Does cognitive self-regulation influence the pain experience by modulating representations of nociceptive stimuli in the brain or does it regulate reported pain via neural pathways distinct from the one that mediates nociceptive processing? Woo and colleagues devised an experiment to answer this question.1 They invited thirty-three healthy participants to undergo fMRI while receiving thermal stimulation trial runs that involved 6 levels of temperatures. Trial runs included “passive experience” where participants passively received and rated heat stimuli, and “regulation” runs, where participants were asked to cognitively increase or decrease pain intensity.

Instructions for increasing pain intensity included statements such as “Try to focus on how unpleasant the pain is. Pay attention to the burning, stinging and shooting sensation.” Instructions for decreasing pain intensity included statements such as “Focus on the part of the sensation that is pleasantly warm. Imagine your skin is very cool and how good the stimulation feels as it warms you up.” The effects of both manipulations on two brain systems previously identified in the literature were examined. One brain system was the “neurological pain signature” (NPS), a distributed pattern of fMRI activity shown to specifically track pain intensity induced by noxious inputs. The second system was the pathway connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) with the nucleus accumbens (NAc), shown to play a role in both reappraisal and modulation of pain. In humans, the vmPFC tracks spontaneous pain when it has become chronic and potentially dissociated from nociception.2,3 In patients with sub-acute back pain, the vmPFC-NAc connectivity has been shown to predict subsequent transition to chronic back pain.4 In addition, the vmPCF is hypothesized to play a role in the construction of self-representations, assigning personal value to self-related contents and, ultimately, influencing choices and decisions.5

Instructions for increasing pain intensity included statements such as “Try to focus on how unpleasant the pain is. Pay attention to the burning, stinging and shooting sensation.” Instructions for decreasing pain intensity included statements such as “Focus on the part of the sensation that is pleasantly warm. Imagine your skin is very cool and how good the stimulation feels as it warms you up.” The effects of both manipulations on two brain systems previously identified in the literature were examined. One brain system was the “neurological pain signature” (NPS), a distributed pattern of fMRI activity shown to specifically track pain intensity induced by noxious inputs. The second system was the pathway connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) with the nucleus accumbens (NAc), shown to play a role in both reappraisal and modulation of pain. In humans, the vmPFC tracks spontaneous pain when it has become chronic and potentially dissociated from nociception.2,3 In patients with sub-acute back pain, the vmPFC-NAc connectivity has been shown to predict subsequent transition to chronic back pain.4 In addition, the vmPCF is hypothesized to play a role in the construction of self-representations, assigning personal value to self-related contents and, ultimately, influencing choices and decisions.5

Woo and colleagues found that both heat intensity and self-regulation strongly influenced reported pain, however they did so by two differing pathways. The NPS mediated only the effects of nociceptive input. The self-regulation effects on pain were mediated by the NAc-vmPFC pathway, which was unresponsive to the intensity of nociceptive input. The NAc-vmPFC pathway responded to both “increase” and “decrease” self-regulation conditions. Based on these results, study authors suggest that pain is influenced by both noxious input and cognitive self-regulation, however they are modulated by two distinct brain mechanisms. While the NPS encodes brain activity closely tied to primary nociceptive processing, the NAc-vmPFC pathway encodes information about evaluative aspects of pain in context. This research is limited in that the distinction between pain intensity and pain unpleasantness was not included and the subjects were otherwise healthy. Further research is warranted on the effects of this cognitive self-regulation model on brain pathways in patients with chronic pain conditions.

Even with the noted limitations, this research invites the clinician to consider the role of both nociceptive mechanisms and cognitive self-regulatory influences on a patient’s pain experience and suggests treatment choices should take both factors into consideration. Mindful awareness training is a treatment that contributes to cognitive self-regulatory brain mechanisms.6 When mindful, pain is observed as and labeled a sensation. The term “sensation” carries a neutral valence compared to “pain” which may reflect greater alarm or threat to an individual. The mind is recognized to have a camera lens-like quality that can shift from zoom to wide angle. While pain can draw attention in a more narrow focus on the painful body area, when mindful, an individual can deliberately adopt a wide angle view, focusing on pain free areas and other neutral or positive states. In addition, when mindful, the unpleasant sensation rests in awareness not characterized by fear and distress, but by stability, compassion and curiosity. Patients may not have control over the onset of pain, but with mindfulness training, they can take control over their response to the pain. This deliberate adoption of mindful principles and practices can contribute to cognitive self-regulatory brain mechanisms that can ultimately impact pain perception.

