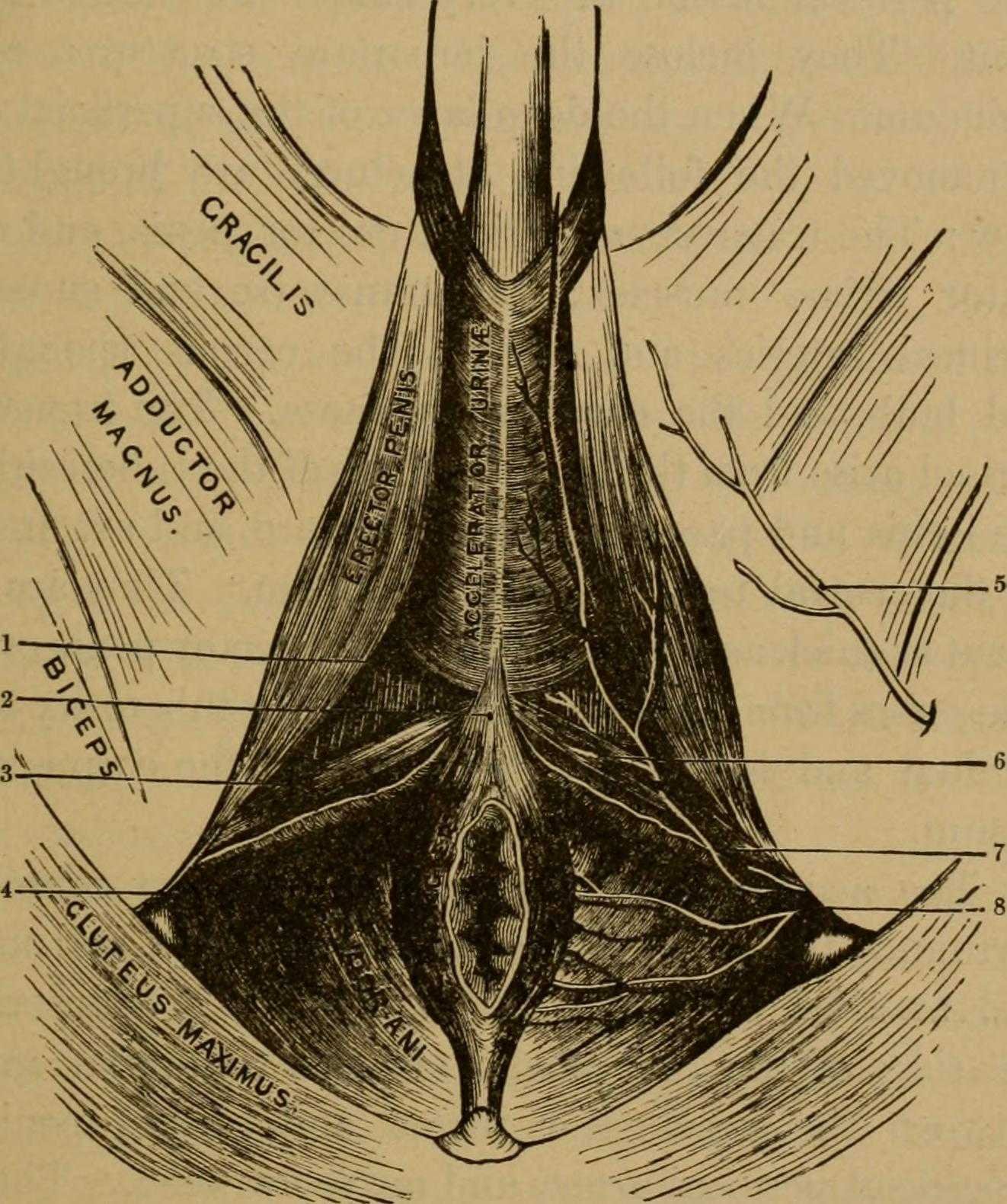

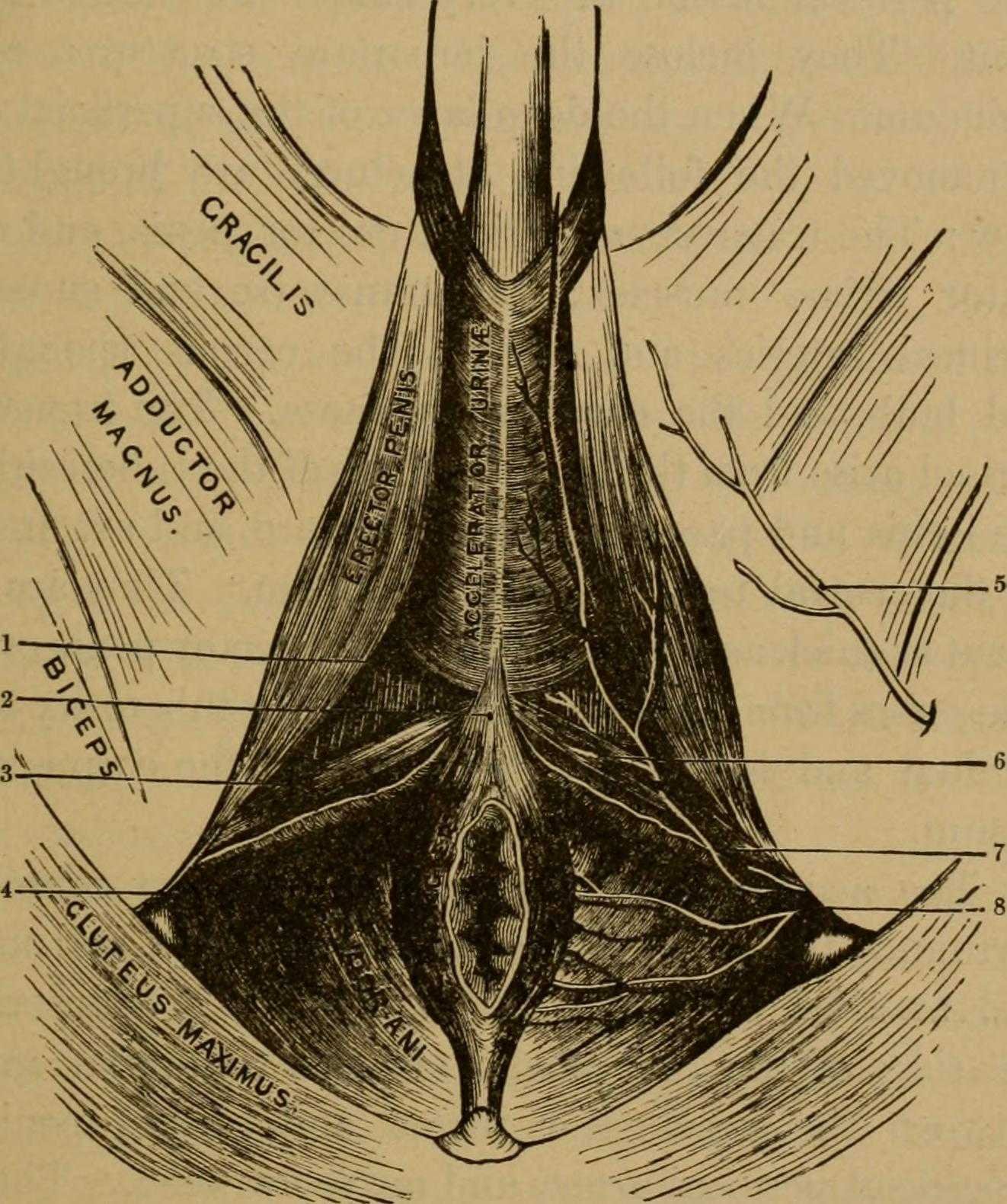

Many therapists transition to treating men with the knowledge and training from female patients. When therapists apply this knowledge, for the most part, it works. When we spend some attention on learning what is a bit different, we might be drawn to the superficial muscles of the perineum. This old anatomy image does a wonderful job of "calling it like it is" or using anatomical terms that describe an action versus naming only the structure. In the image we are looking from below (inferior view) at the perineum and genitals. Just anterior to the anus we can see the anterior muscles within the urogenital triangle, with the base of the shaft of the penis located just anterior to (above in this image) the anus and perineal body. Notice that at the midline, we see muscle names the "accelerator urine". Modern textbooks refer to this muscle as the bulbocavernosus, or bulbospongiosus. Taking the name of accelerator urine, we can understand that this muscle will have an effect on aiding the body in emptying urine. It does this through rhythmic contractions, most often noted towards the end of urination, when the typical spurts of urine follow a more steady stream. This assistance with emptying can take place because the urethra is located within the lower part of the penis, the portion known as the corpus spongiosum. Because the bulbocavernosus muscle covers this part of the penis, and the inferior and lateral parts of the urethra are virtually wrapped within the bulbocavernosus, the muscle can have an effect on emptying the urine in the urethra.

Many therapists transition to treating men with the knowledge and training from female patients. When therapists apply this knowledge, for the most part, it works. When we spend some attention on learning what is a bit different, we might be drawn to the superficial muscles of the perineum. This old anatomy image does a wonderful job of "calling it like it is" or using anatomical terms that describe an action versus naming only the structure. In the image we are looking from below (inferior view) at the perineum and genitals. Just anterior to the anus we can see the anterior muscles within the urogenital triangle, with the base of the shaft of the penis located just anterior to (above in this image) the anus and perineal body. Notice that at the midline, we see muscle names the "accelerator urine". Modern textbooks refer to this muscle as the bulbocavernosus, or bulbospongiosus. Taking the name of accelerator urine, we can understand that this muscle will have an effect on aiding the body in emptying urine. It does this through rhythmic contractions, most often noted towards the end of urination, when the typical spurts of urine follow a more steady stream. This assistance with emptying can take place because the urethra is located within the lower part of the penis, the portion known as the corpus spongiosum. Because the bulbocavernosus muscle covers this part of the penis, and the inferior and lateral parts of the urethra are virtually wrapped within the bulbocavernosus, the muscle can have an effect on emptying the urine in the urethra.

