An 80 year old lady who had seen a physical therapist where I once worked in Naperville, IL, just completed a marathon and a 5k race in one weekend. She is undoubtedly one woman who can change our perception of the “elderly,” but we all know her strength and ability are not the norm. The geriatric patients coming to therapy for pelvic floor disorders are more likely to be too frail to have run a mile this century, and they are most likely struggling with functional ADLs, as research suggests.

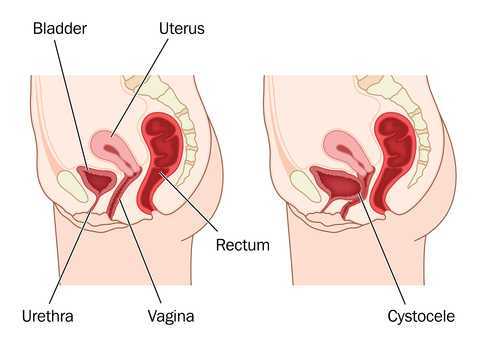

A study by Erekson et al., (2015) looked into the prevalence of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability among women over 65 years of age looking for the best treatment for their pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). A major concern was the presence of frailty being equated with poorer surgical outcomes. The 150 women in the study were tested with the Fried Frailty Index to measure frailty, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Score for cognitive screening, and the Katz ADL score for functional status. Pelvic organ prolapse was present in 65.3% women, urinary incontinence in 20.7%, overactive bladder in 9.3%, and anal incontinence in 0.7%. Sixteen percent of women were considered frail and 42% were “prefrail.” Dementia was determined in 21.3% of women, and functional disability in 30.7%. Pelvic floor dysfunction in women with frailty caused a significantly greater life-impact than in normal and pre-frail women. Forty-six percent of the subjects opted for surgery, but only women with functional disability, not impaired cognition nor frailty, were less likely to choose non-surgical intervention. The authors concluded that being able to identify women with PFD with risk factors of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability may help predict the risk of complications before surgery and help encourage behavioral changes and provide the appropriate pre and post-operative care for each woman.

A study by Erekson et al., (2015) looked into the prevalence of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability among women over 65 years of age looking for the best treatment for their pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). A major concern was the presence of frailty being equated with poorer surgical outcomes. The 150 women in the study were tested with the Fried Frailty Index to measure frailty, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Score for cognitive screening, and the Katz ADL score for functional status. Pelvic organ prolapse was present in 65.3% women, urinary incontinence in 20.7%, overactive bladder in 9.3%, and anal incontinence in 0.7%. Sixteen percent of women were considered frail and 42% were “prefrail.” Dementia was determined in 21.3% of women, and functional disability in 30.7%. Pelvic floor dysfunction in women with frailty caused a significantly greater life-impact than in normal and pre-frail women. Forty-six percent of the subjects opted for surgery, but only women with functional disability, not impaired cognition nor frailty, were less likely to choose non-surgical intervention. The authors concluded that being able to identify women with PFD with risk factors of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability may help predict the risk of complications before surgery and help encourage behavioral changes and provide the appropriate pre and post-operative care for each woman.

Silay et al., (2016) published a review on urinary incontinence (UI) in elderly women, relating its association with other geriatric conditions. Sixty-four females aged 65 and older were evaluated using the Turkish version of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) to assess UI and quality of life. Activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) were used to evaluate functional status, and the Mini Mental State Examination was used for cognitive assessment. The comorbidities, pharmaceuticals, falls, and body mass index (BMI) of patients were also recorded. Results showed the subjects’ rate of urinary incontinence was 40.6%, and 28.1% of the women had their quality of life impacted. There was a statistically significant association using logistic regression between UI and quality of life, functional status, and comorbidity. Sadly, 50% of patients thought UI was normal with aging, 34.6% had been embarrassed to tell anyone about it, and 15.3% said they did not know UI was something for which medical treatment could be given.

Understanding how to manage frailty, cognitive issues, and functional deficits of our elderly patients can positively impact treatment outcomes. We should always strive to educate our patients and be aware of conditions that may be affecting or even contributing to their PFD. The Geriatric Pelvic Floor Rehab course can enlighten therapists on a score of comorbidities and techniques for handling those patients who are not sporting a marathon finisher medal to their physical therapy visits!

Erekson, E. A., Fried, T. R., Martin, D. K., Rutherford, T. J., Strohbehn, K., & Bynum, J. P. W. (2015). Frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability in older women with female pelvic floor dysfunction. International Urogynecology Journal, 26(6), 823–830. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2596-2

K. Silay, S. Akinci, A. Ulas, A. Yalcin, Y.S. Silay, M.B. Akinci, I. Dilek, B. Yalcin. (2016). Occult urinary incontinence in elderly women and its association with geriatric condition. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 20(3): 447-451.

When my 6 year old daughter ran to the bathroom 3-4 times before she got on the school bus every morning, I wasn’t too concerned, but I definitely took note. The day she was in tears and wouldn’t get off the toilet because she felt like she was still wet, I got worried (although slightly intrigued). No matter how much she wiped, she still felt wet. When she stood up, she felt like she was going to pee herself, making my sweet-natured girl slip into hysterics. After eliminating small amounts of urine 8 separate times in 3 hours and saying it burned, I assumed she had a urinary tract infection (UTI). A simple urine test ruled out UTI or diabetes (thankfully!). So then, what was my daughter’s diagnosis? The pediatrician simply referred to it as “a phase;” however, I had researched the symptoms before the visit.

In 2014 Arlen et al. described a condition called “phantom urinary incontinence.” This refers to the situation when children experience the sensation of being wet (a presumptive urinary incontinence) when they are objectively dry. They considered 20 children (18 females, 2 males) referred to their pediatric urology clinic over a 5 year span, all who were all diagnosed with phantom urinary incontinence (PUI). The authors evaluated the concomitant diagnoses found among the boys and girls in the study. Lower urinary tract symptoms were present in 95% of the subjects. Associated bladder symptoms were found as well, with urgency in 75% and frequency in 50% of the children. Vaginitis occurred in 72% of the girls. Parents reported obsessive-compulsive disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder personality traits in 70% of the children. In order to treat these patients, dietary modifications, timed voiding, and a bowel regimen were implemented to manage symptoms. A follow up at 14.4 months revealed 90% of the children’s bowel-bladder dysfunction improved and PUI resolved. The authors concluded children compliant with a rigid bladder-bowel regimen experience relief of their “phantom” incontinence as well as lower urinary tract symptoms, and a majority of PUI patients have obsessive-compulsive traits.

