A recent systematic review published in The Lancet online describes the benefits of using music as a postoperative aid in recovery. Seventy-three randomized, controlled trials were included in the review, and the articles covered the use of music before, during, and after surgery. A wide variety of surgical procedures were represented in the research articles, and included cardiac procedures, mastectomy, urogynecologic and abdominal surgeries, and gastrointestinal surgeries and procedures. Interventions included listening to music with headphones, listening to relaxation training or “therapeutic suggestion.” Many of the studies included a control group with routine care or white noise, headphones without music.

The main results of the research is that use of music reduces postoperative pain, anxiety, and analgesia use, and improves patient satisfaction. The timing of or choice of music listened to in the studies did not significantly affect outcomes. Interestingly, even when patients were given general anesthesia, music was effective. And when patients chose their own music, there was a slight increase in reduction of pain and analgesia use.

How can this information be of use to pelvic rehabilitation providers? Perhaps one of your patients will be heading into surgery. A recommendation for listening to favorite music in the postoperative period could be made. Is music available to your patients in your setting? If so, what kind of music? Is the patient allowed to influence the type of music? Maybe the patient could play a favorite song list from their smart phone, or request a certain time period of music on a music subscription service you may use in the clinic. Regardless of how we use this information, it’s great to be reminded of the potentially positive ways that music can influence healing.

National Public Radio (NPR) recently posted a story on their website that you can listen to if you are interested. For more interesting reads about music and healing, check out the links below:

Psychology Today: Does Music Have Healing Powers?

Scientific American: Music Can Heal the Brain

Carolyn McManus, PT, MS, MA is the author and instructor of "Mindfulness Based Pain Treatment: A Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain". Carolyn is a specialist in managing chronic pain, and has incorporated mindfulness meditation into her practice for more than 2 decades. Today she is sharing her experience by analyzing some of the most foundational research in the field of mindfulness and meditation.

Mindfulness awareness has been described as the sustained attention to present moment awareness while adopting attitudes of acceptance, friendliness and curiosity. (1,2) In patients with persistent pain, mindfulness has shown to reduce pain intensity, anxiety and depression and in improve quality of life. (3,4) Researchers suggest that mindful awareness may work through 4 mechanisms: attention regulation, increased body awareness, enhanced emotional regulation and changes in perspective on self. (5)

Mindfulness awareness has been described as the sustained attention to present moment awareness while adopting attitudes of acceptance, friendliness and curiosity. (1,2) In patients with persistent pain, mindfulness has shown to reduce pain intensity, anxiety and depression and in improve quality of life. (3,4) Researchers suggest that mindful awareness may work through 4 mechanisms: attention regulation, increased body awareness, enhanced emotional regulation and changes in perspective on self. (5)

1. Attention Regulation: In chronic pan populations, improved attention regulation has been suggested to result in less negative appraisal of pain, greater pain acceptance and reduced pain anticipation. (6)

2. Body Awareness: Improved body awareness has been shown to help patients with chronic pain recognize the difference between muscle tension and relaxation, identify early warning signs that precede a pain flare and reduce maladaptive reactions to pain. (7)

3. Emotional regulation: Training in mindful awareness has been shown to enhance emotional regulation, improve mood and reduce anxiety and depression in patients with chronic pain. (6, 7, 8)

4. Changes in Perspective on Self: In a qualitative study, participants with chronic pain reported becoming less identified with their pain condition or diagnostic label. (7) They felt less “fragmented, experienced a greater integration of mind any body and described the experience of wellness even though they had a persistent pain condition.

I constantly see these changes in my patients who learn to be mindful. Empowered with a skillful way to pay attention, they have greater control over the direction of their mind and thoughts and an increase in body awareness that promotes the ability to relax and the self-regulation of their stress reaction. They avoid escalating distressing emotions and experience a renewed feeling of wholeness and well-being. I am delighted to share my training and experience in mindfulness and years of teaching mindfulness to patients in persistent pain through Herman and Wallace continuing education programs.

1. Kabat Zinn, J., 2013. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness. 2nd ed. New York: Bantam.

2. Bishop, S.R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., et al., 2004. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), pp. 230–41.

3. Lakhan, S.E., Schofield, K.L., 2013. Mindfulness-based therapies in the treatment of somatization disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 8(8), e71834.

4. Reiner, K., Tibi, L., Lipsitz, J.D., 2013. Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce pain intensity? A critical review of the literature. Pain Med, 14(2), pp. 230-42.

5. Holzel, B.K., Lazar, S.W., Guard, T., et al., 2011. How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. Perspect Psychol Science, 6, pp. 537–59.

