How often have you heard that bedwetting was behavioral or caused by deep sleep and your child would outgrow it? 15% of children per year will “outgrow” bedwetting. What if your child is in the percentile at the end of that range?

Facts:

- Bedwetting affects 15% of girls and 22% of boys

- 5 - 7 Million US children

- Boys are 50% more likely than girls to wet the bed

- 10% of 6 year olds continue to wet

- Spontaneous cure rate 15% per year thereafter

- 1-3% of 18 year olds still wet their beds

- Less than 50% of all bedwetting children have bedwetting alone, without also experiencing daytime urinary leakage or constipation

- Bedwetting is genetic – if one parent was a bed wetter the child has a 40% chance of wetting the bed and if both parents were bedwetters the percentile goes up to 77%

Myths:

- Your child is lazy

- Your child is doing this to get attention

- Your child is just a deep sleeper

- You must wait to grow out of it

Research from the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) is a great resource for exploring the research on this topic and other pediatric voiding issues. www.i-c-c-s.org

What causes Bedwetting?

There are many philosophies discussed in the research. Here are some listed below:

- Hormone deficiency- our bladders empty about every 2-3 hours during the day however at night we can hold over 8 hours! This happens because our bodies produce an antidiuretic hormone when we sleep to slow kidney function and produce less urine to empty into the bladder. If this hormone is not being produced, the kidneys produce as much urine at night as they do during the day. In this case, it's good that the bladder empties out in our sleep, otherwise our bladders would be dangerously large and possibly reflux urine backward into the kidneys. Clearly not behavioral!!

- Dr. Steven Hodges has researched and written extensively on the topic of constipation causing pressure from the rectum against the bladder making it irritable during sleep. His research has supported the fact that once the bowel is cleaned out daily the bedwetting episodes diminish. See It’s No Accident by Dr. Hodges or visit https://www.bedwettingandaccidents.com for more information on this topic. Again, a physiological cause of bedwetting versus behavioral.

- Sleep Disturbance and Nasal Airway Obstruction. Dr. Neveus and colleagues reported that 43.5% of children with snoring or obstructive sleep apnea became dry after adenotonsillectomy. Dr. Kovacevic also found increases in antidiuretic hormone seen in responders post-operatively.

Take Home Message

- Active treatment for bedwetting should begin at age 6

- The impact of bedwetting is mainly psychological and may be severe

- Children with bedwetting have abnormal psychological test scores, however once the bedwetting is resolved the test scores return to normal

- “Treatment is not only justified but mandatory”

-ICCS Standardization document 2010

There is help!

At Physical Therapy Specialists we specialize in bedwetting, urinary leakage, constipation and other voiding issues in children. Let us eliminate the need for your family to suffer through this very treatable condition!

Al- Zaben FN, Sehlo MG. Punishement for bedwetting is associated with child depression and reduced quality of life. Child Abuse Negl. 2014

Hodges SJ, Colaco M. Daily enema regimen is superior to traditional therapies for nonneurogenic pediatric overactive bladder. Global Pediatric Health, 2016, 3: 1–4

Austin, P., Bauer, S.B., Bower, W., et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescence: update report from the standardization committee of the international children’s continence society. J Urol (2014) 191.

Treatment response of an outpatient training for children with enuresis in a tertiary health care setting. J Pediatr Urol. 2012.

Hodges SJ,Anthony EY::aunrecognizedof. Urology.2012 Feb;79(2):421-4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.10.015. Epub 2011 Dec 14.

Kovacevic L, Wolfe-Christensen C, Lu H, Toton M, Mirkovic J, Thottam PJ, Abdulhamid I, Madgy D, Lakshmanan Y. Why does adenotonsillectomy not correct enuresis in all children with sleep disordered breathing? J Urol. 2014 May;191(5 Suppl):1592-6.

Nevéus T, Leissner L, Rudblad S, Bazargani F. Acta Paediatr. 2014 Jul 15. doi: 10.1111/apa.12749. [Epub ahead of print]Orthodontic widening of the palate may provide a cure for selected children with therapy-resistant enuresis.

Hodges, Steve J. It’s No Accident-Breakthrough solutions for your child’s wetting, constipation, UTI’s and other potty problems. © 2012. Lyons Press, Guilford, Connecticut.

My manual therapist husband once wrote a paper on the visceral referral pattern of the liver. Although he knows I injured my right shoulder shoveling snow a few years ago, whenever I have an exacerbation of shoulder pain, he likes to joke it is from my liver. (I would laugh if I had not acquired an affinity for red wine since having kids!) Sometimes pain in remote areas of our body really can be related to an organ in distress or simply “stuck” because of fascial restrictions around it. The kidneys in particular can refer pain into the low back and hips, and the bladder and ureters can provoke saddle area pain.