I am excited to share additional research and practical clinical strategies that help patients self-regulate their reactions to pain and other symptoms in my 2019 courses, Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals at University Hospitals in Cleveland OH, April 6 and 7 and Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment in Houston TX, October 26 and 27 and Portland OR May 18 and 19. Hope to see you there!

1. Woo CW, Roy M, Buhle JT, Wager TD. Distinct brain systems mediate the effects of nociceptive input and self-regulation on pain. PLoS;2015;13(1):e1002036.

2. Baliki MN, Chialvo DR, Geha PY, Levy RM, et al. Chronic pain and the emotional brain: specific brain activity associated with spontaneous fluctuations of intensity of chronic back pain.J Neurosci. 2006;26(47):12165-73.

3. Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain. 2013;136(pt9):2751-68.

4. Baliki MN, Peter B B, Torbey S, Herman KM, et al. Corticostriatal functional connectivity predicts transition to chronic back pain. Nat Neurosci.2012;15(8):1117-9.

5. D’Argembeau. On the role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in self-processing: The Valuation Hypothesis. Front Human Neurosci. 2013;7:372.

6. Zeidan F, Vago DR. Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief: a mechanistic account. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016 Jun;1373(1):114-27.

The British author, John Donne, wrote, “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent.” In a similar idea, no neurological symptom is independent and isolated; every system has potential to impact the whole body. Neurogenic bladder should cue a clinician to check for neurogenic bowel and to assess the pelvic floor in order to get a complete map of what to address in treatment.

Martinez, Neshatian, & Khavari (2016) reviewed literature on neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) and neurogenic bladder in patients with neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS). Constipation and fecal incontinence can coexist with NBD, and a multifactorial bowel regimen is vital to conservative management in patients with neurological disorders. Nonpharmacological, pharmacological, and surgical approaches were reviewed in the article. Specific results for MS were reported only for transanal irrigation (TAI) and biofeedback. In TAI, fluid is used to stimulate the bowel and clean out stool from the rectum. A study showed 53% of the 30 patients with MS demonstrated a 50% or better improvement in bowel symptoms with TAI. In anorectal biofeedback, operant conditioning retrains motor and sensory responses via exercises guided by manometry. With biofeedback, a study showed 38% of patients had a beneficial impact with the intervention. The list of treatment approaches not specifically researched for MS patients in this review includes: dietary modifications, perianal/anorectal stimulation, abdominal massage, suppositories, oral medications such as stool softeners or prokinetic agents, sacral neuromodulation, antegrade continence enema, and colostomy.

Martinez, Neshatian, & Khavari (2016) reviewed literature on neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) and neurogenic bladder in patients with neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS). Constipation and fecal incontinence can coexist with NBD, and a multifactorial bowel regimen is vital to conservative management in patients with neurological disorders. Nonpharmacological, pharmacological, and surgical approaches were reviewed in the article. Specific results for MS were reported only for transanal irrigation (TAI) and biofeedback. In TAI, fluid is used to stimulate the bowel and clean out stool from the rectum. A study showed 53% of the 30 patients with MS demonstrated a 50% or better improvement in bowel symptoms with TAI. In anorectal biofeedback, operant conditioning retrains motor and sensory responses via exercises guided by manometry. With biofeedback, a study showed 38% of patients had a beneficial impact with the intervention. The list of treatment approaches not specifically researched for MS patients in this review includes: dietary modifications, perianal/anorectal stimulation, abdominal massage, suppositories, oral medications such as stool softeners or prokinetic agents, sacral neuromodulation, antegrade continence enema, and colostomy.

Miletta, Bogliatto, & Bacchio (2017) presented a case study about management of sexual dysfunction, perineal pain, and elimination dysfunction in a 40 year old female with multiple sclerosis. She had been experiencing perineal pain for 5 months and had chronic MS symptoms of lower anourogenital dysfunction, including bladder retention and obstructed defecation syndrome. Physical therapy treatment included pelvic floor muscle training (primarily decreasing overactivity of pelvic muscles in this case), perineal massage, biofeedback, postural correction, global relaxation techniques, and a home self-training program. After 5 months of physical therapy, the woman had improved pelvic floor muscle contraction strength, resolution of pelvic floor muscle overactivity, increased sexual satisfaction (according to the Female Sexual Function Index score), a visual analog scale improvement of vulvar and perineal pain by 4 points, normalization of obstructed defecation syndrome, and decreased bladder retention symptoms. The authors concluded the variety of symptoms in MS require a multimodal approach for treatment, considering all the motor, autonomic, and cognitive impairments as well as side effects of medications that try to improve those symptoms. The quality of life of women with MS has potential to be improved significantly if pelvic floor disorders related to MS are addressed appropriately.

