Pain associated with menstruation is known as dysmenorrhea, and more than half of women have pain related to their period for 1-2 days per month, according to The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Primary dysmenorrhea is related to menstruation, and often begins within a short period of time once menses occurs, whereas secondary dysmenorrhea is often related to a condition within the reproductive tract such as endometriosis or fibroids. In the medical office, a medical history, a pelvic exam, and possibly an ultrasound or laparoscopy will be completed. Treatment may include medications such as NSAIDs which target the prostaglandins that often lead to symptoms of dysmenorrhea, birth control pills, or surgeries.

A recent literature review asked if physiotherapy can help with symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea. Of the articles reviewed, 186 were chosen, and included a range of articles from descriptive, experimental studies to prospective, randomized controlled studies. A variety of interventions and approaches were included in the review, such as TENS, abdominal massage, acupuncture, cryotherapy and thermotherapy, connective tissue, Pilates, and belly dance. All of the approaches demonstrated some therapeutic benefit, either in response to the immediate application of the intervention, or up to a few months after the intervention was applied or instructed.

This literature review echoes a prior systematic review that evaluated the effectiveness and safety of acupressure, acupuncture, aspirin, behavioral interventions, oral contraceptives, and other supplements, procedures, and complementary and alternative medical interventions. Click here to view the full-text article. In that particular review, the authors reported the following:

- high-frequency TENS reduces pain (but less so than ibuprofen)

- acupressure may be as effective as ibuprofen

- topical heat may be as effective as ibuprofen and more effective than paracetamol

The bottom line from this research should be that we as pelvic rehabilitation providers need to help patients address pain and symptoms from dysmenorrhea. Clearly, there are many pathways to achieve symptom reduction, and some, such as TENS or topical heat, are easily carried out on an independent basis. How are you reaching adolescent girls who may develop primary dysmenorrhea? In clinical practice, talking with their parents, or reaching out at the community level to schools, churches, camps, gyms, or coaches may provide an opportunity to provide education and help. If you would like to learn more about myofascial release techniques for the abdomen and pelvis, check out the Myofascial Release for Pelvic Dysfunction continuing education course taking place next month in Illinois!

The following comes to us from faculty member Allison Ariail. Allison teaches several courses for the Institute, her next one being Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging in Baltimore, MD on June 12-14. There is still room, so sign up today!

Living in Colorado, I come across a lot of individuals who are avid runners, cyclists, or triathletes. Even with a higher level of fitness, these individuals will at times have back pain. What is going on in these physically fit, strong individuals? This is what Rostami et al.[1] set out to determine in their recent study. Using ultrasound imaging, they measured the thickness of the transversus abdominis, internal oblique, external oblique, and the cross sectional area of the multifidus while laying down as well as while mounted on a bicycle. They also measured the back strength, endurance, and flexibility of off-road cyclists with and without back pain. Fourteen professional competitive off-road cyclists with low back pain were compared to 24 control. Results showed a significantly thinner transversus abdominis, and cross sectional area of the multifidus muscle in the cyclists with back pain. There was no significant difference found in flexibility or isometric back strength between the two groups. However the cyclists with low back pain demonstrated decreased endurance in back dynamometry with 50% of their maximum isometric back strength.

The results of this study are consistent with other studies that examined less athletic individuals; thinner transverseus abdominis, and smaller multifidus muscles. This further reinforces the training of the local stabilizing muscles. What does this training method consist of? Learning to isolate each of the local stabilizing muscles; the transversus abdominis, the multifidus, and the pelvic floor muscles. Once a patient is able to isolate a contraction, challenge the muscles by holding a contraction while breathing normally, or holding the contraction while performing motor tasks such as Sahrmann’s exercises. Progress the patient so they are able to perform contractions in weight bearing positions and co-contractions of the muscles. Finally, progress the patient to maintaining co-contractions during functional activities and exercise activities. This will improve stability of the back and pelvis as well as decrease the pain experienced by the patient.

Even patients with higher levels of activity and physical fitness can benefit from a program such as this one. I have used this treatment protocol using ultrasound imaging to confirm and train the local stabilizing muscles on individuals who are both active as well as with individuals not able to participate in as much physical activity. Each and every patient has made gains, even patients who already had a higher level of activity and sports participation such as cyclists, runners, and triathletes. It is rewarding to see all patients make gains and improvements!