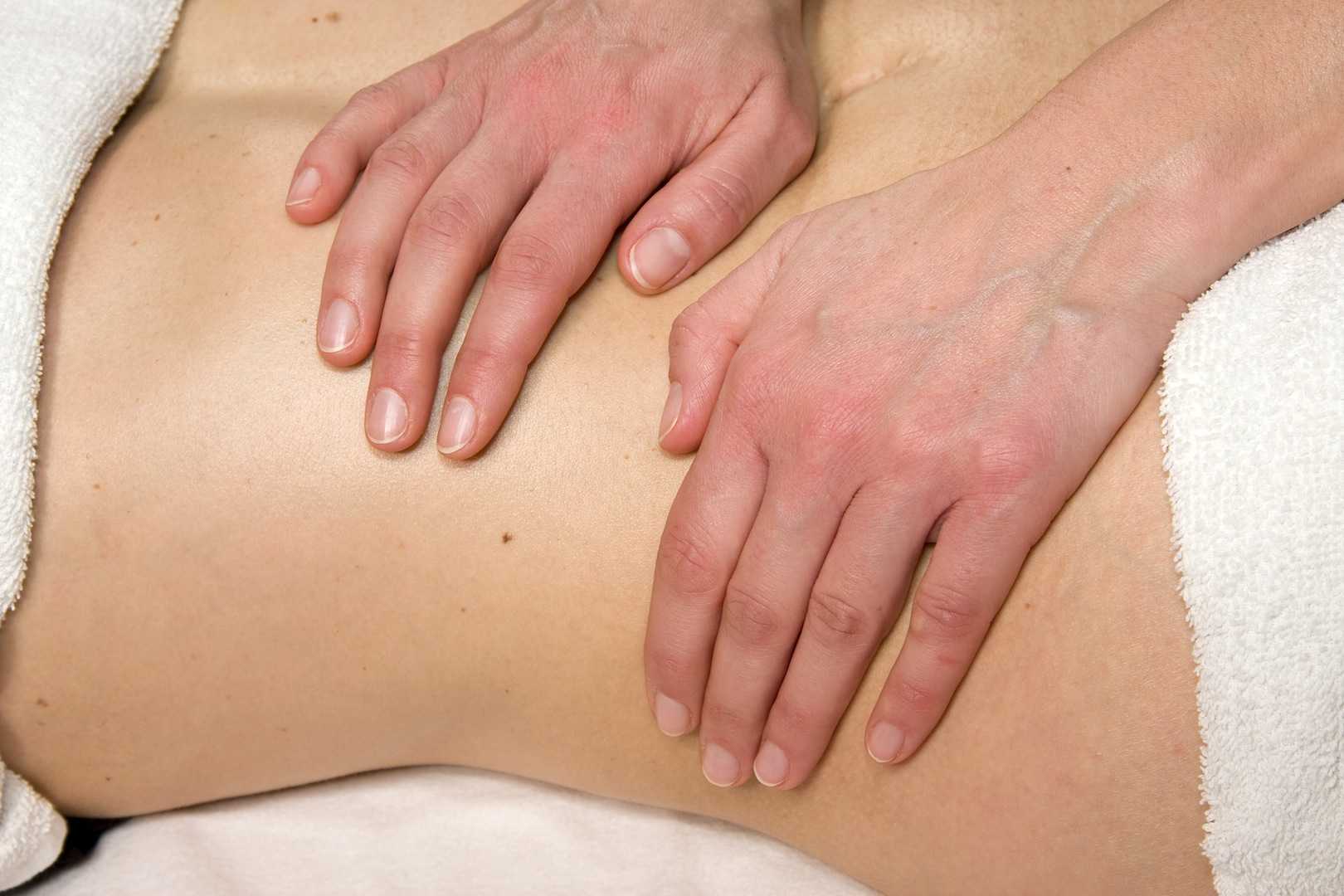

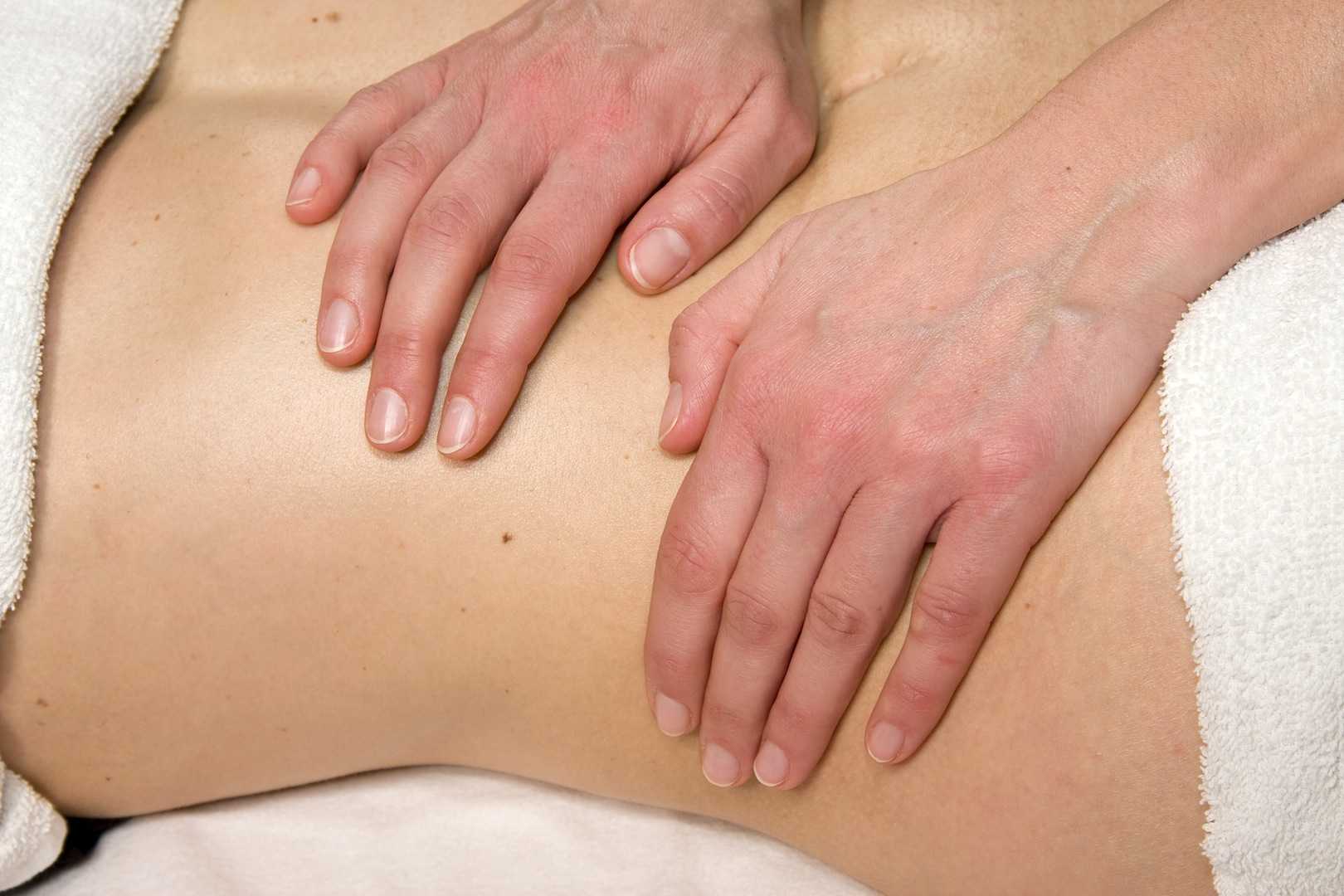

Tozzi, Bongiorno, and Vitturini (2012) looked into the kidney mobility of patients with low back pain. They used real-time Ultrasound to assess renal mobility before and after osteopathic fascial manipulation (OFM) via the Still Technique and Fascial Unwinding. The experimental group receiving OFM consisted of 109 people, and the control group receiving a sham treatment had 31 people, all with non-specific low back pain. For comparison, 101 subjects without back pain were also assessed with the ultrasound to determine a mean Kidney Mobility Score (KMS). The landmarks for measuring the renal mobility were the superior renal pole of the right kidney and the pillar of the right diaphragm, and they subtracted the distance at maximal inspiration (RdI) from that of maximal expiration (RdE). A significant difference was found in the KMS scores of asymptomatic versus symptomatic subjects with low back pain. Pre and post-RD values of the experimental group were significantly different from the control group. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire also demonstrated significant differences in the experimental versus control groups. The results of the study revealed a correlation between decreased renal mobility and non-specific low back pain and showed an improvement in renal mobility and low back pain after an osteopathic manipulation.

