Urinary incontinence (UI) can be problematic for both men and women, however, is more prevalent in women. Incontinence can contribute to poor quality of life for multiple reasons including psychological distress from stigma, isolation, and failure to seek treatment. Patients enduring incontinence often have chronic fear of leakage in public and anxiety about their condition. There are two main types of urinary leakage, stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urge urinary incontinence (UUI).

SUI is involuntary loss of urine with physical exertion such as coughing, sneezing, and laughing. UUI is a form of incontinence in which there is a sudden and strong need to urinate, and leakage occurs, commonly referred to as “overactive bladder”. Currently, SUI is treated effectively with physical therapy and/or surgery. Due to underlying etiology, UUI however, can be more difficult to treat than SUI. Often, physical therapy consisting of pelvic floor muscle training can help, however, women with UUI may require behavioral retraining and techniques to relax and suppress bladder urgency symptoms. Commonly, UUI is treated with medication. Unfortunately, medications can have multiple adverse effects and tend to have decreasing efficacy over time. Therefore, there is a need for additional modes of treatment for patients suffering from UUI other than mainstream medications.

An interesting article published in The Journal of Alternative and Complimentary Medicine reviews the potential benefits of yoga to improve the quality of life in women with UUI. The article details proposed concepts to support yoga as a biobehavioral approach for self-management and stress reduction for patients suffering with UUI. The article proposes that inflammation contributes to UUI symptoms and that yoga can help to reduce inflammation.

Surfacing evidence indicates that inflammation localized to the bladder, as well as low-grade systemic inflammation, can contribute to symptoms of UUI. Research shows that women with UUI have higher levels of serum C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation), as well as increased levels of inflammatory biomarkers (such as interleukin-6). Additionally, when compared to asymptomatic women and women with urgency without incontinence, patients with UUI have low-grade systemic inflammation. It is hypothesized that the inflammation sensitizes bladder afferent nerves through recruitment of lower threshold and typically silent C fiber afferents (instead of normally recruited, higher threshold A-delta fibers, that respond to stretch of the bladder wall and mediate bladder fullness and normal micturition reflexes). Therefore, reducing activation threshold for bladder sensory afferents and a lower volume threshold for voiding, leading to the UUI.

How can yoga help?

Yoga can reduce levels of inflammatory mediators. According to the article, recent research has shown that yoga can reduce inflammatory biomarkers (such as interleukin -6) and C-reactive protein. Decreasing inflammatory mediators within the bladder may reduce sensitivity of C fiber afferents and restore a more normalized bladder sensory nerve threshold.

Studies suggest that women with UUI have an imbalance of their autonomic nervous system. The posture, breathing, and meditation completed with yoga practice may improve autonomic nervous system balance by reducing sympathetic activity (“fight or flight”) and increasing parasympathetic activity (“rest and digest”).

The discussed article highlights yoga as a logical, self-management treatment option for women with UUI symptoms. Yoga can help to manage inflammatory symptoms that directly contribute to UUI by reducing inflammation and restoring autonomic nervous system balance. Additionally, regular yoga practice can improve general well-being, breathing patterns, and positive thinking, which can reduce overall stress. Yoga provides general physical exercise that improves muscle tone, flexibility, and proprioception. Yoga can also help improve pelvic floor muscle coordination and strength which can be helpful for UUI. Yoga seems to provide many benefits that could be helpful for a patient with UUI.

In summary, UI remains a common medical problem, in particular, in women. While SUI is effectively treated with both conservative physical therapy and surgery, long-term prescribed medication remains the treatment modality of choice for UUI. However, increasing evidence, including that described in this article, suggests that alternative conservative approaches, such as yoga and exercise, may serve as a valuable adjunct to traditional medical therapy.

Tenfelde, S., & Janusek, L. W. (2014). Yoga: a biobehavioral approach to reduce symptom distress in women with urge urinary incontinence. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20(10), 737-742.

In manual therapy training, we do not learn just one position to mobilize a joint, so why should pelvic floor muscle training be limited by the standard training methods? There is almost always at least one patient in the clinic that fails to respond to the “normal” treatment and requires a twist on conventional therapy to get over a dysfunction. Thankfully, classes like “Integrative Techniques for Pelvic Floor and Core Function” provide clinicians with the extra tools that might help even just one patient with lingering symptoms.