[1]Rostami M, Ansari M, Noormohammadpour P et al. Ultrasound assessment of trunk muscles and back flexibility, strength and endurance in off-road cyclists with and without back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2014; Nov.

Today’s contribution to the Pelvic Rehab Report comes from Allison Ariail, the instructor for Herman & Wallace’s Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging courses. Join Allison and others this June 12-14 at Rehabilitative Ultra Sound Imaging: Women's Health and Orthopedic Topics - Baltimore, MD!

Is an Ultrasound that provides images of the pelvic floor and other deep musculature a cool gadget to have in the office or something that is truly essential? That depends on who you are asking! If you know how to use Ultrasound imaging properly and market yourself and your practice accordingly, it can become a tool that is not only fun to have and handy to use clinically, but also essential to providing your most efficient and thorough care!

Using an ultrasound (US) machine allows you to view the deeper musculature to assess how the muscles are functioning. The most common muscles assessed with US imaging are the transverse abdominis, the multifidus, and the pelvic floor. The patient then can use what is seen on the US screen as biofeedback to retrain their strategy and timing of recruitment. The therapist can also assess the patient’s ability to activate and maintain a contraction in various positions and even during motor tasks as well. This type of biofeedback is not only useful for pelvic floor patients, but is also important for patients with back and sacroiliac joint pain. Research is showing that using this type of stabilization program is making a difference in athletes. Julie Hides has published two articles recently showing that this type of stabilization program has helped with low back pain in professional cricket players, as well as to decrease the rate of lower extremity injury in Australian professional football players. (1,2) (see my post on The Local Stabilizing Muscles and Lower Extremity Injury.

You may be saying to yourself that you can save a lot of money and just palpate the transverse abdominis (TA), and the multifidus. However I would ask you… are you really feeling a transverse abdominis contraction, or some of the internal obliques? I have had 2 patients referred to me from very capable therapists that I respect and look up to. They were referred to me due to a lack of progress in their treatment. The therapist was addressing a local stabilization program, but their back pain was not getting better. To their credit, the therapist was able to train both patients to perform a proper TA contraction in supine, however one patient was unable to hold a contraction beyond 1 second, and another one was not able to activate it in sitting, or standing. This would explain why they were not progressing with respect to their pain. After treating each patient for 1 or 2 visits using US imaging, and sending them back to their referring therapist, they made rapid progress. Both therapists were so convinced on the usefulness of US imaging that they both went out and bought a machine to use in their clinic. Additionally, you would be surprised how many physical therapists (I can’t count the number on two hands anymore) I have seen that think they are properly performing a TA contraction and want to see how they are doing on the US. However, once we used the US imaging to assess their TA contraction, they realized they were overcompensating with their internal obliques. This is with physical therapists who have more knowledge than the general public regarding the importance of these muscles and how to activate them!

If you are knowledgeable in using ultrasound imaging, you open your doors to a number of possible patients you may not be currently accessing as referrals. There are numerous women and men who would like to receive treatment for pelvic floor weakness issues, but do not want to have to disrobe each treatment. Using ultrasound imaging is a wonderful option for these patients. It also is a way to treat younger patients that you have not been able to treat in the past as well (I would recommend taking the Pediatric Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction course prior to treating pediatric patients). By using ultrasound imaging you not only gain an edge over your competing clinics that specialize in pelvic floor therapy, but you can gain an edge for back patients and sacroiliac joint patients as well. For the reasons I stated above when discussing a stabilization program centered on the use of US imaging, you could become very busy with referrals from spine surgeons, and ortho docs. In my office we have six therapists trained in using ultrasound imaging and two ultrasound machines. One of our most limiting factors is not the lack of patients to use ultrasound on, but that we only have two US units available to use! We have several spine physicians that send all of their patients to us because they have seen the difference using ultrasound imaging and the stabilization program can make in patients’ lives. We are eagerly awaiting a third machine and know it will be immediately used and allow us to further grow our clinic.

