When I mentioned to a patient I was writing a blog on yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), she poured out her story to me. Her ex-husband had been abusive, first verbally and emotionally, and then came the day he shook her. Violently. She considered taking her own life in the dark days that followed. Yoga, particularly the meditation aspect, as well as other counseling, brought her to a better place over time. Decades later, she is happily married and has practiced yoga faithfully ever since. Sometimes a therapy’s anecdotal evidence is so powerful academic research is merely icing on the cake.

This study by Walker and Pacik (2017) included 3 voluntary participants: a 75 and a 72 year old male veteran and a 57 year old female veteran, all whom were experiencing a varying cluster of PTSD symptoms for longer than 6 months. Pre- and post-course scores were evaluated from the PTSD Checklist (a 20-item self-reported checklist), the Military Version (PCL-M). All the participants reported decreased symptoms of PTSD after the 5 day training course. The PCL-M scores were reduced in all 3 participants, particularly in the avoidance and increased arousal categories. Even the participant with the most severe symptoms showed impressive improvement. These authors concluded Sudarshan Kriya (SKY) seemed to decrease the symptoms of PTSD in 3 military veterans.

Cushing et al., (2018) recently published online a study testing the impact of yoga on post-9/11 veterans diagnosed with PTSD. The participants were >18 years old and scored at least 30 on the PTSD Checklist-Military version (PCL-M). They participated in weekly 60-minute yoga sessions for 6 weeks including Vinyasa-style yoga and a trauma-sensitive, military-culture based approach taught by a yoga instructor and post-9/11 veteran. Pre- and post-intervention scores were obtained by 18 veterans. Their PTSD symptoms decreased, and statistical and clinical improvements in the PCL-M scores were noted. They also had improved mindfulness scores and decreased insomnia, depression, and anxiety. The authors concluded a trauma-sensitive yoga intervention may be effective for veterans with PTSD symptoms.

Domestic violence, sexual assault, and unimaginable military experiences can all result in PTSD. People in our profession and even more likely, the patients we treat, may live with these horrors in the deepest recesses of their minds. Yoga is gaining acceptance as an adjunctive therapy to improving the symptoms of PTSD. The Trauma Awareness for the Physical Therapist course may assist in shedding light on a dark subject.

Walker, J., & Pacik, D. (2017). Controlled Rhythmic Yogic Breathing as Complementary Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Military Veterans: A Case Series. Medical Acupuncture, 29(4), 232–238.

Cushing, RE, Braun, KL, Alden C-Iayt, SW, Katz ,AR. (2018). Military-Tailored Yoga for Veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Military Medicine. doi:org/10.1093/milmed/usx071

As practitioners, we understand the value of a yoga practice for multiple systems. Yoga improves cardiovascular function, pulmonary function, improves flexibility, builds strength, improves balance, and cultivates resiliency. Prenatal yoga is deemed safe and widely practiced. Beyond not laying prone after the first trimester, what are modifications for practicing yoga while pregnant? Is there any evidence to demonstrate if specific yoga postures are safe from both the maternal and fetal perspective?

Polis et al set out to determine the safety of specific yoga postures using vital signs, pulse oximetry, tacometry, and fetal heart rate monitoring. The patients were diverse in age, race, BMI, gestational age, parity, and yoga experience. Exclusionary criteria included preeclampsia, placenta previa, bleeding in the 2nd or 3rd trimester, gestational diabetes, BMI greater than 35 and other medical conditions that presented contraindications.

Polis et al set out to determine the safety of specific yoga postures using vital signs, pulse oximetry, tacometry, and fetal heart rate monitoring. The patients were diverse in age, race, BMI, gestational age, parity, and yoga experience. Exclusionary criteria included preeclampsia, placenta previa, bleeding in the 2nd or 3rd trimester, gestational diabetes, BMI greater than 35 and other medical conditions that presented contraindications.

The maternal and fetal responses were tested in 26 yoga postures. The selected postures, much like most yoga classes, offered a variety of physical positions. The standing, seated, twists and balancing postures chosen were: Easy Pose, Seated Forward Bend, Cat Pose, Cow Pose, Mountain Pose, Warrior 1, Standing Forward Bend, Warrior 2, Chair Pose, Extended Side Angle Pose, Extended Triangle Pose, Warrior 3, Upward Salute, Tree Pose, Garland Pose, Eagle Pose, Downward Facing Dog, Child’s Pose, Half Moon Pose, Bound Angle Pose, Hero Pose, Camel Pose, Legs up the Wall Pose, Happy Baby Pose, Lord of the Fishes Pose and Corpse Pose.

