While you may be reading this thinking, ‘I don’t know anyone who is Intersex,’ or ‘I’ve never treated a patient who is Intersex’ you might be surprised to find that 1.7% to 4% of people are Intersex, according to Zeeman and Aranda (2020) in their 2020 article A Systematic Review of the Health and Healthcare Inequalities for People with Intersex Variance.

According to Haghighat, et. al (2023) in their article Intersex people's perspectives on affirming healthcare practices: A qualitative study, “Intersex people have variations in their sex characteristics that do not exclusively fall within binary definitions of male and female.” These variations can be chromosomal, hormonal, gonadal, or anatomical (Cochetti, Monro, Vecchietti, & Yeadon-Lee [2020] and Haghighat, et. al [2023]).

Intersex folx are often seen by multiple healthcare providers throughout their lifetime, including pelvic rehab practitioners. However, one thing that most don’t know, is that historically; Intersex folx have been very mistreated and pathologized by healthcare workers. Many Intersex folx have been given non-medically necessary and non-consensual surgical procedures and hormone treatments over the years; and unfortunately, some of these practices are still occurring around the world even today. Intersex folx have also been treated by providers with inaccurate education and inadequate training needed to provide care to Intersex populations, leaving many patients who are Intersex being the ones who educate their own medical providers about their variations and healthcare needs. Tiffany Jones (2018) also mentions in her article Intersex Studies: A Systematic Review of International Health Literature that even language in the medical literature is inaccurate and inadequate when describing Intersex populations (Jones, 2018).

This maltreatment and poor education on the healthcare providers' part, as well as dissemination of inaccurate and pathologizing medical information; can lead to copious trauma for patients and a lack of trust in healthcare workers and healthcare systems. In Haghighat, et. al.’s article, they state that “depathologization of intersex variations and comprehensive teachings of intersex history and medical care must be incorporated into medical curricula to mitigate experiences of medical trauma and to relieve the burden placed on patients to be their own medical experts and advocates. Systemic change is needed for the normalization and demedicalization of intersex variations and for the medical empowerment of the intersex community.”

In my course Intersex Patients: Rehab and Inclusive Care, next scheduled for November 16, 2024, healthcare providers will learn about the healthcare needs that are unique to Intersex folx and about how to provide trauma-informed, evidence-based evaluations, treatments, and plans of care for patients who are Intersex. Students will also learn how to provide Intersex-Affirming Healthcare and how to be better allies in healthcare and in life to Intersex folx so that we can help put a stop to these non-medically necessary and non-consensual medical procedures, empower patients who are Intersex to have a say in their healthcare practices, to help stop the pathologization and further marginalization of Intersex people, and to educate other people (not just healthcare providers) about how to be allies to Intersex folx everywhere.

Resources:

- Intersex Studies: A Systematic Review of International Health Literature. Jones, T. (2018). Intersex Studies: A Systematic Review of International Health Literature. Sage Open, 8(2).https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017745577

- Intersex people's perspectives on affirming healthcare practices: A qualitative study. Darius Haghighat, Tala Berro, Lillian Torrey Sosa, Kayla Horowitz, Bria Brown-King, Kimberly Zayhowski. Intersex people's perspectives on affirming healthcare practices: A qualitative study. Social Science & Medicine, Vol 329, 2023 116047, ISSN 0277-9536, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116047.

- A Systematic Review of the Health and Healthcare Inequalities for People with Intersex Variance. Zeeman L, Aranda K. A Systematic Review of the Health and Healthcare Inequalities for People with Intersex Variance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Sep 8;17(18):6533. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186533. PMID: 32911732; PMCID: PMC7559554.

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13691058.2020.1825815#abstract/. Cochetti, D., Munro, S., Vecchietti, V., & Yeadon-Lee, T. (2020, November 25). 500-515. doi: 10.1080/13691058.

- Gain foundational knowledge. Not everyone with a healthcare degree arrived there by way of being a biology major. Accordingly, many people in the health field are simply unaware of how many wonderful people in this world exist outside the XY and XX binary. Did you know there are also people with just one X chromosome per cell? Some people are even XXYY or XXY! Also, some people may have chromosomes that fit binary expectations; however, they have generic variations that result in different bodily responses to sex hormones. This might, for example, lead to someone with XY chromosomes presenting with testes in the abdomen while also having breasts and a vulva. By taking this course, you will be able to appreciate the wide range of what it means to be a human. One of my all-time favorite podcast series, Gonads by RadioLab, is a great starting point for engaging with these concepts prior to the course: https://radiolab.org/series/radiolab-presents-gonads/

- Connect with your clients better. After taking this class, I learned new ways to bring up the topic of what it means to be intersex and how that relates to pelvic rehabilitation. I went from not being aware of any of my current clients being intersex, to finding out two were intersex within a few days of completing this course! This class will help you to build better rapport with all of your clients, whether they are intersex or not.

- Get practical tips on making your practice more inclusive. One of the big takeaways for me from this course was how to update my intake forms. I had already accounted for gender differences on my documents, but not sex differences. Through this course, I got great suggestions, such as including an organ inventory, rather than simply the three choices of male/female/intersex. The organ inventory is a great example of making a form more inclusive because I would want to know if a non-intersex (also called endosex) cisgender man didn't have, for instance, testicles just as much as I'd want to be prepared to support an intersex client with variations in anatomical structures. Here is a link to ideas for making your forms more intersex-friendly: https://www.queeringmedicine.com/resources/intake-form-guidance-for-providers.

AUTHOR BIO:

Molly O’Brien-Horn, PT DPT, CLT

Molly O’Brien-Horn graduated from Rutgers School of Biomedical & Health Sciences (formerly the University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey) with her Doctor of Physical Therapy degree. She is a Pelvic Health Physical Therapist, a Certified Lymphedema Therapist, and an LSVT BIG Parkinson’s Disease Certified Therapist. She is also a sex counselor, a trained childbirth doula, and a trained postpartum doula. Molly is a member of the American Physical Therapy Association Academy of Pelvic Health Physical Therapy and is also a Teaching Assistant with the Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

Molly is passionate about providing accessible healthcare to pelvic health patients of all age ranges, all gender-identities, all sexualities, all body variations, and all ability levels. She also has experience in a variety of physical therapy settings over the years including pediatric and adult oncology, school-based pediatrics, inpatient and intensive care unit hospital-based settings, skilled nursing facilities, outpatient and sports-based orthopedics, and wound care.

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in women, following skin cancers. In the United States, 1 in 8 women will develop breast cancer in their lifetime.

The treatments used in breast cancer also affect the pelvic floor.

Survivors report issues with pelvic floor dysfunction including incontinence, pelvic pain, sexual dysfunction, and constipation. Up to 58% of survivors report issues with bladder urgency and incontinence. (1) Around 52% of women report sexual dysfunction six months following post-breast cancer treatment, and 19-26% continue to have sexual dysfunction five to ten years after their diagnosis. (2) When compared to individuals without breast cancer, those with breast cancer presented with significantly weaker pelvic floor muscles when measured by maximal squeeze pressure and digital examination.

Additionally, the ability to relax the pelvic floor was poorer in participants with breast cancer compared to controls. (3) These are problems that pelvic rehabilitation practitioners can assist survivors with. However, not all survivors are being referred to therapy. Barriers to individuals accessing treatment for pelvic floor dysfunction include a lack of awareness about pelvic floor dysfunction following breast cancer treatments and health care professionals “not focusing on the management of pelvic floor symptoms during cancer treatment.” (4<)

We as rehabilitation clinicians should strive to correct this!

We can educate providers and patients regarding the potential to develop pelvic floor dysfunction with breast cancer treatment and how therapy can help.

Learn more about cancer treatment and pelvic-related complications in the Oncology of the Pelvic Floor Series. In the first course, you will learn about general oncology treatment, (certified lymphatic therapists can skip this course). The second course (Oncology of the Pelvic Floor Level 2A) in the series focuses on penile, testicular, and prostate cancer, along with colorectal cancers. The third course (Oncology of the Pelvic Floor Level 2B) in the series focuses on gynecological cancers and bladder cancer. In the series, you will learn about the medical treatment of cancer, how this affects the body, and how rehabilitation clinicians can help patients. Hands-on techniques are learned that can help patients return to activities they love. The first course in the series, Oncology of the Pelvic Floor Level 1, is being offered November 2-3. Join us to learn more about helping individuals with cancer!

Resources:

- Donovan KA, Boyington AR, Ismail-Khan R, Wyman JF. (2012) Urinary Symptoms in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancer. 118(3): 582–593.

- Seav SM, Dominick SA, Stepahyuk B, Gorman JR, Chingos DT, Ehren JL, Krychman ML, Su HL. (2015). Management of sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Women's Midlife Health 1:9.

- Colombage UN, Soh SE, Lin KY, Frawley HC. (2023). Pelvic floor muscle function in women with and without breast cancer: a cross-sectional study. Continence. 5; 100580.

- Colombage UN, Lin KY, Soh SE, Brennen R, Frawley HC. (2022). Experiences of pelvic floor dysfunction and treatment in women with breast cancer: a qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 30; 8139-8149.

AUTHOR BIO:

Allison Ariail, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, BCB-PMD, PRPC

Allison Ariail has been a physical therapist since 1999. She graduated with a BS in physical therapy from the University of Florida and earned a Doctor of Physical Therapy from Boston University in 2007. Also in 2007, Dr. Ariail qualified as a Certified Lymphatic Therapist. She became board-certified by the Lymphology Association of North America in 2011 and board-certified in Biofeedback Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction by the Biofeedback Certification International Alliance in 2012. In 2014, Allison earned her board certification as a Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner. Allison specializes in the treatment of the pelvic ring and back using manual therapy and ultrasound imaging for instruction in a stabilization program. She also specializes in women’s and men’s health including conditions of chronic pelvic pain, bowel and bladder disorders, and coccyx pain. Lastly, Allison has a passion for helping oncology patients, particularly gynecological, urological, and head and neck cancer patients.

