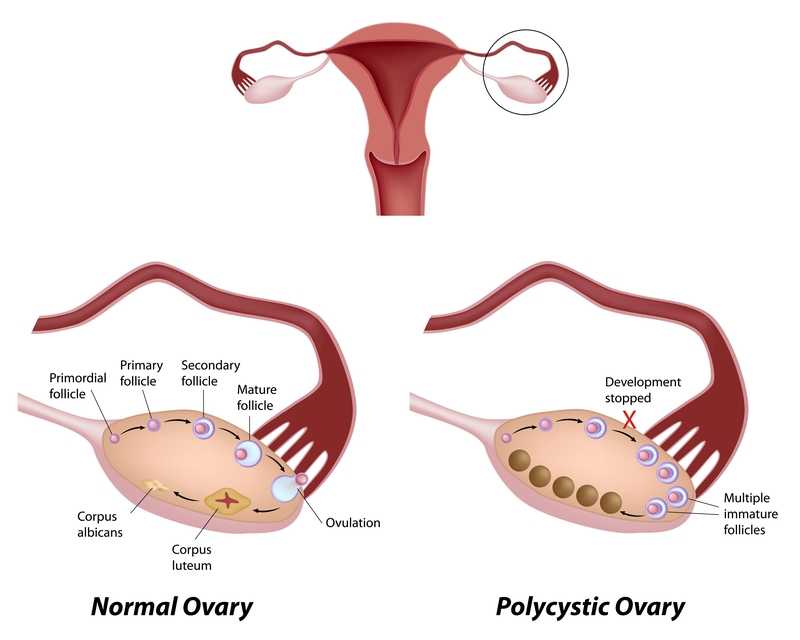

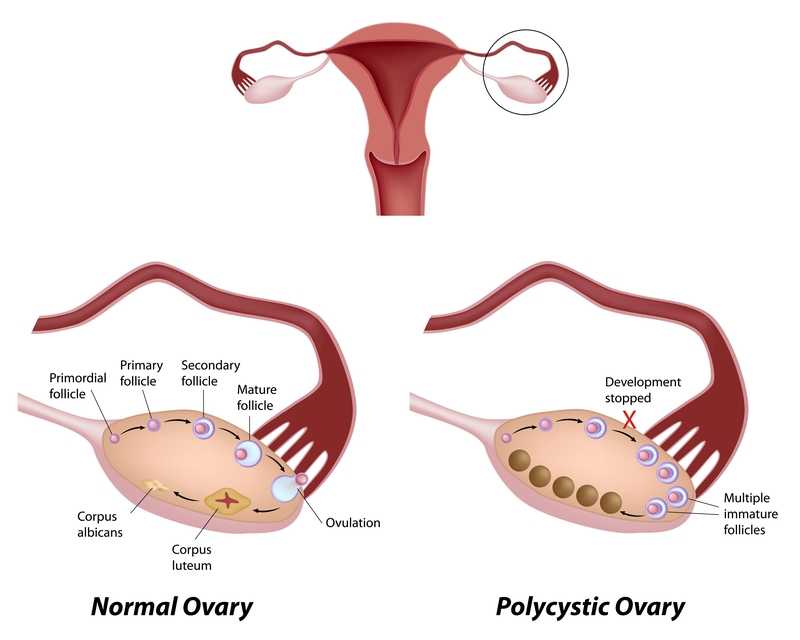

Polycystic ovarian disease (PCOS), also known as Stein-Leventhal syndrome, is an endocrine system disorder that affects women of reproductive age. The disease is associated with some major adverse health issues including infertility, diabetes, metabolic syndrome (a cluster of conditions that increase risk for heart disease, stroke and diabetes), cardiovascular issues and endometrial carcinoma. Because, according to Okamura et al., those with PCOS share risk factors for endometrial cancer and atypical endometrial hyperplasia, early detection and treatment are critical for optimal health outcomes. Some of the primary shared risk factors include obesity, not bearing any children (nulliparity), infertility, hypertension, diabetes, chronic anovulation, and unopposed estrogen supplementation.

One study (Malcolm2017) that addressed reproductive health comparisons among young women with and without PCOS found that although women diagnosed with PCOS had significant concerns about their reproductive health, they were found to be as sexually active as young women without PCOS. Unfortunately, women with PCOS were more likely to have pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which could increase the risk of infertility. In this study, the importance of counseling in safe sex practices such as condom use and sexually transmitted infection screening was highlighted.

As weight loss in women diagnosed with PCOS has been shown to improve blood sugar levels, exercise and healthy weight management strategies can also be keystones of care. Vasheghani-Farahani et al report on a home-based exercise program with positive outcomes in health for women with PCOS. The women in this study were ages 15-40, with 16 patients in the exercise group and 14 in the control group. Blood pressure, waist to hip ratio, BMI, blood tests for insulin factors, sex hormones, and markers of inflammation made up outcomes measures at baseline and again at 12 weeks following intervention. The active group completed aerobic and strengthening exercises and were found to have an improved waist to hip ratio as well as reductions in cardiovascular risk profiles.

The exercise instructed as home program is as follows: 30 minute walk at least 5 days per week at medium intensity (64%-76% max heart rate), strengthening exercises of biceps curl, wall push up, chair push up, single arm row, seated lower leg lift, seated straight leg lift, stair step and chair squat 10 times each. The participants were instructed to increase the exercise bouts per day from 1 to 3 by the end of the study. Participants were guided through the exercises at the beginning of the study, and exercise logs as well as phone calls were used to track progress, answer questions.

This study is an encouraging example of simple yet effective strategies to guide women diagnosed with PCOS. Although there are other equally valuable aspects of care that a pelvic health therapist can be involved in for women managing this challenging disease, the research presented reminds us that basic information on healthy sexual practices and provider follow-up, strengthening and aerobic exercise can have meaningful impact on quality of life. If you are interested in learning more about PCOS and other endocrine conditions, and ways to help manage pelvic pain, adhesions, and other symptoms, join us in Pelvic Floor Series Capstone: Advanced Topics in Pelvic Rehab, available twice more in 2017.

Malcolm, S., Tuchman, L., Cheng, Y. I., Wang, J., & Gomez-Lobo, V. (2017). Differences in Reproductive Health Issues in Adolescent Females With Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Compared to Controls. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 30(2), 330-331.

Okamura, Y., Saito, F., Takaishi, K., Motohara, T., Honda, R., Ohba, T., & Katabuchi, H. (2017). Polycystic ovary syndrome: early diagnosis and intervention are necessary for fertility preservation in young women with endometrial cancer under 35 years of age. Reproductive Medicine and Biology, 16(1), 67-71.