Balancing postures were modified to decrease fall risk. Warrior 3, Tree Pose, Eagle Pose, and Half Moon Pose were performed at the wall or using a chair for support. The addition of a yoga block to bring the floor closer to the practitioner was used for Extended Side Angle Pose, Extended Triangle Pose, and Garland Pose.

Four poses that have previously been theorized to be contraindicated were studied in this group. These postures are Child’s Pose, Corpse Pose, Downward Facing Dog, and Happy Baby. No adverse reactions were discovered for this specific population during the intervention or in the 24 hour follow-up as reported by email.

Now that we have this data, what do we do with it?

We have the opportunity to educate our non-high-risk patients that the previously theorized contraindicated postures listed above were safe for the self-selected group in this study. Those who are in high-risk categories should understand that even though yoga is not a high impact activity, there should be clearance from the OB team to ensure expectant mothers are moving as safely as possible. With proper guidance, yoga is a safe form of exercise and stress reduction which can optimize physical and mental health during the prenatal period and prepare for birth.

Dustienne Miller is the author and instructor of Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Join her in Kansas City, MO on April 7, 2018 - April 8, 2018 to learn about treating interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, vulvar pain, coccydynia, hip pain, and pudendal neuralgia with a yoga approach.

Polis RL, Gussman D, Kuo YH. Yoga in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:1237–41

You have been treating a highly motivated 24-year-old woman with a diagnosis of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome (IC/BPS). The plan of care includes all styles of manual therapy, including joint mobilization, soft tissue mobilization, visceral mobilization, and strain counterstrain. You utilize neuromuscular reeducation techniques like postural training, breath work, PNF patterns, and body mechanics. Your therapeutic exercise prescription includes mobilizing what needs to move and strengthening what needs to stabilize. Your patient is feeling somewhat better, but you know she has the ability to feel even more at ease in their day to day. Is there anything else left in the rehab tool box to use?

Kanter et al. set out to discover if mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) was a helpful treatment modality for (IC/BPS). The authors were interested in both the efficacy of a treatment centered on stress reduction and the feasibility of women adopting this holistic option.

Kanter et al. set out to discover if mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) was a helpful treatment modality for (IC/BPS). The authors were interested in both the efficacy of a treatment centered on stress reduction and the feasibility of women adopting this holistic option.

The American Urological Association defined first-line treatments for IC/PBS to include relaxation/stress management, pain management and self-care/behavioral modification. Second-line treatment is pelvic health rehab and medications. The recruited patients had to be concurrently receiving first- and second-line treatments, and not further down the treatment cascade like cystoscopies and Botox.

The control group (N=11) received the usual care (as described above in first- and second-line treatments). The intervention group (N=9) received the usual care plus enrollment in an 8-week MBSR course based on the work of Jon Kabat- Zinn. The weekly course was two hours in the classroom supplemented with a 4-CD guide and book for home meditation practice carryover. The course content included meditation, yoga postures, and additional relaxation techniques.

The patients who participated in the MBSR program reported improved symptoms post-treatment, and perhaps more notably, their pain self-efficacy score (PSEQ) significantly improved. All but one of the participants reported feeling “more empowered” to control their bladder symptoms.

As clinicians working so intimately with our patients, we are often given the privilege of bearing witness to the emotional pain of healing chronic, persistent pelvic pain. We understand how terribly frightening it is for our patients to feel like they will never get better and we see this come out sometimes as fear-avoidance, which has the potential to cascade further into other areas of the social sphere.

If we are able to encourage holistic methods of building strategies to handle the challenges of IC/BPS, our patients will be set up for success in ways beyond the treatment room. While we hope for immediate results in the form of pain relief (which five patients in the study did), we also can appreciate the strategy building for resiliency in the face of persistent pain. As a very strong woman said, “hope serves us best when we do not attach specific outcomes to it”.

Dustienne Miller is the author and instructor of Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Join her in Manchester, NH on September 7-8, 2019 or in Buffalo, NY on October 5-6, 2019 to learn about treating interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, vulvar pain, coccydynia, hip pain, and pudendal neuralgia with a yoga approach.

Kanter G, Kommest YM, Qaeda F, Jeppson PC, Dunivan GC, Cichowski, SB, and Rogers RG. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction as a Novel Treatment for Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2016 Nov; 27(11): 1705–1711.

I work at University of Chicago and we are in the throes of preparing for a (big T) Trauma Center. But I am physical therapist who works with (little t) traumatized patients- as I treat only pelvic or oncology patients (and usually both).