Now you may be saying, “Yes this would be handy but the pricing makes it impossible!” I would say think outside of the box! Some machines are going down in price making them more affordable. Plus, the settings we as therapists use are pretty basic, so we do not need to purchase a unit with a lot of bells and whistles that makes it more expensive. However there are other ways to acquire a unit other than purchasing one brand new. You could look into the price of refurbished units or look to your referring physician groups that you have a good relationship with. You may be surprised to find out how much physician’s offices get for machines when they are upgrading; hardly anything! If you work for a hospital system you may be able get the old machine transferred to your department for no cost to you! Or if you work in a private practice, you could offer to match the little amount the office would get from the vendor when upgrading. I guarantee you it would not be as much as a new unit. You also might be able to share a unit with another department, office, or clinic. In the past, I have shared ultrasound units with a surgical department, and a gynecology office. I would use the ultrasound some days of the week, and they would other days of the week. It worked out well! There are a lot of possibilities of ways to acquire an ultrasound unit if you think outside of the box! It may take a little effort coordinating things in order to get an US unit, but with proper knowledge, proper marketing, and word of mouth your business will grow and you will not regret the decision to invest in your practice!

Join me to discuss more ideas of how to use US imaging to grow your practice in both clinical skill as well as business growth this June in Baltimore!

1. Hides, Stanton, Wilson et al. Retraining motor control of abdominal muscles among elite cricketers with low back pain. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010; 20: 834-842.

2. Hides JA, Stanton WR. Can motor control training lower the risk of injury for professional football players? Med Sci Sports Exec. 2014; 46(4): 762-8.

This post was written by Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC. You can catch Jennafer teaching the Pelvic Floor Level 2B course this weekend in Columbus.

"I hate my vagina and my vagina hates me. We have a hate- hate relationship'" said my patient Sandy (name has been changed) to me after treatment. Sandy's harsh words settled between us. I understood perfectly why she might feel this way. I have been treating Sandy on and off for four years. She has had over fifteen pelvic surgeries. Her journey started with a hysterectomy and mesh implantation to treat her prolapsed bladder. She did well for several months and then her pain began. Her physician refused to believe that her pain was coming from the mesh. This pattern was repeated for several years as Sandy tried in vain to explain her pain to her medical providers. She was told her pain was all in her head and put on psych meds. Finally, five years later, Sandy found her way to an experienced urogynecologist who recognized that Sandy was having a reaction to the mesh from her prolapse surgery. It turns out that Sandy's body rejected the mesh like an allergen. Her tissues had built up fibrotic nodules to protect itself from exposure to the mesh. It has taken years and multiple operations to remove all the mesh and all the nodules. Of course then Sandy's prolapse recurred as well as her stress incontinence and she recently had surgery to try to give her some support. In PT we attempted to manage her pain, normalize her pelvic floor function, strengthen her supportive muscles and fascia. Due to years of chronic pain, her pelvic floor would spasm so completely internal work was not possible. Sandy began to also get Botox injections to her pelvic floor and pudendal nerve blocks. She uses Flexeril, Lidocaine and Valium vaginally three times a day to manage her chronic pelvic pain. She is on disability because she cannot work. Later this month Sandy will have her 16th surgery to remove a hematoma caused by her previous surgery and another nodule that we found in her left vulva. Sandy is the most complicated case of mesh complication that I have seen in my practice, however I regularly see women who have had problems with mesh that we manage through PT and also women that have had mesh removal. No one expects to have complications with their surgery and when they do it can be life altering.

In a recent review of the literature surrounding mesh complications Barski and Deng cite that over 300,000 women in the US will undergo surgical correction for stress incontinence (SUI) or pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Mesh related complications have been reported at rates of 15-25%. Mesh removal occurs at a rate of 1-2%. Mesh erosion will occur in 10% of women. There are over 30,000 cases in US courts today related to pain and disability due to mesh complications. The authors looked at mesh complication statistics from studies concerning three surgical procedures: mid urethral slings, transvaginal mesh and abdominal colposacropexy .