Allison Ariail has been a physical therapist since 1999. She graduated with a BS in physical therapy from the University of Florida and earned a Doctor of Physical Therapy from Boston University in 2007. Also in 2007, Dr. Ariail qualified as a Certified Lymphatic Therapist. She became board-certified by the Lymphology Association of North America in 2011 and board-certified in Biofeedback Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction by the Biofeedback Certification International Alliance in 2012. In 2014, Allison earned her board certification as a Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner. Allison specializes in the treatment of the pelvic ring and back using manual therapy and ultrasound imaging for instruction in a stabilization program. She also specializes in women’s and men’s health including conditions of chronic pelvic pain, bowel and bladder disorders, and coccyx pain. Lastly, Allison has a passion for helping oncology patients, particularly gynecological, urological, and head and neck cancer patients.

In 2009, Allison collaborated with the Primal Pictures team for the release of the Pelvic Floor Disorders program. Allison's publications include: “The Use of Transabdominal Ultrasound Imaging in Retraining the Pelvic-Floor Muscles of a Woman Postpartum.” Physical Therapy. Vol. 88, No. 10, October 2008, pp 1208-1217. (PMID: 18772276), “Beyond the Abstract” for Urotoday.com in October 2008, “Posters to Go” from APTA combined section meeting poster presentation in February 2009 and 2013. In 2016, Allison co-authored a chapter in “Healing in Urology: Clinical Guidebook to Herbal and Alternative Therapies.”

Allison works in the Denver metro area in her practice, Inspire Physical Therapy and Wellness, where she works in a more holistic setting than traditional therapy clinics. In addition to instructing Herman and Wallace on pelvic floor-related topics, Allison lectures nationally on lymphedema, cancer-related changes to the pelvic floor, and the sacroiliac joint. Allison serves as a consultant to medical companies, and physicians.

When thinking of the Developmental Sequence (Supine, Side-lying, Prone, Quadruped, Tall Kneeling, Half-kneeling, Standing, and Walking), I used to think of either pediatrics or people with strokes. However, the developmental sequence can be very useful from an orthopedic standpoint specifically with osteoporosis patients.

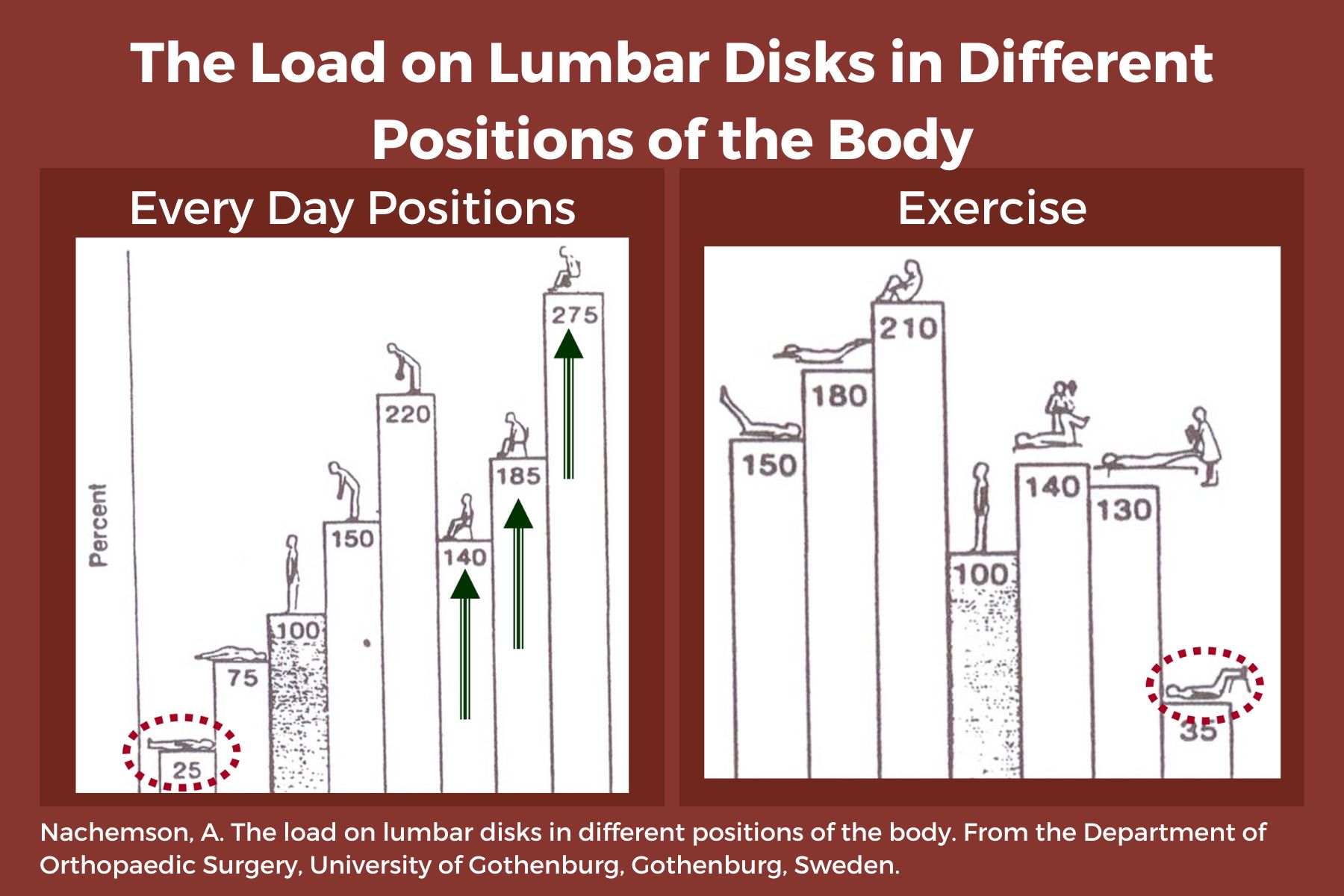

We know that sitting is the most compressive position for our spines, yet repeatedly, I see physical therapists start exercise programs in sitting. There are several reasons I’d like you to consider starting patients in supine.

- Sitting increases intradiscal pressure. (1)

- Supine is a restful position, allowing tense muscles to relax, and can be a great way to reduce anxiety and cortisol running through the body. Ensure that the patient is propped with knees flexed or pillows under the knees, and forearms supported if there is tightness in the biceps.

- Patients can now concentrate on their breath, become aware of any “holding patterns” of tension throughout their body, and free up the mind to focus on learning new skills.

- When we are in higher levels of positioning-sitting, standing, or walking, our brain is focused on survival such as “not falling”. We have many more muscles and joints to control - ankles, knees, hips, etc. This reduces our ability to focus on learning new skills such as engaging the core muscles, relaxing the neck, stop clenching the fingers, etc.

- Preparation is key. We must help our patients gain mastery at one level and then move to the next. Once a patient can understand and find a neutral spine in prone, they are ready to move to side-lying.

- Side-lying can be very beneficial in teaching neutral spine because side-lying is “discombobulating.” We get lost in space and default to the fetal position - a flexed, contra-indicated posture for people with osteoporosis. Use a dowel rod or broom handle to provide feedback from the occiput to the mid-thoracic spine to the sacrum. Have your patient straighten their knees and hips so that, “If you were lying with your back against an imaginary wall, the back of your head, upper back, sacrum, and heels would touch the wall.”

- Prone: Not every osteoporosis patient you see will be able to ultimately transition to prone, but a high majority can and should. Again, propping is critical to allow any anatomical limitations such as shoulder tightness. Use a pillow longitudinally rather than transversely across the abdomen to elevate the shoulders so they can flex to allow the forehead on the hands. If not, keep arms by their side and provide a towel roll under the forehead. This position requires several “stages” of advancement over time and education to engage transversus abdominus, especially for those with spinal stenosis and/or tight hip flexors. The feet should be off the edge of the bed to allow for tightness in plantarflexion.

Working with patients in these three basic positions, while focusing on intercostal breathing, muscle relaxation of the neck, fingers, and other compensatory patterns as we move up the chain, builds a foundation to prepare for functional activities of sit-to-stand, static standing, and movement. These are not stepping stones to be skipped in order to jump into the higher-level functional activities. You would not build a house without a firm foundation. Make sure your patient has the building blocks necessary for the best possible outcomes.

Please join Frank Ciuba and me for our upcoming remote course: Osteoporosis Management: An Introductory Course for Healthcare Professionals on Saturday, Nov 2, 2024. We will discuss osteoporosis-safe exercises, balance and gait activities, and additional ways to help your patients build a strong foundation for movement competence!

Reference:

- Comparison of In Vivo Intradiscal Pressure between Sitting and Standing in Human Lumbar Spine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal ListLife (Basel) PMC8950176 Jia-Qi Li,1 Wai-Hang Kwong,1,* Yuk-Lam Chan,1 and Masato Kawabata2

AUTHOR BIO:

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb is a graduate of Indiana University and a former NCAA athlete where she competed on the IU Gymnastics team. She has always been interested in movement and function and is grateful to combine her skills as a PT and Pilates instructor. She has been certified through Polestar Pilates since 2005, a Certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist through the Meeks Method since 2008, and a Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult through the Geriatric Section of the APTA.

When thinking of the Developmental Sequence (Supine, Side-lying, Prone, Quadruped, Tall Kneeling, Half-kneeling, Standing, and Walking), I used to think of either pediatrics or people with strokes. However, the developmental sequence can be very useful from an orthopedic standpoint specifically with osteoporosis patients.

We know that sitting is the most compressive position for our spines, yet repeatedly, I see physical therapists start exercise programs in sitting. There are several reasons I’d like you to consider starting patients in supine.