In 2016, Navot and Kalichman presented a case study of a 32 year old professional male cyclist with right hip and groin pain after an accident that caused a severe hip contusion and tearing of the tensor fascia latae and the gluteus medius muscles. A few rounds of physical therapy gave him partial relief of his pain in sitting and with cycling, and his hip range of motion only improved slightly. Despite no complaints of pelvic floor dysfunction, he was evaluated for involvement of the pelvic floor musculature and fascia. Pelvic Floor Fascial Mobilization was performed for 2 sessions, and the cyclist’s symptoms resolved completely. This case implied the efficacy of manual fascial release of the pelvic floor to reduce hip and groin pain.

When something seemingly orthopedic in nature does not respond with full resolution of symptoms from traditional physical therapy, the source of the pain may be deeper. Often times, we just need to ask the right questions to uncork the mystery of why a pain is lingering. No matter how skilled we are with our techniques, if we are not reaching the area in need, we are wasting our effort and our patients’ time and money. “Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System” is a course that provides a practitioner with the extra insight and tools to address potential sources of unresolved symptoms of low back, hip, and groin pain.

Tozzi, P., Bongiorno, D., and Vitturini, C. (2012) Low back pain and kidney mobility: local osteopathic fascial manipulation decreases pain perception and improves renal mobility. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 16(3):381-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.02.001

Navot, S and Kalichman, L. (2016). Hip and groin pain in a cyclist resolved after performing a pelvic floor fascial mobilization. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 20(3):604-9. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.04.005

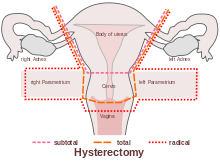

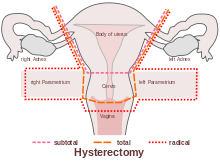

A recent systematic review by Bernard et al (2016) looked at the effects of radiation therapy on the structure and function of the pelvic floor muscles of patients with cancer in the pelvic area. Although surgery and chemotherapy are often used treatment approaches in the management of pelvic cancers, this paper specifically focused on radiation therapy: ‘… is often recommended in the treatment of pelvic cancers. Following radiation therapy, a high prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunctions (urinary incontinence, dyspareunia, and fecal incontinence) is reported. However, changes in pelvic floor muscles after radiation therapy remain unclear. The purpose of this review was to systematically document the effects of radiation therapy on the pelvic floor muscle structure and function in patients with cancer in the pelvic area.’

The paper concluded that ‘…There is some evidence that radiation therapy has detrimental impacts on both pelvic floor muscles' structure and function’ and that ‘A better understanding of muscle damage and dysfunction following radiation therapy treatment will improve pelvic floor rehabilitation and, potentially, prevention of its detrimental impacts.’

The paper concluded that ‘…There is some evidence that radiation therapy has detrimental impacts on both pelvic floor muscles' structure and function’ and that ‘A better understanding of muscle damage and dysfunction following radiation therapy treatment will improve pelvic floor rehabilitation and, potentially, prevention of its detrimental impacts.’

Pelvic floor therapists already working in the field of gynecologic oncology will be all too aware of the impacts clinically and functionally on pelvic cancer survivors’ quality of life. We are in a privileged position to provide an evidence based and solution focused approach to the pelvic health issues that are so often under-recognized, and frankly under-addressed for women undergoing treatment for pelvic cancers.

Whether it is advice on managing anal fissures (skin protection, down-training overactive pelvic floor muscles, achieving good stool consistency, teaching defecatory techniques) or dealing with dyspareunia (dilator or vibrator selection, choosing and using an appropriate lubricant, dealing with the ergonomic or orthopedic challenges that can be a barrier to returning to sexual function and enjoyment), pelvic rehab practitioners are probably the best clinicians for optimizing a return to both pelvic and global health during and after treatment for pelvic cancers.

But one of the biggest barriers we face is lack of awareness – on the part of the patients but also, unfortunately the lack of awareness in the medical and oncology community about the benefits of pelvic rehab. Happily this situation is improving – not only is the evidence base expanding from the researchers, but oncologists are recognizing that pelvic rehab is a key component of regaining quality and not just quantity of life after treatment ends. As Yang reported in his 2012 paper – pelvic floor rehab programs improve pelvic floor function (particularly urinary continence and sexual function) and overall quality of life in gynecologic cancer patients. And perhaps, most heartening of all, was his statement that "Pelvic Floor Rehab Physiotherapy is effective even in gynecologic cancer survivors who need it the most"

You can learn more about pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation for cancer patients by attending "Oncology and the Female Pelvic Floor: Female Reproductive and Gynecologic Cancers" on April 29-30, 2017 in Maywood, IL.

‘Effects of radiation therapy on the structure and function of the pelvic floor muscles of patients with cancer in the pelvic area: a systematic review.’ J Cancer Surviv. 2016 Apr;10(2):351-62. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0481-8. Epub 2015 Aug 28. Bernard, S. et al

‘Effect of a pelvic floor muscle training program on gynecologic cancer survivors with pelvic floor dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial.’ Gynecol Oncol. 2012 Jun;125(3):705-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.045. Epub 2012 Apr 1. Yang EJ, et al

When my almost 4 year old still wets his bed in the middle of the night, my first reaction is frustration; but, I learned that gets us nowhere fast, so now I just roll with the punches. Usually the culprit is my stubborn son’s simple refusal to go the bathroom before bed. When enuresis is secondary to neurogenic disorders or anxiety disorders, caregivers need to have even more patience with children.