In 2014 Arlen et al. described a condition called “phantom urinary incontinence.” This refers to the situation when children experience the sensation of being wet (a presumptive urinary incontinence) when they are objectively dry. They considered 20 children (18 females, 2 males) referred to their pediatric urology clinic over a 5 year span, all who were all diagnosed with phantom urinary incontinence (PUI). The authors evaluated the concomitant diagnoses found among the boys and girls in the study. Lower urinary tract symptoms were present in 95% of the subjects. Associated bladder symptoms were found as well, with urgency in 75% and frequency in 50% of the children. Vaginitis occurred in 72% of the girls. Parents reported obsessive-compulsive disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder personality traits in 70% of the children. In order to treat these patients, dietary modifications, timed voiding, and a bowel regimen were implemented to manage symptoms. A follow up at 14.4 months revealed 90% of the children’s bowel-bladder dysfunction improved and PUI resolved. The authors concluded children compliant with a rigid bladder-bowel regimen experience relief of their “phantom” incontinence as well as lower urinary tract symptoms, and a majority of PUI patients have obsessive-compulsive traits.

Oliver et al., (2013) studied how psychosocial comorbidities and body mass index relate to children with lower urinary tract dysfunction. Data on 358 patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction between 6 to 17 years old was collected, and the subjects’ parents completed questionnaires screening for lower urinary tract symptoms, stressful life events, and psychological comorbidities. Obesity was present in 28.5% of the children, 22.9% had a recent stress in life, and 22.9% had a psychiatric disorder. Under and overweight children, children with a recent life stressor, psychiatric disorder, or both, as well as the younger-aged children all had lower urinary tract symptom scores significantly higher than healthy weight subjects, those without psychosocial comorbidities, and older subjects. The results encourage screening for psychosocial issues and obesity in pediatric patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction.

Having read the research, I knew a life stressor was likely contributing to my daughter’s symptoms. I had already advised her to sit on the toilet every 1-2 hours, don’t let her bladder get too full, wipe gently from front to back, stop bubble baths, and wear looser pants. To conclude our $76 session, the doctor prescribed almost verbatim what my daughter had heard from me at home. Although thankful it wasn’t something more serious, I am curious what the diagnosis code is for “a phase” and when it will end.

Arlen, AM, Dewhurst, LL, Kirsch, SS, Dingle, AD, Scherz, HC, Kirsch, AJ. (2014). Phantom urinary incontinence in children with bladder-bowel dysfunction. Urology. 84(3):685-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2014.04.046 Oliver, J.L., Campigotto, M.J., Coplen, D.E. et al,. (2013). Psychosocial comorbidities and obesity are associated with lower urinary tract symptoms in children with voiding dysfunction. The Journal of Urology. 190:1511–1515. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.025

Perhaps you have seen the Facebook post by Alan Naughton (March 5, 2015) where a horse with one zebra leg tells another horse, “I can’t say I’m entirely pleased with my hip replacement.” Although this post makes some people laugh, I imagine surgical candidates cringe at the thought of complications. Few people hop onto a surgeon’s schedule with great enthusiasm. While hip replacements are sometimes inevitable for quality of life, other hip pathologies can be successfully treated with more conservative measures.