In 2014, Tenfelde and Janusek considered yoga as a treatment for urge urinary incontinence in women, referring to it as a “biobehavioral approach.” The article reviews the benefits of yoga as it relates to improving the quality of life of women with urge urinary incontinence. Yoga may improve sympatho-vagal balance, which would lower inflammation and possibly psychological stress; therefore, the authors suggested yoga can reduce the severity and distress of urge UI symptoms and their effect on daily living. Since patho-physiologic inflammation within the bladder is commonly found, being able to minimize that inflammation through yoga techniques that activate the efferent vagus nerve (which releases acetylcholine) could help decrease urge UI symptoms. The breathing aspect of yoga can reduce UI symptoms as it modulates neuro-endocrine stress response symptoms, thus reducing activation of psychological and physiologic stress and inflammation associated with stress. The authors concluded the mind-body approach of yoga still requires systematic evaluation regarding its effect on pelvic floor dysfunction but offers a promising method for affecting inflammatory pathways.

In 2014, Tenfelde and Janusek considered yoga as a treatment for urge urinary incontinence in women, referring to it as a “biobehavioral approach.” The article reviews the benefits of yoga as it relates to improving the quality of life of women with urge urinary incontinence. Yoga may improve sympatho-vagal balance, which would lower inflammation and possibly psychological stress; therefore, the authors suggested yoga can reduce the severity and distress of urge UI symptoms and their effect on daily living. Since patho-physiologic inflammation within the bladder is commonly found, being able to minimize that inflammation through yoga techniques that activate the efferent vagus nerve (which releases acetylcholine) could help decrease urge UI symptoms. The breathing aspect of yoga can reduce UI symptoms as it modulates neuro-endocrine stress response symptoms, thus reducing activation of psychological and physiologic stress and inflammation associated with stress. The authors concluded the mind-body approach of yoga still requires systematic evaluation regarding its effect on pelvic floor dysfunction but offers a promising method for affecting inflammatory pathways.

Pang and Ali (2015) focused on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments for interstitial cystitis (IC) and bladder pain syndrome (BPS). Since conventional therapy has not been definitely determined for the IC/BPS population, CAM has been increasingly used as an optional treatment. Two of the treatments under the CAM umbrella include yoga (mind-body therapy) and Qigong (an energy therapy). Yoga can contribute to IC/BPS symptom relief via mechanisms that relax the pelvic floor muscle. Actual yoga poses of benefit include frog pose, fish pose, half-shoulder stand and alternate nostril breathing. According to a systematic review, Qigong and Tai Chi can improve function, immunity, stress, and quality of life. Qigong has been effective in managing chronic pain, although not specifically evidenced with IC/BPS groups. Qigong has also been shown to reduce stress and anxiety and activate the brain region that suppresses pain. The CAM gives a multimodal approach for treating IC/BPS, and this has been recommended by the International Consultation on Incontinence Research Society.

Evidence is emerging in every area of treatment these days, so it is only a matter of time before randomized controlled trials regarding alternative treatment methods for the pelvic floor begin to fill pages of our professional journals. Yoga, Qigong, Tai Chi, biologically based therapies, manipulative and body-based approaches, and whole medical systems all offer safe, effective treatment options for the IC/BPS and urinary incontinence patient populations. The more we use these extra treatment tools and document the results, the more likely we will see clinical trials proving their efficacy.

Tenfelde, S and Janusek, L. (2014). Yoga: A Biobehavioral Approach to Reduce Symptom Distress in Women with Urge Urinary Incontinence. THE JOURNAL OF ALTERNATIVE AND COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE. 20 (10), 737–742. http://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2013.0308

Pang, R., & Ali, A. (2015). The Chinese approach to complementary and alternative medicine treatment for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome.Translational Andrology and Urology, 4(6), 653–661. http://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.08.10

Today's blog is a contribution from Kristen Digwood, DPT, CLT, of the Elite Pelvic Rehab clinic in Wilkes-Barre, PA.

Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), which is the involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency, is a common health problem in the female population. The effects of UUI result in limitations to daily activity and quality of life.

Current guidelines recommend conservative management as a first-line therapy in urinary incontinence, defined as "interventions that do not involve treatment with drugs or surgery targeted to the type of incontinence".

Electrical stimulation is commonly used as part of a treatment program for women with UUI. There are several methods and parameters that can be used to improve urge incontinence, however the magnitude of the alleged benefits and best parameters is not completely established. Studies have suggested that the use of electrical stimulation to inhibit an overactive bladder functions to modulate unwanted detrusor contractions by way of sensory afferent stimulation of S2 and S3. This causes parasympathetic inhibition. In addition to this effect, contraction of the pelvic floor muscles results in inhibition and relaxation of the detrusor muscle which reduces urinary urgency.

Electrical stimulation is commonly used as part of a treatment program for women with UUI. There are several methods and parameters that can be used to improve urge incontinence, however the magnitude of the alleged benefits and best parameters is not completely established. Studies have suggested that the use of electrical stimulation to inhibit an overactive bladder functions to modulate unwanted detrusor contractions by way of sensory afferent stimulation of S2 and S3. This causes parasympathetic inhibition. In addition to this effect, contraction of the pelvic floor muscles results in inhibition and relaxation of the detrusor muscle which reduces urinary urgency.