Sturm and Cheng (2016) published a review on the management of neurogenic bladder in the pediatric population. Central nervous system (CNS) lesions including cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, and spinal malformations, as well as pelvic tumors or anorectal malformations, can all affect normal lower urinary tract function. Children with neurogenic bladder often have the condition because of a CNS lesion. This can affect the bladder’s ability to store and empty urine, so early intervention is essential and focuses on maximizing bladder function and avoiding injury to the upper or lower urinary tracts. With older children, the goals are urinary continence and independent bladder management.

Sturm and Cheng (2016) published a review on the management of neurogenic bladder in the pediatric population. Central nervous system (CNS) lesions including cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, and spinal malformations, as well as pelvic tumors or anorectal malformations, can all affect normal lower urinary tract function. Children with neurogenic bladder often have the condition because of a CNS lesion. This can affect the bladder’s ability to store and empty urine, so early intervention is essential and focuses on maximizing bladder function and avoiding injury to the upper or lower urinary tracts. With older children, the goals are urinary continence and independent bladder management.

Myelomeningocele surgical prenatal closure has had minimal effect on urinary tract function, and parents are encouraged to monitor urological changes because of the child’s risk for neurogenic bladder. Clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) has reduced the morbidity in patients with neurogenic bladder. Determining which children would benefit from initiation of CIC and when medical or surgical interventions should be implemented remains a challenge. Anticholinergics have proven effective on continence and bladder compliance either orally or, more recently, intravesical administration. Surgically, autologous augmentation using the ileum or colon has shown fatal complications like bowel obstruction and bladder rupture, particularly when bladder neck procedures are performed concurrently. Robotic versus open bladder neck reconstruction has been proving more favorable in recent studies. The authors concluded more research is needed for treatment, and the goals are preservation of the upper and lower urinary tracts, optimizing quality of life (Sturm and Cheng 2016).

Considering a different side of nerves, Salehi et al., (2016) studied the relationship between primary nocturnal enuresis and child anxiety disorders. They studied 180 children with primary nocturnal enuresis (referring to children >5 years old having no urine control 6 continuous months) and 180 healthy controls. A statistically significant difference was found between the two groups regarding the frequency of generalized anxiety disorder as well as panic disorder, school phobia, social and separation anxieties, maternal anxiety history, parental history of primary nocturnal enuresis and body mass index. The authors recommended any children with primary nocturnal enuresis should be assessed and treated for generalized anxiety disorder.

The seriousness of enuresis cannot be underestimated. When the cause is neurogenic, pharmacological or surgical intervention may be warranted and lifelong urologic management is needed, especially for a healthy transition into adulthood. As common as nocturnal bed wetting may be in school aged children, they should be monitored for the presence of any anxiety disorders that may be contributing to the disorder. Changing sheets may feel like a burden for parents, but the child with enuresis has a far greater weight to bear.

You can learn all about caring for pediatric patients by attending Pediatric Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction with Dawn Sandalcidi, available twice in 2017.

Sturm, R. M., & Cheng, E. Y. (2016). The Management of the Pediatric Neurogenic Bladder. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports, 11, 225–233. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11884-016-0371-6

Salehi, B., Yousefichaijan, P., Rafeei, M., & Mostajeran, M. (2016). The Relationship Between Child Anxiety Related Disorders and Primary Nocturnal Enuresis. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 10(2), e4462. http://doi.org/10.17795/ijpbs-4462

In this “quick fix” society, few people accept that musculoskeletal pain will require a commitment to following an exercise program for an extended period of time. If a hypomobile joint just needs to get moving and lubricated, one may get relief with a few manual therapy treatments and exercise sessions. However, if a joint is hypermobile (unstable) or degenerative and provokes a high level of pain, the rehab requires more time. The sacroiliac (SI) joint is one of those areas often requiring patients to work harder for the resolution of pain and dysfunction, but many seek surgical intervention instead.

Polly et al. (2016) performed a randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion (SIJF) with placement of a system of triangular titanium implants using a lateral transiliac approach versus non-surgical management (NSM) for SI dysfunction. Of the 148 subjects, 102 underwent SIJF and 46 had NSM. The NSM group received medication, physical therapy per American Physical Therapy Association guidelines, steroid injections and radiofrequency ablation of sacral nerve root lateral branches. The surgical group showed superior outcomes at a 2 year follow up, as clinical improvement per VAS pain score was 83.1% and ODI was 68.2%. The NSM group showed <10% improvement.

Polly et al. (2016) performed a randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion (SIJF) with placement of a system of triangular titanium implants using a lateral transiliac approach versus non-surgical management (NSM) for SI dysfunction. Of the 148 subjects, 102 underwent SIJF and 46 had NSM. The NSM group received medication, physical therapy per American Physical Therapy Association guidelines, steroid injections and radiofrequency ablation of sacral nerve root lateral branches. The surgical group showed superior outcomes at a 2 year follow up, as clinical improvement per VAS pain score was 83.1% and ODI was 68.2%. The NSM group showed <10% improvement.

Sachs et al. (2016) studied outcomes of patients ≥3 years after SIJF for chronic (>5 years) SIJ dysfunction secondary to degenerative sacroiliitis or SIJ disruption. One hundred and seven patients participated in the study, and minimally invasive transiliac SIJF was definitively correlated with decreased pain, low disability scores, and improvements in activities of daily living performance. Sadly, these authors stated, “there is no high-quality evidence that physical therapy is effective in chronic SIJ pain.”

Even radiofrequency neurotomy or neural ablation revealed positive results for patients according to Reddy et al. (2016). The authors explored 14 patients’ responses 1 year after Simplicity radiofrequency (RF) of the lateral branches of S1-S3 in a retrospective review. Improvements in global health per SF12 as well as pain reduction were statistically significant.

Jonely et al. (2015) presented a case study of a woman with a 14-year history of SIJ pain whose symptoms persisted after 2 months of physical therapy. A multi-modal approach was then pursued with success, even at the 1 year follow up. The patient received 4 prolotherapy injections, SIJ manipulation into nutation, a pelvic girdle belt, and specific stabilization exercises. Over a 12-month period, the patient had 20 physical therapy sessions. Her Oswestry Disability score improved from 34% to 14% at 6 months and was 0% at 1 year. Numeric pain scale rating improved to 4/10 at 6 months and 0/10 at 1 year. The authors concluded a multimodal approach can be successful to manage SIJ dysfunction.

