Most people are told that inguinal hernia repair is a low risk surgery. While death or severe injury is rare, penile or testes pain after hernia repair is not a novel or recent finding. In 1943, Magee first discussed patients having genitofemoral neuralgia after appendix surgery. By 1945, both Magee and Lyons stated that surgical neurolysis gave relief of genital pain following surgical injury (neurolysis is a surgical cutting of the nerve to stop all function). However, it should be noted that with neurolysis, sensory loss will also occur, which is an undesired symptom for sexual function and pleasure. In 1978 Sunderland stated genitofemoral neuralgia was a well-documented chronic condition after inguinal hernia repair.

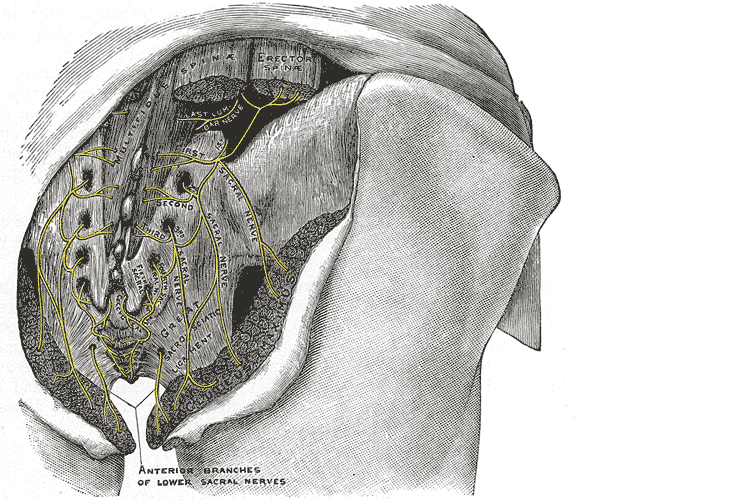

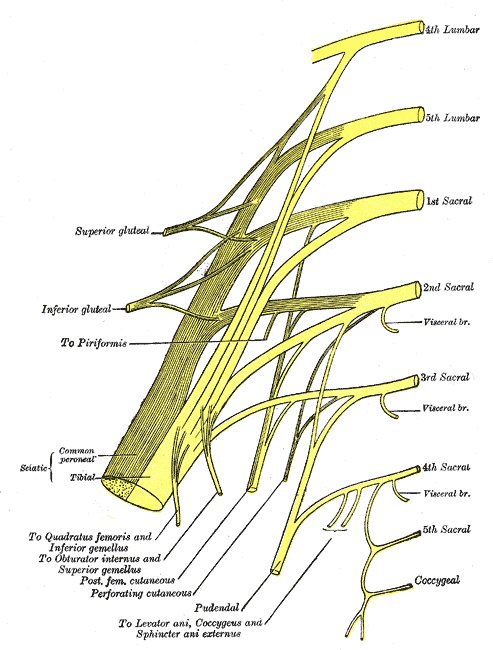

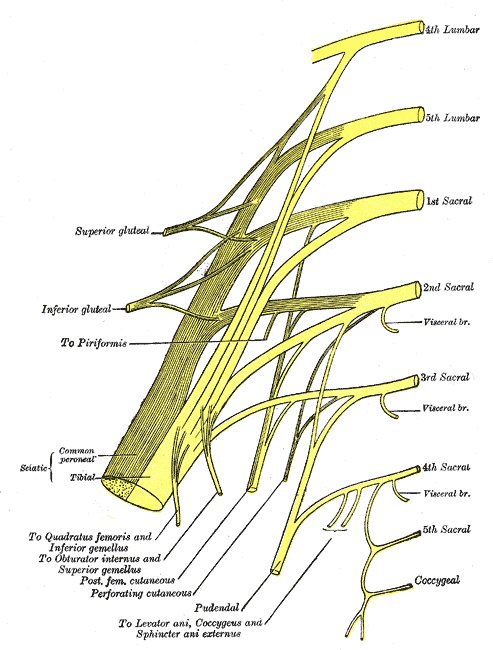

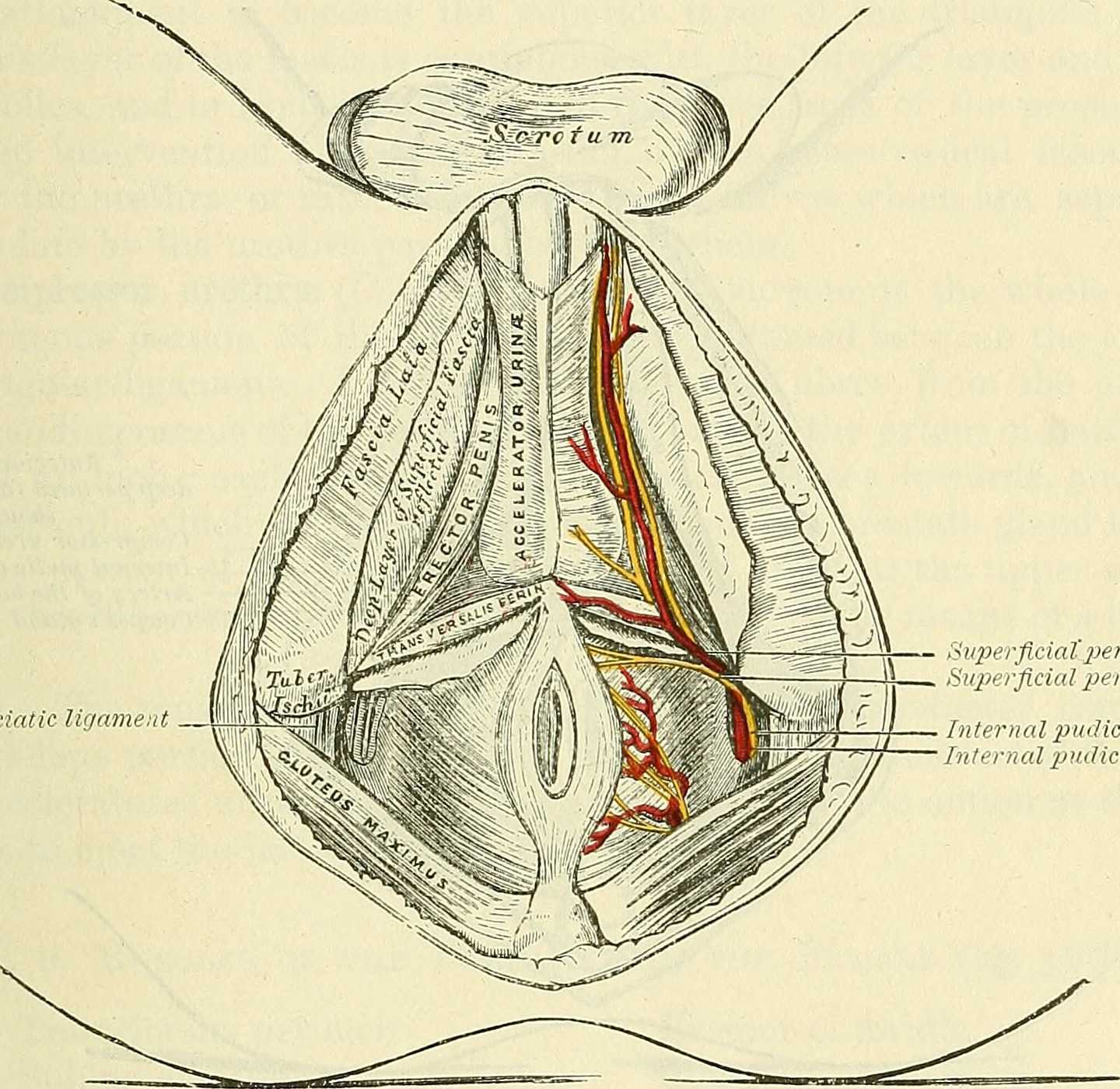

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

In 1999 Stark et al noted pain reports as high as 63% post hernia repair. The highest rates of genitofemoral neuralgia are reported with laparoscopic or open hernia repair (Pencina, 2001). The mechanism for GF neural entrapment is entrapment within scar or fibrous adhesions and parasthesia along the genitofemoral nerve (Harms 1984, Starling and Harms 1989, Murovic 2005, and Ducic 2008). It is well known that scar and adhesion densify and visceral adhesions increase for years after surgery. Thus, symptoms can increase long after the surgery or may take years to develop. In 2006, Brara