their patients to make well-informed decisions about surgeries and quality of life risk factors that may guide medical management of colorectal cancer.

If you would like to feel better prepared to manage post-surgical issues that arise following treatments for colorectal cancer in women, check out the Institute’s Oncology and the Female Pelvic Floor course taught by faculty member Michelle Lyons. This continuing education course happens next in May in Torrance, California.

This post was written by Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC. You can catch Jennafer teaching the Pelvic Floor Level 2B course this weekend in Columbus.

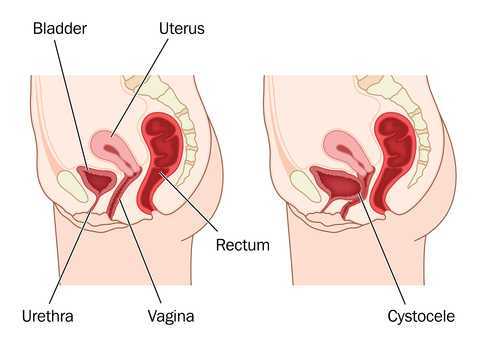

"I hate my vagina and my vagina hates me. We have a hate- hate relationship'" said my patient Sandy (name has been changed) to me after treatment. Sandy's harsh words settled between us. I understood perfectly why she might feel this way. I have been treating Sandy on and off for four years. She has had over fifteen pelvic surgeries. Her journey started with a hysterectomy and mesh implantation to treat her prolapsed bladder. She did well for several months and then her pain began. Her physician refused to believe that her pain was coming from the mesh. This pattern was repeated for several years as Sandy tried in vain to explain her pain to her medical providers. She was told her pain was all in her head and put on psych meds. Finally, five years later, Sandy found her way to an experienced urogynecologist who recognized that Sandy was having a reaction to the mesh from her prolapse surgery. It turns out that Sandy's body rejected the mesh like an allergen. Her tissues had built up fibrotic nodules to protect itself from exposure to the mesh. It has taken years and multiple operations to remove all the mesh and all the nodules. Of course then Sandy's prolapse recurred as well as her stress incontinence and she recently had surgery to try to give her some support. In PT we attempted to manage her pain, normalize her pelvic floor function, strengthen her supportive muscles and fascia. Due to years of chronic pain, her pelvic floor would spasm so completely internal work was not possible. Sandy began to also get Botox injections to her pelvic floor and pudendal nerve blocks. She uses Flexeril, Lidocaine and Valium vaginally three times a day to manage her chronic pelvic pain. She is on disability because she cannot work. Later this month Sandy will have her 16th surgery to remove a hematoma caused by her previous surgery and another nodule that we found in her left vulva. Sandy is the most complicated case of mesh complication that I have seen in my practice, however I regularly see women who have had problems with mesh that we manage through PT and also women that have had mesh removal. No one expects to have complications with their surgery and when they do it can be life altering.

In a recent review of the literature surrounding mesh complications Barski and Deng cite that over 300,000 women in the US will undergo surgical correction for stress incontinence (SUI) or pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Mesh related complications have been reported at rates of 15-25%. Mesh removal occurs at a rate of 1-2%. Mesh erosion will occur in 10% of women. There are over 30,000 cases in US courts today related to pain and disability due to mesh complications. The authors looked at mesh complication statistics from studies concerning three surgical procedures: mid urethral slings, transvaginal mesh and abdominal colposacropexy .

The authors note there are sometimes reasons why mesh goes wrong: it is used for the wrong indication, there could be faulty surgical technique, and the material properties of mesh are inherently problematic for some women. Risk factors in patient selection are previous pelvic surgery, obesity and estrogen status. There are several types of complications described: trauma of insertion, inflammation from a foreign body reaction, infection, rejection, and compromised stability of the prosthesis over time. With mid urethral slings there were also several other complications listed such as over active bladder (52%), urinary obstruction (45%), SUI (26%) mesh exposure (18%) chronic pelvic pain (18%). For transvaginal mesh, reported rate of erosion was 21%, dysparunia 11%, mesh shrinkage, abscess and fistula totaled less than 10%. Transvaginal obturator tape was noted to be traumatic for the pelvic floor. Infections that might occur in the obturator fossa require careful and through treatment. Of women who have complications 60% will end up requiring surgical removal. It is imperative to find a surgeon who is experienced and skilled with this procedure as complete excision can be difficult and there are risks of bleeding, fistula, neuropathy and recurrence of prolapse and SUI. After recovery, 10-50% of women who have had excision will have another surgery to correct POP or SUI.