Clearly, if quality of life is so poor a person cannot function because of SIJ pain and therapy has failed, surgery may be the only choice. I exhaust all conservative measures before I cry “uncle” for a surgical fix. Despite a paucity of literature on manual therapy and sacroiliac treatment, I know there are clinicians successfully treating patients with SI dysfunction. Taking the Sacroiliac Joint Evaluation and Treatment can broaden your scope of understanding the SI joint and how to provide the most effective treatment, possibly preventing more invasive techniques for patients.

Polly, D. W., Swofford, J., Whang, P. G., Frank, C. J., Glaser, J. A., Limoni, R. P., … and the INSITE Study Group. (2016). Two-Year Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial of Minimally Invasive Sacroiliac Joint Fusion vs. Non-Surgical Management for Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction. International Journal of Spine Surgery, 10, 28. http://doi.org/10.14444/3028

Sachs, D., Kovalsky, D., Redmond, A., Limoni, R., Meyer, S. C., Harvey, C., & Kondrashov, D. (2016). Durable intermediate-to long-term outcomes after minimally invasive transiliac sacroiliac joint fusion using triangular titanium implants. Medical Devices (Auckland, N.Z.), 9, 213–222. http://doi.org/10.2147/MDER.S109276

Anjana Reddy, V. S., Sharma, C., Chang, K.-Y., & Mehta, V. (2016). “Simplicity” radiofrequency neurotomy of sacroiliac joint: a real life 1-year follow-up UK data. British Journal of Pain, 10(2), 90–99. http://doi.org/10.1177/2049463715627287

Jonely, H., Brismée, J.-M., Desai, M. J., & Reoli, R. (2015). Chronic sacroiliac joint and pelvic girdle dysfunction in a 35-year-old nulliparous woman successfully managed with multimodal and multidisciplinary approach. The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 23(1), 20–26. http://doi.org/10.1179/2042618614Y.0000000086

After greeting a patient referred for temporomandibular joint dysfunction, the conversation began with an outpouring of emotion over a failed bladder sling surgery that left the woman with significant chronic pain, causing her to clench her jaw all the time. No matter what I was to find objectively with the examination, there was no doubt the treatment had to extend beyond joint mobilization, soft tissue work, and exercise. This woman clearly saw her cup as half empty, so filling her mind with a new approach to thinking about and dealing with her pain was essential for relieving her secondary jaw pain.

Su et al. published a study called, “Pain Perception Can Be Modulated by Mindfulness Training: A Resting-State fMRI Study” (2016). The pain-afflicted group had 18 participants while the control group had 16. Brain behavior response of all subjects was measured per resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging and 3 forms (Dallas Pain Questionnaire, Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire-SFMPQ, and Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness) before and after 6 weeks of mindfulness-based stress reduction treatment. Training consisted of mindfulness meditations such as a body scan, hatha yoga, walking and sitting meditation, and instruction on how to use the methods for pain management. After six 2.5-hour sessions/week and one 8-hour non-verbal session in the 4th week, the fMRI showed an increased connection from the anterior insular cortex (AIC) to the dorsal anterior midcingulate cortex (daMCC), and the SFMPQ scores were significantly improved in the pain-afflicted group. The authors suggested mindfulness training can change the brain connectivity responsible for our perception of pain.

Su et al. published a study called, “Pain Perception Can Be Modulated by Mindfulness Training: A Resting-State fMRI Study” (2016). The pain-afflicted group had 18 participants while the control group had 16. Brain behavior response of all subjects was measured per resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging and 3 forms (Dallas Pain Questionnaire, Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire-SFMPQ, and Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness) before and after 6 weeks of mindfulness-based stress reduction treatment. Training consisted of mindfulness meditations such as a body scan, hatha yoga, walking and sitting meditation, and instruction on how to use the methods for pain management. After six 2.5-hour sessions/week and one 8-hour non-verbal session in the 4th week, the fMRI showed an increased connection from the anterior insular cortex (AIC) to the dorsal anterior midcingulate cortex (daMCC), and the SFMPQ scores were significantly improved in the pain-afflicted group. The authors suggested mindfulness training can change the brain connectivity responsible for our perception of pain.

Chadi et al.2016 performed a pilot study of female adolescents with chronic pain regarding the efficacy of mindfulness-based treatment. The experimental group (n=10) and the wait-list control group (n=9) consisted of girls between the ages of 13 and 18. For 8 weeks they met for a 90 minute session led by a psychiatry resident. Some of the mindfulness practices in this study included body scan, sitting and walking meditations, love and kindness meditations, mindful eating, compassion and deep listening, and breathing exercises. The wait-list control group also completed the 8-week program. Although all participants reported a positive change in the way they coped with pain, no statistically significant changes in quality of life, depression, anxiety, pain perception, and psychological distress were found. Significant salivary cortisol level improvements were observed (p<0.001) post mindful-based treatment session, indicating feasibility in pursuing further research with a larger randomized controlled trial.

Panahi and Faramarzi2016 studied mindfulness therapy effects on anxiety and depression for premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Sixty students (30 experimental, 30 control with no treatment) with mild to moderate PMS with depression underwent 8 weekly 120 minute sessions of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). Mean score improvements in depression, anxiety, and PMS were statistically significant from pre to post treatment for the subjects receiving MBCT. The authors stated MBCT psychotherapy could be considered beneficial for depression in mild to moderate PMS.

If jaw-clenching chronic pain owns a patient, he or she could benefit from managing the relationship through mindfulness. Our perception of pain is at the core of “whole body” treatment. The Mindfulness Based Pain Treatment course could help fill your patients’ as well as your own cup with healing.

If you're interested in learning more about mindfulness-based treatment techniques, Herman & Wallace offers three courses which you should consider. Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment focuses on patient treatment, and the Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals.

Su, I.-W., Wu, F.-W., Liang, K.-C., Cheng, K.-Y., Hsieh, S.-T., Sun, W.-Z., & Chou, T.-L. (2016). Pain Perception Can Be Modulated by Mindfulness Training: A Resting-State fMRI Study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 570. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00570

Chadi, N., McMahon, A., Vadnais, M., Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Djemli, A., Dobkin, P. L., … Haley, N. (2016). Mindfulness-based Intervention for Female Adolescents with Chronic Pain: A Pilot Randomized Trial. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(3), 159–168.