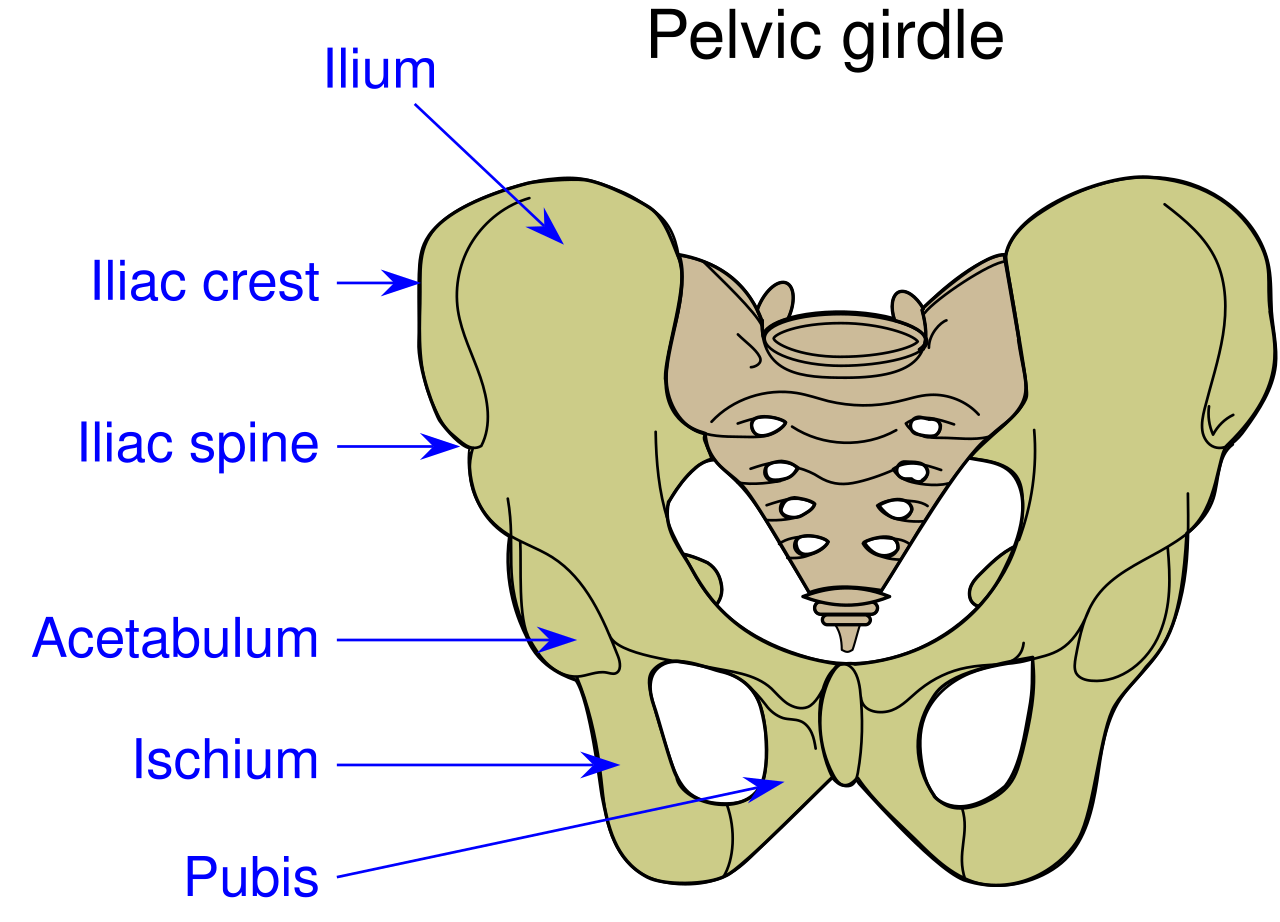

A case report in Manual Therapy (Lewis, Khuu, & Marinko 2015) described how postural correction and alternation of movement patterns were able to reduce hip pain secondary to acetabular dysplasia. A 31-year old female acute care nurse developed anterior hip pain with no trauma, and acetabular dysplasia as well as a labral tear were found. She got temporary relief of her constant ache and occasional sharp, intense pain from an intra-articular injection of cortisone. Her functional complaint was the pain prevented her from returning to recreational running. Intervention involved correcting the subject’s slight hip and knee hyperextension and posterior pelvic tilt with swayback posture, cueing her to walk on the treadmill with slight anterior pelvic tilt and contraction of the abdominals. This decreased her pain while walking from 6/10 to 2/10. Correction of the swayback posture decreased the hip flexion moment, decreasing stress on the anterior hip. At three months and then one year after the initial visit, she was relatively pain free. She still had pain with running, so she was advised to decrease her stride length and take shorter steps as well as decrease her hip extension by pushing off her feet more to minimize anterior hip joint reaction forces. With these cues, she was able to run without pain. Luckily for her, she had declined the option of acetabular reorientation surgery.

A case report in Manual Therapy (Lewis, Khuu, & Marinko 2015) described how postural correction and alternation of movement patterns were able to reduce hip pain secondary to acetabular dysplasia. A 31-year old female acute care nurse developed anterior hip pain with no trauma, and acetabular dysplasia as well as a labral tear were found. She got temporary relief of her constant ache and occasional sharp, intense pain from an intra-articular injection of cortisone. Her functional complaint was the pain prevented her from returning to recreational running. Intervention involved correcting the subject’s slight hip and knee hyperextension and posterior pelvic tilt with swayback posture, cueing her to walk on the treadmill with slight anterior pelvic tilt and contraction of the abdominals. This decreased her pain while walking from 6/10 to 2/10. Correction of the swayback posture decreased the hip flexion moment, decreasing stress on the anterior hip. At three months and then one year after the initial visit, she was relatively pain free. She still had pain with running, so she was advised to decrease her stride length and take shorter steps as well as decrease her hip extension by pushing off her feet more to minimize anterior hip joint reaction forces. With these cues, she was able to run without pain. Luckily for her, she had declined the option of acetabular reorientation surgery.

MacIntyre et al., (2015) presented a case study on conservative management of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) in a retired 22 year old elite ice hockey goaltender. A 4-year history of left anterior hip pain forced him into early retirement. He was diagnosed with longitudinal acetabular labral tears with a cam-type FAI. Before considering surgery, he had to undergo physical therapy, which he did 1-2 times per week for 6 weeks. Treatment consisted of Active Release Technique (ART)® and soft tissue therapy with tools directed to the affected gluteal , iliopsoas, and adductor muscles and fascial planes, spinal manipulation of the right sacroiliac joint, left hip capsule distraction/release using the Mulligan concept, contemporary medical electroacupuncture, and extensive rehabilitation exercises for lumbopelvic stability. After 8 visits, he had no pain at rest or with exercise. At 8 weeks he returned to playing ice hockey and now plays competitively again with no need for surgery.

I would venture to guess no one who takes the conservative route for treatment of hip dysfunction comes out of physical therapy with irreconcilable side effects. Being able to skip surgery using manual therapy and postural correction is a huge goal. If you doubt you can treat the hip effectively, taking Manual Therapy for the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip Complex can not only enhance your manual therapy approach to treatment but also introduce you to an exciting visual feedback system to maximize efficacy of core stabilization exercises.

Lewis, C. L., Khuu, A., & Marinko, L. (2015). Postural correction reduces hip pain in adult with acetabular dysplasia: a case report. Manual Therapy, 20(3), 508–512. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2015.01.014 MacIntyre, K., Gomes, B., MacKenzie, S., & D’Angelo, K. (2015). Conservative management of an elite ice hockey goaltender with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI): a case report. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 59(4), 398–409.

Anxiety and depression are frequently encountered co-morbidities in the clients we serve in pelvic rehabilitation. This observation several years ago in clinical practice is one of many that prompted me down the path of exploring the connection between the gut, the brain, and overall health. In answering the question about these connections, I discovered many nutritionally related truths that are being rapidly elucidated in the literature.

A recent study by Sandhu, et.al. (2017) examines the role of the gut microbiota on the health of the brain and it’s influence on anxiety and depression. The title of the study, “Feeding the microbiota-gut-brain axis: diet, microbiome, and neuropsychiatry” gives us pause to consider the impact of our diets on this axis and in turn, on the health of our nervous system. The authors state:

It is diet composition and nutritional status that has been repeatedly been shown to be one of the most critical modifiable factors regulating the gut microbiota at different time points across the lifespan and under various health conditions.

With diet and nutritional status being the most critical modifiable factors in the health of this system, it becomes our responsibility to seek to understand this system and its influencing factors. We need to learn how to nourish the microbiota-gut-brain axis.

While anxiety and depression are common co-morbidities we encounter, we also commonly detect imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system in our patients leading to, for example, pelvic floor muscle tension. In light of this study we must first and foremost ask: what is the microbiota? How can it influence our nervous system? How does this correlate to anxiety and depression? The answers to these questions provide clinical insight with far-reaching impact. We also consider: which circumstances disrupt the health of this system and which improve it? Finally, could understanding of this axis, among other nutritional correlates, provide a novel approach to bowel dysfunction, bladder dysfunction, chronic pelvic pain?

Be a part of the paradigm shift to integrative understanding as we explore these and many other burning questions. Please join us for insightful discussion in White Plains, NY March 31-April 1, 2017 for our next offering of Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist.