- Sitting increases intradiscal pressure. (1)

- It is a restful position, allowing tense muscles to relax, and can be a great way to reduce anxiety and cortisol running through the body. Ensure that the patient is propped with knees flexed or pillows under the knees, and forearms supported if there is tightness in the biceps.

- Patients can now concentrate on their breath, become aware of any “holding patterns” of tension throughout their body, and free up the mind to focus on learning new skills.

- When we are in higher levels of positioning-sitting, standing, or walking, our brain is focused on survival such as “not falling”. We have many more muscles and joints to control - ankles, knees, hips, etc. This reduces our ability to focus on learning new skills such as engaging the core muscles, relaxing the neck, stop clenching the fingers, etc.

- Preparation is key. We must help our patients gain mastery at one level and then move to the next. Once a patient can understand and find a neutral spine in prone, they are ready to move to side-lying.

- Side-lying can be very beneficial in teaching neutral spine because side-lying is “discombobulating.” We get lost in space and default to the fetal position - a flexed, contra-indicated posture for people with osteoporosis. Use a dowel rod or broom handle to provide feedback from the occiput to the mid-thoracic spine to the sacrum. Have your patient straighten their knees and hips so that, “If you were lying with your back against an imaginary wall, the back of your head, upper back, sacrum, and heels would touch the wall.”

- Prone: Not every osteoporosis patient you see will be able to ultimately transition to prone, but a high majority can and should. Again, propping is critical to allow any anatomical limitations such as shoulder tightness. Use a pillow longitudinally rather than transversely across the abdomen to elevate the shoulders so they can flex to allow the forehead on the hands. If not, keep arms by their side and provide a towel roll under the forehead. This position requires several “stages” of advancement over time and education to engage transversus abdominus, especially for those with spinal stenosis and/or tight hip flexors. The feet should be off the edge of the bed to allow for tightness in plantarflexion.

Working with patients in these three basic positions, while focusing on intercostal breathing, muscle relaxation of the neck, fingers, and other compensatory patterns as we move up the chain, builds a foundation to prepare for functional activities of sit-to-stand, static standing, and movement. These are not stepping stones to be skipped in order to jump into the higher-level functional activities. You would not build a house without a firm foundation. Make sure your patient has the building blocks necessary for the best possible outcomes.

Please join Frank Ciuba and me for our upcoming remote course: Osteoporosis Management: An Introductory Course for Healthcare Professionals on Saturday, Nov 2, 2024. We will discuss osteoporosis-safe exercises, balance and gait activities, and additional ways to help your patients build a strong foundation for movement competence!

Reference:

- Comparison of In Vivo Intradiscal Pressure between Sitting and Standing in Human Lumbar Spine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal ListLife (Basel) PMC8950176 Jia-Qi Li,1 Wai-Hang Kwong,1,* Yuk-Lam Chan,1 and Masato Kawabata2

AUTHOR BIO:

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb Gulbrandson, DPT has been a physical therapist for over 49 years with experience in acute care, home health, pediatrics, geriatrics, sports medicine, and consulting to business and industry. She owned a private practice for 27 years in the Chicago area specializing in orthopedics and Pilates. 5 years ago, Deb and her husband “semi-retired” to Evergreen, Colorado where she works part-time for a hospice and home-care agency, sees private patients as well as Pilates clients in her home studio and teaches Osteoporosis courses for Herman & Wallace. In her spare time, she skis and is busy checking off her Bucket List of visiting every national park in the country- currently 46 out of 63 and counting.

Deb is a graduate of Indiana University and a former NCAA athlete where she competed on the IU Gymnastics team. She has always been interested in movement and function and is grateful to combine her skills as a PT and Pilates instructor. She has been certified through Polestar Pilates since 2005, a Certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist through the Meeks Method since 2008, and a Certified Exercise Expert for the Aging Adult through the Geriatric Section of the APTA.

How does it assist with return to activity?

I recently had a conversation with a sports medicine physician with whom I have shared patients for the past 20 years. He is one of the ‘OG’ physical medicine and rehab physicians in my area, and he has always been a huge advocate for rehab therapies. This physician has spent countless hours in rehab gyms sharing with and learning from physical therapists.

He reached out to me about a mutual patient with a three-year history of pelvic girdle pain that was limiting their activities, including sitting and cycling. This patient was referred to me 6 months ago after plateauing with his sports medicine PT and interventional pain medicine physicians. They had undergone interventions including medications, injections, PT, and group therapy CBT for persistent pain. However, pelvic rehab shifted the needle for this patient, and the physician wanted to learn more about what helped.

Now, this patient has had amazing care already. They were seeing an awesome and skilled sports medicine PT. The patient was engaged and consistent with their self-care program including strengthening, movement, posture, breathing, stretching, bike fit, and activity modification.

What I brought to the table was a focused approach to the pelvic floor region – that was what was missing. We focused our sessions on education about the pelvic floor region including the functional role of the myofascial tissues of the perineum and rectal fossa specifically in the protection of the neurovascular tissues in the perineum, manual therapy, progressive exercise, and return to activities.

When the MD and I reviewed this case, our conversation revolved around manual therapy and how it helps our patients. He wanted to understand how we decide what interventions to utilize to help patients in their recovery. He specifically wanted to understand when to touch and when to focus on strength/movement only. My answer was simpler than that. I felt that most of our patients needed both throughout their course of care.

We discussed that one of the main things for this patient was that they did not realize that myofascial tissues attached in the perineum could impact their sitting. More specifically, they did not realize that there were muscles located in the pelvic region that they could engage, relax, lengthen, and strengthen. Upon assessment, this patient had decreased pliability of the tissues in the urogenital triangle and rectal fossa which contributed to less tolerance to sitting, likely due to compression of neurovascular structures in the perineum. With manual therapy, we were able to increase the pliability of those tissues and increase the patient’s awareness of the myofascial tissues. We also spent time in our sessions having the patient learn to engage, release, and lengthen the PF muscles.

With manual therapy, the patient became aware of those muscles and with tactile cues learned how to actively engage with those muscles. After about 4 weeks, the patient began gradually returning to sitting and to time on the bike. We continued manual therapy while the patient built tolerance and confidence to sitting on a chair and a bike saddle.

I utilized manual therapy to assist the patient with gaining awareness of the pelvic floor region, and we continued these manual therapy sessions to assist with recovery from increasing sitting. Ultimately, the patient could return to cycling and sitting without limits. The patient also learned how to self-manage with their already established self-care and we added focused pelvic floor region stretching, recovery, and awareness.

The Physician and I discussed the commentary by Short et al 2023 about manual therapy in return to sport and recovery. The commentary has a great statement supporting manual therapy usage: “The benefits of manual therapy, which includes building therapeutic alliance via touch, improving function via safe, cost-effective short-term pain modulation and facilitating education and exercise to be more impactful when they are limited less by pain and anxiety” for return to activity. In pelvic health rehab practice by using manual therapy, we can help the patient become aware of a part of their body, decrease apprehension to touch and pressure to the area, and then focus on the patient's self-care to promote long-term recovery and self-reliance.

This fostered further discussion with the MD about mechanical touch and how it affects the body. Short et al 2023 further stated “When a therapist provides a manual intervention, a mechanical stimulus is applied upon an athlete and produces input into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord…….initiating a multi-factorial cascade of neurophysiologic effects stemming from the nervous system. Both the peripheral and central nervous system provide signal pathways that induce responses throughout the body. These include neuromuscular (i.e., muscle activity), autonomic (i.e., heart rate, cortisol), endocrine (opioid) pain modulatory, and non-specific (context, beliefs fear, expectations, etc.) responses.” Put in these terms the physician had a better understanding of the multifactorial level that physical touch can assist with patient recovery.

Utilizing manual therapy techniques/therapeutic touch is foundational to helping patients become aware of their patterns of movement or stiffness and parts of their body. In Manual Therapy for the Abdominal Wall, scheduled on October 20th, 2024, we discuss these concepts and apply manual therapy techniques to the abdominal wall. While for this class we utilize the abdominal wall to practice, the skills learned can then be applied throughout the body. This is a foundational class for anyone who wants to build their skills in manual therapy and then take those skills to further advance their patient care in any part of the body. We do discuss specific abdominal wall conditions such as abdominal wall post-surgical incisions and hernia, but we apply the basic manual therapy techniques to them that could then be applied anywhere in the body including the perineum and rectal fossa.

Reference:

Short S, Tuttle M, Youngman D. A Clinically Reasoned Approach to Manual Therapy in Sports Physical Therapy. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2023 Feb 1;18(1):262-271. doi: 10.26603/001c.67936. PMID: 36793565; PMCID: PMC9897024.

AUTHOR BIO:

Tina Allen, PT, PRPC, BCB-PMD

Tina Allen, PT, PRPC, BCB-PMD (she/her) has been a physical therapist since 1993. She received her PT degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her initial five years in practice focused on acute care, trauma, and outpatient orthopedic physical therapy at Loyola Medical Center in Illinois. Tina moved to Seattle in 1997 and focused her practice in Pelvic Health. Since then she has focused her treatment on the care of all genders throughout their life spans with bladder/bowel dysfunction, pelvic pain syndromes, pregnancy/ postpartum, lymphedema, and cancer recovery.

Tina Allen, PT, PRPC, BCB-PMD (she/her) has been a physical therapist since 1993. She received her PT degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her initial five years in practice focused on acute care, trauma, and outpatient orthopedic physical therapy at Loyola Medical Center in Illinois. Tina moved to Seattle in 1997 and focused her practice in Pelvic Health. Since then she has focused her treatment on the care of all genders throughout their life spans with bladder/bowel dysfunction, pelvic pain syndromes, pregnancy/ postpartum, lymphedema, and cancer recovery.