Ultimately, treating urinary dysfunction but avoiding bowel dysfunction does neurological patients a disservice. Systems are intertwined in a series of cause and effects throughout the body. The “Neurologic Conditions and the Pelvic Floor” course can expand your knowledge and understanding of how the symptoms of conditions such as multiple sclerosis can impact pelvic health and how we can better address the whole patient for optimal outcomes.

Martinez, L., Neshatian, L., & Khavari, R. (2016). Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction in Patients with Neurogenic Bladder. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports, 11(4), 334–340. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11884-016-0390-3

Miletta, M., Bogliatto, F., & Bacchio, L. (2017). Multidisciplinary Management of Sexual Dysfunction, Perineal Pain, and Elimination Dysfunction in a Woman with Multiple Sclerosis. International Journal of MS Care, 19(1), 25–28. http://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2015-082

The following is a guest submission from Alysson Striner, PT, DPT, PRPC. Dr. Striner became a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner (PRPC) in May of 2018. She specializes in pelvic rehabilitation, general outpatient orthopedics, and aquatics and treats at Carondelet St Joesph’s Hospital in the Speciality Rehab Clinic located in Tucson, Arizona.

Recently, I had a patient present with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) on his right foot. He stated that the pain had started about 10 days after his prostatectomy when someone had fallen onto his right foot. He reported a bunionectomy on that foot 7 years prior and noted an episode of plantar facilities before his prostatectomy. CRPS is defined as “chronic neurologic condition involving the limbs characterized by severe pain along with sensory, autonomic, motor, and trophic impairments” in a 2017 article "Complex regional pain syndrome; a recent update" by Goh, En Lin. The article goes on to discuss how CRPS can set off a cascade of problems including altered cutaneous innervation, central and peripheral sensitization, altered sympathetic nervous system function, circulating catecholamines, changes in autoimmunity, and neuroplasticity.