Panahi, F., & Faramarzi, M. (2016). The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy on Depression and Anxiety in Women with Premenstrual Syndrome. Depression Research and Treatment, 2016, 9816481. http://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9816481

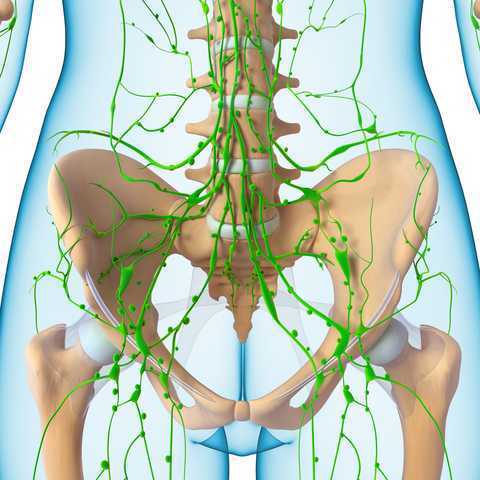

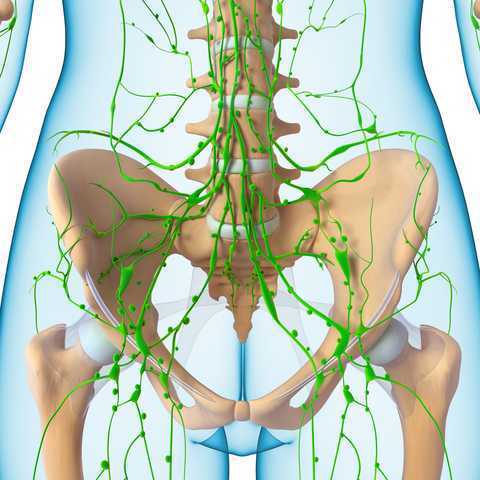

In 1998, faculty member Debora Chassé was asked to evaluate a patient with bilateral lower extremity lymphedema following repeated surgeries for cervical cancer. Her formal education did not cover this in school, so Dr. Chassé began to study peer-review research and consult with other clinicians about the diagnosis. Her journey down the rabbit hole began.

In 1998, faculty member Debora Chassé was asked to evaluate a patient with bilateral lower extremity lymphedema following repeated surgeries for cervical cancer. Her formal education did not cover this in school, so Dr. Chassé began to study peer-review research and consult with other clinicians about the diagnosis. Her journey down the rabbit hole began.

Dr. Chassé became a certified lymphedema therapist in 2000 and a certified Lymphology Association of North America therapist in 2001. She continued training by moving into osteopathy taking her into the direction of lymphatic vessel manipulation. In 2006 she began taking courses in pelvic pain and obstetrics with a focus on pelvic floor dysfunction. It was at this point that Dr. Chasse realized nobody was applying lymphatic treatment to women’s health and pelvic floor dysfunction. In 2009 she became a Board Certified Women’s Health Clinical Specialist in Physical Therapy and began traveling around the United States offering workshops in the area of lymphatic treatment.

Dr. Chassé’s approach is to incorporate all her varied skills in the clinic to produce the best patient outcomes. Debora explains that she is “…showing the similarities between pelvic pain and the lymphatic system. The treatment principles are the same, when you are treating both lymphedema or pelvic pain, you are working to reduce inflammation, pain and scarring.”

Another advantage of the lymphatic treatment approach is that it is more comfortable for the patient. “Most intravaginal techniques causes increased pain and inflammation. However, using lymphatic drainage intravaginally is well tolerated and decreases the intravaginal pain. The results are phenomenal!”

Dr. Chassé recollects her experience with a 21 year old female who suffered from chronic pelvic pain. By applying intravaginal lymphatic drainage techniques for 5 consecutive days, the patient experience a 4.83 reduction in pelvic girdle circumference and her intravaginal pain went from 8/10 to 2/10. The patient was amazed at how much better she felt. “My pants fit better, my energy level increased 25% and pain decreased more than 50%. I went from having 2-3 bad days per week to having 2-3 bad days per month, even when my work level increased. My feet no longer swell and I haven’t missed any classes since receiving this treatment.

In her course, “Lymphatics and Pelvic Pain: New Strategies”, Dr. Chassé seeks to train practitioners to utilize lymphatic drainage techniques when treating specifically pelvic pain. Participants will learn lymphatic drainage principles and techniques. They will learn how to clear pathways to transport lymph fluid and internal techniques which will have incredible impacts for patients.

Honestly, I have never noticed Curcumin on any of my patients’ lists of pharmaceuticals or supplements, but I will be certain to look for it now. Curcumin is the fat-soluble molecule that gives turmeric its yellow pigment, and it is best absorbed with the addition of black pepper extract. Patients often complain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (NSAIDs) tear apart their stomachs, so newer studies showing positive results with the use of an herb sound promising, even for pelvic health.

A 2015 study by Kim et al. researched the inhibitory effect of curcumin on benign prostatic hyperplasia induced by testosterone in a rat model. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is common among men and has a negative impact on the urinary tract of older males. Steroid 5-alpha reductase converts testosterone into dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and this increases as men age and may have negative effects on the prostate gland. Because of the side effects of conventional drugs (like finasteride) to inhibit steroid 5-alpha reductase, the authors wanted to determine if curcumin could play a protective role in BPH. They divided 8 rats into 4 groups after removal of testicles: 1) normal, 2) BPH testosterone induced subcutaneously, 3) daily curcumin (50mg/kg orally), and 4) daily finasteride (1mg/kg orally). The group receiving curcumin had significantly lower prostate weight and volume than the testosterone induced BPH group, and curcumin decreased the expression of growth factors in prostate tissue. The authors conclude curcumin may be a useful herb in inhibiting the development of BPH with fewer side effects than conventional drugs.