Sandhu, K. V., Sherwin, E., Schellekens, H., Stanton, C., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2017). Feeding the microbiota-gut-brain axis: diet, microbiome, and neuropsychiatry. Transl Res, 179, 223-244. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2016.10.002

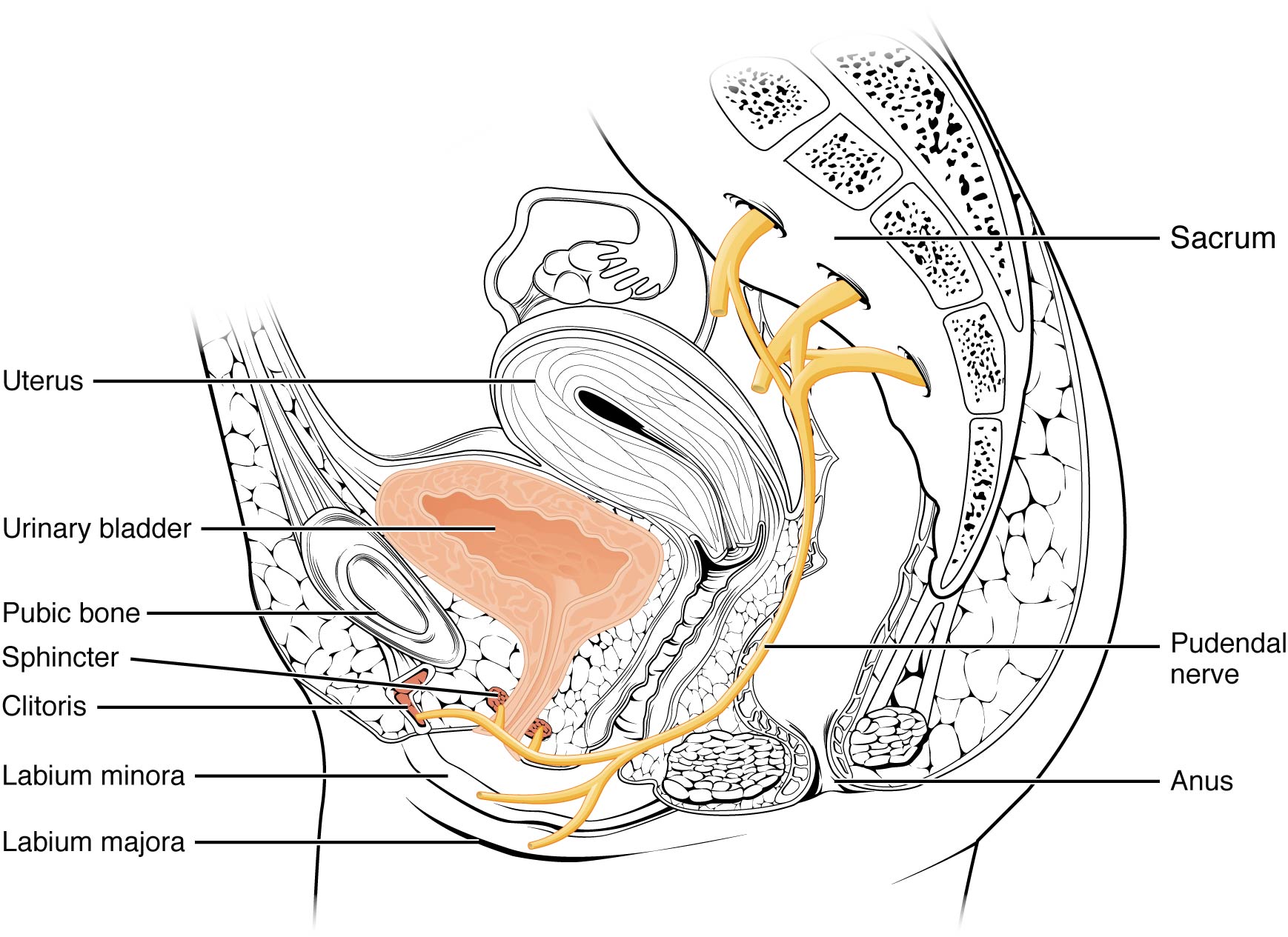

In the comedy, Kindergarten Cop, Detective John Kimble may only have had a headache, not a tumor, but sometimes our patients do have a tumor. One of my patients was actually just diagnosed with a brain tumor after responding poorly to a cortisone injection for her neck pain. Tumors in other areas of the body, even in the pelvis, can be the source of symptoms that may seem like a nerve entrapment. This is a serious consideration to be given when diagnosing pudendal neuralgia.

In 2008, Labat et al. published the “Diagnostic Criteria for Pudendal Neuralgia by Pudendal Nerve Entrapment” in Neurourology and Urodynamics . A group in Nantes, France, established criteria in 2006, since the diagnosis is primarily clinical in nature. The results of this paper concluded the five essential diagnostic criteria (Nantes criteria) are as follows:

In 2008, Labat et al. published the “Diagnostic Criteria for Pudendal Neuralgia by Pudendal Nerve Entrapment” in Neurourology and Urodynamics . A group in Nantes, France, established criteria in 2006, since the diagnosis is primarily clinical in nature. The results of this paper concluded the five essential diagnostic criteria (Nantes criteria) are as follows:

- Pain located in the anatomical region of the pudendal nerve.

- Pain worsened with sitting.

- Pain does NOT awaken the patient at night.

- Negative sensory loss upon clinical exam.

- Pain is relieved with an anesthetic pudendal nerve block.

A recent study by Waxweiler, Dobos, Thill, & Bruyninx explored the Nantes criteria as related to choosing surgical candidates for pudendal neuralgia from nerve entrapment. They looked at how a patient’s response to the anesthetic block corresponded to appropriate selection of patients for a successful surgical outcome. Six of 34 patients in the study had a negative anesthetic pudendal nerve block, and 100% of those patients had no symptom relief after surgery. In contrast, 64% of the patients who met all five of the Nantes criteria responded positively to surgery. The authors concluded confirmation of the 5th criteria as essential for predicting success of surgery for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment.

In Pain Physician in 2016, Ploteau et al. present two case studies where consideration of the Nantes criteria helped diagnose rare tumors in patients who demonstrated red flags during examination. Warning signs such as nocturnal awakening, point-specific pain, pain of a neuropathic nature, and neurological deficits cannot be overlooked when a patient presents with pudendal neuralgia. In the case studies presented, the 31 year old woman did not have pain exacerbated with sitting and woke at night with pain, and the 62 year old woman was awakened at night with pain. Each patient had magnetic resonance imaging performed, and rare diagnoses of endometrial stromal sarcoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma were made, respectively. The tumors arose in the ischiorectal fossa and compressed the pudendal nerve, presenting as pudendal neuralgia in atypical forms requiring careful clinical examination and referral for MRI for accurate diagnosis.

Although a tumor rarely exists, it is our duty to recognize signs and symptoms that do not follow established criteria. Paying attention to what your patients say just may be lifesaving. Proper diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia is essential and sometimes falls in our hands.

Labat, JJ., Riant, T., Robert, R., Amarenco, G., Lefaucheur, JP., Rigaud, J. (2008). Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourology and Urodynamics. 27(4):306-10. doi: 10.1002/nau.20505.