Tina’s practice is at the University of Washington Medical Center in the Urology/Urogynecology Clinic where she treats alongside physicians and educates medical residents on how pelvic rehab interventions will assist clients. She presents at medical and patient conferences on topics such as pelvic pain, continence, and lymphedema. Tina has been faculty at Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute since 2006. She was the physical therapist provider for the University of Washington on a LURN Multi-Center study for Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome treatment with physical therapy techniques. Tina was also a co-investigator for a content package on pain education for the NIDA/NIH on the treatment of pelvic pain.

Each profession has its own code of ethics to give guidelines for the professional to act. This is the case for lawyers, doctors, mental health therapists, massage therapists, and accountants to name a few. In pelvic rehabilitation, the APTA and AOTA make different guidelines for physical therapists and occupational therapists respectively.

For physical therapists, the Code of Ethics is built upon the physical therapist's five roles, the profession's core values, and the multiple realms of ethical action. For occupational therapists, the code serves the two purposes of providing aspiration core values in professional and volunteer roles as well as delineating ethical principles and enforceable standards of conduct.

There are many areas of overlap and differences between the roles of physical and occupational therapists in pelvic rehabilitation. This blog will explore the areas that overlap in the world of ethical decision-making. Pelvic floor therapists must complete tasks such as management of patients/clients, consultation, education, research, and administration. Ethical realms can be individual, organizational, and societal and there are various situations an individual can find themselves in when providing care including problems, issues, dilemmas, temptation, distress, and silence.

Some of the main tenets of medical care include beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice. Beneficence is acting in the patient's best interest. Nonmaleficence means "Do no harm" with the care and interactions provided. Autonomy is giving patients the freedom to choose, when and where they are able. Justice is ensuring fairness in patient care.

The AOTA code of ethics tells us that occupational therapists are “committed to promoting inclusion, participation, safety, and well-being for all recipients of service in various stages of life, health, and illness and to empowering all beneficiaries of service to meet their occupational needs.” Likewise the APTA states there is an “obligation of physical therapists to empower, educate, and enable those with impairments, activity limitations, participation restrictions, and disabilities to facilitate greater independence, health, wellness, and enhanced quality of life.”

What can a therapist do to make sure they are practicing ethically? First, they can do a core values assessment. These will vary based on the person’s profession. For example, some core values of a physical therapist include accountability, altruism, collaboration, compassion and caring, duty, excellence, integrity, and social responsibility. Parallelly, occupational therapists have altruism, equality, freedom, justice, dignity, truth, and prudence. You can see there is overlap and similarities between these professions and the expectation of the care they should provide.

One of the pre-course activities I ask participants to perform before doing one of my ethics classes is a core values assessment. This is a great way to check in with where you think you are in your practice and where you may want or need to make changes. After having taught about ethics since 2022, I have found many people are struggling because they want very much to follow rules and be ethical and they simply don’t know where to find the right answers. They turn to Facebook support groups or advice from colleagues and while this information is valuable, it may not always give them accurate information.

The Code of Ethics for PTs and OTs gives clear outlines of the standards of care that these professionals should be providing, but sometimes people need help with the interpretation. It seems so straightforward as you read the document and agree with the words on the paper, but then your patient, employer, or profession throws a curveball at you.

Here are some examples of everyday scenarios pelvic health providers run into that require ethical guideline knowledge and decision-making.

- You have a cancellation policy and the patient canceled in a way that incurred a charge. They give you permission to bill their insurance for the visit so you get paid and they don’t have to pay the fee.

- A patient comes in with their partner and the partner dictates the entire evaluation, refusing to let the patient speak to you alone, and pressuring you to perform tests and measures the patient doesn’t feel comfortable with.

- Your patient needs vaginal dilators and doesn’t feel comfortable asking their provider for a prescription. You struggle with how to advise them.

- You’re a therapist working in the school district and find out a teacher has punished a student on your caseload by putting them in a closet.

- You’re hiring a new provider and they didn’t pass their boards the first time. They ask if they can start treating under your supervision while they study for the next round of boards.

- Pessaries require a prescription in your state but you know your patient would benefit from one and you have a free, unused sample in your office you want to try with them.

- Your patient reports they cannot afford lubricant and you know it would benefit them. You have given them multiple samples. They ask if they can have your large clinical tube.

It is our job as pelvic health providers to know these guidelines, know what our core values are, know the expectations of us as practitioners, and utilize all of this information in a way that benefits all aspects of our patients within our practice. We must continue to aim to do no harm, be truthful, be kind, considerate, inclusive, and aware of all that our clients are going through in order to help them reach their goals. If you feel like these situations happen to you a lot, then you’re likely sensitive to the rules and regulations, and so when a problem arises, your mind flags it and tries to solve it.

If you’re looking for help and guidance in the area of ethics, particularly a crash course in the background of ethics, followed by in-depth application to specific topics, Herman & Wallace has three options of classes to fulfill your continuing education requirements and help ease any burden you may be feeling by the weight of some of these heavier scenarios.

- Ethical Concerns for Pelvic Health Professionals - January 12, 2025

- The purpose of this class is to explore the ethical challenges Pelvic Health Practitioners may experience including consent, managing trauma and abuse, and preventing misconduct. This course is for any Pelvic Health Professional looking to build skills for ethical evaluation, problem-solving, and derivation of solutions.

- Ethical Considerations from a Legal Lens - November 17, 2024

- The purpose of this class is to explore the ethical challenges Pelvic Health Practitioners may experience from a health law perspective. This course is for any Pelvic Health Professional looking to build skills for ethical evaluation, problem-solving, and derivation of solutions with a specific focus on the legalities and related concepts.

- Ethical Considerations for Pediatric Pelvic Health - October 13, 2024

- The purpose of this class is to explore the ethical challenges pediatric pelvic health practitioners may experience including consent, managing situations of trauma and abuse, and managing autonomy for minors. This course is for any pelvic health professional looking to build skills for ethical evaluation, problem-solving, and derivation of solutions when working with pediatric clients.

AUTHOR BIO:

Mora Pluchino, PT, DPT, PRPC

Mora Pluchino, PT, DPT, PRPC (she/her) is a graduate of Stockton University with a BS in Biology (2007) and a Doctorate of Physical Therapy (2009). She has experience in a variety of areas and settings, working with children and adults, including orthopedics, bracing, neuromuscular issues, vestibular issues, and robotics training. She began treating Pelvic Health patients in 2016 and now has experience treating women, men, and children with a variety of Pelvic Health dysfunction. There is not much she has not treated since beginning this journey and she is always happy to further her education to better help her patients meet their goals.

She strives to help all of her patients return to a quality of life and activity that they are happy with for the best bladder, bowel, and sexual functioning they are capable of at the present time. In 2020, She opened her own practice called Practically Perfect Physical Therapy Consulting to help meet the needs of more clients. She has been a guest lecturer for Rutgers University Blackwood Campus and Stockton University for their Pediatric and Pelvic Floor modules since 2016. She has also been a TA with Herman & Wallace since 2020 and has over 150 hours of lab instruction experience. Mora has also authored and instructs several courses for the Institute.

![]()

Central nervous system damage or disease can have a significant negative impact on pelvic organ and pelvic muscle function, adding to the functional burden that we may observe with movement, ADL, and communication/cognition deficits. The intricacies of central nervous system involvement in pelvic organ function can be traced back to our early years of development. Learning to walk and talk as a child happens before the ability to control our bladder and bowel emptying. This level of control requires a well-developed, intricately organized central and autonomic nervous system. It is understandable then, that even minor damage to our central nervous system and nerve pathways can compromise the intricacies of the complexly integrated pelvic viscera and pelvic floor dynamic.

Neurogenic bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction are generally defined as an impairment in these organs that results from neurologic damage or disease. The prevalence of neurogenic bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction is somewhat uncertain due to limited studies in the neurologic population, however, typically the reports present a wide range. Neurogenic pelvic impairments can be highly variable and dependent on several factors including, but not limited to, lesion level, traumatic etiology (i.e., head, or spinal cord injury), non-traumatic etiology (i.e., stroke, Parkinson’s, Multiple Sclerosis), and comorbidities. The complexity of the person with a central nervous system pathology, whether it be damage or disease, can challenge even the most experienced clinician, and evaluating and treating these individuals can seem like a daunting and intimidating endeavor. Additionally, therapeutic intervention studies in the neurologic population are also less abundant, and individuals with neurologic deficits are often excluded.

Understanding your patient’s neurologic diagnosis, level of injury and corresponding probable neurological system impairments can help you decide on the best assessment and intervention strategy for your patient. Let’s first consider an upper motor neuron (UMN) lesion. This type of lesion can occur in the cortex and even down through the spinal cord descending motor tracts, which are located in the columns of the spinal cord. These individuals typically experience predominant bladder storage dysfunction or detrusor overactivity, increased muscle tone/spasticity in the pelvic floor, and reflexive bowel function. In contrast, a lower motor neuron (LMN) lesion can occur anywhere along the spinal cord within the LMN cell bodies in the anterior horns, along the pathway of a peripheral motor nerve, or at the motor neuromuscular junction. These individuals typically experience bladder storage or voiding symptoms, possible elevated post-void residuals if injury affects the sacral reflex arc, pelvic floor laxity or weakness, impaired descending and rectosigmoid transit, and areflexive bowel function.

In my course Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation scheduled for November 1-2, we will review basic neuroanatomy concepts. We will take a deep dive into the autonomic nervous system's control of the bladder, bowel, and sexual health organs. This will provide a general overview for considering the level of neurologic injury and the impairments you will likely observe. Parkinson disease will be our primary focus, however, my hope is that you can also begin to generalize this knowledge to other neurologic conditions that you treat in your clinic.