Vasheghani-Farahani, F., Khosravi, S., Yekta, A. H. A., Rostami, M., & Mansournia, M. A. (2017). The Effect of Home based Exercise on Treatment of Women with Poly Cystic Ovary Syndrome; a single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Novelty in Biomedicine, 5(1), 8-15.

At a hair salon, I once saw a plaque that declared, “I’m a beautician, not a magician.” This crossed my mind while reading research on radical prostatectomy, as knowing the baseline penile function of men before surgery seemed challenging. Restoring something that may have been subpar prior to surgery can be a daunting task, and it can cause discrepancies in results of clinical trials. Despite this, two recent studies reviewed the current and future penile rehabilitation approaches post-radical prostatectomy.

Bratu et al.2017 published a review referring to post-radical prostatectomy (RP) erectile dysfunction (ED) as a challenge for patients as well as physicians. They emphasized the use of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) Questionnaire to establish a man’s baseline erectile function, which can be affected by factors such as age, diabetes, alcohol use, smoking habits, heart and kidney diseases, and neurological disorders. The higher the IIEF score preoperatively, the higher the probability of recovering erectile function post-surgery. The experience of the surgeon and the technique used were also factors involved in ED. Radical prostatectomy is a trauma to the pelvis that negatively affects oxygenation of the corpora cavernosum, resulting in apoptosis and fibrotic changes in the tissue, leading to ED. Minimally invasive surgery allows a significantly lower rate of post-RP ED with robot assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) versus open surgery. The cavernous neurovascular bundles get hypoxic and ischemic regardless of the technique used; therefore, the authors emphasized early post-op penile rehabilitation to prevent fibrosis of smooth muscle and to improve cavernous oxygenation for the potential return of satisfactory sexual function within 12-24 months.

Clavell-Hernandez and Wang2017 [and Bratu et al., (2017)] reported on various aspects of penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy. The treatment with the most research to support its efficacy and safety was oral phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors (PDE5Is), which help relax smooth muscle and promote erection on a cellular level. Sildenafil, vardenafil, avanafil, and tadalafil have been studied, either used on demand or nightly. Tadalafil had the longer half-life and was considered to have the greatest efficacy. Nightly versus on-demand for any PDE5I was variable in its results. Intracavernosal injection (ICI) and intraurethral therapy using alprostadil for vasodilation improved erectile function, but it caused urethral burning and penile pain. Vacuum erection devices (VED) promoted penile erection via negative pressure around the penis, bringing blood into the corpus cavernosum. There was no need for intact corporal nerve or nitric oxide pathways for proper function, and it allowed for multiple erections in a day. Intracavernous stem cell injections provided a promising approach for ED, and they may be combined with PDE5Is or low-energy shockwave therapy. Ultimately, the authors concluded early penile rehabilitation should involve a combination of available therapies.

Restoring vascularity to healing tissue is a primary goal in rehabilitation, and the sooner the better. Disruption of cavernous nerves and penile tissue post-RP demands rehabilitation, and some methods have more supporting clinical evidence than others. Newer approaches require more exposure and clinical trials for efficacy and long term outcomes. Clinicians should pay attention to updated research and consider taking continuing education courses such as Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation or Oncology and the Male Pelvic Floor.

Bratu, O., Oprea, I., Marcu, D., Spinu, D., Niculae, A., Geavlete, B., & Mischianu, D. (2017). Erectile dysfunction post-radical prostatectomy – a challenge for both patient and physician. Journal of Medicine and Life, 10(1), 13–18.

Clavell-Hernández, J., & Wang, R. (2017). The controversy surrounding penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy. Translational Andrology and Urology, 6(1), 2–11. http://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2016.08.14

Speaking with a runner friend the other day, I mentioned I was writing a blog on yoga for pelvic pain. She had the same reaction many runners do, stating she has doesn’t care for yoga, she never feels like she is tight, and she would hate being in one position for so long. Ironically, neither of us has taken a yoga class, so any preconceived ideas about it are null and void. I told her yoga is being researched for beneficial health effects, and one day we just might find ourselves in a class together!

Saxena et al.2017 published a study on the effects of yoga on pain and quality of life in women with chronic pelvic pain. The randomized case controlled study involved 60 female patients, ages 18-45, who presented with chronic pelvic pain. They were randomly divided into two groups of 30 women. Group I received 8 weeks of treatment only with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDS). Group II received 1 hour, 5 days per week, for 8 weeks of yoga therapy (asanas, pranayama, and relaxation) in addition to NSAIDS (as needed). Table 1 in the article outlines the exact protocol of yoga in which Group II participated. The subjects were assessed pre- and post-treatment with pain scores via visual analog scale score and quality of life with the World Health Organization quality of life-BREF questionnaire. In the final analysis, Group II showed a statistically significant positive difference pre and post treatment as well as in comparison to Group I in both categories. The authors concluded yoga to be an effective adjunct therapy for patients with chronic pelvic pain and an effective option over NSAIDS for pain.

Saxena et al.2017 published a study on the effects of yoga on pain and quality of life in women with chronic pelvic pain. The randomized case controlled study involved 60 female patients, ages 18-45, who presented with chronic pelvic pain. They were randomly divided into two groups of 30 women. Group I received 8 weeks of treatment only with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDS). Group II received 1 hour, 5 days per week, for 8 weeks of yoga therapy (asanas, pranayama, and relaxation) in addition to NSAIDS (as needed). Table 1 in the article outlines the exact protocol of yoga in which Group II participated. The subjects were assessed pre- and post-treatment with pain scores via visual analog scale score and quality of life with the World Health Organization quality of life-BREF questionnaire. In the final analysis, Group II showed a statistically significant positive difference pre and post treatment as well as in comparison to Group I in both categories. The authors concluded yoga to be an effective adjunct therapy for patients with chronic pelvic pain and an effective option over NSAIDS for pain.