Common methods of electrical stimulation include suprapubical, transvaginal, sacral and tibial nerves stimulation.

As with any medical treatment, practitioners seek the most effective methods and parameters to achieve the patient’s goals. A recent systematic review of electrical stimulation in the treatment of UUI included nine trials to treat UUI were included with total of 534 female patients. Most patients in the trials were close to 55 years of age. Five articles (total of nine) described a frequency of twice-weekly therapy and sessions of 20 minutes. Twelve weeks was the most common duration of therapy. All the studies applied an intensity of stimulation below 100 mA, with four of them (4/9) using 10 hz as the frequency. Intervaginal electrical stimulation showed the greatest subjective improvement and was the most effective.

The most frequent outcome measure was bladder diary, used in all papers; subjective satisfaction was used in 8; and quality-of-life questionnaires in 6, from a total of 9 papers.

The study noted that reports about electrical stimulation generally lack information on its cost-effectiveness. This is an important point, especially because in therapies with similar benefits cost may be one of the factors to indicate the most appropriate treatment. If we consider the relatively few adverse effects, low cost, and similar effectiveness when compared to medication, intravaginal electrical stimulation, according to available data, appears to be a good alternative treatment for UUI.

1. Thüroff JW, Abrams P, Andersson KE, Artibani W, Chapple CR, Drake MJ, et al.: EAU guidelines on urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2011; 59: 387-400.

2. Kralj B. The treatment of female urinary incontinence by functional electrical stimulation. In:Ostergard DR, Dent AD (eds). Urogenecology and Urodynamics. 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1991.

3. Eriksen, BC. Electrical Stimulation. In: Benson JT editor. Female pelvic floor disorders: investigation and management. New York:Norton, 1992; 219-231.

4. Lucas Schreiner , Thais Guimarães dos Santos , Alessandra Borba Anton de Souza, et al. Int. braz j urol. vol.39 no.4 Rio de Janeiro July/Aug. 2013.

The following comes to us from Felicia Mohr, DPT, a guest contributor to the Pelvic Rehab Report.

Vaginal mesh kits were used frequently early in the millennium as they led to high initial anatomic success rates with peak use between 2008 and 2010. Objectively they seemed to help elevate women’s pelvic organs to appropriate anatomical locations. Unfortunately there has been a high rate (10% according to a review of current literature on PubMedBarski 2015) of mesh erosion causing recurrent prolapse and/or stress urinary incontinence. Also there are cases when the mesh product perforates surrounding organs causing numerous dangerous complications. The rate of mesh-related complications according to current research is 15-25%. As a result, the FDA has reclassified the risk of synthetic mesh into a higher risk category so that the public has an increased awareness of the risk involved in these types of surgeries.

A systematic review and meta-analysis, published in 2015, reviewed the risk factors for mesh erosion following female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery (Deng, et al). They concluded the following factors increase risk of mesh erosion: younger age, more childbirths, premenopausal states, diabetes, smoking, concomitant hysterectomy, and surgery performed by a junior surgeon. Moreover, concomitant POP surgery and preservation of the uterus may be the potential protective factors for mesh erosion.

A systematic review and meta-analysis, published in 2015, reviewed the risk factors for mesh erosion following female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery (Deng, et al). They concluded the following factors increase risk of mesh erosion: younger age, more childbirths, premenopausal states, diabetes, smoking, concomitant hysterectomy, and surgery performed by a junior surgeon. Moreover, concomitant POP surgery and preservation of the uterus may be the potential protective factors for mesh erosion.

It is a common practice to perform a hysterectomy with a POP surgery. Reason being that the oversized uterus from childbearing adds extra weight on pelvic organs. However, the latter study as well as two other recent studies published in 2015 (Huang, Farthmann) also provide evidence that there is no benefit to a concomitant hysterectomy at the 2.5 year follow up and can lead to less satisfaction with surgery according to patient surveys respectively.