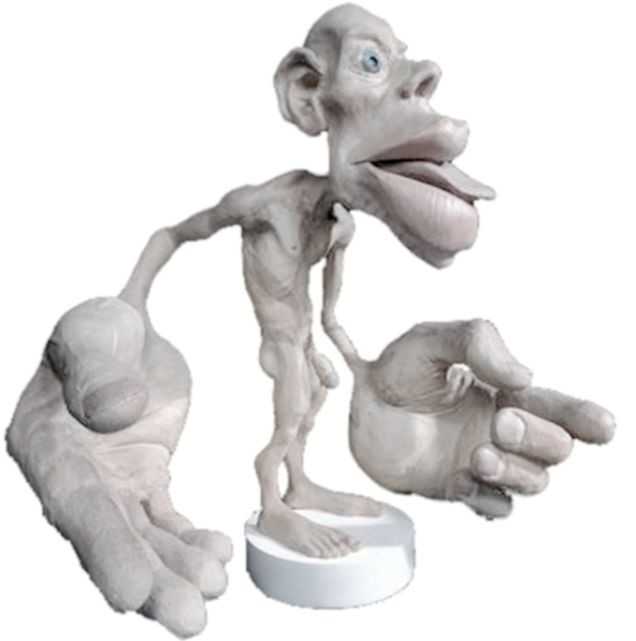

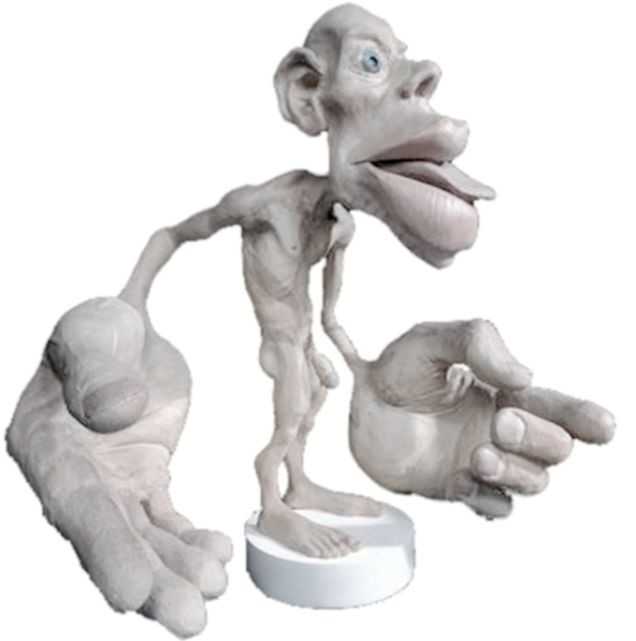

A recent persistent pain theory to explain the relationship between pelvic floor and his foot could be overflow or ‘smudging’ in his homunculus. The homunculus is the map of our physical body in our brain where the feet are located next to the genitals. Possibly when one has pain, there can be ‘smudging’ of our mental body map from one area into another. I have heard this explained as though a chalk or charcoal drawing has been swipes their hand through the picture. A recent study by Schrabrun, SM et al “Smudging of the Motor Cortex is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain” found that people with chronic low back pain had a loss of cortical organization which and that this loss was associated with the severity and location of LBP.

A recent persistent pain theory to explain the relationship between pelvic floor and his foot could be overflow or ‘smudging’ in his homunculus. The homunculus is the map of our physical body in our brain where the feet are located next to the genitals. Possibly when one has pain, there can be ‘smudging’ of our mental body map from one area into another. I have heard this explained as though a chalk or charcoal drawing has been swipes their hand through the picture. A recent study by Schrabrun, SM et al “Smudging of the Motor Cortex is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain” found that people with chronic low back pain had a loss of cortical organization which and that this loss was associated with the severity and location of LBP.

There are many ways to improve the organization of the homunculus and create neuroplasticity. One such way was suggested is with Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) to the bottom of the foot to affect bladder spasms and pain. In recent study, “Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of somatic afferent nerves of the foot relieved symptoms related to postoperative bladder spasms,". Zhang, C et al. 2017 found that participates that had either a bladder surgery or a prostate surgery had improvement in bladder spasm symptoms and VAS scores on day two and three. Their protocol was to use two electrodes over the bottom of the foot at 5 Hz with 0.2 millisecond pulse width until a muscle twitch was achieved and was increased, but still comfortable for an hour (there is a picture of electrode placement in the article). The authors note that this neuromodulation of the foot sensory nerves may inhibit interactions between the somatic peripheral neuropathway and autonomic micturition reflex to calm the bladder and pain.

No matter what we do to help calm nervous systems from the top down; pain neuroscience education, mindful based relaxation, graded motor imagery, or from the bottom up; de-sensitization, biofeedback, or good old-fashioned TENS. The result is the same; a cortical organization and happier patients.

En Lin Goh†, Swathikan Chidambaram† and Daqing Ma. "Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update". Burns & Trauma 2017 5:2.https://doi.org/10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4"

Schabrun SM, Elgueta-Cancino EL, Hodges PW. "Smudging of the Motor Cortex Is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain." Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017 Aug 1;42(15):1172-1178. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000938

Chanjuan Zhang, et al. "Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of somatic afferent nerves in the foot relieved symptoms related to postoperative bladder spasms". BMC Urol. 2017; 17: 58. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0248-9

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC is the author and instructor of Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab, a new course coming to Grand Rapids, MI and Philadelphia, PA. This post is the next in her series on creating a course about neurologic conditions and pelvic rehabilititation.

Being a clinician, as we evaluate and treat people with pelvic health conditions, we typically take all systems of the body into account. We take the problem presented to us by the client and we examine, from all angles, how we might go about advice and treatment to best achieve their goals in alleviating the problem. We do a full review of medical history and pharmacology. We examine our client in-depth from a musculoskeletal perspective. We look at psychological contributions to the problem they are facing. We can look at their lifestyle and have them make a detailed diary to help us analyze their bladder, bowel, fluid intake and dietary habits. Do we also always include a look at the neurological components? Do we know what we are looking for? What are the best tools we can have in our toolbox as clinicians to look at our client’s problem through a “neuro brain”?

In writing each lecture of this course, I have had to step back each time I am developing a new concept and look at it with in-depth thought and contemplation about how I will use this in the clinic to assess my client’s concerns using a neuro-based approach. Taking the concepts and facts about the musculoskeletal system that we know well and then taking a look at the neurological systems contributions and relationship to that dysfunction can be challenging. The main reason for this challenge is that neuro system dysfunction is many times hard explain, presents with inconsistent or changing symptoms, may have motor or sensory deficits together or by themselves, may radiate to different locations than where the true dysfunction is located, and may have developed into central sensitization causing a hypervigilance to typically non-painful stimuli.