Resources:

- Fowler, C. J., Panicker, J. N., & Emmanuel, A. (Eds.). (2010). Pelvic organ dysfunction in neurological disease: clinical management and rehabilitation. Cambridge University Press.

- Lamberti, G., Giraudo, D., & Musco, S. (Eds.). (2019). Suprapontine Lesions and Neurogenic Pelvic Dysfunctions: Assessment, Treatment and Rehabilitation. Springer Nature.

AUTHOR BIO:

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC (she/her) graduated with her master’s degree in Occupational Therapy from Concordia University Wisconsin in 2002 and works for Aurora Health Care at Aurora Sinai Medical Center in downtown Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Erica specializes in female, male, and pediatric evaluation and treatment of the pelvic floor and related bladder, bowel, and sexual health issues. She is board-certified in Biofeedback for Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction (BCB-PMD) and is a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner (PRPC) through Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC (she/her) graduated with her master’s degree in Occupational Therapy from Concordia University Wisconsin in 2002 and works for Aurora Health Care at Aurora Sinai Medical Center in downtown Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Erica specializes in female, male, and pediatric evaluation and treatment of the pelvic floor and related bladder, bowel, and sexual health issues. She is board-certified in Biofeedback for Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction (BCB-PMD) and is a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner (PRPC) through Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

Erica has attended extensive post-graduate rehabilitation education in the area of Parkinson disease and exercise. She is certified in LSVT (Lee Silverman) BIG and is a trained PWR! (Parkinson’s Wellness Recovery) provider, both focusing on intensive, amplitude, and neuroplasticity-based exercise programs for people with Parkinson disease. Erica is an LSVT Global faculty member. She instructs both the LSVT BIG training and certification course throughout the nation and online webinars. Erica partners with the Wisconsin Parkinson Association (WPA) as a support group, event presenter, and author in their publication, The Network. Erica has taken a special interest in the unique pelvic floor, bladder, bowel, and sexual health issues experienced by individuals diagnosed with Parkinson disease.

Tara Sullivan instructs her course Sexual Medicine in Pelvic Rehab on October 19-20. Her course provides a thorough introduction to pelvic floor sexual function, dysfunction, and treatment interventions of all sexual orientations, as well as an evidence-based perspective on the value of physical therapy interventions for patients with chronic pelvic pain related to sexual conditions, disorders, and multiple approaches for the treatment of sexual dysfunction including understanding medical diagnosis and management.

Menopause is a natural phase in a woman's life, signaling the end of her reproductive years. While many are familiar with common symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, brain fog, and mood changes, there is another less-discussed condition that affects many women: Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM). GSM encompasses a range of symptoms affecting the genital and urinary systems, profoundly impacting a woman’s quality of life. Understanding GSM is crucial for women entering menopause and healthcare providers, especially pelvic floor specialists.

What is Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM)?

Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM) refers to a collection of signs and symptoms associated with the changes in estrogen levels that occur during menopause. These hormonal changes affect the tissues of the vulva, vagina, urethra, and bladder, leading to a variety of symptoms that can be both uncomfortable and disruptive.

GSM was formerly referred to as vulvovaginal atrophy, but this term was considered limited because it didn’t encompass the full scope of symptoms women experience, particularly those related to the urinary system. The term "GSM" is now preferred as it better reflects the diverse nature of the condition.

Common Symptoms of GSM

- Vaginal Dryness and Irritation: One of the most frequently reported symptoms of GSM is vaginal dryness. This occurs because estrogen levels drop, causing the vaginal tissue to become thinner, less elastic, and less lubricated. This dryness can lead to itching, burning, and irritation.

- Painful Intercourse (Dyspareunia): Vaginal dryness can make sexual activity uncomfortable or even painful. Women may also experience tearing or bleeding during intercourse due to the thinning of the tissue specifically around the vaginal opening.

- Urinary Symptoms: GSM can cause a range of urinary issues, including increased frequency of urination, urgency, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and incontinence. Estrogen plays a role in maintaining the health of the urinary tract, so its decline can lead to irritation and increased susceptibility to infections.

- Pelvic Floor Dysfunction: abnormal tone or weakening of pelvic floor muscles exacerbates urinary symptoms and pain, and contributes to conditions like pelvic organ prolapse.

- Changes in Vaginal pH: Estrogen plays a critical role in maintaining a healthy vaginal environment. With lower estrogen levels, the vaginal pH becomes less acidic, making the area more susceptible to infections such as bacterial vaginosis and yeast infections.

Causes and Risk Factors

GSM is directly related to the reduction in estrogen production during menopause. Estrogen is responsible for maintaining the thickness, elasticity, and moisture of the vaginal and urinary tissues. As levels drop, these tissues undergo changes that lead to GSM.

While GSM is most commonly associated with natural menopause, it can also occur in women who experience early menopause due to surgery or cancer treatments like chemotherapy and radiation. Women who smoke or have never given birth vaginally are also at a higher risk for developing GSM.

Treatment Options:

The good news is that GSM is treatable. While you might think, systemic hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is enough to resolve GSM, that’s not typically the case. More often, even if one is on already on estrogen HRT, or for those who cannot or will not take systemic estrogen, they can still apply a low dose estradiol cream specifically to the vestibule, urethra, and vaginal opening to target the tissue most affected by GSM. Local topical estradiol cream is considered a safe option. In a recent article, “In a large, claims-based analysis, we did not find an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence within 5 years in women with a personal history of breast cancer who were using vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause”

However, if one is still opposed to using estradiol, other non-hormonal options are available to treat GSM symptoms:

- Vaginal Moisturizers and Lubricants: For women experiencing mild symptoms, over-the-counter vaginal moisturizers and lubricants can provide relief from dryness and discomfort. These products can be used regularly to help maintain vaginal moisture and make intercourse more comfortable.

- Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy: Many women with GSM benefit from pelvic floor physical therapy, which can strengthen the muscles of the pelvic floor, improve bladder control, and enhance sexual function. Physical therapists specialized in pelvic health can provide individualized treatments to address specific concerns.

- Laser Therapy: A newer, non-invasive option for GSM is laser therapy, such as fractional CO2 lasers. This therapy stimulates collagen production in the vaginal tissues, promoting healing and improving symptoms of dryness, pain, and laxity.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Quitting smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, and staying sexually active can also help reduce symptoms of GSM. Regular sexual activity increases blood flow to the vaginal area, helping to maintain tissue health.

Our Role as Pelvic Floor Therapist:

Despite affecting up to half of postmenopausal women, GSM remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. Many women may feel uncomfortable discussing these symptoms with their healthcare providers, or they may assume that these changes are a natural part of aging that must be endured. That is where pelvic floor specialists have a unique opportunity to educate these women. We have the luxury of one-on-one time and we are one of the only specialists that fully assess the vulvar tissue, specifically the vestibule and urethral opening where GSM is most identifiable. Understanding the research on estradiol treatment as well as other non-hormonal options can greatly improve our patients' quality of life.

Join Tara Sullivan in her upcoming course to learn more about Sexual Medicine in Pelvic Rehab on October 19-20. Lecture topics include hymen myths, squirting, G-spot, prostate gland, sexual response cycles, hormone influence on sexual function, anatomy and physiology of pelvic floor muscles in sexual arousal, orgasm, and function and specific dysfunction treated by physical therapy in detail including vaginismus, dyspareunia, erectile dysfunction, hard flaccid, prostatitis, post-prostatectomy; as well as recognizing medical conditions such as persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD), hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and dermatological conditions such as lichen sclerosis and lichen planus.

Resource:

- Agrawal P, Singh SM, Able C, Dumas K, Kohn J, Kohn TP, Clifton M. Safety of Vaginal Estrogen Therapy for Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause in Women With a History of Breast Cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Sep 1;142(3):660-668. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005294. Epub 2023 Aug 3. PMID: 37535961. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37535961/

AUTHOR BIO:

Tara Sullivan, PT, DPT, PRPC, WCS, IF

Dr. Tara Sullivan, PT, PRPC, WCS, IF (she/her) started in the healthcare field as a massage therapist practicing for over ten years, including three years of teaching massage, anatomy, and physiology. During that time, she attended college at Oregon State University earning her Bachelor of Science degree in Exercise and Sport Science, and she continued to earn her Masters of Science in Human Movement and Doctorate in Physical Therapy from A.T. Still University. Dr. Tara has specialized in Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (PFD) treating bowel, bladder, sexual dysfunctions, and pelvic pain exclusively since 2012. She has earned her Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification (PRPC) deeming her an expert in pelvic rehabilitation, treating men, women, and children. Dr. Sullivan is also a board-certified clinical specialist in women’s health (WCS) through the APTA and a Fellow of the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (IF).

Dr. Tara Sullivan, PT, PRPC, WCS, IF (she/her) started in the healthcare field as a massage therapist practicing for over ten years, including three years of teaching massage, anatomy, and physiology. During that time, she attended college at Oregon State University earning her Bachelor of Science degree in Exercise and Sport Science, and she continued to earn her Masters of Science in Human Movement and Doctorate in Physical Therapy from A.T. Still University. Dr. Tara has specialized in Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (PFD) treating bowel, bladder, sexual dysfunctions, and pelvic pain exclusively since 2012. She has earned her Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification (PRPC) deeming her an expert in pelvic rehabilitation, treating men, women, and children. Dr. Sullivan is also a board-certified clinical specialist in women’s health (WCS) through the APTA and a Fellow of the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (IF).

Dr. Tara established the pelvic health program at HonorHealth in Scottsdale and expanded the practice to 12 locations across the valley. She continues treating patients with her hands-on individualized approach, taking the time to listen and educate them, empowering them to return to a healthy and improved quality of life. Dr. Tara has developed and taught several pelvic health courses and lectures at local universities in Arizona including Northern Arizona University, Franklin Pierce University, and Midwestern University. In 2019, she joined the faculty team at Herman and Wallace teaching continuing education courses for rehab therapists and other health care providers interested in the pelvic health specialty, including a course she authored-Sexual Medicine in Pelvic Rehab, and co-author of Pain Science for the Chronic Pelvic Pain Population. Dr. Tara is very passionate about creating awareness of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and launched her website pelvicfloorspecialist.com to continue educating the public and other healthcare professionals.