6. Brown, C.A., Jones, A.K., 2013. Psychobiological correlates of improved mental health in patients with musculoskeletal pain after a mindfulness based pain management program. Clin J Pain, 29(3), pp. 233-44.

7. Doran, N.J., 2014. Experiencing wellness within illness: Exploring a mindfulness-based approach to chronic back pain. Qual Health Res, 24(6), pp. 749-60.

8. Song, Y., Lu H., Chen H., et al. Mindfulness intervention in the management of chronic pain and psychological comorbidity: A meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Sci, 1(2), pp.215-23.

An interesting study aimed to objectively answer the following question: Does applying kinesiotape to promote a posterior pelvic tilt improve an active straight leg raise (ASLR) test in women who have sacroiliac joint pain and who habitually wear high-heeled shoes? To explain some of the rationale for the chosen technique and target population, the authors first describe prior research pointing out that use of high heels can lead to an anterior pelvic tilt position and increased lumbar lordosis. This position can slacken the sacrotuberous ligament and therefore reduce the ability of the ligament to create proper form closure, according to the article.

The research included 16 women with a mean age of 23.63. Inclusion criteria is as follows: having a habit of wearing high-heeled shoes (at least 4 times/week for 4 consecutive hours over at least 1 year), and having pain in both sacroiliac joints with the active straight leg raise test (ASLR). Additionally, having symptoms for at least 3 months, no proximal SIJ pain referral to the lumbar spine, and at least 3 of 5 positive SIJ tests (posterior shear test, pelvic torsion test, sacral thrust test, distraction and compression test) were needed for inclusion in the study.

Anterior pelvic tilt was measured using a palpation meter (PALM) before, immediately after application, 1 day after tape application, and immediately after removal of tape. ASLR was measured at same time points. The ASLR was self-scored on a 6-point scale ranging from “not difficult at all”” to unable to perform”. Kinesiotape was applied for a posterior pelvic tilt taping, and the tape was applied in the target position. I-type strips with ~50% of available tension were applied over the rectus abdominis and external oblique muscles. I-type strips with ~75% tension were placed from ASIS to PSIS aiming for mechanical correction of the anterior tilt.

Results of the study indicated a decrease inanterior pelvic tilt, both during and after tape application, and an improved active straight leg raise test. As this was a preliminary study, the results cannot be extrapolated to SIJ pain and dysfunction with other activities than the ASLR test. The degree of anterior pelvic tilt cannot also directly be correlated to sacroiliac joint pain and dysfunction, yet this research is very interesting, and demonstrates a simple method for affecting in the short term a patient’s mechanics as well as reports of function on the ASLR test, a very clinically simple and useful exam.

If you would like to learn more about evaluating and treating dysfunctions related to the sacroiliac joint, join Peter Philip at Sacroiliac Joint Evaluation and Treatment - New Orleans, LA this Sep 12, 2015 - Sep 13, 2015.