From the online dictionary: Trauma is 1. A deeply distressing or disturbing experience (little t trauma) or 2. Physical injury (injury, damage, wound) yes- big T Trauma. In my experience, the Trauma creates the trauma and the body responds in characteristically uncharacteristic ways (more on this later).

People in distress/trauma-affected do not respond rationally or characteristically, so I have learned to respond to distress/trauma in a rational, ethical, legal and caring manner. Always. Every time. To the best of my ability, and without shame or blame.

People in distress/trauma-affected do not respond rationally or characteristically, so I have learned to respond to distress/trauma in a rational, ethical, legal and caring manner. Always. Every time. To the best of my ability, and without shame or blame.

Let’s talk briefly about Trauma Informed Approach

This is a (person), program, institution or system that:

- Realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery

- Recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff and others affected

- Responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures and practices

- Seeks to actively resist retraumatization

The Tenets of Trauma Informed Approach

- Safety

- Trustworthiness and transparency

- Peer support

- Collaboration and mutuality

- Empowerment, voice and choice

- Cultural, historical and gender issues

Trauma Specific Interventions

- Survivors need to be respected, informed, supported, connected, and hopeful- in their recovery

- Interrelation between trauma and symptoms of trauma such as substance abuse, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, musculoskeletal presentation, and acute crisis- including suicidal/homicidal ideations (coordination with other service providers)

- Work in a collaborative way with survivors, families and friends of survivor, and other service providers in a way that will empower survivors

Types of trauma are varied but I usually treat survivors of emotional, verbal, sexual and medical trauma. I have even treated patients who felt traumatized by other pelvic floor physical therapists (again, no judgement). Since most of my clinical experience include sexual and medical trauma survivorship, I try to reframe these experiences as potential Post Traumatic Growth, especially when working with my oncology patients. For my pelvic patients who divulge sexual trauma, I don’t dictate or name anything. I allow the survivor to make the rules and definitions. Survivors of sexual trauma need extra care when treating pelvic floor dysfunction.

First, when treating survivors of sexual trauma: expect ‘characteristically uncharacteristic’ events to occur. These include the psychological/somatic effects of passing out, flashbacks, seizures, tremors, dissociation and other mechanisms of coping with the trauma. Have a plan ready for these patients.

Triaging the survivor to assess their needs, when trauma has been verbalized/disclosed:

- Are you safe right now?

- Do you need medical treatment right now?

- What do you need to feel in control of (PT session/immediately after disclosure of trauma)?

- You have choices in your treatment and in your response to trauma.

- I believe you.

- Lastly, is this a situation for mandated reporting?

After assisting the survivor in their journey towards healing, it is imperative that you take care of yourself. Making healthy boundaries (with patients and others), taking time to decompress, creating healthy ritualistic behaviors, mindfulness/relaxation and somatic release (like yoga, massage or working out) is crucial to successfully treating patients who have experienced trauma and who have shared that trauma experience with you.

Because I use gentle yoga for both my trauma survivors’ treatment and for my own self-care, my new course implements evidenced based trauma sensitive yoga. Additionally, modifications for manual therapy are explored. The class is designed to be informative and experiential while integrating the Trauma Informed Approaches of Safety, Trustworthiness and transparency, Peer support, Collaboration and mutuality, Empowerment, voice and choice and Cultural, historical and gender issues.

Join me in Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist, next available this March in Albany, NY.

Examples of pranayama

Ujjayi

Letting Go Breath

Integrating into the clinic

1) Iyengar BKS. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Schocken; 1995.

2) Sapsford RR, Richardson CA, Maher CF, Hodges PW. Pelvic floor muscle activity in different sitting postures in continent and incontinent women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(9):1741-1747.15.

3) Julie Wiebe, Physical Therapist | Educator, Advocate, Clinician. 2015; http://www.juliewiebept.

4) Talasz H, Kremser C, Kofler M, Kalchschmid E, Lechleitner M, Rudisch A. Phase-locked parallel movement of diaphragm and pelvic floor during breathing and coughing-a dynamic MRI investigation in healthy females. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(1):61-68.

5) Sapsford R. Rehabilitation of pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. Man Ther. 2004;9(1):3-12.

6) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

7) Massery M. THE LINDA CRANE MEMORIAL LECTURE: The Patient Puzzle: Piecing it Together. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2009;20(2):19-27.

8) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

Speaking with a runner friend the other day, I mentioned I was writing a blog on yoga for pelvic pain. She had the same reaction many runners do, stating she has doesn’t care for yoga, she never feels like she is tight, and she would hate being in one position for so long. Ironically, neither of us has taken a yoga class, so any preconceived ideas about it are null and void. I told her yoga is being researched for beneficial health effects, and one day we just might find ourselves in a class together!

Saxena et al.2017 published a study on the effects of yoga on pain and quality of life in women with chronic pelvic pain. The randomized case controlled study involved 60 female patients, ages 18-45, who presented with chronic pelvic pain. They were randomly divided into two groups of 30 women. Group I received 8 weeks of treatment only with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDS). Group II received 1 hour, 5 days per week, for 8 weeks of yoga therapy (asanas, pranayama, and relaxation) in addition to NSAIDS (as needed). Table 1 in the article outlines the exact protocol of yoga in which Group II participated. The subjects were assessed pre- and post-treatment with pain scores via visual analog scale score and quality of life with the World Health Organization quality of life-BREF questionnaire. In the final analysis, Group II showed a statistically significant positive difference pre and post treatment as well as in comparison to Group I in both categories. The authors concluded yoga to be an effective adjunct therapy for patients with chronic pelvic pain and an effective option over NSAIDS for pain.

Saxena et al.2017 published a study on the effects of yoga on pain and quality of life in women with chronic pelvic pain. The randomized case controlled study involved 60 female patients, ages 18-45, who presented with chronic pelvic pain. They were randomly divided into two groups of 30 women. Group I received 8 weeks of treatment only with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDS). Group II received 1 hour, 5 days per week, for 8 weeks of yoga therapy (asanas, pranayama, and relaxation) in addition to NSAIDS (as needed). Table 1 in the article outlines the exact protocol of yoga in which Group II participated. The subjects were assessed pre- and post-treatment with pain scores via visual analog scale score and quality of life with the World Health Organization quality of life-BREF questionnaire. In the final analysis, Group II showed a statistically significant positive difference pre and post treatment as well as in comparison to Group I in both categories. The authors concluded yoga to be an effective adjunct therapy for patients with chronic pelvic pain and an effective option over NSAIDS for pain.

In the Pain Medicine journal, Huang et al.2017 presented a single-arm trial attempting to study the effects of a group-based therapeutic yoga program for women with chronic pelvic pain (CPP), focusing on severity of pain, sexual function, and overall well-being. The comprehensive program was created by a group of women’s health researchers, gynecological and obstetrical medical practitioners, yoga consultants, and integrative medicine clinicians. Sixteen women with severe pelvic pain of at least 6 months’ duration were recruited. The group yoga classes focused on lyengar-based techniques, and the subjects participated in group classes twice a week and home practice 1 hour per week for 6 weeks. The Impact of Pelvic Pain (IPP) questionnaire assessed how the participants’ pain affected their daily life activities, emotional well-being, and sexual function. Sexual Health Outcomes in Women Questionairre (SHOW-Q) offered insight to sexual function. Daily logs recorded the women’s self-rated pelvic pain severity. The results showed the average pain severity improved 32% after the 6 weeks, and IPP scores improved for daily living (from 1.8 to 0.9), emotional well-being (from 1.7 to 0.9), and sexual function (from 1.9 to 1.0). The SHOW-Q "pelvic problem interference" scale also improved from 53 to 23. The multidisciplinary panel concluded they found preliminary evidence that teaching yoga to women with CPP is feasible for pain management and improvement of quality of life and sexual function.

Whatever treatment we provide for our patients, we need to consider the individual and their often biased opinions or perceptions. Providing research and educating each patient on the efficacy behind the proposed therapy will likely impact their outcome. The Yoga for Pelvic Pain course can enhance a clinician’s understanding and allow them to better implement a potentially life-changing therapy for their clients.

Saxena, R., Gupta, M., Shankar, N., Jain, S., & Saxena, A. (2017). Effects of yogic intervention on pain scores and quality of life in females with chronic pelvic pain. International Journal of Yoga, 10(1), 9–15. http://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.186155

Huang, AJ, Rowen, TS, Abercrombie, P, Subak, LL, Schembri, M, Plaut, T, & Chao, MT. (2017). Development and Feasibility of a Group-Based Therapeutic Yoga Program for Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Pain Medicine. http://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw306

During labor, I had no problem breathing out. My hang up came when I had to inhale - actually oxygenate my blood and maintain a healthy heart rate for my almost newborn baby. When extra staff filled the delivery room, and an oxygen mask was placed over my face, my husband remained calm but later told me how freaked out he was. He was watching the monitors that showed a drop in my vitals as well as our baby’s. In retrospect, I wonder if practicing yoga, particularly the breathing techniques involved with pranayama practice, could have prevented that moment.