In March 2024, Dr. Tara left HonorHealth and founded her company Mind to Body Healing (M2B) to continue spreading awareness on pelvic health, mentor other healthcare providers, and incorporate sexual counseling into her pelvic floor physical therapy practice. She has partnered with Co-Owner, Dr. Kylee Austin, PT.

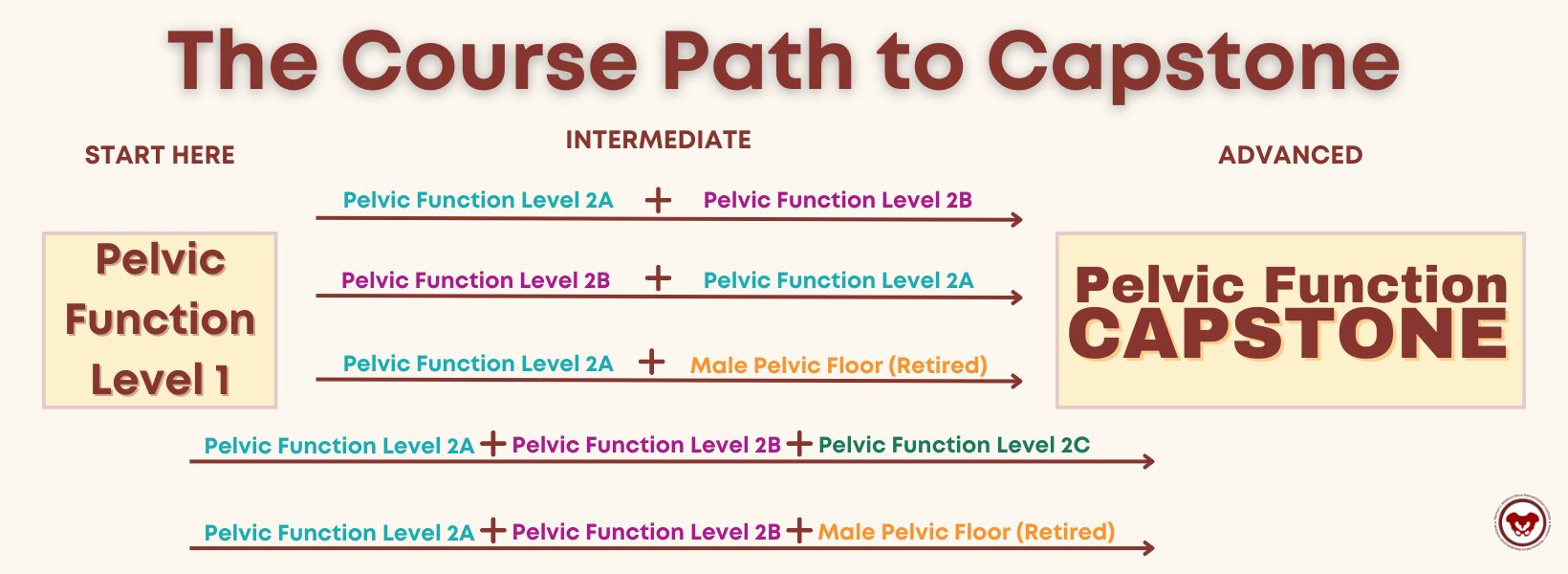

![]()

Most practitioners know that Capstone is the advanced level course that caps off the Pelvic Function Series. This article covers two main questions:

- Why should you aspire to Capstone?

- What is the course path to Capstone?

- Where do you go after Capstone?

Why should you aspire to Capstone?

If you are new to pelvic rehabilitation or an experienced practitioner, you should think about taking Pelvic Function Capstone. For beginner practitioners who are interested in completing the Pelvic Function Series, the Capstone path will take you from the introductory Pelvic Function Level 1, where you learn intra-vaginal exam techniques, through Pelvic Function Level 2A, which includes an introduction to anorectal examination. AND you can tailor your course journey to your patient demographics.

For our advanced practitioners, Capstone is an excellent way to round out your course journey and really focus on those more advanced topics that you see in pelvic rehabilitation such as endometriosis, infertility, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), surgery complications, gynecological cancers, neuroanatomy, and the role of pharmacology and nutrition in pelvic health/pelvic pain.

What is the course path to Capstone?

'

'The Pelvic Function Series includes six courses, but you do not need to take all the courses in order to register for Pelvic Function Capstone. The Pelvic Function Courses include:

- Pelvic Function Level 1: Introduction to Pelvic Health. Intra-vaginal exam will be introduced in labs.

- Pelvic Function Modalities: The Pelvic Health Toolkit. This is an in-person lab course featuring a variety of modalities.

- Pelvic Function Level 2A: Colorectal Pelvic Health and Pudendal Neuralgia, Coccyx Pain. Anorectal internal exam will be introduced in labs.

- Pelvic Function Level 2B: Urogynecologic Topics in Pelvic Health.

- Pelvic Function Level 2C: the Male Pelvic Floor and Men’s Pelvic Health.

- Pelvic Function Series Capstone: Integration of Advanced Concepts in Pelvic Health.

While you do need to take Pelvic Function Level 1 first - you should choose your next course based on your patient demographics. A lot of practitioners see patients with fecal incontinence or coccyx pain, and so after PF1, they may choose to prioritize PF2A as the next step in their journey. Others may see patients with penile pain or incontinence post-prostatectomy and may choose to take 2C as their next step.

The course path options:

- · If you have taken PF1 and 2B, you must take 2A prior to Capstone.

- · If I have taken PF1, 2A, and 2B - you may advance to Capstone.

- · If you have taken PF1, 2A, and the Male Pelvic Floor course, you may advance to Capstone

- · If you have taken PF1, 2A, 2B, and the Male Pelvic Floor course, you may advance to Capstone

Where do you go after Capstone?

If you are in the elite few that have taken Capstone, then congratulations! You may be asking yourself “Where do I go now?” There are a few options depending on your interests.

Here are some recommended courses:

- · Ramona Horton’s Visceral Mobilization Series – if you are looking for a fascial course for hands-on skills

- · Nerves and the Nervous System Courses – Pudendal Neuralgia, Sacral Nerve, and Lumbar Nerve

- · Oncology of the Pelvic Floor Series

- · Parkinson Disease

- · Pain Science for the Chronic Pelvic Pain Population

- · Pharmacologic Considerations for the Pelvic Health Provider

- · Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist

If you are thinking of further certification then it may be time to look into the Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification process. While there is no required coursework one must complete to sit for the PRPC exam, having several courses from beginner to advanced levels under your belt is certainly helpful.

Ready, Set, Go!

There’s nothing left to do but do it! Sign up for a Capstone course with HW.

The weekend of October 19-20 is the next scheduled Capstone Course that has several satellites and a self-hosted option for attendance:

- Bethpage NY

- Boston MA

- Houston TX

- New York NY

- Raleigh NC

- Salt Lake City UT

- Sellersville PA

- Self-Hosted

We look forward to seeing you in a course soon!