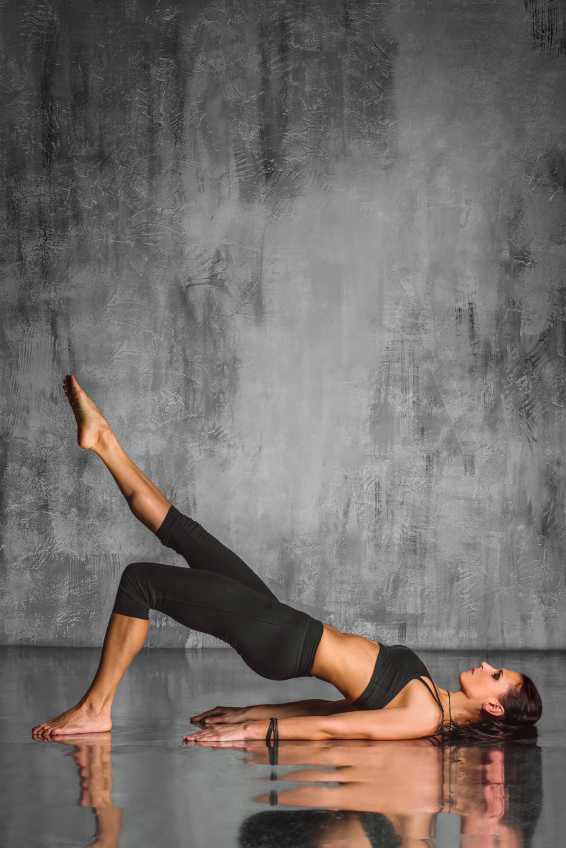

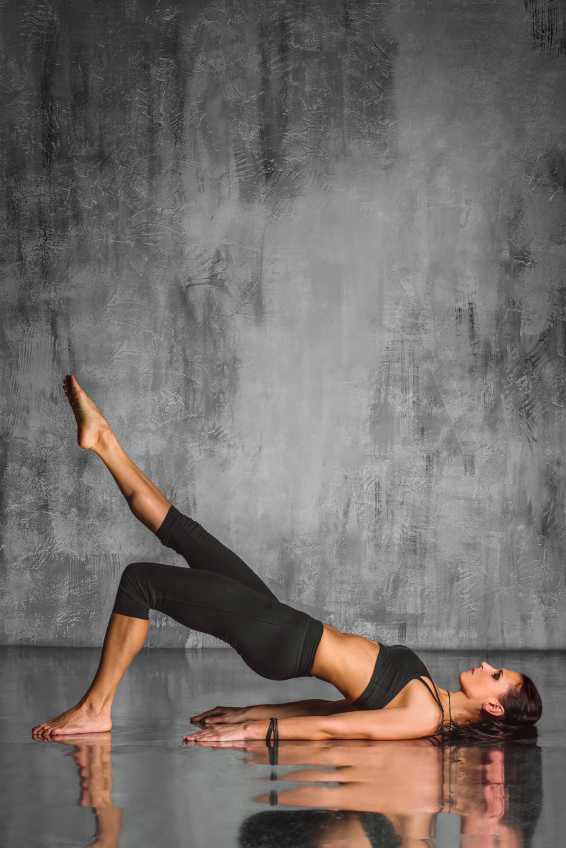

Is there a consensus among physical therapists about the use and perceived effectiveness of Pilates exercise for low back pain? 30 Australian physiotherapists experienced with Pilates exercise were surveyed and asked about Pilates as an indication for low back pain. The results were published in Physical Therapy. Consensus at 100% was reached for benefits, indications, and precautions of Pilates exercise, and only 50-56% for risks and contraindications, respectively. Therapists agreed on indications such as maladaptive movement patterns, poor body awareness, poor flexibility, decreased lumbar spine mobility, poor breathing and postural control.

Is there a consensus among physical therapists about the use and perceived effectiveness of Pilates exercise for low back pain? 30 Australian physiotherapists experienced with Pilates exercise were surveyed and asked about Pilates as an indication for low back pain. The results were published in Physical Therapy. Consensus at 100% was reached for benefits, indications, and precautions of Pilates exercise, and only 50-56% for risks and contraindications, respectively. Therapists agreed on indications such as maladaptive movement patterns, poor body awareness, poor flexibility, decreased lumbar spine mobility, poor breathing and postural control.

The contraindications that were agreed on (but not as strong an agreement as the indications) included pre-eclampsia and unstable fractures. Agreement was reached that participation in Pilates exercise requires caution in the presence of unstable spondylolisthesis or significant lower extremity radiculopathy. The contraindications that were no agreed upon included cancer, severe osteoporosis, significant hypertension, and yellow psychosocial flags.

The physiotherapists did all agree that Pilates may help patients who have chronic low back pain by increasing function and confidence with movement, exercise, and activities, and additionally, that body awareness, postural control, and movement patterns may improve. Potential adverse events that may occur following Pilates exercise (and that were agreed upon) included aggravation of low back pain, or increased muscle tension. In relation to other potential risks of participating in Pilates exercise, inadequate training of instructors and inappropriate exercise prescription was listed. If you would like to learn more about Pilates exercise prescription for specific women’s health issues such as pelvic floor dysfunction, peripartum issues, and perimenopausal issues such as osteoporosis, check out the Institute’s new course on Pilates.

What are the attributes and barriers to care for college-aged women who have pelvic pain? This is a question asked by researchers who published an original article on the topic in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. To complete the study, a random sample of 2000 female students at the University of Florida were sent an online questionnaire. Included in the questionnaire was basic demographic data, general health and health behavior questions, psychosocial factors, measures assessing different types of pelvic pain such as dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, urinary, bowel, or vulvar pain, and information about barriers to care for pelvic pain and quality of life measures. A total of 390 women completed the survey, and the mean age was 23 years old. Most of the women in the sample identified as white, with 9.6% identifying as black or African-American. Most of the respondents had never been pregnant. The chart below lists some of the data.

| Experienced pelvic pain over past 12 months | 73% |

| Dysmenorrhea | 80% |

| Deep dyspareunia | 30% |

| Symptoms with bowel movements | 38% |

| Vulvar pain (including superficial dyspareunia) | 21.5% |

| Of women with pelvic pain, those lacking diagnosis | 79% |

| Of women with pelvic pain, those who have not visited doctor | 74% |

Barriers to receiving care included difficulty with insurance coverage and providers’ “…lack of time and knowledge or interest in chronic pelvic pain conditions.” An interesting finding was that among the women who had pelvic pain, those who were sexually active reported lower scores on physical and mental health. Even among the women without pelvic pain, those who were sexually active reported lower mental health scores.