Waxweiler, C., Dobos, S., Thill, V., Bruyninx, L. (2016). Selection criteria for surgical treatment of pudendal neuralgia. Neurourology and Urodynamics. doi:10.1002/nau.22988.

Ploteau, S., Cardaillac, C., Perrouin-Verbe, M. , Riant, T., & Labat, J. (2016). Pudendal Neuralgia Due to Pudendal Nerve Entrapment: Warning Signs Observed in Two Cases and Review of the Literature. Pain Physician. 19:E449-E454.

What's the evidence, and what's the answer?

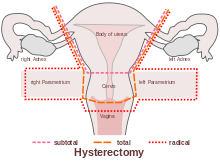

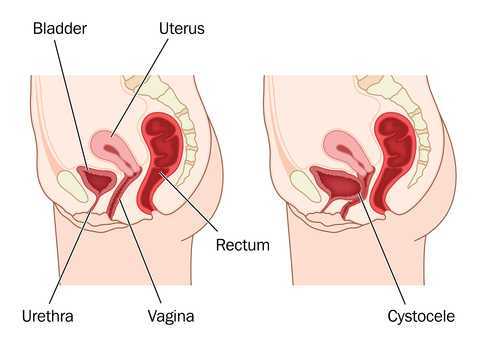

In getting ready to teach my Menopause course in Minneapolis next month, I always like to do a review of the evidence, to see what’s new, or what’s changed. What has changed over the past few years – more and more evidence to support the role of skilled rehab providers, using evidence based assessment techniques to gauge the grade of pelvic organ prolapse and assess the risk of levator avulsion. What hasn’t changed enough – the level of awareness of the benefits of pelvic rehab in managing, or in some cases even reversing, the effects and symptoms of prolapse.

Dr Peter Dietz, from the University of Sydney, writes ‘…although clinical anecdote suggests some physiotherapists recognize other characteristics suggesting muscle dysfunction (e.g. holes, gaps, ridges, scarring) or pelvic floor dysfunction (e.g. width between medial edges of pelvic floor muscle) with palpation it is difficult to find any literature describing the techniques needed to do this or their accuracy or repeatability. Mantle (in 2004) noted that with training and experience a physiotherapist might be able to discern muscle integrity, scarring, and the width between the medial borders of the pelvic floor muscles, with palpation. It is not clear to what extent physiotherapists are able to do this reliably or how such characteristics are to be recorded.’

Dr Peter Dietz, from the University of Sydney, writes ‘…although clinical anecdote suggests some physiotherapists recognize other characteristics suggesting muscle dysfunction (e.g. holes, gaps, ridges, scarring) or pelvic floor dysfunction (e.g. width between medial edges of pelvic floor muscle) with palpation it is difficult to find any literature describing the techniques needed to do this or their accuracy or repeatability. Mantle (in 2004) noted that with training and experience a physiotherapist might be able to discern muscle integrity, scarring, and the width between the medial borders of the pelvic floor muscles, with palpation. It is not clear to what extent physiotherapists are able to do this reliably or how such characteristics are to be recorded.’

Dr Dietz describes a palpation technique to assess the integrity of the pubovisceral muscle insertion, by checking the gap between the urethra centrally and the pubovisceral muscle laterally. On levator contraction this gap should be little wider than your index finger, otherwise an avulsion injury is very likely.

There is another aspect of levator assessment that can yield important information on clinical examination. The size of the levator hiatus can be estimated by determining the sum of the genital hiatus (gh) and perineal body (pb) in the context of the ICS POP-Q examination. Gh + pb, ie., the distance between the external urethral meatus and the centre of the anus, when measured on maximal Valsalva with a simple ruler, is highly predictive of symptoms and signs of prolapse, and it is very strongly correlated with hiatal area on Valsalva (Khunda et al., 2011).

Using this research, in the lab sessions of the Menopause course, we will review these palpation and measurement skills to give therapists the skills they need to confidently assess risk of levator avulsion and its impact on pelvic organ prolapse, and to use this information to devise a functionally appropriate rehab program.

Come and join the conversation in my course, Menopause Rehabilitation and Symptom Management!

Khunda A1, Shek KL, Dietz HP., Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;206(3):246.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.876. Epub 2011 Nov 7. Can ballooning of the levator hiatus be determined clinically?

How often have you heard that bedwetting was behavioral or caused by deep sleep and your child would outgrow it? 15% of children per year will “outgrow” bedwetting. What if your child is in the percentile at the end of that range?

Facts:

- Bedwetting affects 15% of girls and 22% of boys

- 5 - 7 Million US children

- Boys are 50% more likely than girls to wet the bed

- 10% of 6 year olds continue to wet

- Spontaneous cure rate 15% per year thereafter

- 1-3% of 18 year olds still wet their beds

- Less than 50% of all bedwetting children have bedwetting alone, without also experiencing daytime urinary leakage or constipation

- Bedwetting is genetic – if one parent was a bed wetter the child has a 40% chance of wetting the bed and if both parents were bedwetters the percentile goes up to 77%

Myths:

- Your child is lazy

- Your child is doing this to get attention

- Your child is just a deep sleeper

- You must wait to grow out of it

Research from the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) is a great resource for exploring the research on this topic and other pediatric voiding issues. www.i-c-c-s.org

What causes Bedwetting?

There are many philosophies discussed in the research. Here are some listed below:

- Hormone deficiency- our bladders empty about every 2-3 hours during the day however at night we can hold over 8 hours! This happens because our bodies produce an antidiuretic hormone when we sleep to slow kidney function and produce less urine to empty into the bladder. If this hormone is not being produced, the kidneys produce as much urine at night as they do during the day. In this case, it's good that the bladder empties out in our sleep, otherwise our bladders would be dangerously large and possibly reflux urine backward into the kidneys. Clearly not behavioral!!

- Dr. Steven Hodges has researched and written extensively on the topic of constipation causing pressure from the rectum against the bladder making it irritable during sleep. His research has supported the fact that once the bowel is cleaned out daily the bedwetting episodes diminish. See It’s No Accident by Dr. Hodges or visit https://www.bedwettingandaccidents.com for more information on this topic. Again, a physiological cause of bedwetting versus behavioral.

- Sleep Disturbance and Nasal Airway Obstruction. Dr. Neveus and colleagues reported that 43.5% of children with snoring or obstructive sleep apnea became dry after adenotonsillectomy. Dr. Kovacevic also found increases in antidiuretic hormone seen in responders post-operatively.