postulated that mesh in the region can contribute to subsequent genitofemoral nerve tethering which can be exacerbated by mesh in the inguinal or the retroperitoneal space. With an anterior mesh placement, there is no fascial protection left for the genitofemoral nerve.

Genitofemoral neuralgia is predominately reported as a result of iatrogenic nerve damage during surgery or trauma to the inguinal and femoral regions (Murovic et al, 2005). However, genitofemoral neuropathy can be difficulty and elusive to diagnose due to overlap with other inguinal nerves (Harms, 1984 and Chen 2011).

In my clinical experience, I have seen such symptoms after hernia repair, but also after procedures near the inguinal region such as femoral catheters for heart procedures, appendectomies, and occasionally after vasectomy.

As a pelvic PT, what are we to do with this information? First off, we can realize that all pelvic neuropathy is not necessarily due to the pudendal nerve. In the anterior pelvis, there is dual innervation from the inguinal nerves off the lumbar plexus as well as the dorsal branch of the pudendal nerve. When patients have a history of inguinal hernia repair, we can consider the genitofemoral nerve as a source of pain. Medicinally, the only research validated options for treatment are meds such as Lyrica or Gabapentin that come with drowsiness, dizziness and a score of side effects. Surgically neurectomy or neural ablation are options with numbness resulting, however, many patients do not want repeated surgery or numbness of the