Notice that if you follow the fibers of the accelerator urine muscle towards the top of the image, where the penis continues, you will notice fibers of the muscle wrapping around the sides of the penis. These fibers will continue as a fascial band that travels over the dorsal vessels of the penis. This allows the muscle to also have a significant action during sexual activity, in which blood flow (getting blood into, keeping blood in, and letting blood out of the penis) is paramount.

On either side of the penis we can see what is labeled the erector penis. As these muscles cover the legs, or crura which form the two upper parts of the penis, when the muscles contract, blood is shunted towards the main body of the penis. This of course helps with penile rigidity, as the smooth muscles in the artery walls of the penis allow blood to fill the spongy chambers.

Once we discuss the usual functions of these muscles, we can then imagine the dysfunctions potentially created by less than optimal activity. Consider the difficulty that these muscles will create in contracting or relaxing if they are either too weak, or too tense. These issues can create difficulty emptying well the urethra, often leading to post-void dribble. Blood flow and therefore penile rigidity with erections may be negatively impacted by inability of these muscles to contract or stay contracted, and blood flow leaving the penis may be impaired if the muscles cannot relax. When we work with patients who have genital pain, pelvic floor muscle weakness, dyscoordination, or tension, we can often improve sexual function, bladder emptying, and tasks that might otherwise be affected by pain.

If you are interested in learning more about how to assess and treat these muscles, you have one more opportunity this year to attend the 3-day Male Course instructed by Holly Tanner. Holly has been teaching this course for over 10 years when she co-wrote the first course with colleague and faculty member Stacey Futterman. The course has been updated and turned into a 3-day course to include more manual therapy techniques. Hurry to grab one of the remaining spots in the October 27-29 course in Grand Rapids!

At the peak of my racing career I won awards in all my races from 5k to marathon. While warming up I would scope out my competition, intimidated by muscular females wearing outfits to accentuate their physiques. Many times, appearance out-weighed running capacity. In a similar manner, one strong pelvic floor contraction produced by a female athlete does not always mean she has the endurance to stay dry in the long run.