Take Home Message

- Active treatment for bedwetting should begin at age 6

- The impact of bedwetting is mainly psychological and may be severe

- Children with bedwetting have abnormal psychological test scores, however once the bedwetting is resolved the test scores return to normal

- “Treatment is not only justified but mandatory”

-ICCS Standardization document 2010

There is help!

At Physical Therapy Specialists we specialize in bedwetting, urinary leakage, constipation and other voiding issues in children. Let us eliminate the need for your family to suffer through this very treatable condition!

Al- Zaben FN, Sehlo MG. Punishement for bedwetting is associated with child depression and reduced quality of life. Child Abuse Negl. 2014

Hodges SJ, Colaco M. Daily enema regimen is superior to traditional therapies for nonneurogenic pediatric overactive bladder. Global Pediatric Health, 2016, 3: 1–4

Austin, P., Bauer, S.B., Bower, W., et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescence: update report from the standardization committee of the international children’s continence society. J Urol (2014) 191.

Treatment response of an outpatient training for children with enuresis in a tertiary health care setting. J Pediatr Urol. 2012.

Hodges SJ,Anthony EY::aunrecognizedof. Urology.2012 Feb;79(2):421-4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.10.015. Epub 2011 Dec 14.

Kovacevic L, Wolfe-Christensen C, Lu H, Toton M, Mirkovic J, Thottam PJ, Abdulhamid I, Madgy D, Lakshmanan Y. Why does adenotonsillectomy not correct enuresis in all children with sleep disordered breathing? J Urol. 2014 May;191(5 Suppl):1592-6.

Nevéus T, Leissner L, Rudblad S, Bazargani F. Acta Paediatr. 2014 Jul 15. doi: 10.1111/apa.12749. [Epub ahead of print]Orthodontic widening of the palate may provide a cure for selected children with therapy-resistant enuresis.

Hodges, Steve J. It’s No Accident-Breakthrough solutions for your child’s wetting, constipation, UTI’s and other potty problems. © 2012. Lyons Press, Guilford, Connecticut.

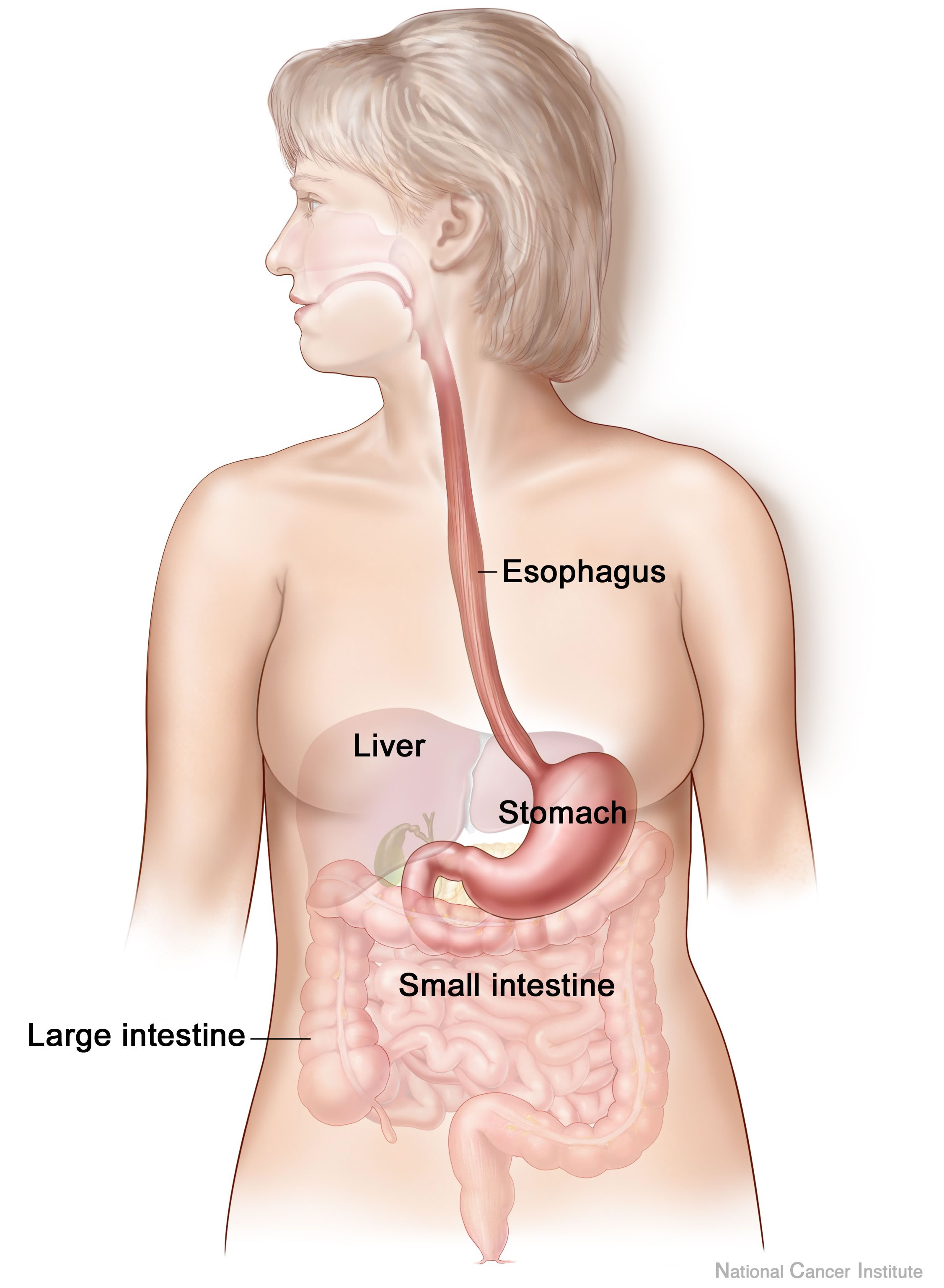

My manual therapist husband once wrote a paper on the visceral referral pattern of the liver. Although he knows I injured my right shoulder shoveling snow a few years ago, whenever I have an exacerbation of shoulder pain, he likes to joke it is from my liver. (I would laugh if I had not acquired an affinity for red wine since having kids!) Sometimes pain in remote areas of our body really can be related to an organ in distress or simply “stuck” because of fascial restrictions around it. The kidneys in particular can refer pain into the low back and hips, and the bladder and ureters can provoke saddle area pain.