A research article by Critchley et al., (2015) broke down breathing to a very scientific level, determining the consequences of slow breathing (6 breaths/minute) versus induced hypoxic challenges (13% inspired O2) on the cardiac and respiratory systems and their central neural substrates. Functional magnetic resonance imaging measured the 20 healthy subjects’ specific brain activity during the slow and normal rate breathing. The authors mentioned the controlled slow breathing of 6 breaths/minute is the rate encouraged during yoga practice. This rate decreases sympathetic activity, lessening vasoconstriction associated with hypertension, and it prevents physiological stress from affecting the cardiovascular system. Each part of the brain showed responses to the 2 conditions, and the general conclusion was modifying breathing rate impacted autonomic activity and improved both cardiovascular and psychological health.

A research article by Critchley et al., (2015) broke down breathing to a very scientific level, determining the consequences of slow breathing (6 breaths/minute) versus induced hypoxic challenges (13% inspired O2) on the cardiac and respiratory systems and their central neural substrates. Functional magnetic resonance imaging measured the 20 healthy subjects’ specific brain activity during the slow and normal rate breathing. The authors mentioned the controlled slow breathing of 6 breaths/minute is the rate encouraged during yoga practice. This rate decreases sympathetic activity, lessening vasoconstriction associated with hypertension, and it prevents physiological stress from affecting the cardiovascular system. Each part of the brain showed responses to the 2 conditions, and the general conclusion was modifying breathing rate impacted autonomic activity and improved both cardiovascular and psychological health.

Vinay, Venkatesh, and Ambarish (2016) presented a study on the effect of 1 month of yoga practice on heart rate variability in 32 males who completed the protocol. The authors reported yoga is supposed to alter the autonomic system and promote improvements in cardiovascular health. Not just the breathing but also the movements and meditation positively affect mental health and general well-being. The subjects participated in 1 hour of yoga daily for 1 month, and at the end of the study, the 1 bpm improvement in heart rate was not statistically significant. However, heart rate variability measures indicated a positive shift of the autonomic system from sympathetic activity to parasympathetic, which reduces cortisol levels, improves blood pressure, and increases circulation to the intestines.

Bershadsky et al., (2014) studied the effect of prenatal Hatha yoga on cortisol levels, affect and depression in the 34 women who completed pre, mid, and post pregnancy saliva tests and questionnaires. While levels of cortisol increase naturally with pregnancy, yoga was found to minimize the mean levels compared to the days the subjects did not participate in yoga. After a single 90-minute yoga session, during which breathing was emphasized throughout the session, women had higher positive affect; but, the cortisol level was not significantly different from the control group. Overall, the authors concluded yoga had potential to minimize depression and cortisol levels in pregnancy.

Considering the positive effect of slow breathing practiced in yoga, the positive shift in the autonomic nervous system function and the decrease in cortisol levels, yoga is gaining credibility as an effective adjunct to treatment during pregnancy. If a woman enters the delivery room with a solid practice of slow breathing under her belt, she may be equipped to handle the intensity of contractions and the pain of pushing a little better. Yoga may help a woman breathe for her life and her baby’s as well.

If you're interested in learning more about yoga for pregnant patients, consider attending Yoga as Medicine for Pregnancy with Ginger Garner, PT, DPT, ATC/LAT, PYT. The next opportunity is in Fort Lauderdale, FL on January 28th and 29th, 2017. Don't miss out!

Critchley, H. D., Nicotra, A., Chiesa, P. A., Nagai, Y., Gray, M. A., Minati, L., & Bernardi, L. (2015). Slow Breathing and Hypoxic Challenge: Cardiorespiratory Consequences and Their Central Neural Substrates. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0127082.

Vinay, A., Venkatesh, D., & Ambarish, V. (2016). Impact of short-term practice of yoga on heart rate variability. International Journal of Yoga, 9(1), 62–66.

Bershadsky, S., Trumpfheller, L., Kimble, H. B., Pipaloff, D., & Yim, I. S. (2014). The effect of prenatal Hatha yoga on affect, cortisol and depressive symptoms. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 20(2), 106–113.

Urinary incontinence (UI) can be problematic for both men and women, however, is more prevalent in women. Incontinence can contribute to poor quality of life for multiple reasons including psychological distress from stigma, isolation, and failure to seek treatment. Patients enduring incontinence often have chronic fear of leakage in public and anxiety about their condition. There are two main types of urinary leakage, stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urge urinary incontinence (UUI).