Brennand et al. (2017) researched urinary leakage during exercise in Canadian women. A summary of their findings concluded that skipping, trampoline, jumping jacks, and running/jogging were most likely to cause leakage. To combat the problem, 93.2% emptied their bladder just before exercise, 62.7% required voiding breaks during exercise, and 37.3% actually restricted their fluid intake to minimize leakage. While 90.3% of women who reported leakage impacted their activity just decreased their intensity, 80.7% avoided the activity entirely. Many women used pads (49.2%). Interest in pelvic floor physiotherapy to improve their UI was high (84.6%), but 63.5% of women still sought pessary or surgical management. Unfortunately, 35.6% of the women had no idea treatment was even an option.

Brennand et al. (2017) researched urinary leakage during exercise in Canadian women. A summary of their findings concluded that skipping, trampoline, jumping jacks, and running/jogging were most likely to cause leakage. To combat the problem, 93.2% emptied their bladder just before exercise, 62.7% required voiding breaks during exercise, and 37.3% actually restricted their fluid intake to minimize leakage. While 90.3% of women who reported leakage impacted their activity just decreased their intensity, 80.7% avoided the activity entirely. Many women used pads (49.2%). Interest in pelvic floor physiotherapy to improve their UI was high (84.6%), but 63.5% of women still sought pessary or surgical management. Unfortunately, 35.6% of the women had no idea treatment was even an option.

Nygaard & Shaw (2016) reviewed and summarized the cross-sectional studies regarding the association between physical activity and pelvic floor disorders. Trampolinists, especially those in the 3rd tertile of competition, even those who were nulliparous, experienced greater leakage. Competitive athletes in the highest quartile of time exercising were found to have 2.5 times the amount of urinary incontinence (UI) as the lowest inactive quartile; however, 2nd and 3rd quartile recreational athletes had no difference in UI compared to inactive women. Type and dosage of exercise were both factors in UI risk. Various studies showed habitual walking decreased UI in older women, moderate exercise decreased the risk of UI, and no exercise increased the risk of UI. The incidence of UI being related to having performed strenuous exercise early in life has been limited and variable, with one study of Norwegian athletes and US Olympians not having any greater UI later in life, while another showed middle-aged women who used to exercise 7.5 hours per week had a higher incidence of UI. This review also reported athletes had a 20% greater cross sectional area of the levator ani muscle and a greater pubovisceral muscle mean diameter; however, the pelvic floor strength recorded was lower than non-athletes.

Interestingly, Leitner et al. (2017) explored pelvic floor muscle activation for continent and incontinent females during running. For 10 seconds, EMG tripolar vaginal probe recorded activity at 7, 11, and 15km/h. No statistically significant differences between continent or incontinent subjects were found for the EMG values. Pre-activity and reflex activity mean EMG increased significantly with speed; mean pelvic floor muscle EMG activity during running was significantly above onset activation value; and, maximum voluntary contraction was exceeded 100% for all time intervals at 15km/h in women with UI. These authors suggested the stimulus of running could actually be beneficial in pelvic floor muscle training considering the reflex activity of the muscles.

At races now, I still silently survey my competition, but now I am more curious as to how many women are actually able to complete the run without leakage. The prevalence of UI among athletes continues and is becoming more of an open topic of conversation. The research as to how much and which kind of exercise correlates with UI or what activity and level of participation may be preventative for UI is growing. The need for pelvic floor therapists to treat athletes who are fit to be dry is ever increasing.

Brennand, E., Ruiz-Mirazo, E., Tang, S., Kim-Fine, S., Calgary Women’s Pelvic Health Research Group. (2017). Urinary leakage during exercise: problematic activities, adaptive behaviors, and interest in treatment for physically active Canadian women. International Urogynecology Journal. http://www.doi:10.1007/s00192-017-3409-1

Nygaard, I. E., & Shaw, J. M. (2016). Physical Activity and the Pelvic Floor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 214(2), 164–171. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.067

Leitner M, Moser H, Eichelberger P, Kuhn A, Radlinger L. (2017). Evaluation of pelvic floor muscle activity during running in continent and incontinent women: An exploratory study. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 36:1570–1576. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23151

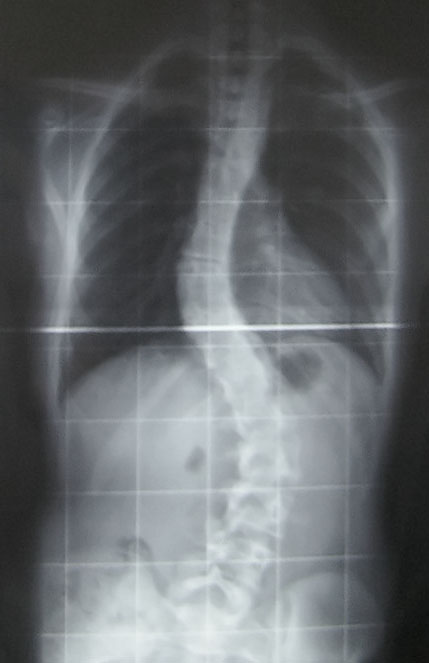

In some families, puberty is not only a time to have to deal with all the physical, hormonal, and emotional changes that are occurring, but it is a time to have to worry about and check for spinal abnormalities that can run in families. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is an abnormal curvature of the spine that appears in late childhood or adolescence. The spine will rotate, and a curvature will develop in an “S” shape or “C” shape. Scoliosis is the most common spinal disorder in children and adolescents. It is present in 2 to 4 percent of children between the ages of 10 and 16 years of age. There is a genetic link to developing scoliosis and scientists are working to identify the gene that leads to adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Adolescent girls are more likely to develop more severe scoliosis. The ratio of girls to boys with small curves of 10 degrees or less is equal, however the ratio of girls to boys with a curvature of 30 degrees or greater is 10:1. Additionally, the risk of curve progression is 10 times higher in girls compared to boys. Scoliosis can cause quite a bit of pain, morbidity, and if severe enough can warrant spinal surgery.