In the Pain Medicine journal, Huang et al.2017 presented a single-arm trial attempting to study the effects of a group-based therapeutic yoga program for women with chronic pelvic pain (CPP), focusing on severity of pain, sexual function, and overall well-being. The comprehensive program was created by a group of women’s health researchers, gynecological and obstetrical medical practitioners, yoga consultants, and integrative medicine clinicians. Sixteen women with severe pelvic pain of at least 6 months’ duration were recruited. The group yoga classes focused on lyengar-based techniques, and the subjects participated in group classes twice a week and home practice 1 hour per week for 6 weeks. The Impact of Pelvic Pain (IPP) questionnaire assessed how the participants’ pain affected their daily life activities, emotional well-being, and sexual function. Sexual Health Outcomes in Women Questionairre (SHOW-Q) offered insight to sexual function. Daily logs recorded the women’s self-rated pelvic pain severity. The results showed the average pain severity improved 32% after the 6 weeks, and IPP scores improved for daily living (from 1.8 to 0.9), emotional well-being (from 1.7 to 0.9), and sexual function (from 1.9 to 1.0). The SHOW-Q "pelvic problem interference" scale also improved from 53 to 23. The multidisciplinary panel concluded they found preliminary evidence that teaching yoga to women with CPP is feasible for pain management and improvement of quality of life and sexual function.

Whatever treatment we provide for our patients, we need to consider the individual and their often biased opinions or perceptions. Providing research and educating each patient on the efficacy behind the proposed therapy will likely impact their outcome. The Yoga for Pelvic Pain course can enhance a clinician’s understanding and allow them to better implement a potentially life-changing therapy for their clients.

Saxena, R., Gupta, M., Shankar, N., Jain, S., & Saxena, A. (2017). Effects of yogic intervention on pain scores and quality of life in females with chronic pelvic pain. International Journal of Yoga, 10(1), 9–15. http://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.186155

Huang, AJ, Rowen, TS, Abercrombie, P, Subak, LL, Schembri, M, Plaut, T, & Chao, MT. (2017). Development and Feasibility of a Group-Based Therapeutic Yoga Program for Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Pain Medicine. http://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw306

What if we were only taught treatment techniques during our healthcare training with no theory or explanation as to why or on whom or under what circumstances they should be used? Focusing on “how to” but ignoring the “discernment as to why” would make for a weak clinician. Manual therapy for the pelvic floor is a treatment approach to implement once we have used our heads and palpation skills to reveal the underlying source of dysfunction.

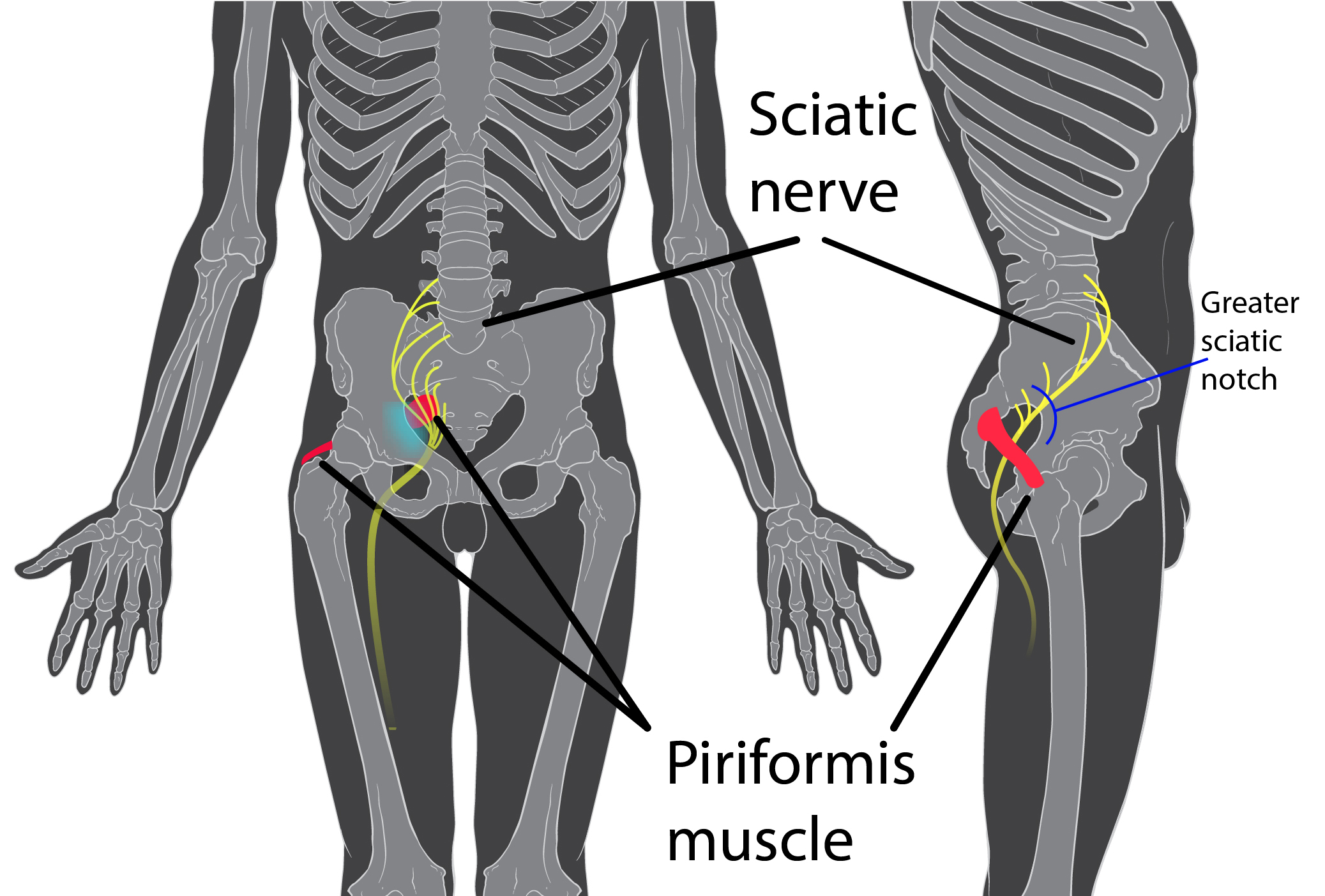

Pastore and Katzman (2012) published a thorough article describing the process of recognizing when myofascial pain is the source of chronic pelvic pain in females. They discuss active versus latent myofascial trigger points (MTrPs), which are painful nodules or lumps in muscle tissue, with the latter only being symptomatic when triggered by physical (compression or stretching) or emotional stress. Hyperalgesia and allodynia are generally present in patients with MTrPs, and muscles with MTrPs are weaker and limit range of motion in surrounding joints. In pelvic floor muscles, MTrPs refer pain to the perineum, vagina, urethra, and rectum but also the abdomen, back, thorax, hip/buttocks, and lower leg. The authors suggest detecting a trigger point by palpating perpendicular to the muscle fiber to sense a taut band and tender nodule and advise using the finger pads with a flat approach in the abdomen, pelvis and perineum. They emphasize a multidisciplinary approach to finding and treating MTrPs and making sure urological, gynecological, and/or colorectal pathologies are addressed. A thorough subjective and physical exam that leads to proper diagnosis of MTrPs should be followed by manual physical therapy techniques and appropriate medical intervention for any corresponding pathology.