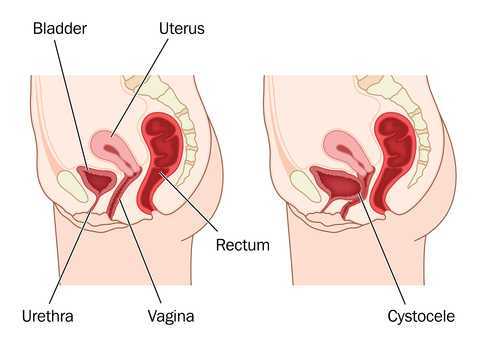

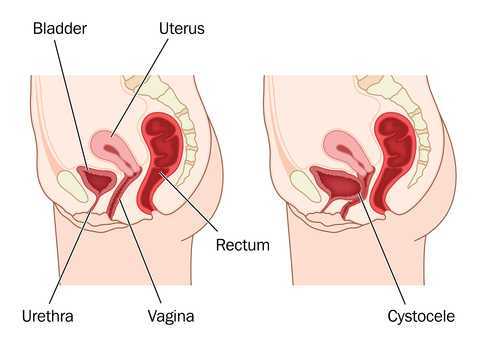

Keep in mind that all pelvic floor surgeries do not use the same amount of mesh material and different procedures have different risks associated with them. One retrospective study (Cohen, 2015) addressing incidence of mesh extrusion categorized 576 subjects into three categories: pubo-vaginal sling (PVS) (a small string of mesh around the urethra specifically addressing stress urinary incontinence only); PVS and anterior repair (also referred to as cystocele or bladder prolapse); and PVS with anterior and/or posterior repairs (also referred to as rectocele or rectal prolapse). Mesh extrusion for these types of procedures occurred at the follow rates: approximately 6% for PVS subjects, 15% for PVS + anterior repair, and 11% for PVS + anterior and/or posterior repair. This study did not account for any other types of mesh-related complications.

Pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence make up some of the most common conditions for which patients seek Pelvic Floor physical therapy and perhaps this will allow us to better speak to current research on surgical options.

1. Barski D, Deng EY. Management of Mesh Complications after stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolaps repair: review and analysis of the current literature. Biomed Research International; 2015Article ID 831285.

2. Deng T. et al. Risk factor for mesh erosion after female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU International. Doi:10.1111/bju.13158.

3. Huang LY, et al. Medium-term comparison of uterus preservation versus hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse treatment with prolift mesh. International Urogynecology Journal. 2015;26(7):1013-20.

4. Farthmann J, et al. Functional outcome after pelvic floor reconstructive surgery with or without concomitant hysterectomy. Archives of Gynec and Obstet. 2015; 291(3):573-7.

5. Cohen S, Kaveler E. The incidence of mesh extrusion after vaginal incontinence and pelvic floor prolapse surgery. J of Hospital Admin. 2014; 3(4): www.sciedu.ca/jha.

The following post comes to us from long-time faculty member Dawn Sandalcidi PT, RCMT, BCB-PMD! Dawn is a figurehead in the world of pediatric pelvic floor, she teaches Pediatric Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (available three times in 2016) and she just completed the 2nd edition of the Pediatric Pelvic Floor Manual!! Today Dawn is sharing her insights an urotherapy for pediatric patients.

If you read any papers on pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction you will often come across the word "urotherapy". It is by definition a conservative based management based program used to treat lower urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction using a variety of health care professionals including the physician, Physical Therapists, Occupational Therapists and Registered Nurses.

If you read any papers on pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction you will often come across the word "urotherapy". It is by definition a conservative based management based program used to treat lower urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction using a variety of health care professionals including the physician, Physical Therapists, Occupational Therapists and Registered Nurses.

Basic urotherapy includes education on the anatomy and function of the LUT, behavior modifications including fluid intake, timed or scheduled voids, toilet postures and avoidance of holding maneuvers, diet, bladder irritants and constipation. This needs to be tailored to the patients’ needs. For example a child with an underactive bladder needs to learn how to sense urge and listen to their body and a child who postpones a void needs to be on a voiding schedule. Urotherapy alone can be helpful however a recent study demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in uroflow, pelvic floor muscle electromyography activity during a void, urinary urgency, daytime wetting and reduced post void residual (PVR) in those patients who received pelvic floor muscle training as compared to Urotherapy alone. This is great news for all of us who are qualified to teach pelvic floor muscle exercise!

The International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) has now expanded the definition of Urotherapy to include Specific Urotherapy. This includes biofeedback of the pelvic floor muscles by a trained therapist who is able to teach the child how to alter pelvic floor muscle activity specifically to void. It also includes neuromodulation for many types of lower urinary tract dysfunction but most commonly with overactive bladder and neurogenic bladder. Cognitive behavioral therapy and psychotherapy are always important to assess (see blog post on psychological effects of bowel and bladder dysfunction).

It truly does take a village to help this kiddos and I am honored to be a team player!