A recent article in Pediatric Physical Therapy by Zapata et al. assessed if there were asymmetries in paraspinal muscle thickness in adolescents with and without adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. They utilized ultrasound imaging to compare muscle thickness of the deep paraspinals at T8 and the multifidus at L1 and L4. They found significant differences in muscle thickness on the concave side compared to the convex side at T8 and L1 in subjects with scoliosis. They also found significantly greater muscle thickness on the concave side at T8, L1, and L4 in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis compared to controls. This is very interesting to me, and exciting to think about the possibilities of how we therapists might can use this information! My first question is, is the difference in muscle thickness a cause or result of the curvature of the spine? My next question is if we trained the multifidus on the convex side, the side that is thinner, would it make a difference in supporting the spine and therefore help prevent some of the curvature? Would strengthening the multifidus in a very segmental manner comparing right versus left and targeting segments and sides that are weaker than others help prevent rotation and curvature in individuals who have a familial predisposition to developing idiopathic scoliosis? I hope so! I hope this group continues to study scoliosis and provides some evidence-based treatment that can help decrease the severity of curvature.

A recent article in Pediatric Physical Therapy by Zapata et al. assessed if there were asymmetries in paraspinal muscle thickness in adolescents with and without adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. They utilized ultrasound imaging to compare muscle thickness of the deep paraspinals at T8 and the multifidus at L1 and L4. They found significant differences in muscle thickness on the concave side compared to the convex side at T8 and L1 in subjects with scoliosis. They also found significantly greater muscle thickness on the concave side at T8, L1, and L4 in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis compared to controls. This is very interesting to me, and exciting to think about the possibilities of how we therapists might can use this information! My first question is, is the difference in muscle thickness a cause or result of the curvature of the spine? My next question is if we trained the multifidus on the convex side, the side that is thinner, would it make a difference in supporting the spine and therefore help prevent some of the curvature? Would strengthening the multifidus in a very segmental manner comparing right versus left and targeting segments and sides that are weaker than others help prevent rotation and curvature in individuals who have a familial predisposition to developing idiopathic scoliosis? I hope so! I hope this group continues to study scoliosis and provides some evidence-based treatment that can help decrease the severity of curvature.

Assessing the multifidus thickness and strength, and differentiating it from the paraspinal muscles can be tricky. The best way to do this is the same way the authors of this article did, using ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound imaging gives unparalleled information on muscle shape, size, and activation of the muscle. Learning to use ultrasound imaging will change your practice! You will see dramatic differences in how you treat patients as well as the results you get when training the local core musculature. It also may open doors to treating different patient types than you are treating now, like adolescents with scoliosis. Join me in Spokane, WA on October 20-22 to further discuss how ultrasound can change your practice and perhaps help you reach out to a new population that you may not be treating now!

Miller NH. Cause and natural history of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:343–52.

Roach JW. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:353–65.

Zapata KA, Wang-Price SS, Sucato DJ, Dempsey-Robertson M. Ultrasonographic measurements of parspinal muscle thickness in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a comparison and reliability study. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2015; 27(2): 119-25.

The first time I experienced the effects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was when my patient dissociated during a treatment session and relived the rape that had occurred when she was ten years old. It was devastating. I didn’t know what to do. She was unresponsive to my intervention. Her eyes didn’t see me, alternating between wide-eyed, horrified panic and clenched-closed, lip biting excruciating pain. It was my late night and I was alone in the clinic. I sat helplessly next to my sweet patient hoping and praying that her torture would end quickly. When she finally stopped writhing, she slept. Deep and hard. Finally she woke up disoriented and scared. She grabbed her things and left. For me, this experience was my initiation into the world of trauma.

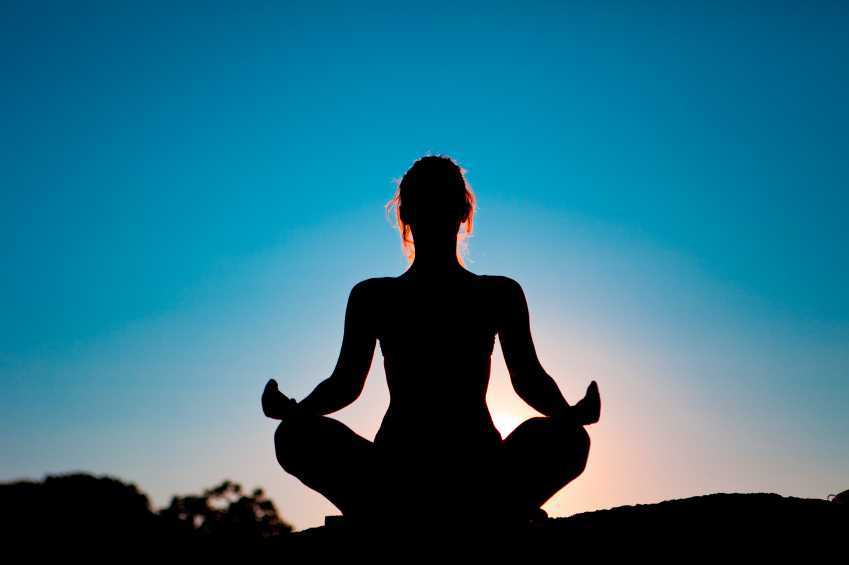

Approximately 5-6 % of men and 10-12% of women will suffer from PTSD at some point in their lives. Researchers believe that 10% of people exposed to trauma will go on to develop PTSD. The expression of PTSD symptoms can present differently in men and women. Men may have more externalizing disorders progressing along a scale that includes vigilance, resistance, defiance, aggression and homicidal thoughts. Women tend to present with internalizing disorders such as depression, anxiety, exaggerated startle responses, dissociation, and suicidal thoughts. The research is clear that both men and women with PTSD display changes in brain function. The mid brain (amygdala, basal ganglia and hippocampus) tends to be overactive in sounding alarm signals while the prefrontal cortex fails to turn off the mid brain when a threat is no longer present. Since the prefrontal cortex is not always functioning correctly, traditional talk therapy may not be as effective for treating PTSD. Instead, say many researchers, breath and movement exercises may help regulate brain functioning. Yoga, Tai Chi, and meditation have been shown to have a positive impact on down regulating the mid brain and improving cerebral output. As pelvic floor therapists we deal with trauma on a daily basis, whether we know it or not. Although we are not trained in psychology, understanding PTSD and equipping ourselves with tools to support our patients is imperative for both our patients and ourselves.