The authors note there are sometimes reasons why mesh goes wrong: it is used for the wrong indication, there could be faulty surgical technique, and the material properties of mesh are inherently problematic for some women. Risk factors in patient selection are previous pelvic surgery, obesity and estrogen status. There are several types of complications described: trauma of insertion, inflammation from a foreign body reaction, infection, rejection, and compromised stability of the prosthesis over time. With mid urethral slings there were also several other complications listed such as over active bladder (52%), urinary obstruction (45%), SUI (26%) mesh exposure (18%) chronic pelvic pain (18%). For transvaginal mesh, reported rate of erosion was 21%, dysparunia 11%, mesh shrinkage, abscess and fistula totaled less than 10%. Transvaginal obturator tape was noted to be traumatic for the pelvic floor. Infections that might occur in the obturator fossa require careful and through treatment. Of women who have complications 60% will end up requiring surgical removal. It is imperative to find a surgeon who is experienced and skilled with this procedure as complete excision can be difficult and there are risks of bleeding, fistula, neuropathy and recurrence of prolapse and SUI. After recovery, 10-50% of women who have had excision will have another surgery to correct POP or SUI.

As pelvic health physical therapists we are strategically poised to both help women manage SUI and POP conservatively. We also have the skills needed to help rehabilitate women dealing with complications from mesh, either to avoid removal or after removal. Our job goes beyond the physical too, often helping women cope with the emotional toll that can parallel her medical journey. At PF2B we will discuss conservative prolape management and give you tools to help patients cope with chronic pain. Would love to see you there.

This post was written by H&W instructor Elizabeth Hampton. Elizabeth will be presenting her Finding the Driver course in Milwaukee in April!

One of the most consistent questions that we hear at the Pelvic Floor 2B course is, “How do you choose between a pelvic floor and a musculoskeletal exam during your first visit with a pelvic pain client?” The answer depends on a number of factors, which include your clinical reasoning, toolbox, the client’s presentation, the clinical specialty, and expectations of the referring provider as well as the expectations of the client. It can be stressful to imagine gathering a detailed history, testing, client education and a home program within the first visit! Now that we have less time and total visits to evaluate and treat these complex issues, it can be overwhelming to know where to start.

Chronic pelvic pain has multifactorial etiology, which may include urogynecologic, colorectal, gastrointestinal, sexual, neuropsychiatric, neurological and musculoskeletal disorders. (Biasi et al 2014) Herman and Wallace faculty member, Elizabeth Hampton PT, WCS, BCB-PMD has developed an evidence based systematic screen for pelvic pain that she presents in her course “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain”. “There are a number of extraordinary models that exist for treatment of pelvic pain including Diane Lee’s Integrated System of Function, Postural Restoration Institute, Institute of Physical Art and more,” states Hampton. “However, regardless of the treatment style and expertise of the clinician, each clinician should be able to perform fundamental tissue specific screening. If a client has L45 discogenic LBP with segmental hypermobility into extension, femoral acetabular impingement, urinary frequency > 12/day as well as constipation contributed to by puborectalis functional and structural shortness, all clinicians should be able to arrive at the same fundamental findings during their screening exam. The driver of the PFM overactivity(3) needs to be explored further as local treatment alone (biofeedback and downtraining) will not resolve until the condition causing the hypertonus is found and treated.” Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain is a course that models a comprehensive intrapelvic and extrapelvic screening exam with evidence based validated testing to rule out red flags, understand key factors in the client’s case as well as develop clinical reasoning for prioritizing treatment and plan of care. The screening exam complements any treatment model as it identifies tissue specific pain generators and structural condition, which will lead the clinician to follow their clinical reasoning and treatment model. Once the fundamentals are established, the clinician can move beyond screening and drill down into treatment of key factors which may include specific muscle gripping patterns, arthokinematic assessment and respiratory evaluation and retraining, among others.

Co-morbidities are common in pelvic pain are well documented (1, 2) and clinically these multiple factors are the reason pelvic pain is complex to evaluate and treat. Intrapelvic (urogynecologic, colorectal, sexual) as well as extrapelvic (orthopedic, neurologic, psychological and biomechanical clinical expertise) are required for skilled evaluation and treatment of this population. It is precisely this complexity, which makes working with pelvic pain clients challenging and extraordinarily rewarding. Physical therapists are uniquely skilled to put all of the puzzle pieces together in these complex clients. Finding the Driver is being offered twice in 2015: April 23-25, 2015 at Marquette University and again in the fall. Check Herman Wallace.com for further details.