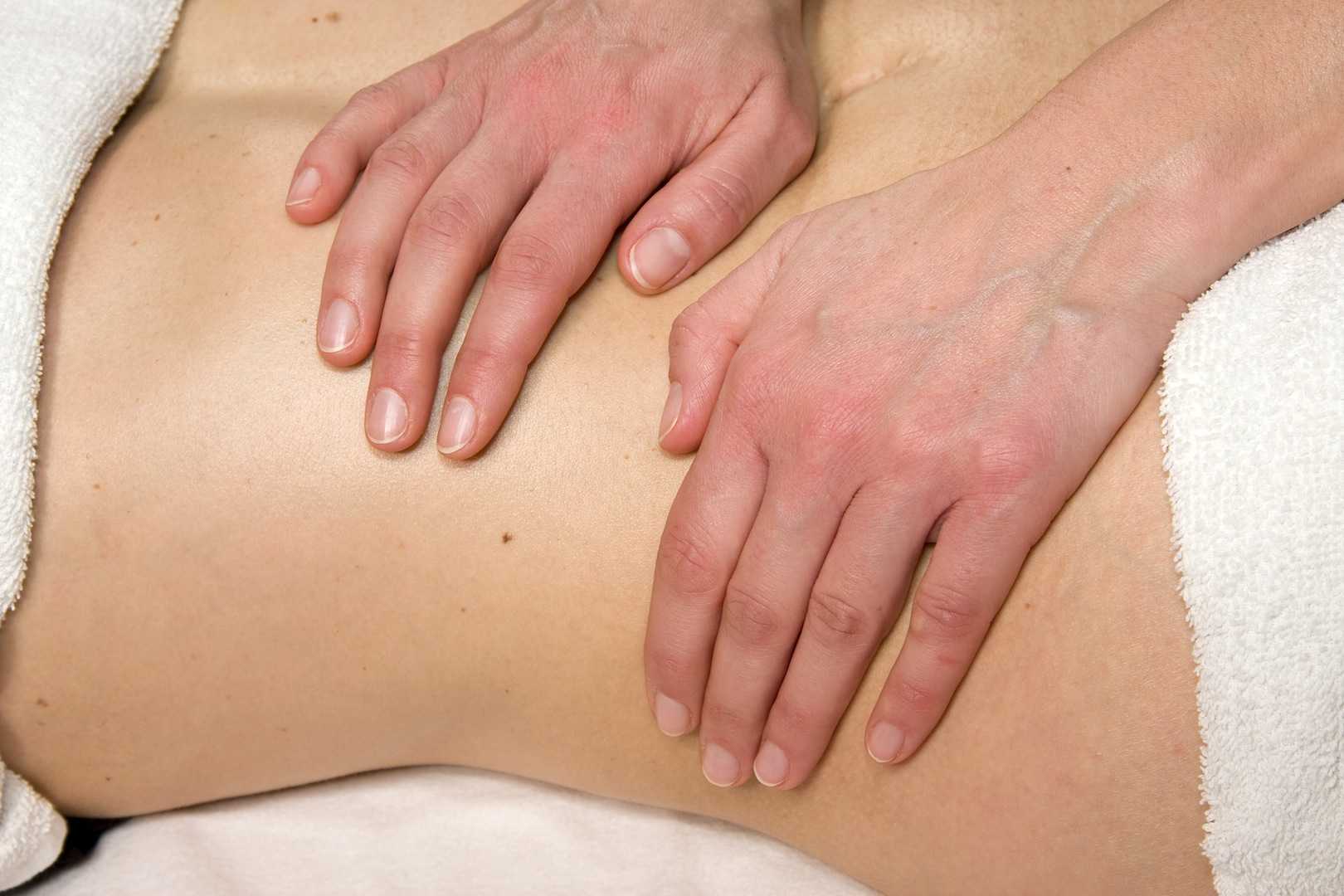

Tozzi, Bongiorno, and Vitturini (2012) looked into the kidney mobility of patients with low back pain. They used real-time Ultrasound to assess renal mobility before and after osteopathic fascial manipulation (OFM) via the Still Technique and Fascial Unwinding. The experimental group receiving OFM consisted of 109 people, and the control group receiving a sham treatment had 31 people, all with non-specific low back pain. For comparison, 101 subjects without back pain were also assessed with the ultrasound to determine a mean Kidney Mobility Score (KMS). The landmarks for measuring the renal mobility were the superior renal pole of the right kidney and the pillar of the right diaphragm, and they subtracted the distance at maximal inspiration (RdI) from that of maximal expiration (RdE). A significant difference was found in the KMS scores of asymptomatic versus symptomatic subjects with low back pain. Pre and post-RD values of the experimental group were significantly different from the control group. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire also demonstrated significant differences in the experimental versus control groups. The results of the study revealed a correlation between decreased renal mobility and non-specific low back pain and showed an improvement in renal mobility and low back pain after an osteopathic manipulation.

In 2016, Navot and Kalichman presented a case study of a 32 year old professional male cyclist with right hip and groin pain after an accident that caused a severe hip contusion and tearing of the tensor fascia latae and the gluteus medius muscles. A few rounds of physical therapy gave him partial relief of his pain in sitting and with cycling, and his hip range of motion only improved slightly. Despite no complaints of pelvic floor dysfunction, he was evaluated for involvement of the pelvic floor musculature and fascia. Pelvic Floor Fascial Mobilization was performed for 2 sessions, and the cyclist’s symptoms resolved completely. This case implied the efficacy of manual fascial release of the pelvic floor to reduce hip and groin pain.

When something seemingly orthopedic in nature does not respond with full resolution of symptoms from traditional physical therapy, the source of the pain may be deeper. Often times, we just need to ask the right questions to uncork the mystery of why a pain is lingering. No matter how skilled we are with our techniques, if we are not reaching the area in need, we are wasting our effort and our patients’ time and money. “Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System” is a course that provides a practitioner with the extra insight and tools to address potential sources of unresolved symptoms of low back, hip, and groin pain.

Tozzi, P., Bongiorno, D., and Vitturini, C. (2012) Low back pain and kidney mobility: local osteopathic fascial manipulation decreases pain perception and improves renal mobility. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 16(3):381-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.02.001

Navot, S and Kalichman, L. (2016). Hip and groin pain in a cyclist resolved after performing a pelvic floor fascial mobilization. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 20(3):604-9. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.04.005

A recent systematic review by Bernard et al (2016) looked at the effects of radiation therapy on the structure and function of the pelvic floor muscles of patients with cancer in the pelvic area. Although surgery and chemotherapy are often used treatment approaches in the management of pelvic cancers, this paper specifically focused on radiation therapy: ‘… is often recommended in the treatment of pelvic cancers. Following radiation therapy, a high prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunctions (urinary incontinence, dyspareunia, and fecal incontinence) is reported. However, changes in pelvic floor muscles after radiation therapy remain unclear. The purpose of this review was to systematically document the effects of radiation therapy on the pelvic floor muscle structure and function in patients with cancer in the pelvic area.’