As pelvic health physical therapists we are strategically poised to both help women manage SUI and POP conservatively. We also have the skills needed to help rehabilitate women dealing with complications from mesh, either to avoid removal or after removal. Our job goes beyond the physical too, often helping women cope with the emotional toll that can parallel her medical journey. At PF2B we will discuss conservative prolape management and give you tools to help patients cope with chronic pain. Would love to see you there.

In our weekly feature section, Pelvic Rehab Report is proud to present this interview with Herman & Wallace instructor Allison Ariail, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, PRPC, BCB-PMD

How did you get started in pelvic rehab?

I got started in pelvic rehab by treating and specializing in SIJ and low back dysfunction. I used ultrasound imaging to retrain the local core muscles including the transverse abdominis, lumbar multifidus, and the pelvic floor muscles. In treating these patients, not only did they improve with respects to their back pain, but their incontinence improved as well! I then started getting referrals from doctors for incontinence patients. So I took PF1 and as they say, the rest is history! I know that pelvic rehab is my calling. I am impassioned about this subject and love treating these patients. I also thoroughly enjoy teaching about the pelvic floor and the pelvic ring. I truly feel I am one of the lucky ones to actually love what I do!

What do you find most rewarding about treating this patient population?

I am passionate about treating this patient population because it makes such a difference in their lives! I have had more patients than I like to admit say that if they did not find me and get on my schedule, they would have killed themselves due to their pain. This is so sad and alarming to me that individuals have gotten to the point of considering those thoughts. I feel blessed that I am in a position to not only improve their lives in the physical sense but also in the emotional one by lessoning their pain and improving their outlook on life! To me there is nothing more rewarding than seeing this dramatic of a change in a patient.

What do you find most rewarding about teaching?

One reason I love teaching is because it is a way to help improve the lives of more people suffering with pelvic disorders! There are not enough therapists that specialize in the pelvic floor and by teaching other therapists how to appropriately treat pelvic floor dysfunction, it positively impacts more people’s lives! I always find it magical when a course participant is hesitant and nervous to take the course. Then after the course they are excited and enthusiastic to treat this patient population and to learn more about this field. This is very rewarding to me and a reason I look forward to teaching each and every course.

If you could get a message to all therapists about pelvic rehab, what would it be?

One message I would try to get out to therapists about pelvic rehab is to get out and talk about it! Discuss what you do with physicians, the community, as well as people you meet in every day life. Often, when someone finds out what you do, you will get questions asked of you. However, don’t wait for this! There are so many women and men suffering in silence thinking that there is nothing they can do. So get out there and tell them what you do and how you can help can improve lives! Don’t be hesitant or shy, be energetic and excited to share your knowledge and educate the public about what we do as pelvic therapists!

This post features an interview with Eric Dinkins, PT, MSPT, OCS, MCTA, CMP, Cert. MT, who will be instructing the brand new course, Manual Therapy for the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip Complex: Mobilization with Movement including Laser-Guided Feedback for Core Stabilization. Pelvic Rehab Report sat down with Eric to learn a little bit more about his course and his clinical approach

Can you describe the clinical/treatment approach/techniques covered in this continuing education course?

During this two day lab based course, clinicians will learn anatomy, assessment techniques, and manual therapy techniques that are designed to minimize pain and restore function immediately. As a bonus, clinicians will be introduced to stabilization exercises utilizing the Motion Guidance visual feedback system for these areas. This system allows for immediate feedback for both the clinician and the patient on determining preferred or substituted movement patterns, and enhancing motor learning to quickly address these patterns if desired.

What inspired you to create this course?

Women's and Men's health patients often have concurrent orthopedic problems that contribute to the pain or dysfunction that they are experiencing in the lumbar spine, pelvis, hips and sexual organs. There are few manual therapy courses offered that are able to bridge a gap between these two topics. This makes for a unique opportunity to offer manual therapy techniques that can address these problems and help improve clinic outcomes.

What resources and research were used when writing this course?

The books and resources I pulled from include:

Mulligan Concept of Manual Therapy 2015

Travell and Simmons Volume 2. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. The Lower Extremities

Principles of Manual Medicine 4th Edition

www.motionguidance.com

Why should a therapist take this course? How can these skill sets benefit his/ her practice?