In writing each lecture of this course, I have had to step back each time I am developing a new concept and look at it with in-depth thought and contemplation about how I will use this in the clinic to assess my client’s concerns using a neuro-based approach. Taking the concepts and facts about the musculoskeletal system that we know well and then taking a look at the neurological systems contributions and relationship to that dysfunction can be challenging. The main reason for this challenge is that neuro system dysfunction is many times hard explain, presents with inconsistent or changing symptoms, may have motor or sensory deficits together or by themselves, may radiate to different locations than where the true dysfunction is located, and may have developed into central sensitization causing a hypervigilance to typically non-painful stimuli.

In brain storming our ideas for course creation, much was said about thinking back to college or other continuing education courses and “learning a little about a lot of things neuro” but not the in-depth knowledge one might want to have when focusing their attention on specific neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson disease, demyelinating diseases such as Multiple Sclerosis, injury to the brain due to cerebral vascular accident or incomplete or complete spinal cord injury.

As I progress deep into the development of this course, I have my “neuro brain” on and a persistent focus set on providing clinicians with as much in-depth information on neurological contributions to pelvic floor function and dysfunction. I want clinicians to walk away from this course feeling confident that through evaluation of a client that has been diagnosed with Parkinson disease, Multiple Sclerosis or suffered a spinal cord injury, they would have the tools to develop an in-depth treatment plan that would provide these clients with the best results possible to improve their quality of life. I also want clinicians to have the confidence to market themselves to their local neurologists. This is an entirely new avenue for developing a referral base in pelvic health work. Many times for clients who have chronic neurological conditions, the problem list is long and bladder, bowel and sexual health concerns might not even be broached within the very short physician appointment times. We can give our neurologists new treatments to be confident in and excited about to improve their patient’s quality of life!

Neurophysiology is a dynamic and highly complex system of neurological connections and interactions that allow for bodily performance. When all of those connections are working correctly, our bodies can function at optimal levels. When there is a break or injury to those connections, dysfunction results but amazingly in some circumstances, our bodies have work arounds to allow for certain functions to continue working.

If we take the sexual neural control system of the male, for instance, a perfect example of this can be described. Many men were injured fighting in World War II. During their time in battle, many experienced spinal cord injuries. Some of these injuries were severe resulting in complete spinal cord damage at level of injury. A physician, Herbert Talbot, in 1949, documented his examination of 200 men with paraplegia. Two thirds of the men were surprisingly able to achieve erections and some were able to experience vaginal penetration and orgasm. Much of their basic functionality had been lost however amazingly there was preservation of erectile function.

The reason these men with paraplegia were able to maintain erectile or orgasm functionality is due to the physiological function in the sacral spinal cord. A reflex arc is present in this region. The definition of a reflex arc is a nerve pathway that has a reflexive action involving sensory input from a peripheral somatic or autonomic nerve synapsing to a relay neuron or interneuron in the sacral cord segment then synapsing to a motor nerve for output to the muscular region. These messages do not need to travel up the spinal cord to the brain in order to be activated. Instead they work within a ‘loop’ at the sacral spinal cord level. In the case of spinal cord injury, erectile function as well as other functions controlled by reflex arcs, can be preserved.

For women, the same is true. In order for a female to have engorgement of the clitoris or orgasm, the sacral spinal reflex arc needs to be intact. If a woman experiences a spinal cord injury above the sacral region, the ability to have a reflexive orgasm within the sacral spinal reflex arc will remain.

The sacral reflex arc also plays an important role in activation of the pelvic floor muscles during the sexual response cycle. During genital stimulation in both the male and female, the bulbospongiosus or bulbocavernosus begins to activate in a reflexive pattern to hinder the outflow of blood from the region which facilitates erectile tissue of the penis and clitoris to become erect. This can then be followed by rhythmic reflexive contractions of the pelvic floor musculature during orgasm.

To learn more about the implications that neurologic disorders can have on the sexual system, please join us for Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab, coming to Grand Rapids, MI in September.

Goldstein, I. (2000). Male sexual circuitry. Scientific American, 283(2), 70-75.

Sipski, M. L. (2001). Sexual response in women with spinal cord injury: neurologic pathways and recommendations for the use of electrical stimulation. The journal of spinal cord medicine, 24(3), 155-158.

Wald, A. (2012). Neuromuscular Physiology of the Pelvic Floor. In Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract (Fifth Edition)(pp. 1023-1040).