Halder et al. (2017) investigated the efficacy of myofascial release physical therapy with the addition of Botox in a retrospective case series for women with myofascial pelvic pain. Fifty of the 160 women who had Botox and physical therapy met the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the primary complaint in all those subjects was dyspareunia. The Botox was administered under general anesthesia, and then the same physician performed soft tissue myofascial release transvaginally for 10-15 minutes, with 10-15 additional minutes performed if rectus muscles had trigger points. The patients were seen 2 weeks and 8 weeks posttreatment. Average pelvic pain scores decreased significantly pre- and posttreatment, with 58% of subjects reporting improvements. Significantly fewer patients (44% versus 100%) presented with trigger points on pelvic exam after the treatment. The patients who did not show improvement tended to have inflammatory or irritable bowel diseases or diverticulosis. Blocking acetylcholine receptors via Botox in combination with pelvic floor physical therapy could possibly provide longer symptom-free periods. Although the nature of the study could not determine a specific interval of relief, the authors were encouraged as an average of 15 months passed before 5 of the patients sought more treatment.

The need for the specific treatment for myofascial pelvic pain is determined by a clinician competent in palpation of the pelvic floor musculature finding trigger points and restrictions in the tissue. Listening to a patient’s symptoms and understanding pelvic pathology allow for better treatment planning. Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist is a comprehensive course to enhance knowledge in your head to lead your hands in the right direction for assessing/treating patients with pelvic pain.

Pastore, E. A., & Katzman, W. B. (2012). Recognizing Myofascial Pelvic Pain in the Female Patient with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing : JOGNN / NAACOG, 41(5), 680–691. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01404.x

Halder, G. E., Scott, L., Wyman, A., Mora, N., Miladinovic, B., Bassaly, R., & Hoyte, L. (2017). Botox combined with myofascial release physical therapy as a treatment for myofascial pelvic pain. Investigative and Clinical Urology, 58(2), 134–139. http://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2017.58.2.134

While running on my treadmill, I watched a commercial advertising specially designed pads as “the solution” for women athletes who “leak” during their sport. Before my introduction to Herman and Wallace Rehabilitation Institute, I would have rushed to the nearest store to buy a case of them. When we don’t know how to fix a problem, we tend to cling to bandages to cover them, allowing us to ignore them. With 29 years of running and racing and 2 natural childbirths under my belt, leaks have happened, and it is common. However, leaks due to urinary stress incontinence are not normal and do not stop simply because you place a contoured, sporty, sanitary pad in the lining of your shorts.

A 2016 cross-sectional study by Ameida et al. investigated urinary incontinence (UI) and pelvic floor dysfunctions (PFD) such as constipation, anal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, vaginal laxity, and dyspareunia in female athletes who participate in high-impact sports. The 67 amateur athletes and 96 non-athletes completed an ad hoc survey to determine PFD symptoms. Artistic gymnasts, trampolinists, swimmers, and judo participants were among the athletes with the highest risk of urinary incontinence. Although the athletes had a higher risk of UI, they reported less constipation, less straining to relieve themselves, and less manual assistance for defecation than the non-athletes. The authors were able to conclude that high impact sports or sports requiring a strong effort put athletes at risk for UI, uncontrolled gas expulsion, and even sexual dysfunction. They emphasize a need for attention to be given to pelvic floor training for rehabilitation as well as preventative strategies and education for high risk yet asymptomatic athletes.

A 2016 cross-sectional study by Ameida et al. investigated urinary incontinence (UI) and pelvic floor dysfunctions (PFD) such as constipation, anal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, vaginal laxity, and dyspareunia in female athletes who participate in high-impact sports. The 67 amateur athletes and 96 non-athletes completed an ad hoc survey to determine PFD symptoms. Artistic gymnasts, trampolinists, swimmers, and judo participants were among the athletes with the highest risk of urinary incontinence. Although the athletes had a higher risk of UI, they reported less constipation, less straining to relieve themselves, and less manual assistance for defecation than the non-athletes. The authors were able to conclude that high impact sports or sports requiring a strong effort put athletes at risk for UI, uncontrolled gas expulsion, and even sexual dysfunction. They emphasize a need for attention to be given to pelvic floor training for rehabilitation as well as preventative strategies and education for high risk yet asymptomatic athletes.

In 2015, DaRoza et al. performed a cross-sectional cohort study to determine the urinary leakage in 22 young female trampolinists based on the volume of their training and level of ranking. Leakage was assessed by the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Short-Form (ICIQ-UI-SF), and another questionnaire determined each athlete’s championship ranking and training volume. An astounding 72.7% of girls reported urine leakage since starting to perform on the trampoline, and the greatest severity was significantly associated with the highest training volume. The impact of UI on the athlete’s quality of life was greatest in this 3rd tertile. The authors recommended these athletes with a high frequency of UI be educated on the impact of their sport on their pelvic floor muscles and proposed they get treated by pelvic health professionals to minimize or resolve the incontinence.

Thankfully, none of the above researchers or medical professionals advises the study participants to just use a pad and carry on with their sport. Urinary incontinence is a real problem in athletes, and its prevalence is appalling. Even young girls without any birthing of babies to blame are leaking. Making females (and males) aware of the impact sports can have on their pelvic floor and educating them that urinary leakage is not normal are essential missions for healthcare professionals. “The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor” course can help integrate pivotal aspects of pelvic rehabilitation into sports medicine, as some conditions just may require training to move down to the pelvic floor for complete recovery.

Almeida, MB, Barra, AA, Saltiel, F, Silva-Filho, AL, Fonseca, AM, Figueiredo, EM. (2016). Urinary incontinence and other pelvic floor dysfunctions in female athletes in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 26(9):1109-16. http://doi:10.1111/sms.12546

Da Roza, T, Brandão, S, Mascarenhas, T, Jorge, RN, Duarte JA. (2015). Volume of training and the ranking level are associated with the leakage of urine in young female trampolinists. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 25(3):270-5. http://DOI:10.1097/JSM.0000000000000129

While recently visiting Seattle with my daughter, we had the pleasure of talking with Dr. Ghislaine Robert, owner of Sparclaine Regenerative Medicine. She is a highly respected sports medicine doctor who has steered much of her practice towards regenerative medicine, with a focus on stem cell and platelet enriched plasma (PRP) injections. She brought to my attention the use of stem cells for pelvic floor disorders. And, like any successful practitioner, she encouraged me to research it for myself.