Approximately 5-6 % of men and 10-12% of women will suffer from PTSD at some point in their lives. Researchers believe that 10% of people exposed to trauma will go on to develop PTSD. The expression of PTSD symptoms can present differently in men and women. Men may have more externalizing disorders progressing along a scale that includes vigilance, resistance, defiance, aggression and homicidal thoughts. Women tend to present with internalizing disorders such as depression, anxiety, exaggerated startle responses, dissociation, and suicidal thoughts. The research is clear that both men and women with PTSD display changes in brain function. The mid brain (amygdala, basal ganglia and hippocampus) tends to be overactive in sounding alarm signals while the prefrontal cortex fails to turn off the mid brain when a threat is no longer present. Since the prefrontal cortex is not always functioning correctly, traditional talk therapy may not be as effective for treating PTSD. Instead, say many researchers, breath and movement exercises may help regulate brain functioning. Yoga, Tai Chi, and meditation have been shown to have a positive impact on down regulating the mid brain and improving cerebral output. As pelvic floor therapists we deal with trauma on a daily basis, whether we know it or not. Although we are not trained in psychology, understanding PTSD and equipping ourselves with tools to support our patients is imperative for both our patients and ourselves.

You might be wondering what happened after that frightful night in the clinic? My patient was determined to get better. She had a non-relaxing pelvic floor. She was a teacher and was plagued by urinary distress. She either had terrible urgency or would go for hours and not be able to empty her bladder. So we met with her therapist to learn strategies to help us to be able to work together without triggering dissociation. It was a slow road, but the three of us working together helped my patient not only reach her goals but to be able to be skillful enough to maintain her gains using a dilator for self-treatment.

If you would like to learn more about PTSD, meditation, yoga, chronic pain, psychologically informed practice and self-care for patients and providers please join Nari Clemons and I in Tampa in January as we present a new offering for Herman and Wallace, “Holistic Intervention and Meditation.” We would love to see you there.

Bremner, J. D. (2006). Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 8(4), 445-461.

Kerr, C. E., Jones, S. R., Wan, Q., Pritchett, D. L., Wasserman, R. H., Wexler, A., ... & Littenberg, R. (2011). Effects of mindfulness meditation training on anticipatory alpha modulation in primary somatosensory cortex. Brain research bulletin, 85(3), 96-103.

Morasco, B. J., Lovejoy, T. I., Lu, M., Turk, D. C., Lewis, L., & Dobscha, S. K. (2013). The relationship between PTSD and chronic pain: mediating role of coping strategies and depression. Pain, 154(4), 609-616.

Olff, M., Langeland, W., & Gersons, B. P. (2005). The psychobiology of PTSD: coping with trauma. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(10), 974-982.

The Role Of Yoga In Healing Trauma

Examples of pranayama

Ujjayi

Letting Go Breath

Integrating into the clinic

1) Iyengar BKS. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Schocken; 1995.

2) Sapsford RR, Richardson CA, Maher CF, Hodges PW. Pelvic floor muscle activity in different sitting postures in continent and incontinent women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(9):1741-1747.15.

3) Julie Wiebe, Physical Therapist | Educator, Advocate, Clinician. 2015; http://www.juliewiebept.

4) Talasz H, Kremser C, Kofler M, Kalchschmid E, Lechleitner M, Rudisch A. Phase-locked parallel movement of diaphragm and pelvic floor during breathing and coughing-a dynamic MRI investigation in healthy females. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(1):61-68.

5) Sapsford R. Rehabilitation of pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. Man Ther. 2004;9(1):3-12.

6) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

7) Massery M. THE LINDA CRANE MEMORIAL LECTURE: The Patient Puzzle: Piecing it Together. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2009;20(2):19-27.

8) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

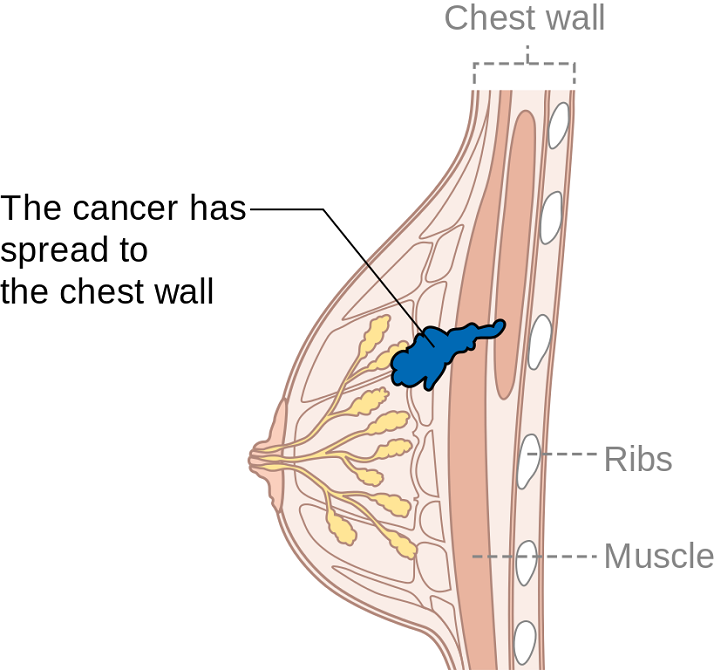

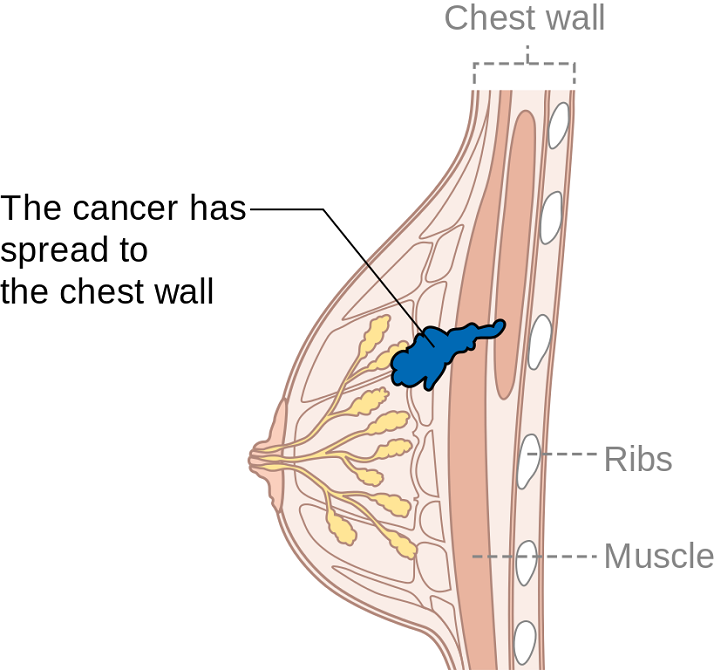

Summer can make women cringe at the thought of baring most of their bodies yet finding just the right coverage for their breasts. Some scrounge for padded tops to pump up their actual A cup. Some seek the greatest amount of coverage to support every ounce of skin. And still others search for flattering tops to accentuate cleavage and minimize tan lines. Just like one swimsuit does not fit every woman, only one aspect of post-breast cancer rehab is not generally sufficient. A combination of exercise, mindfulness, and myofascial release may need to be implemented for optimal recovery.

Ibrahim et al., (2017) produced a pilot randomized controlled trial considering the effects of specific exercise on upper limb function and ability to return to work after radiotherapy for breast oncology. The study involved 59 young women divided into an exercise group or a control group that received standard care. The Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH), the Metabolic Equivalent of Task-hours per week (MET-hours/week), and a post hoc questionnaire on return to work were all used and recorded over 6 time periods after the 12-week post-radiation targeted exercise program. Women who had a total mastectomy still had upper limb dysfunction, but no there was no statistically significant difference in DASH scores between groups. Both groups at 18 months had returned to their pre-illness activity levels, and 86% returned to work (at just 8.5 fewer hours/week). The authors concluded exercise alone does not change the long-term outcome of upper limb function post-radiation.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for persistent pain in women after treatment for primary breast cancer was explored by Johannsen et al., in two 2017 articles, one concerned with clinical and psychological mediators and the other focused on cost-effectiveness. Each study included 129 women with persistent pain from breast cancer, placed in a MBCT group or a wait-list control group. The first study showed attachment avoidance was a statistically significant moderator, with subjects who had a higher attachment avoidance having lower pain intensity after MBCT. In the subjects undergoing radiotherapy, MBCT had a smaller effect on pain than those not having radiotherapy. The authors’ next study focused on the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) on pain intensity. Baseline and 6 months post-treatment data on healthcare utilization and pain medication were analyzed from national registries. The average total cost of the MBCT group was 730 euros less than the control group, and more women in the MBCT group had a MCID in pain than those in the control group.

DeGroef et al., (2017) performed a randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of myofascial techniques for breast cancer survivors who experienced upper limb dysfunctions. Fifty women post-unilateral breast cancer received either 12 sessions of standard physical therapy with myofascial therapy or 12 sessions of standard physical therapy plus a sham intervention during a 3-month period. After intervention, no significant differences between groups were found for active shoulder range of motion, lymphedema, handheld dynamometer strength, scapular statics and dynamics, shoulder function, or quality of life. The authors concluded shoulder ROM and function in both groups showed positive effects up to 1 year follow-up, but myofascial therapy provided no additional benefit in breast cancer patients.

Treatment for any patient should be individualized, based on deficits found clinically, whether they are physiological, anatomical, or psychological. Having a beach bag overflowing with techniques and tools, each ready to be used when the appropriate time comes, makes for a more competent therapist and a better rehabilitation outcome for patients. There simply is no “one size fits all” in breast oncology rehab.

YOU can be a major contributor to a breast cancer patients medical care team. Learn new skills by attending Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient this September in Boston, MA.

Ibrahim, M, Muanza, T, Smirnow, N, Sateren, W, Fournier, B, Kavan, P, Palumbo, M, Dalfen, R, Dalzell, MA. (2017). Time course of upper limb function and return-to-work post-radiotherapy in young adults with breast cancer: a pilot randomized control trial on effects of targeted exercise program. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: research and practice. http://doi:10.1007/s11764-017-0617-0

Johannsen, M, O'Toole, MS, O'Connor, M, Jensen, AB, Zachariae, R. (2017). Clinical and psychological moderators of the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on persistent pain in women treated for primary breast cancer - explorative analyses from a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncology. 56(2):321-328. http://doi:10.1080/0284186X.2016.1268713

Johannsen, M, Sørensen, J, O'Connor, M, Jensen, AB, Zachariae, R. (2017). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is cost-effective compared to a wait-list control for persistent pain in women treated for primary breast cancer-Results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. http://doi:10.1002/pon.4450

De Groef,A, Van Kampen, M, Verlvoesem N, Dieltjens, E, Vos, L, De Vrieze, T, Christiaen, MR, Neven, P, Geraerts, I, Devoogdt, N. (2017). Effect of myofascial techniques for treatment of upper limb dysfunctions in breast cancer survivors: randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 25(7):2119-2127. http://doi:10.1007/s00520-017-3616-9

Preterm birth can have deleterious health effects not only for the child, but also for the mother. A child may be born so early that various health systems are not matured, leading to susceptibility and delay in development and growth. Maternal health may also be severely impacted, with conditions such as anxiety and psychological stress. Managing the prevention of a pre-term delivery can be stressful and challenging for a pregnant woman, and authors Ha & McDonald (2016) report that this issue is not well studied. A cross-sectional survey was completed to find out not only what a woman’s preferences and concerns are, but also to find out which recommendations were likely to be followed by the patient. This is important, the authors state, because women who are actively involved in medical decisions are more likely to feel satisfied with their childbirth experience.

The survey was completed by 311 women at a median of 32 weeks gestation. Mean age was 30.9, and the majority of them identified as European/White-Caucasian. Most of them were married or in a common-law relationship and had received some level of post-secondary education. The majority of women who were told they were at increased risk of preterm labor (PTL) preferred close-monitoring rather then PTL prevention. Of interest is that the majority of women reported they would use other sources of information besides their primary provider, with the most reported source being the internet or family and friends. This point begs the question of how high is the quality level or accuracy of the available information on the internet or in the general public? Common available options for prevention included progesterone, cerclage, and pessary use. If a woman is not interested in using recommended prevention strategies, the goal of the rehabilitation clinician should be to, on a constant basis, monitor for symptoms and signs of early labor, and encourage the patient to keep any recommended provider appointments, and stay in close contact with her provider so that close-monitoring may be carried out.