How can this study encourage us as pelvic rehabilitation providers? Can we reach out to providers and share the potential benefits of pelvic rehab care to decrease the burden on the patient in finding services? It seems that in addition to continually spreading the word that pelvic pain can be eased with rehabilitation efforts, we can provide the interest and knowledge in the subject so that the patient can feel validated and can be instructed in self-management tools.

Over the past 28 years, my pelvic floor has endured at least 20,000 miles of running, including racing on the collegiate level and then completing 10 marathons. Add to the high-impact sport two 8.1 pound natural childbirth deliveries 26 months apart, and you can imagine why I accepted the invitation to blog for this well-respected institute. One of my elderly patients once told me my uterus was going to drop out from so much running (which, thankfully, has NOT happened); however, I have to admit, urinary stress incontinence and frequent urination were unwelcome enough consequences! On the positive side, it all initiated my journey to understanding the pelvic floor.

![By Mike Baird [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](/images/photos/Blog/Female_jogger.jpg)

In 2014, Poswiata et al used the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6) to assess how prevalent stress urinary incontinence may be among elite female skiers and runners. Of the 112 female athletes in the study, 50% reported leaking a small amount of urine. Coughing and sneezing provoked leakage for 45.54% of those women, indicating stress incontinence, and 58.04% of the women in the study reported frequent urination. Are those acceptable statistics? I would have to say no.

Research results can be comforting so athletes can be told they are not alone regarding a quite personal aspect of their lives. When I could supposedly empty my bladder, stand to wash my hands and have to go again, walk down the hall to put on my sneakers and go once again before heading out the door for a run, it was nice to know someone else was probably experiencing the same issue that morning. Just because it is common, though, does not make it “normal.” We are not meant to leak just because we stress our bodies beyond normal ADLs.

A very recent study by Luginbuehl et al (2015 July 21), just published online, attempted to explore the electromyography (EMG) activity of pelvic floor muscles with variable running speeds (7, 9, and 11km/h) over 10 steps. The highest pelvic floor muscle activity was recorded at 11km/h, which would sensibly suggest the muscles produce a greater contraction the faster someone runs. If a runner has developed a decreased ability to activate the pelvic floor muscles, stress urinary incontinence will likely become a highly irritating problem with fast running speeds over time. But how do they know, and where do they go?

Without health practitioners trained in rehabilitation of pelvic floor dysfunctions, consider how chronic an issue urinary stress incontinence would be for a large athletic population. So many women (and men) do not even recognize their leakage or frequent urination as treatable “issues” and never mention them to anyone. Often times, we are treating an athlete for a hip or lumbar injury and purposefully yet discretely have to ask the right questions and then educate the patient how some of their symptoms are secondary to pelvic floor deficits. Someone has to explain what is normal, and, better yet, someone HAS to make an effort to fix what is “broken” and restore the pelvic floor to a higher level of function. With the proper training, perhaps that someone can be you.

References:

1. Poświata, A., Socha, T., & Opara, J. (2014). Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence in Elite Female Endurance Athletes. Journal of Human Kinetics,44, 91–96. doi:10.2478/hukin-2014-0114.

2. Helena Luginbuehl, Rebecca Naeff, Anna Zahnd, Jean-Pierre Baeyens, Annette Kuhn, Lorenz Radlinger (2015 July 21). Pelvic floor muscle electromyography during different running speeds: an exploratory and reliability study. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3816-9.

An article promoting the beneficial role of a thorough clinical assessment was published last year in the Scandinavian Journal of Urology, and although the article is directed to medical providers, serves as an excellent summary for pelvic rehabilitation providers. Doctors Quaghebeur and Wyndaele describe a “four-step plan” that can help direct treatment efficiently, and that emphasizes the muscular and neurologic systems as potential referral sources. While you may not be surprised about several of the steps, you may find this article to be a useful tool, particularly for the terrific chart about neuralgia-type pain that you can find in the linked article.