1. Chronic pelvic pain: comorbidity between chronic musculoskeletal pain and vulvodynia. Reumatismo: 2014 6;66(1):87-91. Epub 2014 Jun 6. G Biasi, V Di Sabatino, A Ghizzani, M Galeazzi

2. http://www.jhasim.net/files/articlefiles/pdf/XASIM_Master_5_6_p306_315.pdf

3. IUGA/ICS Terminology for Female Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.iuga.org/resource/resmgr/iuga_documents/iugaics_termdysfunction.pdf

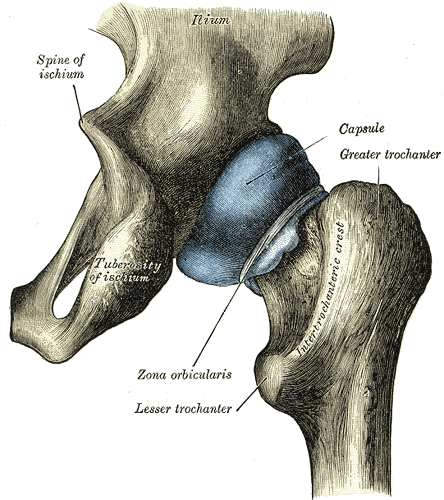

An article appearing this year in Arthroscopy details a systematic review completed to determine if asymptomatic individuals show evidence on imaging of femoroacetabular impingement, or FAI. Cam, pincer, and combined lesions were included in the results. To read some basics about femoroacetabular injury, click here. Over 2100 hips (57% men, 43% women) with a mean age of 25 were studied. (Only seven of the 26 studies reported on labral tears.) The researchers found the following prevalence in this asymptomatic population:

Cam lesion: 37% (55% in athletes versus 23% in general population)

Pincer lesion: 67%

Labral tears: 68%

Mean lateral and anterior center edge angles: 30-31 degrees

The authors conclude that femoroacetabular impingement tissue changes and hip labral injury are common findings in asymptomatic patients, therefore, clinicians must determine the relevance of the findings in relation to patient history and physical examination. Because hip pain is a common comorbidity of pelvic pain, knowing how to screen the hip joint for FAI or labral tears, rehabilitate hips with joint dysfunction, and help someone return to activity following a hip repair is valuable to the pelvic rehabilitation therapist.

As the athletic population may have increased risk of hip injuries due to overuse, traumatic injury, or vigorous activity, being able to address dysfunction in both high level and less active patients is necessary. Herman & Wallace faculty member Steve Dischiavi has developed a course rich in athletic examples and including education about activating fascial systems in various planes. If you are ready to step up your game related to Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis, check out this continuing education course taking place next in Durham, North Carolina in May.

In patients who failed to respond to biofeedback therapy alone for anismus, authors in this study reported a beneficial, although temporary, effect of using botulinum toxin type A injection (BTX-A injection) to the puborectalis and external sphincter muscles. Anismus is more commonly referred to as dyssynergic defecation, or an inability to properly lengthen the pelvic floor muscles during emptying of the bowels. 31 patients who had been treated with and failed "simple biofeedback training" were then treated with BTX-A injection followed by biofeedback training. 18 males and 13 females with a mean age of 50 and a mean duration of constipation of 5.6 years were diagnosed with defecation dysfunction, or anismus. Diagnosis of animus was made using anorectal manometry, balloon expulsion test, surface electromyography (EMG) of the pelvic floor, and defecography.

Pelvic floor muscle training included biofeedback therapy consisting of intra-anal surface EMG and electrotherapy (although the way the methods are described make determining if both EMG and electrotherapy were completed with internal sensors difficult). Treatment occurred 1-2 times/day for 30 minutes per session (15 minutes of electrotherapy and 15 minutes of biofeedback). Frequency of the electrotherapy was 10 Mz, 10 seconds of "considerable sensation without…pain" and 10 seconds of rest. During biofeedback sessions, pelvic muscle strengthening and relaxation was also instructed. Therapy occurred for up to one month, and patients were instructed to continue with therapeutic exercises at home. The researchers followed up one month after the injection and therapy, and 6-12 months after intervention by telephone.

The subjects in this study suffered from difficult and incomplete evacuation, use of laxatives, and chronic straining during defecation. The repeated measures for diagnostic criteria that were completed after intervention found improvements in the subjects' resting anal canal pressures and with the balloon expulsion test and constipation scoring system. The authors also reported adverse effects of BTX-A injections including fecal incontinence. Conclusions of the article include that the botox injections were considered a temporary treatment for defecation dysfunction, whereas the botox injection combined with pelvic floor biofeedback training is "a more valid way to treat."