To learn more about pediatric incontinence and pelvic floor rehabilitation, join Dawn Sandalcidi at one of her courses this year! Details at the following links:

Pediatric Incontinence - Augusta, GA - Apr 16, 2016 - Apr 17, 2016

Pediatric Incontinence - Torrance, CA - Jun 11, 2016 - Jun 12, 2016

Pediatric Incontinence - Waterford, CT - Sep 17, 2016 - Sep 18, 2016

Chang SJ, Laecke EV, Bauer, SB, von Gontard A, Bagli,D, Bower WF,Renson C, Kawauchi A, Yang SS-D. Treatment of daytime urinary incontinence: a standardization document from the international children's continence society. Neurourol Urodyn 2015;Oct 16. doi:10.1002/nau.22911

Ladi Seyedian SS, Sharifi-Rad L, Ebadi M, Kajbafzadeh AM. Combined functional pelvic floor muscle exercise with swiss ball and Urotherapy for management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr.2014 Oct;173(10):1347-53. I.J.N. Koppen, A. von Gontard, J. Chase, C.S. Cooper, C.S. Rittig, S.B. Bauer, Y. Homsy, S.S. Yang, M.A. Benninga. Management of functional nonretentive fecal incontinence in children: recommendations from the International Children’s Continence Society. J of Ped Urol (2015)

Koppen IJ, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Dinning PG, Yacob D, Levitt MA, Benninga MA. .Childhood constipation: finally something is moving! Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Oct 14:1-15.

Since the passing of Title IX in 1972, which protects people from sex discrimination in education or activity programs receiving federal funding, the number of females participating in sports has greatly increased. The National Federation of State High School Associations states that in 2011 nearly 3.2 million girls are participating in high school sports.

Unfortunately, a consequence of this increased participation in sports is a higher prevalence in urinary incontinence (UI) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in female athletes. Borin et al looked at the ability of nulliparous female athletes to generate intracavity perineal pressure in comparison to nonathletic women. The study demonstrated that higher mean pressures were generated by nonathletic women in comparison to the athletic women group and that lower perineal pressures in the athletic women were also related to number of games per year and time spent on sport specific workouts and strength training workouts.

UI and SUI are underreported in the general population and also in the athletic population. As health care professionals it is important to screen for UI and SUI in our clients. Physical therapy interventions using pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation have shown to decrease the severity of UI and SUI (Rivalta et al, Hulme). Rivalta used internal methods to improve the function of the pelvic floor muscle. Hulme’s success was achieved through activation of the pelvic floor muscles’ extrinsic synergists.

|

|

Pilates is often used in physical therapy as a therapeutic tool to improve lumbar stability with studies showing increases in abdominal strength (Sekendiz), trunk extensor endurance (Sekendiz) and to improve posture (Kloubec). Pilates is often also used in pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation and can easily be modified for low level clients. For example the use of resistance can assist supporting the weight of the leg. Practical proof, while lying supine in neutral lumbar spine position, stretch an arm and a leg away from center, notice the difficulty to maintain neutral spine. Now hold a resistance strap, which is also attached to the foot, and notice how maintaining neutral lumbar spine is easier to maintain (pictured above).