In 2015, Cestaro et al. reported early results of 3 patients with fecal incontinence receiving intersphincteric anal groove injections of fat tissue. They aspirated about 150ml of the fat tissue and used the Lipogem system technology lipofilling technique to provide micro-fragmented and transplantable clusters of lipoaspirate. The intersphincteric space was then injected with the lipoaspirate. A proctology exam was performed at 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months following the procedure. All 3 patients all had reduced Wexner incontinence scores 1 month post-treatment and a significant improvement in quality of life 6 months post-procedure. Resting pressure of the internal anal sphincter increased after 6 months, and the internal anal sphincter showed increased thickness.

A 2016 study by Mazzanti et al., used rats to explore whether unexpanded bone marrow-derived mononuclear mesynchymal cells (MNC) could effectively repair anal sphincter healing since expanded ones (MSC) had already been shown to enhance healing after injury in a rat model. They divided 32 rats into 4 groups: sphincterotomy and repair (SR) with primary suture of anal sphincters and a saline intrasphincteric injection (CTR); SR of anal sphincter with in-vitro expanded MSC; SR of anal sphincter with minimally manipulated MNC; and, a sham operation with saline injection. Muscle regeneration as well as contractile function was observed in the MSC and MNC groups, while the control surgical group demonstrated development of scar tissue, inflammatory cells and mast cells between the ends of the interrupted muscle layer 30 days post-surgery. Ultimately, the authors found no significant difference between expanded or unexpanded bone marrow stem cell types used. Post-sphincter repair can be enhanced by stem cell therapy for anal incontinence, even when the cells are minimally manipulated.

Finally, in 2017, Sarveazad et al. performed a double-blind clinical trial in humans using human adipose-derived stromal/stem cells (hADSCs) from adipose tissue for fecal incontinence. The hADSCs secrete growth factor and can potentially differentiate into muscle cells, which make them worth testing for improvement of anal sphincter incontinence. They used 18 subjects with sphincter defects, 9 undergoing sphincter repair with injection of hADSCs and 9 having surgery with a phosphate buffer saline injection. After 2 months, there was a 7.91% increase in the muscle mass in the area of the lesion for the cell group compared to the control. Fibrous tissue replacement with muscle tissue, allowing contractile function, may be a key in the long term for treatment of fecal incontinence.

As long as accessing human-derived stem cells is a viable option for patients, the preliminary studies show promise for success. With fecal incontinence being such a debilitating problem for people, especially socially, stem cells are definitely an up and coming treatment, and we should all keep up on this research. After all, who wouldn’t spare some adipose tissue for life-changing, functional gains?

Cestaro, G., De Rosa, M., Massa, S., Amato, B., & Gentile, M. (2015). Intersphincteric anal lipofilling with micro-fragmented fat tissue for the treatment of faecal incontinence: preliminary results of three patients. Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques, 10(2), 337–341. http://doi.org/10.5114/wiitm.2014.47435

Mazzanti, B., Lorenzi, B., Borghini, A., Boieri, M., Ballerini, L., Saccardi, R., … Pessina, F. (2016). Local injection of bone marrow progenitor cells for the treatment of anal sphincter injury: in-vitro expanded versus minimally-manipulated cells. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 7, 85. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-016-0344-x

Sarveazad, A., Newstead, G. L., Mirzaei, R., Joghataei, M. T., Bakhtiari, M., Babahajian, A., & Mahjoubi, B. (2017). A new method for treating fecal incontinence by implanting stem cells derived from human adipose tissue: preliminary findings of a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 8, 40. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-017-0489-2

The Center for Disease Control reports that prostate cancer is the most common form of male cancer in the United States (just ahead of lung cancer and colorectal cancer), and the American Cancer Society estimates that 1 in 7 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point in their lifetime. With prostate cancer being so common, it is likely that a male with symptoms of urinary incontinence following a prostatectomy may show up at your clinic’s door for treatment. What do you do? Whether you have extensive training for male pelvic floor disorders or are just starting your initial training for pelvic floor dysfunctions, you likely have some intervention skills to help this population.

A recent case report in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, outlines management of a 76-year-old male patient with mixed urinary incontinence postprostatectomy 10 years. This case report does a nice job describing not just physical therapy (PT) interventions, but also multifaceted management of a typical patient post radical prostatectomy. The case report describes a thorough history, systems review, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) examination, tests &measures, and outcome assessment. Our discussion will focus on interventions as you may already possess the skills for several of the treatments included in this patient’s plan of care.

A recent case report in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, outlines management of a 76-year-old male patient with mixed urinary incontinence postprostatectomy 10 years. This case report does a nice job describing not just physical therapy (PT) interventions, but also multifaceted management of a typical patient post radical prostatectomy. The case report describes a thorough history, systems review, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) examination, tests &measures, and outcome assessment. Our discussion will focus on interventions as you may already possess the skills for several of the treatments included in this patient’s plan of care.

The patient’s complaints were mixed urinary incontinence (UI) symptoms including 3-4 pads per day and 1 pad at night. He reported nocturia 3-4 times per night. 2-3 times per week he had large UI episodes that soaked his outwear. Also, he complained of inability to delay voiding, and UI with walking to the bathroom, sit to stand, lifting, coughing, and sneezing.