A 2015 study by Kim et al. researched the inhibitory effect of curcumin on benign prostatic hyperplasia induced by testosterone in a rat model. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is common among men and has a negative impact on the urinary tract of older males. Steroid 5-alpha reductase converts testosterone into dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and this increases as men age and may have negative effects on the prostate gland. Because of the side effects of conventional drugs (like finasteride) to inhibit steroid 5-alpha reductase, the authors wanted to determine if curcumin could play a protective role in BPH. They divided 8 rats into 4 groups after removal of testicles: 1) normal, 2) BPH testosterone induced subcutaneously, 3) daily curcumin (50mg/kg orally), and 4) daily finasteride (1mg/kg orally). The group receiving curcumin had significantly lower prostate weight and volume than the testosterone induced BPH group, and curcumin decreased the expression of growth factors in prostate tissue. The authors conclude curcumin may be a useful herb in inhibiting the development of BPH with fewer side effects than conventional drugs.

In the urology realm, Cosentino et al.2016 explored the anti-inflammatory effects of a product called Killox®, a supplement with curcumin, resveratrol, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and zinc. When benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is not treated with drugs, a surgical intervention can be executed called a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP); or, for bladder cancers, a transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB) can be performed. Either surgery generally requires administration of NSAIDs post-operatively for inflammation, urinary burning, or bladder spasms or to prevent later complications such as urethral stricture or sclerosis of the bladder neck. This open controlled trial involved Killox® tablet administration to 40 TURP patients twice a day for 20 days, to 10 TURB patients twice a day for 10 days and to 30 BPH patients who were not suited for surgical intervention once a day for 60 days. The control group received nothing for 1 week post-surgery, and 52.5% of TURP and 40% of TURB patients required NSAIDs to treat burning and inflammation the following 7 days. None of the Killox® treatment groups had post-operative or late complications except one, and none suffered epigastric pain like those using NSAIDs. The authors concluded Killox® had significant positive anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects on the patients and could be used as a safe alternative to NSAIDs by physicians.

Although “just” an herb, the use of curcumin should be supervised by a healthcare professional who understands proper dosage and any possible contraindications for a particular individual. The curcumin needs to be in a form that can be easily digested and used effectively by the body. Ultimately, it is exciting to learn about an alternative to gut-wrenching NSAIDs, making curcumin a noteworthy anti-inflammatory option for patients.

Nutrition plays an important part in patient wellness and rehabilitation. There are many reasons to consider diet when designing treatment regimens and you can learn all about them in Megan Pribyl's Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist course. Your next chance to take this course is March 31 - April 1, 2017 in White Plains, NY. Don't miss out!

Kim, S. K., Seok, H., Park, H. J., Jeon, H. S., Kang, S. W., Lee, B.-C., … Chung, J.-H. (2015). Inhibitory effect of curcumin on testosterone induced benign prostatic hyperplasia rat model. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine,15, 380. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-015-0825-y

Cosentino, V., Fratter, A., Cosentino M. (2016). Anti-inflammatory effects exerted by Killox®, an innovative formulation of food supplement with curcumin, in urology. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 20: 7, 1390-1398. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27097964#

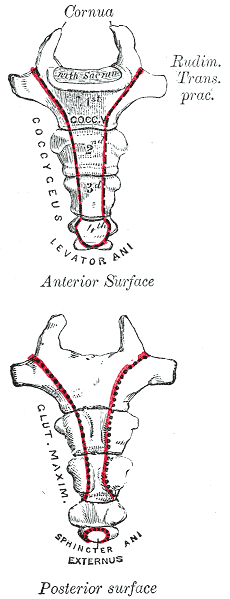

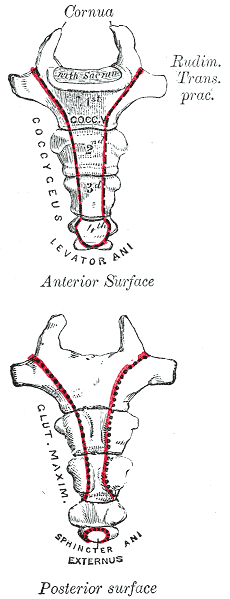

In my mid 20’s I had a sudden onset of severe, persistent pain at the bottom of my spine. I had fallen while running on trails and thought maybe I had fractured my coccyx. It hurt terribly to sit, especially on hard surfaces. When I finally succumbed to seeing a doctor, he diagnosed me with a pilonidal cyst and performed a simple excision of the infection right there in the office. I recall passing out on the table and waking up with an open wound stuffed with gauze. What I thought was “just” coccydynia turned out to be something completely different, requiring a specific and immediately effective treatment.

Differential diagnosis is essential in all medical professions. Blocker, Hill, and Woodacre2011 presented a case report on persistent coccydynia and the necessity of differential diagnosis. A 59-year old female reported constant coccyx pain after falling at a wedding. Her initial x-rays were normal, as was an MRI a year later, despite continued pain. Neither an ultrasound nor abdominal CT scan was performed until 16 months after the onset of pain, which was 2 months after she started having bladder symptoms. A CT scan then showed a tumor stemming from her sacrum and coccyx, and an MRI confirmed the sacrum as the tumor location. Chordomas are primary bone tumors generally found at the sacrum and coccyx or the base of the skull. They are relatively rare; however, they do exist in males and females and can present as low back pain, a soft tissue mass, or bladder/bowel obstruction. Clinicians need to listen for red flags of night pain and severe, unrelenting pain and ensure proper examination is performed for accurate diagnosis and expedient treatment.

Differential diagnosis is essential in all medical professions. Blocker, Hill, and Woodacre2011 presented a case report on persistent coccydynia and the necessity of differential diagnosis. A 59-year old female reported constant coccyx pain after falling at a wedding. Her initial x-rays were normal, as was an MRI a year later, despite continued pain. Neither an ultrasound nor abdominal CT scan was performed until 16 months after the onset of pain, which was 2 months after she started having bladder symptoms. A CT scan then showed a tumor stemming from her sacrum and coccyx, and an MRI confirmed the sacrum as the tumor location. Chordomas are primary bone tumors generally found at the sacrum and coccyx or the base of the skull. They are relatively rare; however, they do exist in males and females and can present as low back pain, a soft tissue mass, or bladder/bowel obstruction. Clinicians need to listen for red flags of night pain and severe, unrelenting pain and ensure proper examination is performed for accurate diagnosis and expedient treatment.