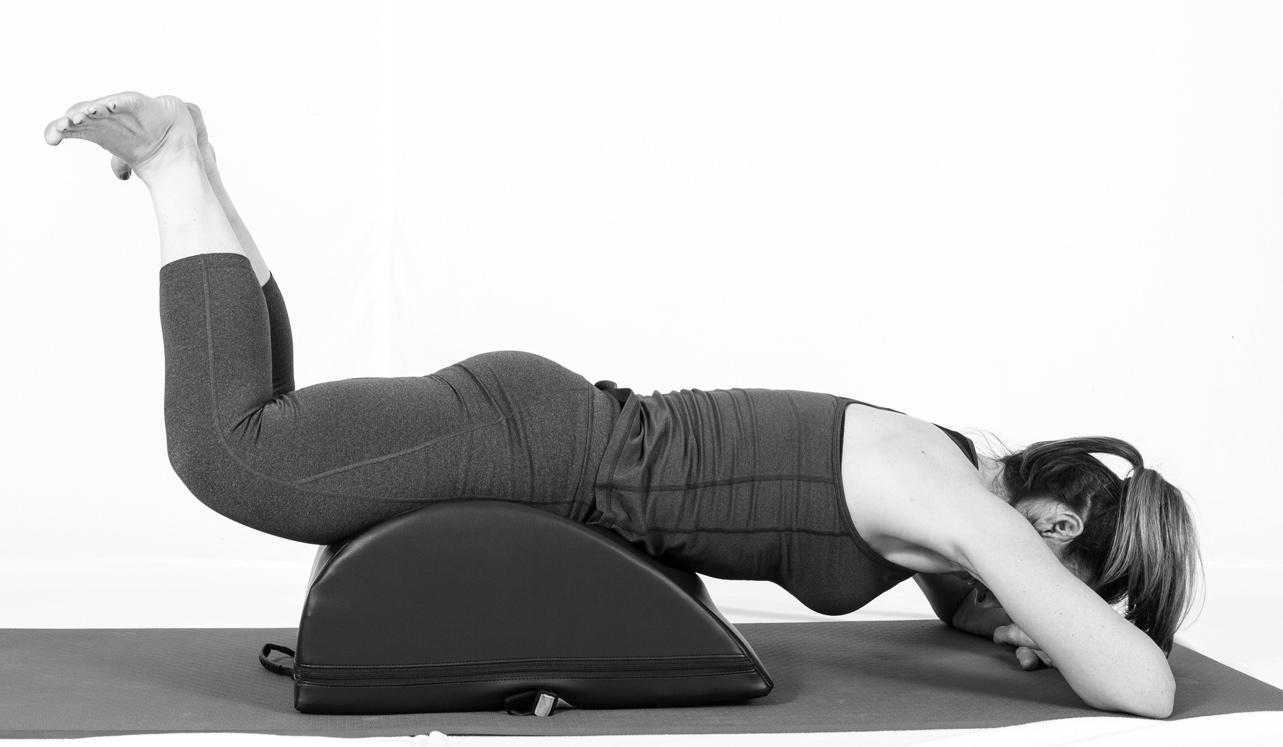

Pilates can also be modified for the higher level client or more athletic client. The use of arc barrels, BOSUs or the Hooked on Pilates MINIMAX (pictured belowy) allow the athletic client to achieve an inverted position, unloading the pelvic floor muscles. In the inverted position, pelvic floor muscles may be activated as intrinsic and/or extrinsic synergists of the pelvic floor muscles are also activated. These types of exercises may be more appealing to the athletic client ensuring continuation of the exercise post discharge from physical therapy.

|

|

Borin LC, Nunes FR, Guirro EC. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle pressure in female athletes. PMR. 2013; 5(3):189-193.

Hulme, Janet. Beyond Kegels 3rd edition, 2012 Phoenix Publishing Co. Missoula, Montana

Kloubec JA. Pilates for improvement of muscle endurance, flexibility, balance and posture. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:661-667.

Rivalta M, Sughunolfi MC, Micali S, De Stafani S, Torcasio F, Bianchi G, Urinary incontinence and sport. First and preliminary experience with a combined pelvic floor rehabilitation program in three female athletes. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(5);330-334.

Sekendiz B, Altun O, Korkusuv F, Akin S, Effects of pilates exercise on trunk strength, endurance and flexibility in sedentary adult females. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2005;9:52-57.

Occasionally, as pelvic rehab providers, we will encounter the question from our patients, “Do vaginal weights help with urinary incontinence and pelvic floor performance?” The premise behind the use of vaginal cones or balls is that holding them actively in your vagina with your pelvic floor muscles helps to increase the performance (strength and endurance) of the pelvic floor muscles, assisting in reduction of urinary incontinence.

Of the searched studies, all were randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials. The primary outcomes of the searched studies were pelvic floor muscle performance (strength or endurance) and/or urinary incontinence, both assessed with a valid or reliable method. 37 potentially useful articles were reviewed out of 1324 based on the search criteria, but only one article met all of the inclusion criteria and was included in this review with 192 relevant participants (Wilson and Herbison).

In the included study, the group that used vaginal cones (compared to control group) showed a statistically significant lower rate of urinary incontinence. However, when compared to the pelvic exercises group, the continence rates were similar at 12 months post-partum between the cone group and the exercising group. At 24-44 months post-partum, continence rates amongst all groups were similar, but follow-up rates were very low.

As pelvic rehabilitation providers, it is our job to promote pelvic health and assist our post-partum patients with their pelvic impairments, providing them with options to meet their goals. This review does not make a scientific statement of a preferred mode of pelvic exercise, however, it gives us one more option to consider when teaching patients about how to improve pelvic muscle performance to increase urinary continence following child birth. Pelvic exercise enhances pelvic performance, so if your patient would prefer to use vaginal cones or balls to do their pelvic exercise versus completing pelvic exercises without them, do what works best for the patient. One can argue that any pelvic exercise is better than none in improving performance. The use of vaginal cones or balls may be helpful for urinary continence in post-partum women, and provides us with one tool more when promoting pelvic health in our patients.

Oblasser, C., Christie, J., & McCourt, C. (2015). Vaginal cones or balls to improve pelvic floor muscle performance and urinary continence in women post-partum: A quantitative systematic review. Midwifery, 31(11), 1017-1025.

Wilson, P. D., & Herbison, G. P. (1998). A randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle exercises to treat postnatal urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal, 9(5), 257-264.

While working with a 71 year old lady one day, I asked her about her sleep habits, thinking she would describe her neck position, since that it was I was treating. She quickly commented she gets up one to two times every night to use the bathroom. Without any hesitation, she then declared her sister and her friends all do the same thing. No one she knows who is close to her age can sleep through the night without having to pee. Realizing this was more of an issue for my patient than her neck at night, I proceeded to look into the research behind these nighttime escapades of the elderly.