genitals. As pelvic therapists, we can manually fascially clear the path of the nerve from L1/L2, through the psoas, into and out of the canal and into the genitals. We can also manually directly mobilize the nerve at key points of contact as well as doing pain free sliders and gliders and then give the patient a home program to maintain mobility. Pelvic manual therapy can offer a low risk, side-effect free option to ameliorate the sequella of inguinal hernia repair. Come join us at Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment in Chicago this Spring to learn how to effectively treat all the nerves of the lumbar plexus.

Cesmebasi, A., Yadav, A., Gielecki, J., Tubbs, R. S., & Loukas, M. (2015). Genitofemoral neuralgia: a review. Clinical Anatomy, 28(1), 128-135.

Lyon, E. K. (1945). Genitofemoral causalgia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 53(3), 213.

Magee, R. K. (1943). Genitofemoral Causalgia: New Syndrome. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 98(3), 311.

Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1978

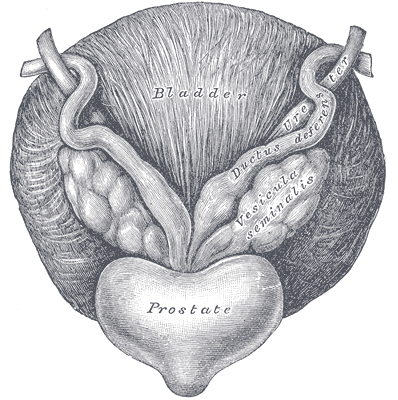

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a debilitation complication of radical prostatectomy, which is a treatment for prostate cancer. ED is caused by a variety of causes, diabetic vasculopathy, smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, psychological issues, peripheral vascular disease and medication; we will focus on post-prostatectomy ED and the role of penile rehabilitation in its management.