For the patients’ urge UI symptoms, behavioral interventions were utilized. The patient completed PFM contractions to inhibit detrusor contractions and suppress urgency (urge control technique). Educating the patient on correct PFM contraction isolation was a very important component of this patients’ treatment. Verbal, digital, and surface electromyography (sEMG) techniques were used to ensure correct PFM contraction and to reduce Valsalva. Clinical decision making for home exercise program utilized dominant PFM fiber types and the patients’ performance on the PERFECT PFM strength testing system described by Laycock. (External Urethral Sphincter is predominantly Type II fast twitch muscle fiber in males and Levator Ani is predominantly Type I slow twitch.) For the home program, the patient completed progressive reps and sets of 10” (targets slow twitch) and 2” (targets fast twitch) PFM isometrics in supine progressing to standing. (There is a chart with additional details on PFM home program for each visit in the case report.) Additionally, instruct and use of “the knack” (volitional PFM contraction before and during cough or other physical exertions to prevent UI) for activities that the patient usually had UI with including sit to stand transfer, lifting, coughing, and sneezing was essential for the patients’ symptoms. PFM coordination training with sEMG helped reduce his accessory muscle recruitment patterns and Valsalva. Bladder retraining and lifestyle recommendation were important (per his 3-day bladder diary) as he was consuming 3 cups of coffee and 4 cups or more of tea a day, likely contributing to urgency and urge UI symptoms. Also, he was informed regarding the effect of obesity on UI (as his BMI was 35.9 placing him in the obese range) and that modest amounts of weight loss maybe sufficient for UI reduction. Abdominal exercises targeting Transversus Abdominus were also prescribed for their role in core support with PFM’s. Lastly, electrical stimulation was not included in this patients’ plan of care due to the patients’ cardiac history and pacemaker, as well as, he could initiate PFM contraction and utilize urge control techniques appropriately.

The outcome for this patient was positive. He attended 5 PT sessions over a 3-month period. He did have to cancel two appointments between the 4th and 5th visits due to an emergency surgery to place two cardiac stents. He had reduced urinary leakage indicated by reduced undergarment changes and reduced pad usage per day. His pads were less saturated and he no longer had leakage that spread to his outwear. He had a 50% reduction in UI episodes reported on his bladder diary and a 50% reduction in nocturia from 4 times to 2 times per night. He reported reduced daily urinary frequency from 7 to 5 times per day with no instances of severe urgency. He demonstrated improved PERFECT score of 4, 10, 8, 10 (initially his score was 2, 5, 3, 5) indicating improved PFM strength and endurance. Also, he had improved PFM coordination as he could isolate PFM contraction without Valsalva or accessory muscle activation. He also had one strength grade improvement with abdominal strength. All that being said, most importantly, this patient had improved rating on the outcome questionnaire (International Continence Society male Short Form (ICSmaleSF)) at discharge indicating improved quality of life. At initial evaluation, this patient rated “a lot” (3 on ICSmaleSF) when asked how much the urinary symptoms interfered with his life, at discharge he reported “not at all” (0 on ICSmaleSF).

One component to this case that I found fascinating was the duration of time that had passed since this patients’ prostatectomy. It had been 10 years since this patient had his surgical procedures. He had never been offered physical therapy or knew about it as a possible treatment for his symptoms. Additionally, that he could have such success with improvements in voiding and incontinence function, as well as improved quality of life as long as 10 years’ post-prostatectomy.

This case report is a comprehensive glimpse of what physical therapy assessment and treatment may look like for a patient with urinary dysfunction following radical prostatectomy. This patient had great improvements with positive changes enhancing his quality of life. So, if you are considering adding treatment of this population to your practice consider attending Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation, available this July in Annapolis, MD or September in Seattle, WA.

"Cancer Among Men", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Roscow, A. S., & Borello-France, D. (2016). Treatment of Male Urinary Incontinence Post–Radical Prostatectomy Using Physical Therapy Interventions. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 40(3), 129-138.

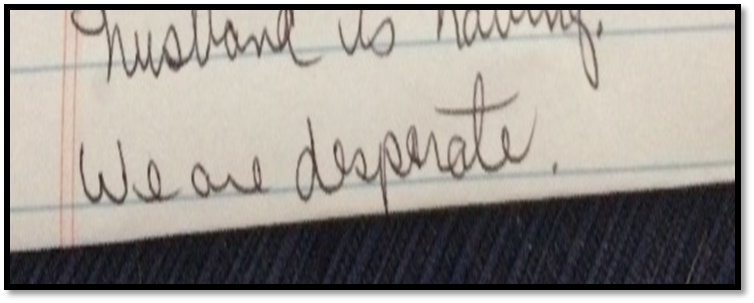

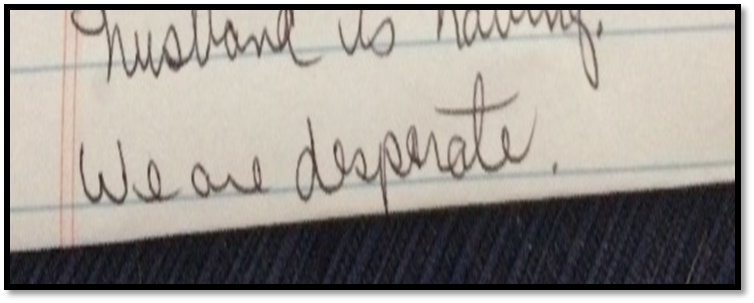

Male Pelvic Pain: What Therapists Can Do to Help End the Desperation

Recently, a note was left at my doorstep by the wife of an older gentleman who had chronic male pelvic pain. His pain was so severe, he could not sit, and he lay in the back seat of their idling car as his wife, having exhausted all other medical channels available to her, walked this note up to the home of a rumored pelvic floor physical therapist who also treated men. The note opened with how she had heard of me. She then asked me to contact her about her husband’s medical problem. It ended with three words that have vexed me ever since…we are desperate.

Unlike so many men with chronic pelvic pain, he had at least been given a diagnostic cause of his pain, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, rather than vaguely being told it was just a prostate issue. However, the therapists that had been recommended by his doctor only treated female pelvic dysfunction.

“We are desperate”: A Call to Action for All Therapists to become Pelvic Floor Inclusive

My first thought after reading the note was, “I bet shoulder or knee therapists don’t get notes like this on their doorstep.” My next thought, complete with facepalm, “THIS HAS TO STOP! Pelvic floor rehab has got to become more accessible”.

Pelvic floor therapists see men and women and even transgenders. They treat in the pediatric, adult, and geriatric population. They treat pelvic floor disorders in the outpatient, home health and SNF settings. They treat elite athletes and those with multiple co-morbidities using walkers. They can develop preventative pelvic wellness programs and teach caregivers how to better manage their loved one’s incontinence. This is due to one simple fact: No matter the age, gender, level of health or practice setting, every patient has a pelvic floor.

The pelvic floor should not be regarded as some rare zebra in clinical practice when it is the workhorse upon which so many health conditions ride. It interacts with the spine, the hip, the diaphragm, and vital organs. It is composed of skin, nerves, muscles, tendons, bones, ligaments, lymph glands, and vessels. It is as complex and as vital to function and health as the shoulder or knee is, and yet students are lucky if they get a “pelvic floor day” in their PT or OT school coursework.