What is missing from this study? Manual therapy, muscle coordination retraining in combination with abdominal wall activation, and functional training related to positioning. While the authors suggest that injections should be used with biofeedback training, the potential negative effects of botox injections cannot be overlooked. Infection, pain, and bleeding are complications that have been highlighted in the literature, and in this study, fecal incontinence (although reported as mild) occurred. The research design appears to fail to recognize the chronic tension and holding pattern of the pelvic floor muscles, and unless the goal of repeated contractions is to elicit a contract/relax effect, the pelvic floor strengthening per se does not align with the ideal therapeutic goal, which should be to correct the dyssynergic pattern of defecation. Relaxing the pelvic floor muscles is not the same as a functional bearing down or lengthening of the pelvic floor involved in defecation. If you are interested in learning more about training defecation patterns and pelvic muscle rehabilitation for bowel dysfunction, check out Pelvic Floor Level 2A (PF2A) which discusses in detail fecal incontinence, constipation, and other colorectal conditions. The next opportunity to take this course is in Wisconsin in March. If you have already taken PF2A, you might find a course focused on Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction & the Pelvic Floor, with the next course taking place in Kansas City in April.

Researchers in Brazil assessed the effects of low-frequency and high-frequency TENS, or transcutaneous electrical stimulation on post-episiotomy pain. This randomized, controlled, double-blind trial included the two electrotherapy interventions as well as a control group. TENS was applied for 30 minutes to the three groups: the high-frequency TENS (HFT) (100 Hz, 100 ms) the low-frequency TENS (5 Hz, 100 ms), and the placebo group. Electrode placement was near the episiotomy in a parallel pattern, and pain evaluations were completed before and after TENS application in resting, sitting, and ambulating. (Electrode placement specifics can be found in the article that is available within the above link.) The interventions and pain evaluations were carried out between six and 24 hours after vaginal delivery.

The intensity of the HFT and LFT was controlled by the participants, with instructions to allow the sensation to be both strong and tolerable. A total of 33 participants completed the study, with 11 in the HFT group, 13 in the LFT group, and 9 in the placebo therapy group. The researchers found that for HFT and LFT, pain improved following application of the electrotherapy, and the effects of the pain reduction lasted one hour after the intervention. Because TENS is a low-cost, low-risk modality, TENS use may be a welcome addition for postpartum care following an episiotomy. The women using high or low-frequency TENS in this study reported that TENS was comfortable and that they would opt to use it again.

If you are interested in learning more about postpartum care and issues such as episiotomies which can interfere with return to function, join faculty member Jenni Gabelsberg in Santa Barbara in January. In addition to discussing a wide variety of common musculoskeletal conditions, she will discuss pelvic floor issues following childbirth that can impact a woman's postpartum recovery. Click here to view the learning objectives for Care of the Postpartum Patient as well as additional dates and locations for this course.

This post was written by H&W instructor Michelle Lyons, PT, MISCP, who authored and instructs the course, Special Topics in Women’s Health: Endometriosis, Infertility & Hysterectomy. She will be presenting this course this February!

Endometriosis is a common gynaecological disorder, affecting up to 15% of women of reproductive age. Because endometriosis can only be diagnosed surgically, and also because some women with the disease experience relatively minor discomfort or symptoms, there is some controversy regarding the estimates of prevalence, with some authorities stating that as many as one and three women may have endometriosis (Eskenazi & Warner 1997)

There is a wide spectrum of symptoms of endometriosis, with little or no correlation between the acuteness of the disease and the severity of the symptoms (Oliver & Overton 2014). The most commonly reported symptoms are severe dysmenorrhoea and pelvic pain between periods. Dyspareunia, dyschezia and dysuria are also commonly seen. These pain symptoms can be severe and have been reported to lead to work absences by 82% of women, with an estimated cost in Europe of €30 billion per year (EST 2005). Secondary musculoskeletal impairments caused by may include: lumbar, sacroiliac, abdominal and pelvic floor pain, muscle spasms/ myofascial trigger points, connective tissue dysfunction, urinary urgency, scar tissue adhesion and sexual dysfunction (Troyer 2007) – all of which may be responsive to skilled pelvic rehab intervention.