SUI is involuntary loss of urine with physical exertion such as coughing, sneezing, and laughing. UUI is a form of incontinence in which there is a sudden and strong need to urinate, and leakage occurs, commonly referred to as “overactive bladder”. Currently, SUI is treated effectively with physical therapy and/or surgery. Due to underlying etiology, UUI however, can be more difficult to treat than SUI. Often, physical therapy consisting of pelvic floor muscle training can help, however, women with UUI may require behavioral retraining and techniques to relax and suppress bladder urgency symptoms. Commonly, UUI is treated with medication. Unfortunately, medications can have multiple adverse effects and tend to have decreasing efficacy over time. Therefore, there is a need for additional modes of treatment for patients suffering from UUI other than mainstream medications.

An interesting article published in The Journal of Alternative and Complimentary Medicine reviews the potential benefits of yoga to improve the quality of life in women with UUI. The article details proposed concepts to support yoga as a biobehavioral approach for self-management and stress reduction for patients suffering with UUI. The article proposes that inflammation contributes to UUI symptoms and that yoga can help to reduce inflammation.

Surfacing evidence indicates that inflammation localized to the bladder, as well as low-grade systemic inflammation, can contribute to symptoms of UUI. Research shows that women with UUI have higher levels of serum C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation), as well as increased levels of inflammatory biomarkers (such as interleukin-6). Additionally, when compared to asymptomatic women and women with urgency without incontinence, patients with UUI have low-grade systemic inflammation. It is hypothesized that the inflammation sensitizes bladder afferent nerves through recruitment of lower threshold and typically silent C fiber afferents (instead of normally recruited, higher threshold A-delta fibers, that respond to stretch of the bladder wall and mediate bladder fullness and normal micturition reflexes). Therefore, reducing activation threshold for bladder sensory afferents and a lower volume threshold for voiding, leading to the UUI.

How can yoga help?

Yoga can reduce levels of inflammatory mediators. According to the article, recent research has shown that yoga can reduce inflammatory biomarkers (such as interleukin -6) and C-reactive protein. Decreasing inflammatory mediators within the bladder may reduce sensitivity of C fiber afferents and restore a more normalized bladder sensory nerve threshold.

Studies suggest that women with UUI have an imbalance of their autonomic nervous system. The posture, breathing, and meditation completed with yoga practice may improve autonomic nervous system balance by reducing sympathetic activity (“fight or flight”) and increasing parasympathetic activity (“rest and digest”).

The discussed article highlights yoga as a logical, self-management treatment option for women with UUI symptoms. Yoga can help to manage inflammatory symptoms that directly contribute to UUI by reducing inflammation and restoring autonomic nervous system balance. Additionally, regular yoga practice can improve general well-being, breathing patterns, and positive thinking, which can reduce overall stress. Yoga provides general physical exercise that improves muscle tone, flexibility, and proprioception. Yoga can also help improve pelvic floor muscle coordination and strength which can be helpful for UUI. Yoga seems to provide many benefits that could be helpful for a patient with UUI.

In summary, UI remains a common medical problem, in particular, in women. While SUI is effectively treated with both conservative physical therapy and surgery, long-term prescribed medication remains the treatment modality of choice for UUI. However, increasing evidence, including that described in this article, suggests that alternative conservative approaches, such as yoga and exercise, may serve as a valuable adjunct to traditional medical therapy.

Tenfelde, S., & Janusek, L. W. (2014). Yoga: a biobehavioral approach to reduce symptom distress in women with urge urinary incontinence. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20(10), 737-742.