PT's, PTA, DO's and DC's should take this course to give them knowledge and manual skills of pain free techniques to offer their Women's Health, Men's Health, and pregnancy patients with orthopedic conditions.

Among the challenges in research for chronic pelvic pain is the lack of consensus about diagnosis and intervention. Prominent researchers and physicians J. Curtis Nickel and Daniel Shoskes describe a methodology for classification of male chronic pelvic pain using phenotyping, which can be simply described as “a set of observable characteristics.” The authors point out in this article that men with complaints of pelvic pain have historically been treated with antibiotics, even though now it is known that most cases of “prostatitis” are not true infections. With most patients having chronic pelvic pain presenting with varied causes, symptoms, and responses to treatment, Nickel and Shoskes acknowledge that traditional medical approaches have not been successful.

In an attempt to improve classification of patients and subsequent treatment approaches, the UPOINT system was developed. The domains of the system include urinary, psychosocial, organ specific, infection, neurological/systemic conditions, and tenderness of skeletal muscles, and are listed below. Within each domain, the clinical description has been adapted from the original study (which can be accessed full text at the link above.)

UPOINT Domains

-Urinary: CPSI urinary score > 4, complaints of urinary urgency, frequency, or nocturia, flow rate , 15mL/s and/or obstructed pattern

-Psychosocial: Clinical depression, poor coping or maladaptive behavior such as catastrophizing, poor social interaction

-Organ specific: specific prostate tenderness, leukocytosis in prostatic fluid, haematospermia, extensive prostate calcification

-Infection: exclude patients with evidence of infection

-Neurological/systemic conditions: pain beyond abdomen and pelvis, IBS, fibromyalgia, CFS

-Tenderness of skeletal muscles: palpable tenderness and/or painful muscle spasm or trigger points in perineum or pelvic muscles

Within the initial research utilizing the UPOINT classification system, the authors report that most patients fall into more than one domain, and that the more domains a person is identified with, the more severe the symptoms. The domains leading to the highest impact are the psychosocial, neurological/systemic, and then the tenderness domain. The referenced article points out that the most impactful domains are the ones that are non-prostatocentric, or focused on dysfunction within the prostate itself. Phenotyping may indeed lead to improved classification of and treatment of male chronic pelvic pain. If you are interested in learning more about male chronic pelvic pain, there are still two opportunities to take the Male Pelvic Floor continuing education course this year. In August of this year, the course will take place in Denver, and in November, the male course will return to Seattle.

You know how some women report that they have a mild prolapse that feels better if they wear a tampon during strenuous activity, or that a tampon worn (temporarily) helps avoid urinary leakage? Using a tampon instead of a pessary seems like a great fix, with one problem: tampons are not designed to be used as a pessary. They are designed to be absorptive and to expand to fill the vaginal canal as they expand. Some women can even suffer from toxic shock syndrome - a condition related to bacterial infection and associated with super-absorbent tampon use, contraceptives, and diaphragm use. What if an item could be used that is similar to a tampon, but not absorptive, and that provided more support than a cylindrical-shaped tampon? That must have been what Kimberly Clark, the manufacturer of a new product, created to fit this need.

The Impressa is marketed as a device for urinary incontinence that a patient can buy over-the-counter. The product comes in an applicator and can be inserted similarly to the way a tampon is, but the Impressa is not made to absorb leaks. Once inserted, the product has an interesting shape that is designed to help support the urethra. The device comes in 3 sizes labeled 1, 2, and 3, and the product has a "sizing kit" with 2 of each size in a box that can be trialed for finding the best fit. It will be interesting to see how valuable this product is and we will only know as we begin to hear feedback from their use. Pessary fit is a tough process in that providers and patients often have to go through a period of trial and error for best fit, and also because providers are poorly reimbursed for management of pessary fit and use. (Click here to read more on the blog about prolapse and pessaries.)

It appears that the product is not yet widely available, but it will be interesting to hear women's' experiences about the product. Having an option for an affordable, disposable pessary-like device that is available over-the-counter could be a very helpful option to know about. Health professionals can go to the website impressapro.com to send an email requesting a sample or more information. And thank you to certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Joyce Steele for sharing information about the Impressa as this may be something your patients start asking more about. To learn more about prolapse management and female pelvic floor dysfunction, come to one of our intermediate-level continuing education courses, PF2B. The next opportunities to take this class (that aren't sold out!) are in Connecticut, North Carolina, and Missouri this year.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com/