Step 1 should include history taking with attention to information about the following:

Step 1 should include history taking with attention to information about the following:

- urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia

- bowel habits

- sexual complaints and quality-of-life impact

- pain description with significant detail

- use of questionnaires

Step 2 emphasizes review of prior assessments and reports, including:

- imaging (x-rays, MRI, CT)

- lab work

Step 3 involves a thorough clinical assessment. This includes a neurologic assessment of the lumbosacral plexus, with evaluation of motor and sensory functions as well as reflexes. The nerves suggested for testing are the sciatic, iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, obturator, lateral cutaneous femoral, perineal and dorsal, and the medial, lateral, and inferior cluneal nerves. (An excellent chart listing each of these nerves and their dynamic tests is included in the article.) Of note in the chart is the lack of neurodynamic tests for the deep peroneal nerve, pudendal, perineal, dorsal nerve of the clitoris or penis, and the interior cluneal- these can be tested for symptom reproduction with direct palpation according to the authors. Other Step 3 tests are listed below.

- neurodynamics tension testing and nerve palpation

- EMG testing if needed

- evaluation for hernia (abdominal, inguinal, or femoral)

- exam of external genitalia (rash, secretion, abscess, fistula, atrophic disorders, signs of trauma, palpation)

- rectal and/or vaginal exam

Step 4 involves an extensive musculoskeletal system examination. This includes the spine, pelvic girdle, muscles, tendons, and pain points.

- spinal mobility (palpation, AROM, PROM)

- joint play of SI joints, pubis and sacrococcygeal joints

- muscular pain or other soft tissue pain reproduction

The physicians recommend a multidisciplinary team of providers including physical therapy. The true value of this article, from a rehabilitation standpoint, may be the emphasis on a thorough musculoskeletal examination as well as attention to recognizing neuralgias. We might utilize an article such as this to dialog with medical providers, or to assess our own “thorough” list of examination techniques. Herman & Wallace offers several courses which can benefit the practitioner seeking to gain new evaluation techniques. "Manual Therapy for the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip Complex" is a great option which will be available this October 17-18 in beautiful Napa, CA.

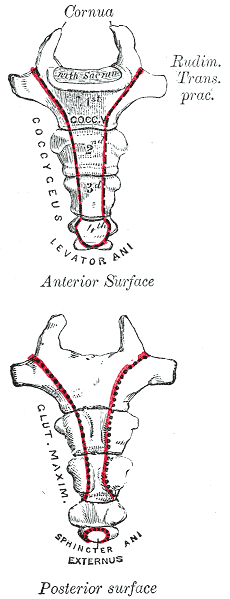

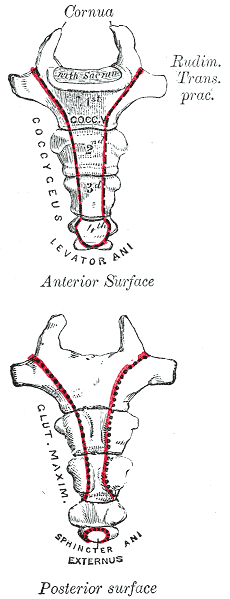

Herman & Wallace faculty member Lila Abbate instructs several courses in pelvic rehabilitation, including "Coccyx Pain, Evaluation and Treatment". Join Lila this October in Bay Shore, NY in order to learn evaluation and treatment skills for patients with coccyx conditions.

Case studies are relevant reading for physical therapists. Reviewing case studies puts you into the writer’s brain allowing you to synthesize your current knowledge of a particular diagnosis taking you through some atypical twists and turns in treating this particular patient type. In JOSPT, August 2014, Marinko & Pecci presented a very well-written case study of two patients with coccyx pain. By then, I had already written my Coccyx course and couldn’t wait to see what the authors had written. I eagerly downloaded the article to see another’s perspective of coccyx pain and their treatment algorithms, if any, were presented in the article. How were the author’s patients different than mine? What exciting relevant information can I add to my Coccyx course?

I believe that coccyx pain patients have more long-standing pain conditions than other patient types. For the most part, the medical community does not know what to do with this tiny bone that causes all types of havoc in patients’ pain levels. Sometimes treating a traumatic coccydynia patient seems so simple and I am bewildered as to why patients are suffering so long - and other times, their story is so complex that I wonder if I can truly help.