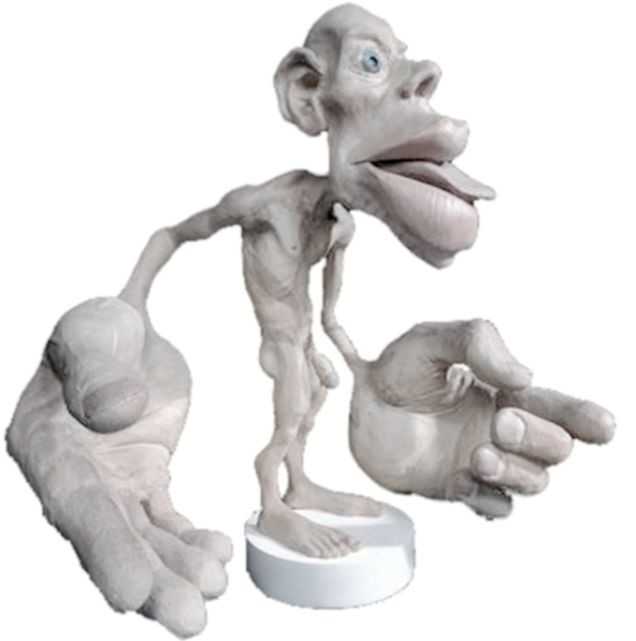

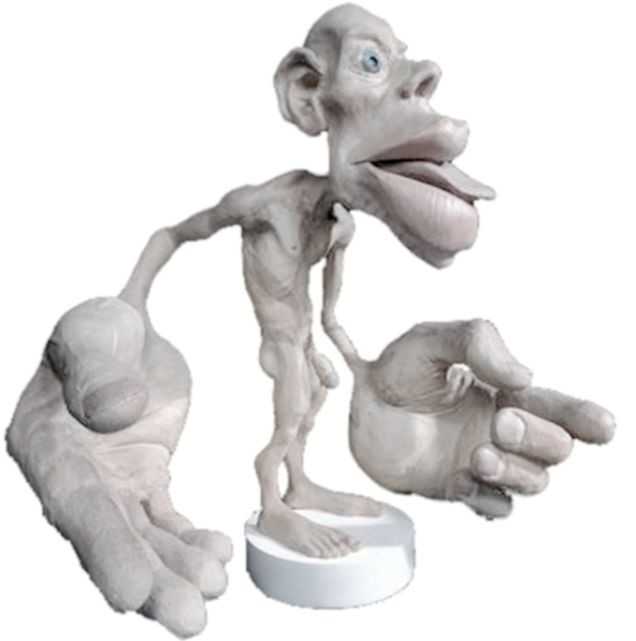

In the 16th century, a theory called Preformationism claimed that sperm contained a preformed, exceedingly minute body referred to as a homunculus, which eventually became a person. This idea of a tiny man had staying power, as today the homunculus is a “body map” based on how much of the cerebral cortex is devoted to sensing each part of the body. Although the idea of a 16th alchemist placing little bodies into a flask conjures a variety of tantalizing images, our program focuses on the mundane, contemporary version of the homunculus. So…what does this have to do with a course that addresses pelvic floor dysfunction? Everything.

Emerging evidence indicates that therapies that include work to enhance body awareness/kinesthetic sense are potent and effective. Our professional training unfortunately, tends to over-emphasize a structural approach. The good news is that manual therapy, to some degree, enhances a client’s body awareness; but when we have more “tools” to capitalize on this synergy between manual therapy and improved body awareness, we have a potent “elixir” to promote change. To quote Deane Juhan, “touching hands are not like pharmaceuticals or scalpels…they are like flashlights in a darkened room.” By using the “flashlight”, we not only contribute to structural change, but neurological change – meaning the more we pay attention to a particular part of our body, the more “real estate” the brain devotes to that part of the body. Increasing the pelvic floor’s “footprint” on the brain can enhance function of the pelvic floor dramatically and quickly. Therefore, rehabilitation to address pelvic floor dysfunction benefits from weaving orthopedic, neurologic and mindfulness practices together.

Emerging evidence indicates that therapies that include work to enhance body awareness/kinesthetic sense are potent and effective. Our professional training unfortunately, tends to over-emphasize a structural approach. The good news is that manual therapy, to some degree, enhances a client’s body awareness; but when we have more “tools” to capitalize on this synergy between manual therapy and improved body awareness, we have a potent “elixir” to promote change. To quote Deane Juhan, “touching hands are not like pharmaceuticals or scalpels…they are like flashlights in a darkened room.” By using the “flashlight”, we not only contribute to structural change, but neurological change – meaning the more we pay attention to a particular part of our body, the more “real estate” the brain devotes to that part of the body. Increasing the pelvic floor’s “footprint” on the brain can enhance function of the pelvic floor dramatically and quickly. Therefore, rehabilitation to address pelvic floor dysfunction benefits from weaving orthopedic, neurologic and mindfulness practices together.

This program is designed to add a new dimension for the skilled pelvic floor practitioner and to also serve practitioners new to this area of practice. There is no internal manual work; rather we draw from our deep knowledge of Yoga, Tai Chi, along with other Chinese internal martial arts (that put lots of emphasis on the pelvic floor for performance) and Feldenkrais to address pelvic floor dysfunction. Some lessons focus directly on the pelvic region and others on integrating the pelvic floor with full body movement. Ultimately, our goal is to help you connect the dots between structural, functional movement and mindfulness practices, as this powerful triad offers practitioners a comprehensive, approach for treating pelvic floor dysfunction.