An additional goal for rehabilitation is to provide the mother with strategies that may assist her in managing her anxiety, stress, movement dysfunctions, sleep, and other activities. Prior research has validated the benefits of relaxation training in pre-term labor: a cost-effective, low risk and easily implemented strategy. Training women in such a tool during pregnancy fits well into the rehab provider’s scope, and can be instructed in the clinic (or home!) for home program implementation. Larger newborns, longer gestations, and higher rates of prolonged gestations have been recorded when using relaxation training training for pre-term labor.Janke et al., 1999) Chuang et al. (2012) have documented fewer admissions to neonatal intensive care unit, decreased rates of extreme pre-term birth, and shorter stays in hospital with use of relaxation training. Meditation, mindfulness, deep breathing, visualization, and movement within recommend medical limits may all be valuable tools that make up a part of a patient’s rehabilitation experience. In an article describing how prenatal meditation influences infant behaviors, yoga, singing, and massage therapy are all cited methods for improving maternal and/or fetal health.Chan, 2014

The Herman & Wallace Institute offers a three part series on pregnancy and postpartum. Get started by attending either Care of the Pregnant Patient or Care of the Postpartum Patient. You may also be interested in any of the Mindfulness & Meditation courses, including Holistic Interventions and Meditation, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, and Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals.

Chan, K. P. (2014). Prenatal meditation influences infant behaviors. Infant Behavior and Development, 37(4), 556-561.

Chuang, L.-L., Lin, L.-C., Cheng, P.-J., Chen, C.-H., Wu, S.-C., & Chang, C.-L. (2012). The effectiveness of a relaxation training program for women with preterm labour on pregnancy outcomes: A controlled clinical trial. [Article]. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49, 257-264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.007

Ha, V., & McDonald, S. D. (2017). Pregnant women’s preferences for and concerns about preterm birth prevention: a cross-sectional survey. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 17(1), 49.

Janke, J. (1999). The effect of relaxation therapy on preterm labor outcomes. Journal Of Obstetric, Gynecologic, And Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN / NAACOG, 28(3), 255-263.

Have you ever tried to teach a patient how to isolate their transversus abdominis (TA) contraction or a pelvic floor muscle (PFM) contraction and the patient had difficulty or you weren’t sure how well they were isolating it? Did you ever wish you had the ability to use real-time ultrasound (US) to confirm which abdominal layers they were isolating or use it for visual feedback to assist in your patient’s learning? Could it be helpful to be able to use real-time US to identify if they were isolating the pelvic floor muscles and give your patient visual feedback? Of course!

Real- time US has been used as an assessment and teaching tool to directly visualize abdominal and PFMs. PFM function can be assessed by observing movement at the bladder base and bladder neck. Various studies have used US on women with and without urinary incontinence (UI). These studies usually use transabdominal (TAUS) and transperineal (TPUS) ultrasound to measure if PFM isometrics or exercises are performed correctly or incorrectly, or how the muscles are functioning.

A 2015 study in the International Urogynecology Journal utilized TAUS to identify the ability to perform a correct elevating PFM contraction and assess bladder base movement during an abdominal curl up exercise. Abdominal curl ups are cited to increase intra-abdominal pressure. Activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure have been cited to provoke stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Abdominal curl ups are often completed in group exercise classes and have been found to provoke SUI in up to 16% of women.

Use of PFM exercises and of “the knack” (performing an isometric pelvic contraction before an exertional activity where intra-abdominal pressure increases, such as before lifting or coughing) has been shown to help manage stress urinary incontinence.

The theory is that elevation of the PFMs during activities that increase intraabdominal pressure (like a curl up) assist in urethral closure and counter act the downward movement, therefore stabilizing the urethra and bladder neck. When using TAUS, while performing a correct PFM contraction, one might expect to see an elevating PFM contraction. In the study, TAUS was used on 90 women participating in a variety of group exercise classes. The participants completed a survey and then three attempts of an abdominal curl up exercise in hooklying. During the curl ups, bladder base displacement was measured to determine correct or incorrect activation patterns. It was found that 25% of the women were unable to demonstrate an elevating PFM contraction, and all women displayed bladder base depression on the abdominal curl exercise. It was also found that parous women displayed more bladder base depression than nulliparous women, and overall 60% of the participants reported SUI. Lastly, this study found there was no association between SUI and the inability to perform an elevating PFM contraction or the amount of bladder base depression.

What interesting information. Using real time US in the clinic could help us identify if our patients were completing “the knack” correctly with specific activities. This study is a great example of how we can use real time US to help collect evidence to provide us with more information that can help us answer our own questions, patient questions, and improve our instructional methods to patients when teaching core or PFM exercises.

1) Barton, A., Serrao, C., Thompson, J., & Briffa, K. (2015). Transabdominal ultrasound to assess pelvic floor muscle performance during abdominal curl in exercising women. International urogynecology journal, 26(12), 1789-1795.

“To me it felt like I was just sitting on bed rest, waiting to have a seizure, you know, waiting to start circling the drain.” “Every time I went to the doctor I had this…anxiety attack.” These are the words of pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia and on bed rest. Other phrases reported by the authors who interviewed women on bedrest included “…an impending doom…”, “…meltdown…”, “nervous wreck.” A few of the major themes that emerged in the interviews was that of negative thoughts and feelings, family stressors, and not being heard. And while using the term “crazy” is not truly appropriate, women who are forced to abruptly stop interacting and participating in their typical life activities must be regarded as being very high risk for more than just physical issues. Kehler et al., 2016

In an ideal situation, bed rest during pregnancy is prescribed to help keep the mother and fetus healthy. Unfortunately, bed rest in itself is associated with potentially negative consequences in physical and mental health, and providers are not always up-to-date on changing recommendations for bedrest. Perhaps the cautious attitude of providers towards minimizing risk guides some choices. In addition, many women describe frustration about lack of clear guidelines, difficulty managing their stressful feelings, and varying degrees of support from medical providers.