I call for every therapist, specialist, and educator to learn more about the pelvic floor. Here are some steps you can take today toward eliminating the need for such a note to be written.

If you are a pelvic floor therapist who treats men, shout it from the rooftops!

Contact every PT clinic, every SNF, every doctor, every nurse, every chiropractor, every acupuncturist, every massage therapist, every personal trainer, every community group and let them know! If you have already told them, tell them again. Send a one page case study with your business card. Host a free community health lecture at the library or VFW hall. Keep the conversation going. Reach out to your local rehab or nursing school programs and volunteer to speak to the students. Feature pelvic health topics in your clinic’s social media stream. Get on every single therapist locator that you can so people can find you. Click here to go to the Herman and Wallace Find a Practitioner site.

If you only treat pelvic dysfunction in women, please consider expanding your specialty to include men.

The guys really need your help. You literally may be the only practitioner around that has the skills to treat these types of problems. Yes, the concerns you have about privacy and feeling comfortable are valid. But, you are not alone in this. Smart people like Holly Tanner have figured all that stuff out for you and can guide you on how to expertly treat in the men’s health arena. Sign up for Male Pelvic Floor or take an introductory course online at Medbridge. If you have only taken PF1, it’s time to sign up for Pelvic Floor Level 2A: Function, Dysfunction and Treatment: Colorectal and Coccyx Conditions, Male Pelvic Floor, Pudendal Nerve Dysfunction. Reach out to other pelvic floor therapists that treat men and ask for mentorship.

If you are general population therapist, consider taking a pelvic floor course.

Good news! Not every pelvic floor course requires you to glove up and donate your pelvis to science, so to speak. Yes, there are several external only courses you can take that do not have an internal examination lab. Click here and look under “course format” to see a list of external only courses. If you treat in the outpatient, ortho, or sports medicine arena, consider taking Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis: Manual Movement Therapy and the Myofascial Sling System or the Athlete and the Pelvic Floor .

If you treat in the Medicare age population, work in skilled nursing, or home health, join me in New York on May 21-22 for Geriatric Pelvic Floor. It is an external course and we cover documentation and self-care strategies extensively for incontinence and pelvic pain in older adults across multiple settings. Older adults with pelvic pain, like the man in the back seat, are at risk for being diagnostically ignored. We will address biases, such as “prostato-centric” thinking, ageism, and the ever-present “no fracture no problem” prognosis given to seniors who sustain a fall, but are left with disabling soft tissue dysfunction.

If you are a PT or OT school educator, eliminate “Pelvic Floor Day”.

Sorry, but it sounds silly. It’s like saying you offer a “Knee Day” in your program. Replace it by including the pelvic floor into Every. Single. Class…anatomy, ther ex, neuro, peds, geriatrics, and even cardiopulmonary!

As the baby boomer population grows, pelvic floor disorders are expected to rise significantly (download a free white paper on pelvic floor trends here). Are you preparing your doctorate students to be competent screeners of pelvic floor dysfunction? Pelvic floor rehab is becoming the gold standard of first line treatments for pelvic dysfunction. Are you giving your students the skills to be competitive in a job market that recognizes pelvic floor rehabilitation as standard of care? Bias is learned. Excluding the pelvic floor in your student’s coursework or presenting it as a niche specialty subtly reinforces this bias.

Reach out and ask your local pelvic floor therapists to guest lecturer throughout the program. Send your instructors to pelvic floor courses. Encourage your students to take Pelvic Floor Level 1 in their last 6 months of coursework. Offer a clinical rotation in pelvic floor rehabilitation. Include case studies and patient perspectives on pelvic dysfunction, such as A Patient’s Pelvic Rehab Journey.

The Silver Lining

Thanks to the champions of pelvic floor rehab education, we’ve come a long way. The good news in this story is that this man’s doctor recognized early that he had pelvic floor muscle dysfunction and recommended that he see a pelvic floor physical therapist. The bad news-it took 2 years before he could find one. The ball is in our court, therapists. Let’s do better. Until there are no more men in the back seat, we still need to #LearnMoreAboutThePelvicFloor.

After my Dad’s 3rd trip to the emergency room not being able to breathe because of his sleep apnea and congestive heart failure, his cardiologist recommended he ”just relax” when his suffocating feelings occurred. Of course, not being able to catch his breath would always heighten anxiety, which made it even more difficult to inhale and exhale. Ultimately, what my Dad needed to learn was mindfulness to deal with his relatively benign inability to breathe, since the focus of mindfulness is acceptance of rather than control over your circumstances.

The concept of mindfulness has been studied in adults, but it is gaining popularity among the pediatric population. Ruskin et al., (2017) used a prospective pre-post interventional study to assess how children with chronic pain respond to mindfulness-based interventions (MBI’s). For 8 weeks, 21 adolescents engaged in group sessions of MBI. Before, after, and 3 months post-treatment, the authors collected self-report measurements for a variety of factors such as disability, anxiety, pain quality, acceptance, catastrophizing, and social support. Subjects were highly satisfied with the treatment, and all would recommend the group intervention to friends. From baseline to 3-month follow-up, pain acceptance, body awareness, and ability to cope with stress all improved in the subjects. Further randomized controlled studies are needed, but the initial conclusion was MBI’s were received well by adolescents.

The concept of mindfulness has been studied in adults, but it is gaining popularity among the pediatric population. Ruskin et al., (2017) used a prospective pre-post interventional study to assess how children with chronic pain respond to mindfulness-based interventions (MBI’s). For 8 weeks, 21 adolescents engaged in group sessions of MBI. Before, after, and 3 months post-treatment, the authors collected self-report measurements for a variety of factors such as disability, anxiety, pain quality, acceptance, catastrophizing, and social support. Subjects were highly satisfied with the treatment, and all would recommend the group intervention to friends. From baseline to 3-month follow-up, pain acceptance, body awareness, and ability to cope with stress all improved in the subjects. Further randomized controlled studies are needed, but the initial conclusion was MBI’s were received well by adolescents.