Endometriosis can lead to inflammation, scar tissue and adhesion formation and myofascial dysfunction throughout the abdominal and pelvic regions. This can set up a painful cycle in the pelvic floor muscles secondary to the decrease in pelvic and abdominal organ/muscle/fascia mobility which can subsequently lead to decreased circulation, tight muscles, myofascial trigger points, connective tissue dysfunction and pain and possible neural irritation.

Abdominal trigger points and pain can be commonly seen after laparascopic surgery for diagnosis or treatment. We know that fascially, the abdominal muscles are closely connected with the pelvic floor muscles and dysfunction in one group may trigger dysfunction in the other, as well as causing associated stability, postural and dynamic stability issues.

The pain created by muscle tension and dysfunction, may lead to further pain and increasing central sensitisation and further disability. Unfortunately for the endometriosis patient, as well as dealing with the problems already associated with endometriosis, she may also develop a spectrum of secondary musculo-skeletal problems, including pelvic floor dysfunction – and for some patients this may actually be responsible for the majority of their pain (Troyer 2007).

The skilled pelvic rehab therapist has much to offer this under-served patient population in terms of reducing pain and dysfunction, educating regarding self-care and exercise and helping to restore quality of life. Interested in learning more? Join me for my new course: ‘Special Topics in Women’s Health: Endometriosis, Infertility & Hysterectomy’ in San Diego this February or Chicago in June.

Pelvic Floor Muscles: To Strengthen or Not to Strengthen?

If that is the question, then who should provide the answer? As I was reading yet another article about how women should strengthen the pelvic floor muscles to have a better orgasm, I can't help but think about the unfortunate women for whom this is a bad idea. Yes, having healthy awareness of and strength in the pelvic floor muscles is important for healthy sexual function, but healthy muscles and building of awareness is challenging to achieve from viewing a few images.

If you clicked on the link above about the article in question, you will see that the recommendation is for activating the pelvic floor muscles and engaging in pelvic strengthening exercises for up to a couple minutes per exercise, with several exercises prescribed up to 2x/day for a period of weeks. And that if you visualize stopping the flow of urine, you will surely feel the muscles activate. Based on clinical experience, we know that this is not the case for most women. One verbal cue may not be enough. The woman may not feel the muscle activation. She may have tight, painful pelvic muscles that are limiting healthy sexual function. These are issues that pelvic rehab providers face on a daily basis: when and how to strengthen the muscles.

Rhonda Kotarinos and Mary Pat Fitzgerald did the world of pelvic rehab an immense good with their promotion of the concept of the "short pelvic floor." If a patient presents with pelvic muscle tension, shortening of the muscle, and poor ability to generate a contraction, a relaxation phase, or a bearing down of the pelvic muscles, how in the world will trying to tighten those overactive muscles bring progress? This concept is further described in a 2012 article from the Mayo Clinic by Dr. Faubion and colleagues. The article explains the cluster of symptoms commonly seen with non-relaxing pelvic floor muscles including pain and dysfunction in bowel, bladder, and sexual function. Medical providers and rehab clinicians should look for this cluster of symptoms and combine this knowledge with a pelvic muscle assessment to decide if pelvic muscle strengthening is warranted.

If this has not been a part of your current practice, please consider ruling out a shortened or non-relaxing pelvic floor prior to suggesting any "Kegels" or pelvic muscle strengthening. If you are well aware of this issue, then it is our responsibility and opportunity to educate the public and the medical community to STOP! strengthening when it is not appropriate. The way I often explain this to patients or students is to pretend that a patient has walked in to the clinic with the shoulders elevated maximally, complaining of headaches or shoulder dysfunction. Then I say, "Great! Let's hit the weights- you just need to strengthen your upper traps." This always gets a giggle or a smirk, but the point is this: that is exactly what providers are doing to patients who walk in with bowel, bladder, pain, or sexual dysfunction when the announcement is made that "you just need to do your Kegels."

While we do not want to villainize Kegels or strengthening of the pelvic muscles, we do want our colleagues, our patients, and the valued referring providers to know that there is way more to pelvic health than strengthening. The abundance of bad advice available to our patients may leave them in worse condition and with less hope about finding relief. While well-intentioned, advice that only describes strengthening as the cure is misleading and potentially harmful.