In an ideal situation, bed rest during pregnancy is prescribed to help keep the mother and fetus healthy. Unfortunately, bed rest in itself is associated with potentially negative consequences in physical and mental health, and providers are not always up-to-date on changing recommendations for bedrest. Perhaps the cautious attitude of providers towards minimizing risk guides some choices. In addition, many women describe frustration about lack of clear guidelines, difficulty managing their stressful feelings, and varying degrees of support from medical providers.

During pregnancy-related bed rest, research has described how the entire family is affected. Physically, the mother may have changes in her circadian rhythms, increased anxiety, depression, and hostility. The rest of the family can also experience and demonstrate stress. Other children may act out, partners may be more stressed and worried, and financial strain may be a concern. Bigelow & Stone, 2011 Although we as rehab professionals may not have solutions for every issue, we may be able to facilitate accessing resources and at a minimum hear what a woman is dealing with during this stressful time. Many women, even when on bedrest, are allowed to attend medical appointments such as physical therapy, and should be provided with appropriate physical and mental activities to help minimize muscle atrophy and stress. Home health or hospital-based providers are also in a perfect position to educate providers on the value of referrals while the patient is at home or in the hospital.

We should keep these issues in mind during pregnancy as well as in the postpartum period. Maloni & Park (2005) measured postpartum symptoms in women who were on bedrest during pregnancy, and at 6 weeks postpartum, 40% of the 106 women (high-risk, singleton) complained of mood changes, difficulty concentrating, and other physical issues. Women who had a c-section had worsened symptoms, and the length of time on bed rest was highly correlated with the number of symptoms.

Bed rest affects a woman’s cognition, creates fear, a sense of lack of control, powerlessness, and even anger. “Because of this, Rodrigues and colleagues (Rodrigues et al., 2016) suggest that “…mental disorders should be routinely investigated during high-risk pregnancy, whenever possible with the use of specific instruments so that they can be detected early and so that interventions can be made in due time.” If you are interested in discussing this issue and many others, check out the Institute’s continuing education choices in peripartum health. The next Care of the Postpartum Patient course is taking place on September 16-17, 2017 in Nashville, TN.

Bigelow, C., & Stone, J. (2011). Bed rest in pregnancy. The Mount Sinai Journal Of Medicine, New York, 78(2), 291-302. doi: 10.1002/msj.20243

Kehler, S., Ashford, K., Cho, M., & Dekker, R. L. (2016). Experience of Preeclampsia and Bed Rest: Mental Health Implications. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(9), 674-681.

Maloni, J. A., & Park, S. (2005). Postpartum Symptoms After Antepartum Bed Rest. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 34(2).

Meher, S., Abalos, E., & Carroli, G. (2005). Bed rest with or without hospitalisation for hypertension during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4.

Rodrigues, P. B., Zambaldi, C. F., Cantilino, A., & Sougey, E. B. (2016). Special features of high-risk pregnancies as factors in development of mental distress: a review. Trends in psychiatry and psychotherapy, 38(3), 136-140.

Everyone experiences constipation, sometime! Maybe it was on vacation and you felt bloated and miserable; or when you were busy at work and had to rush to complete a task. In any event, you felt ‘awful’. Maybe you couldn’t zip your favorite jeans due to abdominal bloating, maybe you experienced lower abdominal discomfort or experienced a painful ‘movement’ once you went. There are many people who experience these symptoms and more on a daily basis. When someone finally gets the courage to see a specialist about this problem, they might be diagnosed with ‘pelvic floor dyssynergia’ or ‘muscle incoordination’.

Pelvic muscle dyssysnergia (incoordination) refers to the action that occurs in the pelvic floor musculature at the time of defecation. It can become a withholding pattern and in the case of vacation or a change in your work schedule, it can simply be tensing the muscle to avoid the bowel movement (due to inconvenience) rather than heeding the ‘call’. Over time, if this behavior is repeated, it becomes muscle memory; instead of relaxing the pelvic muscle to defecate, the patient tenses the muscle; thus the term dyssynergia or incoordination. The function of the pelvic floor for bowel function is to provide closure of the anal canal to maintain continence. The muscle should signal the rectum and the colon when to defecate and should provide opening of the anal canal by total relaxation to allow for complete and effortless elimination. A dyssynergic pattern shuts the opening of the canal by tensing the muscle to prevent elimination. Thus an incoordination.

The research by Heymen, Scarlett, Ringman, Drossman et al entitled “Randomized, Controlled Trial Shows Biofeedback to Be Superior to Alternative Treatments for Patients with Pelvic Floor Dyssynergia-Type Constipation” supports the value of biofeedback in the treatment of this withholding pattern associated with stool elimination. This study supports the benefit of biofeedback treatments using internal sensors to provide the feedback displayed on a computer screen for visualization. This study goes on to say, “We also have shown that the machines are necessary—instrumented biofeedback is an essential element of successful training; however, there is a shortage of practitioners who are trained to provide this form of biofeedback, and there are few clinics where biofeedback instruments are available and where this form of biofeedback can be obtained”.

Biofeedback provides visual and auditory feedback of muscle tension. It is a non-invasive technique that allows patients to adjust muscle function, strength, and behaviors to improve pelvic floor function. The small electrical signal (EMG) provides information about an unconscious process and is presented visually on a computer screen, giving the patient immediate knowledge of muscle function, enabling the patient to learn how to alter the physiological process through verbal and visual cues. This mechanism allows the patient to assess muscle resting tone, creating an environment that teaches how to downtrain a tense pelvic floor while providing the means to teach co-ordination of muscle function.

In short, biofeedback treatment/training using the proper instrumentation provides the precise information necessary to change behaviors associated with tensing the pelvic floor for defecation instead of the proper relaxation of the pelvic floor for release of stool from the anal canal.

The Herman Wallace Course on Biofeedback Training for Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction provides the clinician with the proper treatment technique to use in the clinic to rehabilitate patients with pelvic floor muscle dyssynergia. Learning the proper use of biofeedback equipment and understanding the components to treating these challenging patients successfully is an essential component to this course. The clinician will learn numerous ways to teach this challenging patient population how to make this muscle function as intended, providing the patient with successful strategies for improved patient outcomes.