A feasibility study performed by Anclair, Hjärthag, and Hiltunen in 2017 considered the effect of mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy for the parents of children with chronic conditions, looking at Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL), measured with Short Form-36 (SF-36), and life satisfaction. Ten parents received group-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and 9 participated in a group-based mindfulness program (MF). Treatment was implemented for 2-hour weekly sessions over the course of 8 weeks. The CBT treatment was based on the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, focusing on changing thoughts and emotions about stressful issues as well as behaviors. They avoided the acceptance aspect, as it would overlap the MF intervention. The MF therapy used the Here and Now Version 2.0 (including daily themes on knowing your body, observing breathing, acceptance, meditation, coping, understanding thoughts versus facts, and self-care reinforcement). The parents in each group significantly improved their Mental Component Summary (MCS), Vitality, Social functioning, and Mental health scores. The MF group even showed notable improvement in Role emotional and some of the physical subscales (Bodily pain, General health, and Role physical). The CBT group showed improved satisfaction with Spare time and Relation to partner, and CBT and MF groups improved life satisfaction Relation to child. The authors conclude CBT and MF may positively affect HRQOL and life satisfaction of parents with chronically ill children.

Whether young or old or in between, how we perceive stressful situations and chronic pain can impact our health. The neurodevelopmental aspect of mindfulness is still being studied. The “Mindfulness Based Pain Treatment” course applies the concept to treating chronic pain patients. This approach brings to mind the Serenity Prayer by Reinhold Niebuhr: “Lord grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Ruskin ,DA, Gagnon, MM, Kohut SA, Stinson JN, Walker KS. (2017). A Mindfulness Program Adapted for Adolescents With Chronic Pain: Feasibility, Acceptability, and Initial Outcomes. The Clinical Journal of Pain. http://www.doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000490

Anclair, M., Hjärthag, F., & Hiltunen, A. J. (2017). Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Mindfulness for Health-Related Quality of Life: Comparing Treatments for Parents of Children with Chronic Conditions - A Pilot Feasibility Study. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health : CP & EMH, 13, 1–9. http://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901713010001

Consider combing long, curly hair. Untangling the top layer is not so bad, but once half the hair is tamed, there is often a mangled mess lurking underneath. Sometimes the lumbar spine gets all the primping to relieve pain, but the sacroiliac joint is harboring the knots, such as when a lumbar rhizotomy leaves a patient’s satisfaction a little fuzzy.

A 2017 study by Rimmalapudi and Kumar investigated the incidence of sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction being diagnosed in patients after undergoing lumbar radiofrequency rhizotomy of the medial branches of lower lumbar dorsal rami for chronic facet-mediated low back pain. The authors used a retrospective chart review of 96 patients who had the procedure performed, and 50 subjects responded to the 2 follow ups and were included in the study. Their choice of control was a limitation in this study, as they compared the results to a different study (DePalma et al., 2011) with a similar population that did not have the lumbar rhizotomy performed. Of the 50 patients (66% female, 34% male), 35 (70%) were subsequently diagnosed with SI joint pain; whereas, in the comparison study, only 18% of the patients had SI pain. The assessment of SI dysfunction in this study was by clinical exam, and the DePalma et al. study used diagnostic tests. The authors concluded the following: clinicians should suspect underlying SI joint pain post-lumbar rhizotomy; careful evaluation of the SI joint should be performed pre and post procedure; and, diagnostic joint blocks should be performed to confirm SI dysfunction. They suggested using criteria of 80-100% relief as opposed to the currently accepted >50% after a diagnostic facet block because residual pain from an underlying condition may arise after lumbar rhizotomy.

A 2017 study by Rimmalapudi and Kumar investigated the incidence of sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction being diagnosed in patients after undergoing lumbar radiofrequency rhizotomy of the medial branches of lower lumbar dorsal rami for chronic facet-mediated low back pain. The authors used a retrospective chart review of 96 patients who had the procedure performed, and 50 subjects responded to the 2 follow ups and were included in the study. Their choice of control was a limitation in this study, as they compared the results to a different study (DePalma et al., 2011) with a similar population that did not have the lumbar rhizotomy performed. Of the 50 patients (66% female, 34% male), 35 (70%) were subsequently diagnosed with SI joint pain; whereas, in the comparison study, only 18% of the patients had SI pain. The assessment of SI dysfunction in this study was by clinical exam, and the DePalma et al. study used diagnostic tests. The authors concluded the following: clinicians should suspect underlying SI joint pain post-lumbar rhizotomy; careful evaluation of the SI joint should be performed pre and post procedure; and, diagnostic joint blocks should be performed to confirm SI dysfunction. They suggested using criteria of 80-100% relief as opposed to the currently accepted >50% after a diagnostic facet block because residual pain from an underlying condition may arise after lumbar rhizotomy.

Stelzer et al., (2017) published another retrospective study on lumbar neurotomy or SI joint lateral branch cooled radiofrequency (RF) neurotomy, looking at pain reduction and medication decrease, depending on BMI, gender, and sports. Facet-mediated pain is accountable for 31-45% of low back pain, and 18-30% is SI joint mediated. The study started with 160 patients who had undergone procedures, and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain scores, quality of life, BMI, medication use, and pain management satisfaction were assessed before, 1 month after (n=160), 6 months after (n=73), and 12 months (n=89) after treatment. Group 1 (n=43) had neurotomy of the medial branch of L4-5 and L5-S1 facet joint, medial branch L3 and L4, and dorsal ramus L5. Group 2 (n=109) received cooled RF treatment of the SIJ, SIJ lateral branch of the posterior rami S1–S3, and rami dorsalis of L5. Group 3 (n=8) had various areas treated according to their disease process. The authors determined from these treatments that a 95% probability of significant pain reduction could last 12 months; medication usage decreased; lower BMI had slightly better results than >30BMI; no significant difference between males and females; and, involvement in sports 1-3 times a week for 30 minutes showed improvement in quality of life.

These studies prove we need to evaluate our lumbar and sacroiliac joint patients as thoroughly as possible in order to avoid unnecessary procedures or at least to help direct the treatment to the appropriate area. We should always equip ourselves with knowledge of medical procedures our patients may undergo and expand our own clinical competence and skill. Patients benefit from what is inside our heads and how we use it, not how well-groomed our hair appears.

Rimmalapudi, V. K., & Kumar, S. (2017). Lumbar Radiofrequency Rhizotomy in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Increases the Diagnosis of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction in Subsequent Follow-Up Visits. Pain Research & Management, 2017, 4830142. http://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4830142

M. J. DePalma, J. M. Ketchum, and T. Saullo. (2011). What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Medicine. 12(2), 224–233.

Stelzer, W., Stelzer, V., Stelzer, D., Braune, M., & Duller, C. (2017). Influence of BMI, gender, and sports on pain decrease and medication usage after facet–medial branch neurotomy or SI joint lateral branch cooled RF-neurotomy in case of low back pain: original research in the Austrian population. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 183–190. http://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S121897