In the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine in 2013, Zeitzer et al. performed research regarding insomnia and nocturia in older adults. The introduction explains how 40-70% of older adults experience insomnia, and the greatest cause for sleep disturbance is the need to urinate in the middle of the night (nocturia). In epidemiological studies, between two-thirds and three-quarters older adults report disrupted sleep due to nocturia. The study performed by these authors involved men (average age of 64.3) and women (average age of 62.5) recording their sleep and toileting habits over the course of 2 weeks. The results showed over half the reported awakenings at night were secondary to nocturia. They had worse restfulness and efficiency of sleep associated with the log-reported need to get up to use the bathroom.

In a 2014 study by Tyagi, et al., the effect of nocturia on the behavioral treatment for insomnia in older adults was explored. The authors noted how nocturia being the primary reason for waking up at night increased proportionately with age with results ranging from 39.9% in people 18-44 years of age to 77.1% in the 65 years old or above population. The 79 participants in this study underwent brief behavioral treatment for their chronic insomnia or only received information. People with and without nocturia both demonstrated significant improvements in quality of sleep after receiving brief behavioral treatment versus the control group; however, the effect size was larger in the participants without nocturia. The authors concluded nocturia needs to be addressed first in order to experience the full benefit of behavior treatment for insomnia.

In a 2014 study by Tyagi, et al., the effect of nocturia on the behavioral treatment for insomnia in older adults was explored. The authors noted how nocturia being the primary reason for waking up at night increased proportionately with age with results ranging from 39.9% in people 18-44 years of age to 77.1% in the 65 years old or above population. The 79 participants in this study underwent brief behavioral treatment for their chronic insomnia or only received information. People with and without nocturia both demonstrated significant improvements in quality of sleep after receiving brief behavioral treatment versus the control group; however, the effect size was larger in the participants without nocturia. The authors concluded nocturia needs to be addressed first in order to experience the full benefit of behavior treatment for insomnia.

On a neurological level, a study from November 2015 by Smith, Kuchel, and Griffiths reported there could be a neural basis for voiding dysfunction in older adults. They found 3 separate neural circuits control voiding, and damage to the pathways feeding these circuits increases with age and can increase urge incontinence. Older adults experiencing neurological deficits may have difficulty discerning what to do when there is urgency and are susceptible to becoming incontinent. The authors recommend treatment of not just the bladder in older people but also therapies to address the structural and functional abnormalities of the neural circuits to provide the greatest results.

So, the next time I saw my patient, I explained to her she is definitely not alone in her nightly rendezvous to the bathroom when it comes to her age group. She has accepted this as “just how things are.” I would like to think there is something more we can do for the elderly population to keep them out of the nocturia “night club.” Taking the Geriatric Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation course by Heather S. Rader, PT, DPT, BCB-PMD, seems like an essential step in the right direction.

Tyagi, S., Resnick, N. M., Perera, S., Monk, T. H., Hall, M. H., & Buysse, D. J. (2014). Behavioral Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Older Adults: Does Nocturia Matter? Sleep, 37(4), 681–687.

Zeitzer, J. M., Bliwise, D. L., Hernandez, B., Friedman, L., & Yesavage, J. A. (2013). Nocturia Compounds Nocturnal Wakefulness in Older Individuals with Insomnia. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 9(3), 259–262.

Smith, Phillip P., Kuchel, George A., Griffiths, Derek. (2015). Functional Brain Imaging and the Neural Basis for Voiding Dysfunction in Older Adults. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 31(4), 549–565.

The 2012 guidelines for the treatment of overactive bladder in adults (updated in 2014) recommends as first line treatment behavioral therapies. These therapies include bladder training, bladder control strategies, pelvic floor muscle training, fluid management- all tools that can be learned in the Institute’s Pelvic Floor Level 1 course. These behavioral therapies may also be combined with medication prescription, according to the guideline.

When medications are prescribed for overactive bladder, oral anti-muscarinics or oral B3-adrenergic agonists may be prescribed. Although these drugs may help to relax smooth muscles in the bladder wall, the side effects are often strong enough to make the medication difficult to tolerate. Side effects of constipation and dry mouth can occur, and when they do, patients should communicate that to their physician so that the medication dosage or class can be evaluated and modified if possible. We know that patients who have constipation tend to have more bladder dysfunction, so patients can get stuck in a vicious cycle.

When medications are prescribed for overactive bladder, oral anti-muscarinics or oral B3-adrenergic agonists may be prescribed. Although these drugs may help to relax smooth muscles in the bladder wall, the side effects are often strong enough to make the medication difficult to tolerate. Side effects of constipation and dry mouth can occur, and when they do, patients should communicate that to their physician so that the medication dosage or class can be evaluated and modified if possible. We know that patients who have constipation tend to have more bladder dysfunction, so patients can get stuck in a vicious cycle.