The longer I am a physical therapist, the more important has the initial evaluation become. Our first visit with the patient is time together that really helps me to create a treatment hypothesis. This examination helps me to put together an algorithm for treatment. I now hear their story, repeat back their sequence of events in paraphrase and then I ask: do you think there is any other relevant information, no matter how small or simple, that you think you need to tell me? Some will say, I know it sounds weird, but it all started after I twisted my ankle or hurt my shoulder or something like that. I assure them that we have the whole rest of the visit together and they can chime in with any relevant details. Determining the onset of coccyx pain will help you gauge the level of improvement you can expect to achieve. Coccyx literature states that patients who have coccyx pain for 6 months or greater will have less chance for resolution of their symptoms. However, none of the literature includes true osteopathic physical therapy treatment, so I am very bias and feel that this statement is untrue.

The coccyx course is a very orthopedically-based which takes my love of manual, osteopathic treatment and combines it with the women’s health internal treatment aspects so that we are able to move more quickly to get patient’s back on the path to improved function and recovery. The course looks at patients from a holistic approach from the top of their head down to their feet. In taking on this topic, I couldn’t do it without honing into our basic observation skills, using some of my favorite tools in my toolbox: Hesch Method, Integrated Systems Model, and traditional osteopathic and mobilization approaches mixing it with our internal vaginal and rectal muscle treatment skill set.

Marinko LN, Pecci M. Clinical decision making for the evaluation and management of coccydynia: 2 case reports. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Aug; 44(8): 615-21.

The research on pelvic pain and specifically on sexual dysfunction has focused on heterosexual women, leaving a large gap in the clinically-based evidence. A study published last year in the Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy aimed to narrow this gap by studying the characteristics of vulvar pain in women in a variety of relationships. The associations between qualities such as love and communication were evaluated in relation to the participants' perceptions of how pain influenced their relationships. Within the research report, the authors establish that pelvic pain commonly causes pain and limitation with sexual function, and that queer women (defined in their work as women who identify as something other than heterosexual) also experience pain with sexual function.

"Of the 839 women, 31% reported genital pain, with 12% of the women with genital pain in a same-sex relationship, 67% in a mixed-sex relationship, and 21% being single"

The women in the study provided information about demographics, experiences of genital pain and pain characteristics. They completed surveys including the Dyadic Trust Scale (measures trust in a close relationship), the Rubin Love Scale (assesses level of romantic love), and the Communication Subscale of Evaluation and Nurturing Relationship Issues, Communication and Happiness Marital Satisfaction Scale (measures level of communication). Participants' average age was 25, and of the 77% who were in a relationship, most (60%) were in a mixed-sex relationship. Average length of relationships was 3 years, with nearly 84% of the women being white with some level of higher education.

Of the 839 women, 31% reported genital pain, with 12% of the women with genital pain in a same-sex relationship, 67% in a mixed-sex relationship, and 21% being single. Of the 260 women reporting genital pain, 39% identified as heterosexual, 15% identified as lesbian, and 46% identified as bisexual. The most common pain locations reported were inside the vagina (48%), in the pelvis or abdomen (45%), at the vaginal opening (39%), and 21% of the women reported global vulvar pain. From the data, the authors also report that women in same-sex relationships were likely to report that tampon insertion was painful.

The authors point out that challenges to healing for women who identify outside of heterosexual are many, and can include:

- homonegativity and heterosexism at a medical provider's office

- failure to disclose sexual identity due to fear of negative interaction

- fear that a symptom is linked to a sexual practice

- being in an unsupportive relationship or having poor adjustment within relationship

The limited research on sexual pain in women in same sex relationships has highlighted strengths within the relationships as well. Women in same sex relationships have been noted to have more effective communications skills, which may in turn foster better understanding of conditions such as pelvic pain. The authors concluded that while the characteristics of vulvar pain were similar across groups, there was a difference in the perception of pain impact on relationships. Better communication for same-sex couples and more love for mixed-sex couples was positively associated with impact on relationship. Of the women reporting pain, nearly half of the participants indicated that the pain negatively impacted their relationship in general, and 64% reported that the pain interfered with sexual health.

This type of research provides insight for pelvic rehabilitation clinicians and adds to our data base of considerations when working with women. The truth is that most of us were not provided adequate training in how to evaluate and manage issues of sexual health, nor were we provided with the means to value our own sexuality as a normal and healthy part of being. This lack requires education to fill in our own gaps, so that we can be of best service to our patients. If we are able to be present and nonjudgmental, our patients can in turn share openly and provide information that can direct best care. Holly Herman, co-founder of the Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute, offers a 2-day course in Sexual Medicine, so that providers can learn more about healthy sexuality as well as how to dialog with our patients.