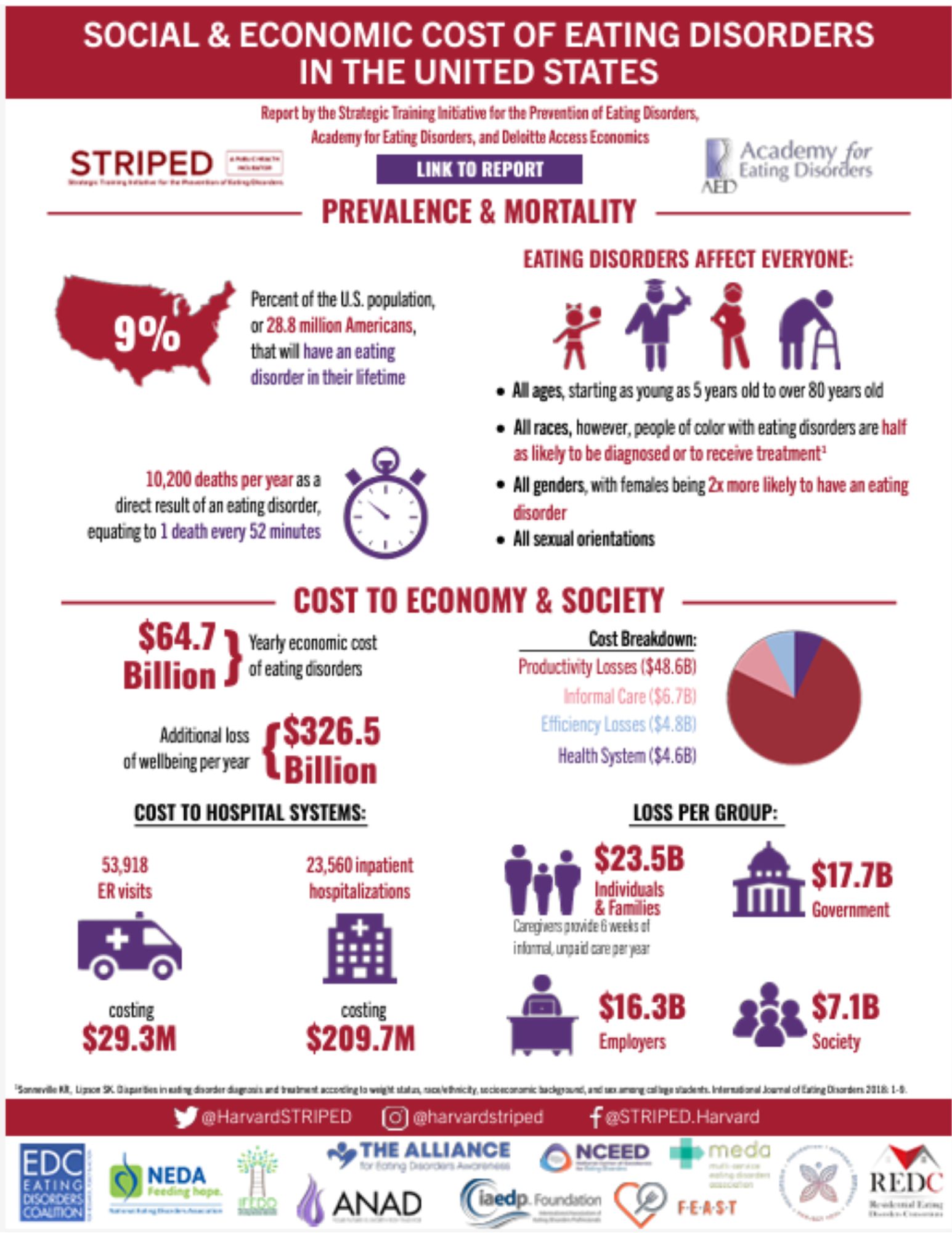

HW faculty member Carole High Gross, PT, MS, DPT, PRPC instructs her remote course, Eating Disorders and Pelvic Health Rehabilitation, on October 19-20, 2024 that takes a deep dive into the role of pelvic health rehabilitation with individuals with eating disorders.

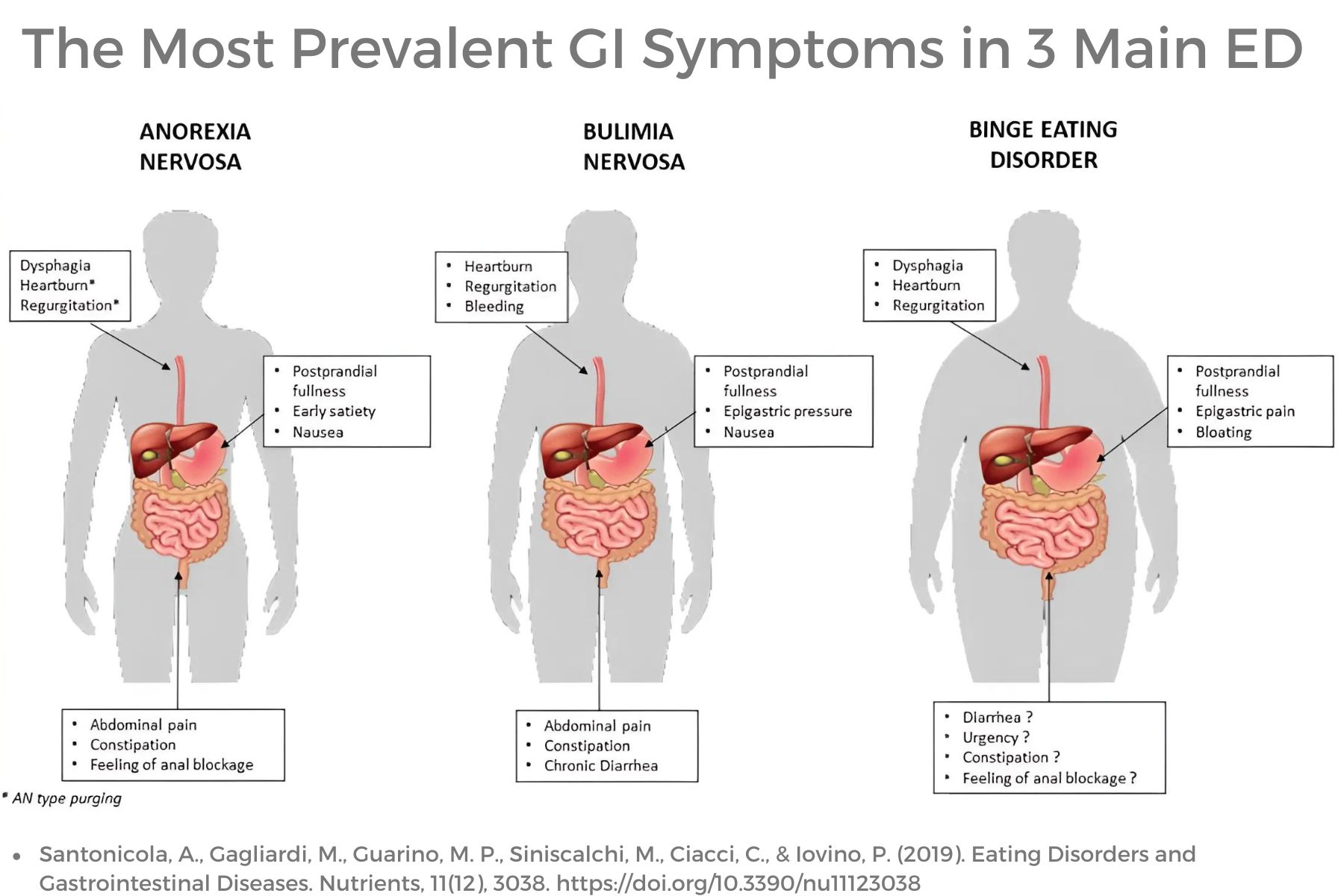

The role of a pelvic health rehabilitation professional includes caring for individuals with dysfunction within the pelvis and abdominal canister. We treat individuals with constipation, fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, urinary dysfunction, pelvic pain, abdominal pain, and bloating (to name a few). Individuals with eating disorders often experience ALL of these symptoms. Numerous studies demonstrate bowel, bladder, and pelvic dysfunction in those with eating disorders (see reference list for some of these studies). We CAN help!

Eating disorders are mental health conditions with serious biopsychosocial implications that negatively impact the function of the body, social interactions, and psychological well-being. The American Psychiatric Association characterizes Eating Disorders (ED) as “behavioral conditions characterized by severe and persistent disturbance in eating behaviors and associated distressing thoughts and emotions.” Types of eating disorders include:

- anorexia nervosa (AN)

- bulimia nervosa (BN)

- binge eating disorder (BED)

- avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

- other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED)

- pica and rumination disorder

Eating disorders are estimated to affect roughly 5% of the population and are often under-reported and unidentified by the medical community. People of all genders often suffer in silence as eating disorders tend to be a very secretive and all-consuming mental illness that does not discriminate based on gender, culture, race, or nationality. Eating disorders can develop at any time in someone’s life, however, often signs develop in adolescence and early adulthood.

Supporting Research

One noteworthy article, which was published in May of 2024, was written by Monica Williams and colleagues from ACUTE, an inpatient eating disorder treatment facility, in Denver, Colorado. Williams et al. published a retrospective cohort study of 193 female women highlighting pelvic floor dysfunction in people with eating disorders. This study illustrated the positive effects of management (including education, pelvic floor muscle assessment, biofeedback, and active retraining of the pelvic muscle) on pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) with the intervention group (n=84). Each of the patients in this study had only one to a few treatment sessions of selected appropriate interventions.

Williams et al. published a retrospective cohort study of 193 female women highlighting pelvic floor dysfunction in people with eating disorders. This study illustrated the positive effects of management (including education, pelvic floor muscle assessment, biofeedback, and active retraining of the pelvic muscle) on pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) with the intervention group (n=84). Each of the patients in this study had only one to a few treatment sessions of selected appropriate interventions.

The control group received the standard of care education including mindfulness, relaxation techniques, and diaphragmatic breathing. All participants in the intervention group received a 30-minute education session which included the purpose of the pelvic floor, causes of pelvic floor dysfunction, the relationship between the pelvic floor and diaphragm, typical bladder norms, strategies to improve bowel/bladder emptying and urge suppression techniques. The Education Group (n=26) received education only without other interventions. Although this group showed improvements in the PFDI score, the improvements did not meet statistically meaningful improvement in pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms. However, the other treatment subgroups within the intervention group showed statistically meaningful improvements in pelvic floor dysfunction. The Pelvic Floor Assessment group (n=13) included individuals who received the education (noted above) and internal assessment of pelvic floor musculature with the goal of improving coordination of PFM.

The Urinary Distress Inventory 6 (UDI-6) demonstrated statistically significant improvement in the Pelvic Floor Assessment Group. The UDI-6, the Colorectal-Anal Inventory 6 (CRAD-8), and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory 6 (POPDI-6) improved with the Active Retraining (of the pelvic floor muscles) Group (n=67). The individuals in the Active Retraining group received: Education (mentioned above) and bladder training (improving time between voids) and pelvic floor stretches (deep squat, butterfly, child’s pose, happy baby including coordination of diaphragmatic breathing and movement of the pelvic floor). The Biofeedback Group (n=3) received Education (mentioned above) and biofeedback including visual feedback to instruct patients on how to effectively contract and relax PFM. The Biofeedback Group showed statistical improvement with the POPDI-6 score.

Overall, Williams et al. concluded that patients with eating disorders report an increased level of pelvic floor symptoms. The interventions provided in this study were found to be beneficial. Individuals with the anorexia binge-purge subtype also had higher scores on the PFDI than the anorexia nervosa restricting subtype. The authors recommended future studies to better describe the etiology of PFD in individuals with ED and how PFD contributes to both behaviors and GI symptoms of those with eating disorders.

Ng et al., 2022, discussed research that demonstrated the relationship between eating disorders and urinary incontinence through the lens of psychoanalysis. This article described mental health co-morbidities with eating disorders that contribute to urinary dysfunction. The authors also encouraged a good psychodynamic understanding of childhood relationships, personality traits, and the inner mental “landscape.” The authors reinforced mental co-morbidities contribute to increased urinary incontinence and dysfunction including poor interoceptive awareness, personality traits, decreased life satisfaction, need for control, and anxiety.