We hope you’ll come join in New York City on September 18th & 19th. If you do, wear comfortable clothes as the workshop is designed to provide participants opportunities to embody the work…emphasis is placed on labs more than lecture.

Don’t hesitate to contact us if you have any questions.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

In manual therapy training, we do not learn just one position to mobilize a joint, so why should pelvic floor muscle training be limited by the standard training methods? There is almost always at least one patient in the clinic that fails to respond to the “normal” treatment and requires a twist on conventional therapy to get over a dysfunction. Thankfully, classes like “Integrative Techniques for Pelvic Floor and Core Function” provide clinicians with the extra tools that might help even just one patient with lingering symptoms.

In 2014, Tenfelde and Janusek considered yoga as a treatment for urge urinary incontinence in women, referring to it as a “biobehavioral approach.” The article reviews the benefits of yoga as it relates to improving the quality of life of women with urge urinary incontinence. Yoga may improve sympatho-vagal balance, which would lower inflammation and possibly psychological stress; therefore, the authors suggested yoga can reduce the severity and distress of urge UI symptoms and their effect on daily living. Since patho-physiologic inflammation within the bladder is commonly found, being able to minimize that inflammation through yoga techniques that activate the efferent vagus nerve (which releases acetylcholine) could help decrease urge UI symptoms. The breathing aspect of yoga can reduce UI symptoms as it modulates neuro-endocrine stress response symptoms, thus reducing activation of psychological and physiologic stress and inflammation associated with stress. The authors concluded the mind-body approach of yoga still requires systematic evaluation regarding its effect on pelvic floor dysfunction but offers a promising method for affecting inflammatory pathways.

In 2014, Tenfelde and Janusek considered yoga as a treatment for urge urinary incontinence in women, referring to it as a “biobehavioral approach.” The article reviews the benefits of yoga as it relates to improving the quality of life of women with urge urinary incontinence. Yoga may improve sympatho-vagal balance, which would lower inflammation and possibly psychological stress; therefore, the authors suggested yoga can reduce the severity and distress of urge UI symptoms and their effect on daily living. Since patho-physiologic inflammation within the bladder is commonly found, being able to minimize that inflammation through yoga techniques that activate the efferent vagus nerve (which releases acetylcholine) could help decrease urge UI symptoms. The breathing aspect of yoga can reduce UI symptoms as it modulates neuro-endocrine stress response symptoms, thus reducing activation of psychological and physiologic stress and inflammation associated with stress. The authors concluded the mind-body approach of yoga still requires systematic evaluation regarding its effect on pelvic floor dysfunction but offers a promising method for affecting inflammatory pathways.

Pang and Ali (2015) focused on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments for interstitial cystitis (IC) and bladder pain syndrome (BPS). Since conventional therapy has not been definitely determined for the IC/BPS population, CAM has been increasingly used as an optional treatment. Two of the treatments under the CAM umbrella include yoga (mind-body therapy) and Qigong (an energy therapy). Yoga can contribute to IC/BPS symptom relief via mechanisms that relax the pelvic floor muscle. Actual yoga poses of benefit include frog pose, fish pose, half-shoulder stand and alternate nostril breathing. According to a systematic review, Qigong and Tai Chi can improve function, immunity, stress, and quality of life. Qigong has been effective in managing chronic pain, although not specifically evidenced with IC/BPS groups. Qigong has also been shown to reduce stress and anxiety and activate the brain region that suppresses pain. The CAM gives a multimodal approach for treating IC/BPS, and this has been recommended by the International Consultation on Incontinence Research Society.

Evidence is emerging in every area of treatment these days, so it is only a matter of time before randomized controlled trials regarding alternative treatment methods for the pelvic floor begin to fill pages of our professional journals. Yoga, Qigong, Tai Chi, biologically based therapies, manipulative and body-based approaches, and whole medical systems all offer safe, effective treatment options for the IC/BPS and urinary incontinence patient populations. The more we use these extra treatment tools and document the results, the more likely we will see clinical trials proving their efficacy.

Tenfelde, S and Janusek, L. (2014). Yoga: A Biobehavioral Approach to Reduce Symptom Distress in Women with Urge Urinary Incontinence. THE JOURNAL OF ALTERNATIVE AND COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE. 20 (10), 737–742. http://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2013.0308

Pang, R., & Ali, A. (2015). The Chinese approach to complementary and alternative medicine treatment for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome.Translational Andrology and Urology, 4(6), 653–661. http://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.08.10