In a more recent case study by Gavriilidid & Kyriakou 2013, a 73 year old male presented with 6 months of tailbone pain, worse with sitting and rising from sitting. The physician initially referred him to a surgeon for a pilonidal cyst he diagnosed upon palpation. The surgeon found an unusual mass and performed a biopsy, which turned out to be a sacrococcygeal chordoma. The tumor was excised surgically along with the gluteal musculature, coccyx, and the fifth sacral vertebra, as well as a 2cm border of healthy tissue to minimize risk of recurrence of the chordoma. These authors reported coccygodynia is most often caused by pilonidal disease, clinically confirmed by abscess/sinus, fluid drainage, and midline skin pits. They concluded from this case study if one or more of those characteristic findings are absent, differential diagnoses of chordoma, perineural cyst, giant cell tumour, intra-osseous lipoma, or intradural Schwannoma should be investigated.

Honestly, if I were not a physical therapy tech when my coccyx started killing me 20 years ago, I am not sure I would have gone to the doctor right away. My boss called me out when I winced every time I sat down, and he sent me off to get an exam. The majority of patients are not blurting out specific details about buttock pain when they come for evaluation. Modesty prevails but does not always benefit a patient with persistent coccydynia. Thankfully I did not have a chordoma, but the pain was intense enough to bring me to tears, and it could have required surgery if I had not been diagnosed early enough. Providing a comfortable environment for our patients during their initial encounter can help them feel less vulnerable and discuss the root of their pain. If we can decipher between chordoma and other causes of coccydynia, we may strike a chord that saves a patient from a poor outcome.

The Herman & Wallace course "Coccyx Pain Evaluation & Treatment" is an excellent opportunity to learn new differential diagnosis techniques for coccyx pain patients. The next opportunity to attend this course is March 25-26 in Tampa, Florida.

Blocker, O., Hill, S., & Woodacre, T. (2011). Persistent coccydynia – the importance of a differential diagnosis. BMJ Case Reports, 2011, bcr0620114408. http://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.06.2011.4408

Gavriilidis, P., & Kyriakou, D. (2013). Sacrococcygeal chordoma, a rare cause of coccygodynia. The American Journal of Case Reports, 14, 548–550. http://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.889688

In the world of pelvic health, we are constantly meeting patients who are surprised to learn about the scope of what we do. Oftentimes, it is because we mention the pelvic muscles’ roles in sexual health that a patient will offer up symptoms with their sexual health, or ask a few more questions. Outside of pelvic health professionals asking about sexual function, do men bring up these issues with anyone? Not usually. In Fisher and colleagues 2-part “Strike up a conversation” study (2005), the authors reported that men who have erectile dysfunction (ED) are worried about their partner’s reaction, don’t want to admit to having a chronic problem, and frankly, just don’t even know where to start. Unfortunately, the partners of men who have ED have the same concerns. In addition, partners are worried about bringing it up and “making their partners feel worse about it.” When men did bring up sexual concerns with their physician, although they reported feeling nervous and embarrassed, they also reported feeling hopeful and relieved.

This issue was highlighted in a recent interview and article published on National Public Radio. The article shares that for war veterans, sexual intimacy is often affected, and yet, is often ignored. A Marine who suffered PTSD after a head injury and shrapnel to the head and neck describes how he had to go to the doctor several times just to work up the nerve to ask for help for his sexual dysfunction. He also shared how it was difficult to talk about “…because it contradicts a self-image so many Marines have.” Apparently you don’t have to be a Marine to feel the same intense pressure related to talking about sexual issues. I have spent more time in the past year trying to better understand why men don’t discuss these issues, with a best friend or partner, and each time, my question of “what would that be like if you brought it up?” is met with near bewilderment, as if revealing this issue were akin to revealing your deepest, darkest secret. Apparently, it is. Telling a buddy you have erectile dysfunction, for men, seems to be like showing your enemy where the chink in your armor is, or like setting yourself up to be the center of every “getting it up” joke for the remainder of your life.

This issue was highlighted in a recent interview and article published on National Public Radio. The article shares that for war veterans, sexual intimacy is often affected, and yet, is often ignored. A Marine who suffered PTSD after a head injury and shrapnel to the head and neck describes how he had to go to the doctor several times just to work up the nerve to ask for help for his sexual dysfunction. He also shared how it was difficult to talk about “…because it contradicts a self-image so many Marines have.” Apparently you don’t have to be a Marine to feel the same intense pressure related to talking about sexual issues. I have spent more time in the past year trying to better understand why men don’t discuss these issues, with a best friend or partner, and each time, my question of “what would that be like if you brought it up?” is met with near bewilderment, as if revealing this issue were akin to revealing your deepest, darkest secret. Apparently, it is. Telling a buddy you have erectile dysfunction, for men, seems to be like showing your enemy where the chink in your armor is, or like setting yourself up to be the center of every “getting it up” joke for the remainder of your life.

The bottom line is that we can be part of the solution to this problem, because men must be certain that their medical provider knows about any emerging or worsening erectile dysfunction. Loss of libido, or changes in erectile function can be associated with heart issues, with diabetes, or with other major medical concerns. Research such as the referenced “strike up a conversation study” has demonstrated that health care providers or partners may positively influence a patient’s access to care. Once medical evaluation has been completed, the role of the pelvic health provider is critical in improving sexual health for men with dysfunction. If you are interested in learning more about the role of the pelvic health provider for erectile dysfunction or pain related to sexual function, the Male Pelvic Health continuing education course will be offered 3 times this year through the Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute. Your next opportunity to learn about urinary and prostate conditions, male pelvic pain, sexual health and dysfunction is next month in Portland, Oregon.

Chang, A. (2016). For veterans, trauma of war can persist in struggles with sexual intimacy. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/01/01/507749611/for-veterans-trauma-of-war-can-persist-in-struggles-with-sexual-intimacy

Fisher, W. A., Meryn, S., Sand, M., Brandenburg, U., Buvat, J., Mendive, J., ... & Strike Up a Conversation Study Team. (2005). Communication about erectile dysfunction among men with ED, partners of men with ED, and physicians: The Strike Up a Conversation Study (Part I). The journal of men's health & gender, 2(1), 64-78.

Fisher, W. A., Meryn, S., Sand, M., & Strike up a Conversation Study Team. (2005). Communication about erectile dysfunction among men with ED, partners of men with ED, and physicians: the Strike Up a Conversation study (Part II). The journal of men's health & gender, 2(3), 309-e1.