The paper concluded that ‘…There is some evidence that radiation therapy has detrimental impacts on both pelvic floor muscles' structure and function’ and that ‘A better understanding of muscle damage and dysfunction following radiation therapy treatment will improve pelvic floor rehabilitation and, potentially, prevention of its detrimental impacts.’

The paper concluded that ‘…There is some evidence that radiation therapy has detrimental impacts on both pelvic floor muscles' structure and function’ and that ‘A better understanding of muscle damage and dysfunction following radiation therapy treatment will improve pelvic floor rehabilitation and, potentially, prevention of its detrimental impacts.’

Pelvic floor therapists already working in the field of gynecologic oncology will be all too aware of the impacts clinically and functionally on pelvic cancer survivors’ quality of life. We are in a privileged position to provide an evidence based and solution focused approach to the pelvic health issues that are so often under-recognized, and frankly under-addressed for women undergoing treatment for pelvic cancers.

Whether it is advice on managing anal fissures (skin protection, down-training overactive pelvic floor muscles, achieving good stool consistency, teaching defecatory techniques) or dealing with dyspareunia (dilator or vibrator selection, choosing and using an appropriate lubricant, dealing with the ergonomic or orthopedic challenges that can be a barrier to returning to sexual function and enjoyment), pelvic rehab practitioners are probably the best clinicians for optimizing a return to both pelvic and global health during and after treatment for pelvic cancers.

But one of the biggest barriers we face is lack of awareness – on the part of the patients but also, unfortunately the lack of awareness in the medical and oncology community about the benefits of pelvic rehab. Happily this situation is improving – not only is the evidence base expanding from the researchers, but oncologists are recognizing that pelvic rehab is a key component of regaining quality and not just quantity of life after treatment ends. As Yang reported in his 2012 paper – pelvic floor rehab programs improve pelvic floor function (particularly urinary continence and sexual function) and overall quality of life in gynecologic cancer patients. And perhaps, most heartening of all, was his statement that "Pelvic Floor Rehab Physiotherapy is effective even in gynecologic cancer survivors who need it the most"

You can learn more about pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation for cancer patients by attending "Oncology and the Female Pelvic Floor: Female Reproductive and Gynecologic Cancers" on April 29-30, 2017 in Maywood, IL.

‘Effects of radiation therapy on the structure and function of the pelvic floor muscles of patients with cancer in the pelvic area: a systematic review.’ J Cancer Surviv. 2016 Apr;10(2):351-62. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0481-8. Epub 2015 Aug 28. Bernard, S. et al

‘Effect of a pelvic floor muscle training program on gynecologic cancer survivors with pelvic floor dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial.’ Gynecol Oncol. 2012 Jun;125(3):705-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.045. Epub 2012 Apr 1. Yang EJ, et al

When my almost 4 year old still wets his bed in the middle of the night, my first reaction is frustration; but, I learned that gets us nowhere fast, so now I just roll with the punches. Usually the culprit is my stubborn son’s simple refusal to go the bathroom before bed. When enuresis is secondary to neurogenic disorders or anxiety disorders, caregivers need to have even more patience with children.

Sturm and Cheng (2016) published a review on the management of neurogenic bladder in the pediatric population. Central nervous system (CNS) lesions including cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, and spinal malformations, as well as pelvic tumors or anorectal malformations, can all affect normal lower urinary tract function. Children with neurogenic bladder often have the condition because of a CNS lesion. This can affect the bladder’s ability to store and empty urine, so early intervention is essential and focuses on maximizing bladder function and avoiding injury to the upper or lower urinary tracts. With older children, the goals are urinary continence and independent bladder management.

Sturm and Cheng (2016) published a review on the management of neurogenic bladder in the pediatric population. Central nervous system (CNS) lesions including cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, and spinal malformations, as well as pelvic tumors or anorectal malformations, can all affect normal lower urinary tract function. Children with neurogenic bladder often have the condition because of a CNS lesion. This can affect the bladder’s ability to store and empty urine, so early intervention is essential and focuses on maximizing bladder function and avoiding injury to the upper or lower urinary tracts. With older children, the goals are urinary continence and independent bladder management.

Myelomeningocele surgical prenatal closure has had minimal effect on urinary tract function, and parents are encouraged to monitor urological changes because of the child’s risk for neurogenic bladder. Clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) has reduced the morbidity in patients with neurogenic bladder. Determining which children would benefit from initiation of CIC and when medical or surgical interventions should be implemented remains a challenge. Anticholinergics have proven effective on continence and bladder compliance either orally or, more recently, intravesical administration. Surgically, autologous augmentation using the ileum or colon has shown fatal complications like bowel obstruction and bladder rupture, particularly when bladder neck procedures are performed concurrently. Robotic versus open bladder neck reconstruction has been proving more favorable in recent studies. The authors concluded more research is needed for treatment, and the goals are preservation of the upper and lower urinary tracts, optimizing quality of life (Sturm and Cheng 2016).

Considering a different side of nerves, Salehi et al., (2016) studied the relationship between primary nocturnal enuresis and child anxiety disorders. They studied 180 children with primary nocturnal enuresis (referring to children >5 years old having no urine control 6 continuous months) and 180 healthy controls. A statistically significant difference was found between the two groups regarding the frequency of generalized anxiety disorder as well as panic disorder, school phobia, social and separation anxieties, maternal anxiety history, parental history of primary nocturnal enuresis and body mass index. The authors recommended any children with primary nocturnal enuresis should be assessed and treated for generalized anxiety disorder.

The seriousness of enuresis cannot be underestimated. When the cause is neurogenic, pharmacological or surgical intervention may be warranted and lifelong urologic management is needed, especially for a healthy transition into adulthood. As common as nocturnal bed wetting may be in school aged children, they should be monitored for the presence of any anxiety disorders that may be contributing to the disorder. Changing sheets may feel like a burden for parents, but the child with enuresis has a far greater weight to bear.

You can learn all about caring for pediatric patients by attending Pediatric Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction with Dawn Sandalcidi, available twice in 2017.

Sturm, R. M., & Cheng, E. Y. (2016). The Management of the Pediatric Neurogenic Bladder. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports, 11, 225–233. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11884-016-0371-6

Salehi, B., Yousefichaijan, P., Rafeei, M., & Mostajeran, M. (2016). The Relationship Between Child Anxiety Related Disorders and Primary Nocturnal Enuresis. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 10(2), e4462. http://doi.org/10.17795/ijpbs-4462