This article described mental health co-morbidities with eating disorders that contribute to urinary dysfunction. The authors also encouraged a good psychodynamic understanding of childhood relationships, personality traits, and the inner mental “landscape.” The authors reinforced mental co-morbidities contribute to increased urinary incontinence and dysfunction including poor interoceptive awareness, personality traits, decreased life satisfaction, need for control, and anxiety.

Ng and colleagues described the prominence of poor interoceptive awareness among individuals with eating disorders. Interoceptive awareness refers to awareness of one’s feelings or emotions. This may also affect a person’s perception of stimuli arising in the body, such as to perform bodily functions such as urination. Poor interoceptive awareness would likely also play a factor in awareness of the body’s need to evacuate stool however, this was not within the scope of this article. Bowel dysfunction with ED is well documented in the research.

Ng et al’s article also discusses common personality traits among individuals with some eating disorders including perfectionism and asceticism. Asceticism refers to the self-denial of physical or psychological desires or needs and can also be viewed as a ritualization of life. Often this refers to spirituality or religious practices, however, denial of bodily urges and the need for control is a common characteristic with some eating disorders which include restriction (AN, BN, OSFED). Denial of basic needs, such as urination, would reasonably reinforce the need for control. Often those with restrictive eating disorders excessively control what goes into the body and may also be restricting what is coming out of the body including feces and urine.

Anxiety and other mental health comorbidities are common in individuals with ED and can contribute to increased tone and tension in the pelvic floor contributing to urinary dysfunction. Additional research supports that this increased pelvic tone and tension also contributes to sexual dysfunction, pelvic pain, and bowel dysfunction in individuals with and without eating disorders. Mental health challenges may also lead to closed posturing, tightness in the back, hip, and shoulder musculature as well as upper chest breathing, and poor excursion of the diaphragm.

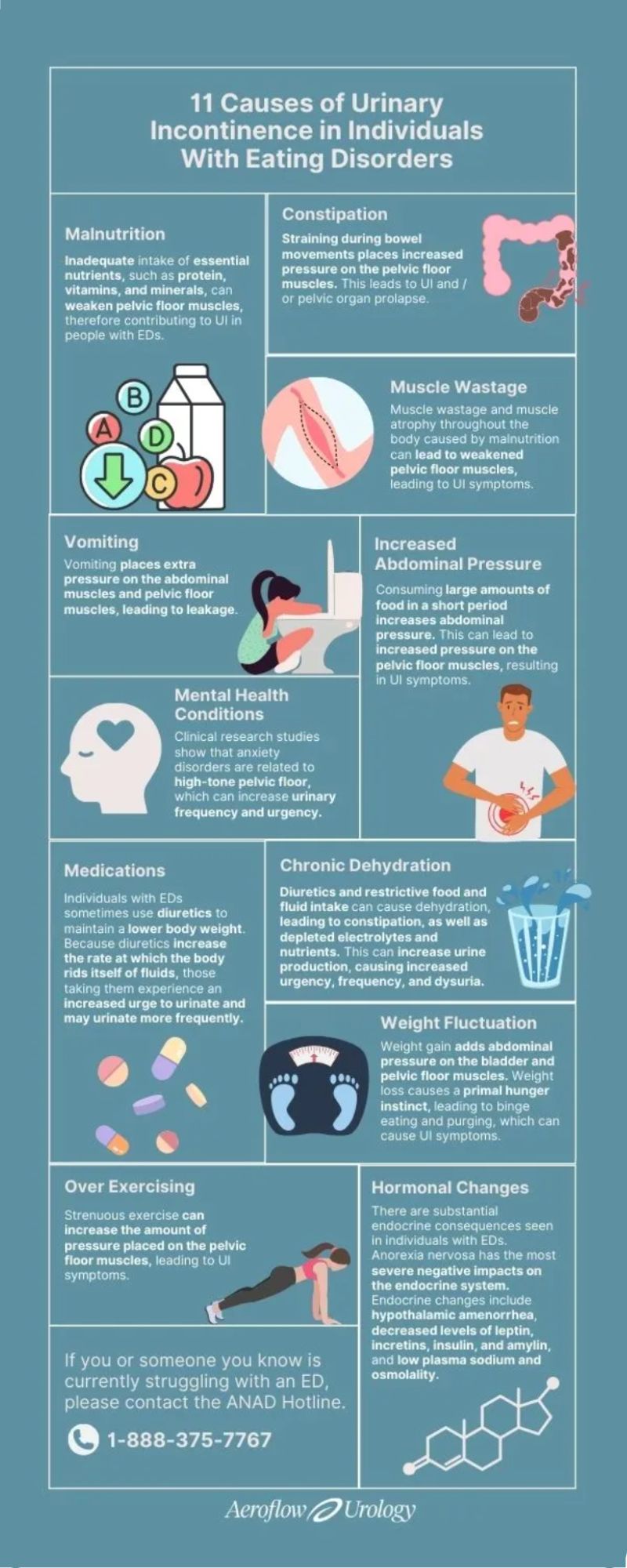

As pelvic health rehabilitation providers, we need to look at the whole person as so many factors influence pelvic-related dysfunction. Numerous factors affect bowel, bladder, and pelvic function including muscle wasting and atrophy, slow GI motility, medications, hormonal changes, weight fluctuations, purging behaviors, poor pressure management, increased intra-abdominal pressure, mental wellness comorbidities, excessive exercise, water loading, dehydration, malnutrition, poor postural alignment, length and tension of muscular and fascial systems, diaphragmatic/lower costal excursion and diversity of microbiome to name a few.

Septak posted a blog in February 2024 for the aeroflowurology.com website that discussed factors that negatively impact bladder control in individuals with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa based on research.

The author discussed research implying muscle wasting and atrophy caused by malnutrition can lead to weakness in pelvic floor musculature and support structures. This contributes to urinary symptoms, however, also contributes to bowel dysfunction. The musculature around the colon when not used will atrophy and weaken.

Purging behaviors have numerous negative and potentially dangerous effects on the body function of individuals with eating disorders. Vomiting will increase pressure on PFM, pelvic organs, and abdominal musculature. Laxative use will lead to fecal issues such as fecal incontinence and can contribute to increased pressure and trauma on pelvic organs/musculature. Purging will also lead to serious electrolyte imbalances which can lead to organ system dysfunction or failure.

Other medications also influence bowel and bladder function such as diuretics, which are often mis-utilized to lower body weight through the rapid loss of body fluids. Individuals with DM Type 1 may also withhold insulin to result in a diuretic effect. This not only disrupts essential body electrolytes, but it will also lead to dehydration contributing to bowel dysfunction such as constipation. Diuresis of fluids will also increase urinary urgency, frequency, and risk for incontinence.

Constipation may be caused by numerous factors including dehydration, muscle wasting, slow motility, decreased gastric emptying, and poor nutritional intake. Upregulation of the sympathetic nervous system with trauma history, personality traits, and numerous mental health comorbidities such as anxiety, OCD, and depression, play a significant role in constipation. Bowel movement straining places excessive stress on pelvic organs, pelvic musculature, fascia, and suspension structures, as well as the abdominal wall musculature and fascia. Constipation also contributes to urinary dysfunction due to the proximity of pelvic organs and can lead to pelvic organ prolapse.

Hormonal changes due to endocrine dysfunction with eating disorders, such as with AN, BN, and OSFED, can lead to disruptions in body system function. Hormonal disruptions often lead to hypothalamic amenorrhea, reduced levels of important levels of leptin (regulates appetite, energy balance, and metabolism), insulin (regulates blood sugar and is responsible for storage of incoming food as fat/ fuel), incretins (regulates blood sugar by stimulating pancreas to produce insulin), amylin (may contribute to low bone density with AN), plasma sodium and altered osmolarity (may result in nausea, vomiting, energy loss, confusion, seizures, heart, liver, kidney dysfunction). In addition, there are disruptions with other essential electrolytes that can contribute to body organ system malfunction and failure.

As pelvic health rehabilitation providers, we know how to treat pelvic and abdominal dysfunction.

We may, in fact, be the first healthcare professional who asks the important questions or makes insightful observations that illuminate a person’s secret struggle in the darkness. We may be able to lead these individuals to healthcare providers who are skilled in diagnosing, managing, and guiding that individual into the light of recovery. While we do not treat eating disorders, we DO treat the dysfunction caused by eating disorders. So many individuals with eating disorders will benefit from our education and interventions to assist them on their recovery journey.

Join Carole High Gross, PT, MS, DPT, PRPC in Eating Disorders and Pelvic Health Rehabilitation on October 19-20 for a deep dive into the role of pelvic health rehabilitation with individuals with eating disorders. We will discuss the different eating disorders, medical complications, signs and symptoms, screening and observations, interventions, and treatment approaches.

References:

- Abbate-Daga, G., Delsedime, N., Nicotra, B., Giovannone, C., Marzola, E., Amianto, F., & Fassino, S. (2013). Psychosomatic syndromes and anorexia nervosa. BMC psychiatry, 13, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-14[31]

- Abraham, S., Luscombe, G. M., & Kellow, J. E. (2012). Pelvic floor dysfunction predicts abdominal bloating and distension in eating disorder patients. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology, 47(6), 625–631. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365521.2012.661762

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision DSM- 5TR. Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Press. 2022.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Press. 2013.

- Andersen AE, Ryan GL. Eating disorders in the obstetric and gynecologic patient population [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;116(5):1224]. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1353-1367. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c070f9

- Bodner-Adler, B., Alarab, M., Ruiz-Zapata, A. M., & Latthe, P. (2020). Effectiveness of hormones in postmenopausal pelvic floor dysfunction-International Urogynecological Association research and development-committee opinion. International urogynecology journal, 31(8), 1577–1582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04070-0