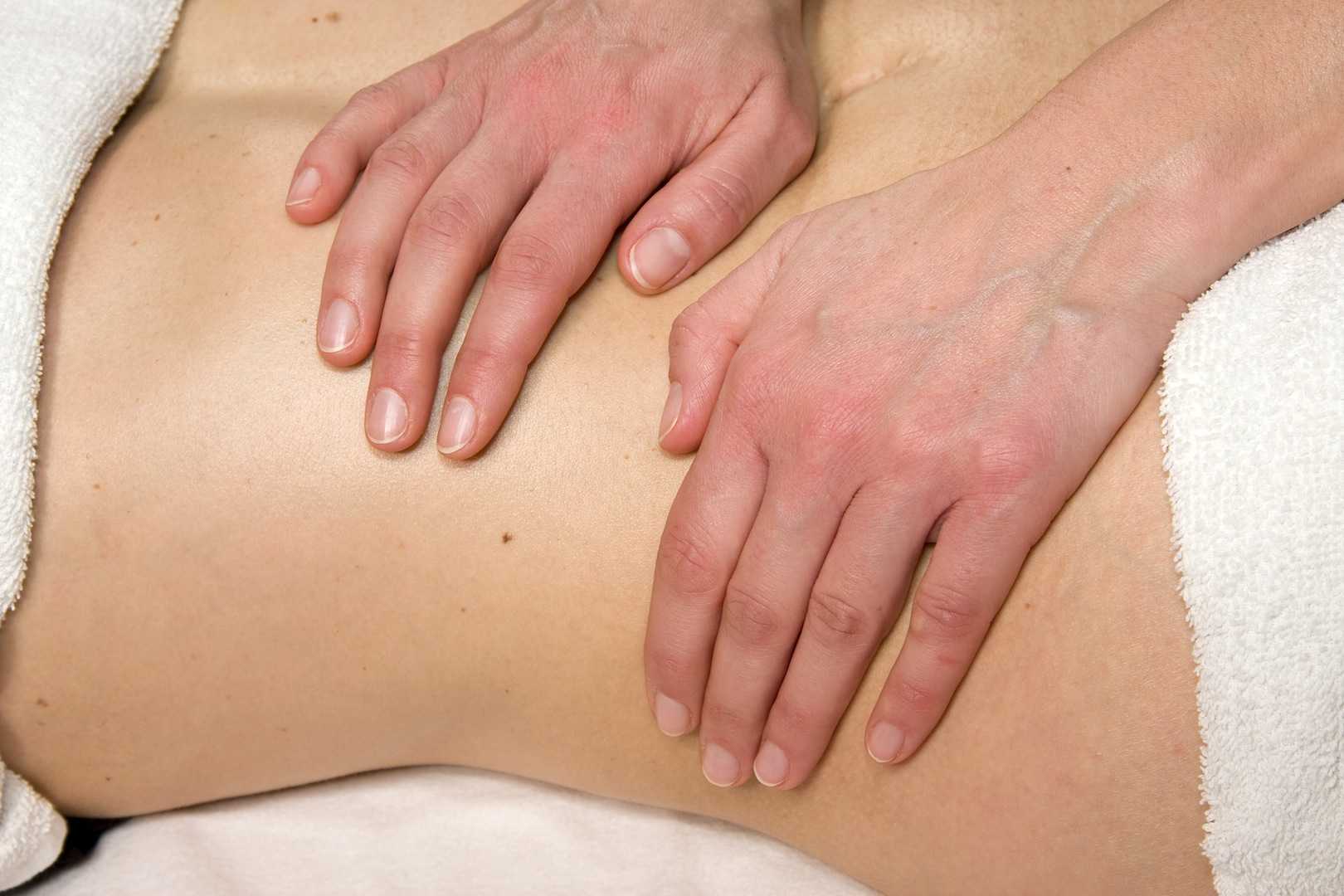

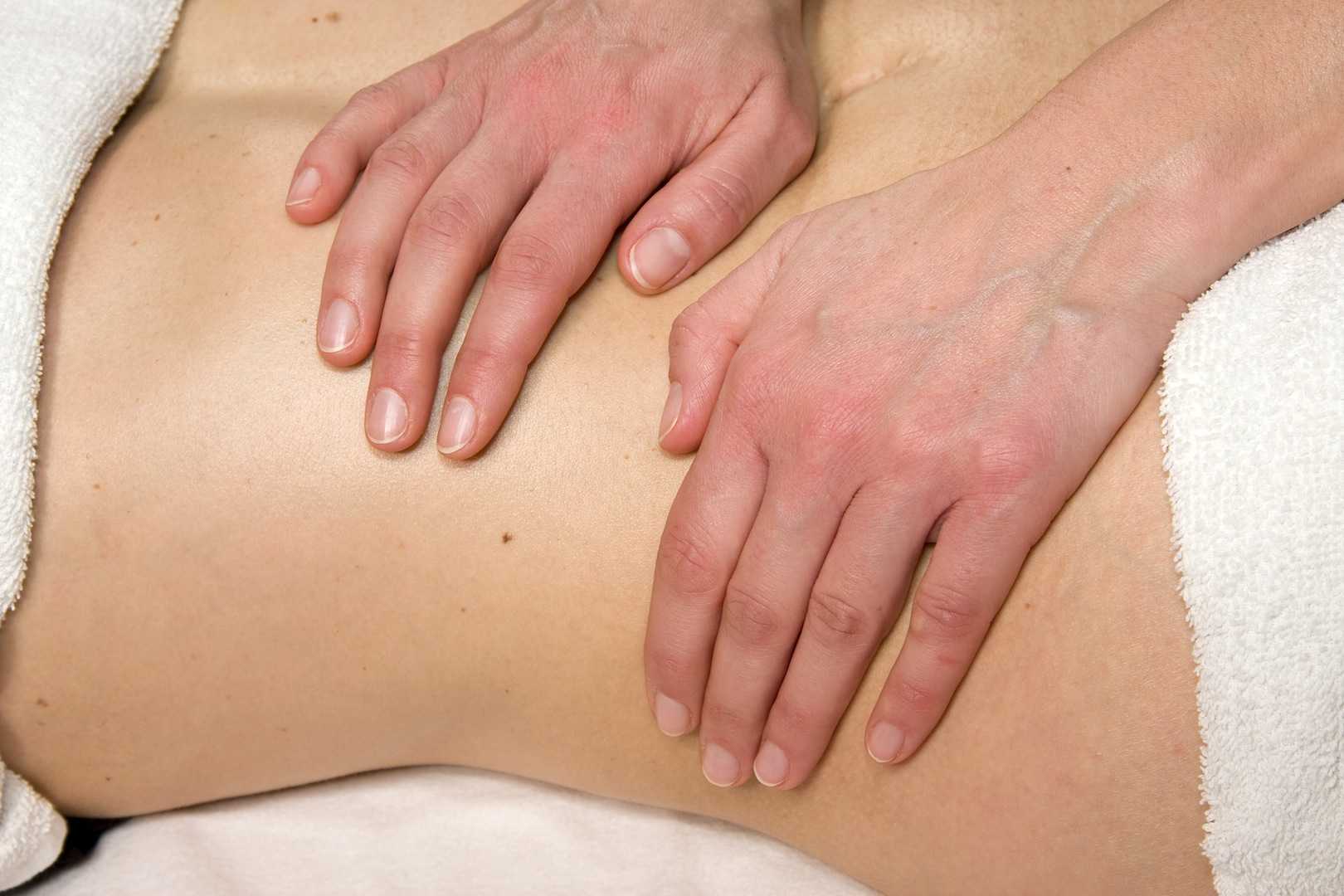

Visceral therapy is increasingly used by manual therapists, and research continues to emerge that attempts to explain the underlying mechanisms of the techniques. A study published in the Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies in 2012 reports on the effects of visceral therapy on pressure pain thresholds. Osteopathic visceral mobilization was applied to the sigmoid colon in 15 asymptomatic subjects. Pressure pain thresholds were measured at the L1 paraspinal muscles and 1st dorsal interossei before and after intervention. Pressure pain thresholds at the level assessed improved significantly immediately following the visceral mobilization. The effect was not found to be systemic. Hypoalgesia, therefore, may be a mechanism by which visceral mobilization affects patients who are treated with this technique.

Another research study that aimed to assess the effects of visceral manipulation (VM) on low back pain found that the addition of VM to a standard physical therapy treatment approach did not provide short term benefits. However, when the 64 patients were reassessed at 2, 6, and 52 weeks following treatment, the patients in the group with visceral manipulation were found to have less pain at 52 weeks. The patients were randomized into 2 equal groups and were provided physical therapy plus a placebo visceral treatment or a visceral treatment in addition to physical therapy. The authors propose that there may be long-term benefits of including visceral therapy in rehabilitation approaches.

If you would like to learn more about visceral techniques as well as theory and clinical application, check out the schedules for Ramona Horton's Visceral Mobilization 1 (VM1): The Urologic System, and Visceral Mobilization 2 (VM2): The Reproductive System. The first opportunity to take VM1 is in November in Salt Lake City and VM2 is scheduled in September in Ohio.