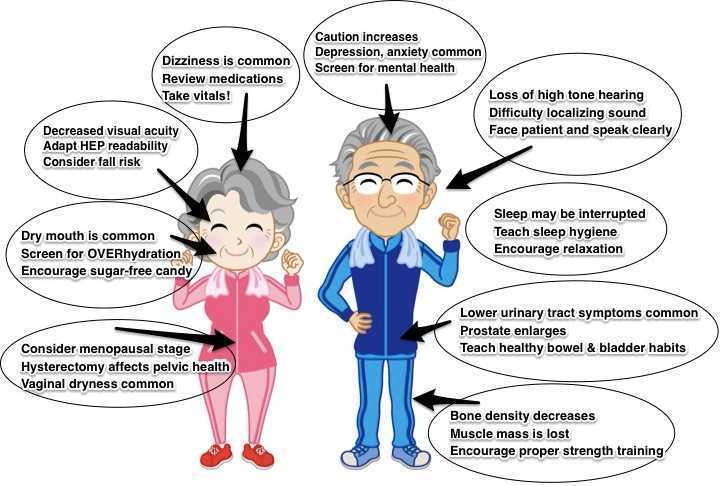

Although patients and their medications are screened at their prescriber’s office and often at the pharmacy, it is important to remember that therapists are an important part of this safety mechanism. Patients may not be candidates for anti-muscarinics if they have narrow angle glaucoma, impaired gastric emptying, or a history of urinary retention. When patients are taking other medications with anticholinergic properties, or are considered frail, adverse drug reactions can also occur. Our geriatric patients may have some additional considerations, not just in medication screening, but also in evaluation and intervention. If you are interested in learning more about pelvic rehabilitation for those in the geriatric population, check out our new continuing education course, Geriatric Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation with Heather S. Rader, PT, DPT, BCB-PMD. The next opportunity to take the class is January 16-17, 2016 in Tampa.

Can patients benefit from a non-face-to-face treatment program for stress urinary incontinence? A recent study addressing this question was published in the British Journal of Urology International. This randomized, controlled trial utilized online recruitment of 250 community-dwelling women ages 18-70 years. Criteria was stress urinary incontinence (SUI) at least 1x/week, diagnosis based on self-assessment questionnaires, 2 days of bladder diaries, as well as a telephone interview with a urotherapist. The Outcomes tools included the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Short Form (ISIC-UI SF), the Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life (ICIQ-LUTSqol), the Patient Global Impression of Improvement, health-specific quality of life (EQ-VAS), use if incontinence aids, and satisfaction with treatment.

The participants were randomized into 2 pelvic floor muscle training groups: an “internet-based” group (n=124) and a group who were sent information in the mail (n=126). The internet-based program contained information about pelvic muscle contractions (8 escalating levels of training), behavioral training related to lifestyle changes. The internet group received email support from the urotherapist, and the postal group did not. Pelvic floor muscle training was instructed at at least 8 contractions 3 times/day. After the 3 month training period, the internet-based treatment group was advised to continue pelvic floor muscle training 2-3 times/week, whereas the mail training group were not given any advice about continued training frequency. Follow-up data was collected at 4 months post-intervention, at 1 year and 2 years. At 2 years follow-up, 38% of the participants were lost from the study.

The participants were randomized into 2 pelvic floor muscle training groups: an “internet-based” group (n=124) and a group who were sent information in the mail (n=126). The internet-based program contained information about pelvic muscle contractions (8 escalating levels of training), behavioral training related to lifestyle changes. The internet group received email support from the urotherapist, and the postal group did not. Pelvic floor muscle training was instructed at at least 8 contractions 3 times/day. After the 3 month training period, the internet-based treatment group was advised to continue pelvic floor muscle training 2-3 times/week, whereas the mail training group were not given any advice about continued training frequency. Follow-up data was collected at 4 months post-intervention, at 1 year and 2 years. At 2 years follow-up, 38% of the participants were lost from the study.

Within both groups, the authors report that the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Short Form (ISIC-UI SF) and the Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life (ICIQ-LUTSqol) showed “highly significant improvements” after 1 and 2 years compared to baseline data. Much of the improvement occurred within the first 4 months of the study “…and then persisted throughout the follow-up period.” When comparing the internet group to the mail-only group, the perception of improvement following treatment was higher. Approximately 2/3 of the women in both groups reported satisfaction with the treatment even at the 2 year follow-up. The authors conclude that the internet or mail-based exercise programs may “…have the potential to increase access to care and the quality of care given to women with SUI [stress urinary incontinence] in a sustainable way.” Additionally, not all patients will improve significantly unless they have one-on-one intervention, leaving plenty of patients who do need our direct care.

If you would like to learn more about exercise prescription for urinary incontinence, consider attending one of Herman & Wallace's many continuing education courses.