Post-prostatectomy-related Erectile dysfunction

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Research on penile hemodynamics in these patients have shown that venous leakage is also implicated in its pathophysiology. An injury to the neurovascular bundles likely leads to smooth muscle cell death, which then leads to irreversible veno-occlusive disease.

There is a potential role of hypoxia in stimulating growth factors (TGF-beta) that stimulate collagen synthesis in cavernosal smooth muscle. Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) was found to suppress the effect of TGF-β1 on collagen synthesis.

Role of Penile Rehabilitation

The goal of Penile Rehabilitation is to limit and reverse ED in post-prostatectomy patients. The idea is to minimize fibrotic changes during the period of “penile quiescence” after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Several approaches have been tried, including PGE1 injection, vacuum devices, and phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) inhibitors.

Mulhall and coworkers followed 132 patients through an 18-month period after they were placed in “rehabilitation” or “no rehabilitation” groups after radical prostatectomy, and 52% of those undergoing rehabilitation (sildenafil + alprostadil) reported spontaneous functional erections, compared with 19% of the men in the no-rehabilitation group 2.

Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1)

Alprostadil is a vasodilatory prostaglandin E1 that can be injected into the penis or placement in the urethra in order to treat ED. Montorsi, et al. studied the use of intracorporeal injections of alprostadil starting at 1 month after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and reported a higher rate of spontaneous erections after 6 months compared with no treatment 3. Gontero, et al. investigated alprostadil injections at various time points after non–nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and found that 70% of patients receiving injections within the first 3 months were able to achieve erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 40% of patients receiving injections after the first 3 months 4.

Vacuum constriction device (VCD)

VCD is an external pump that is used to get and maintain an erection. Raina, et al evaluated the daily use of a VCD beginning within two months after radical prostatectomy, and reported that after 9 months of treatment, 17% of patients using the device had return of natural erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 11% of patients in the nontreatment group 4.

PDE-5 Inhibitors

PDE-5 inhibitors (such as Sildenafil) are the first-line treatment for ED of many etiologies. Several studies have shown that the use of PDE-5 inhibitors might lead to an overall improvement in endothelial cell function in the corpus cavernosum. Chronic use of oral PDE-5 inhibitors suggest a beneficial effect on endothelial cell function. Desouza, et al. concluded that daily sildenafil improves overall vascular endothelial cell function. However, Zagaja, et al. found that men taking oral sildenafil within the first 9 months of a nerve-sparing procedure did not have any erectogenic response 4.

Overall, accumulating scientific literature is suggesting that penile rehabilitation therapies have a positive impact on the sexual function outcome in post-prostatectomy patients. It must be noted that these methods do not cure ED and should be used with caution.

1Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701-1705.

2Mulhall J, Land S, Parker M, et al. The use of an erectogenic pharmacotherapy regimen following radical prostatectomy improves recovery of spontaneous erectile function. J Sex Med. 2005; 2:532-540.

3Montorsi F, Guazzoni G, Strambi LF, et al. Recovery of spontaneous erectile function after nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy with and without early intracavernous injections of alprostadil: results of a prospective, randomised trial. J Urol. 1997;158:1408-1410.

4Gontero P, Fontana F, Bagnasacco A, et al. Is there an optimal time for intracavernous prostaglandin E1 rehabilitation following non- nerve sparing radical prostatectomy? Results from a hemodynamic prospective study. J Urol. 2003;169:2166-2169.

Managing a medical crisis such as a cancer diagnosis can be overwhelming for an individual. Faced with choices about medical options, dealing with disruptions in work, home and family life often leaves little energy left to consider sexual health and intimacy. Maintaining closeness, however, is often a goal within a partnership and can aid in sustaining a relationship through such a crisis. The research is clear about cancer treatment being disruptive to sexual health, yet intimacy is a larger concept that may be fostered even when sexual activity is impaired or interrupted. Last year, when I was asked to speak to the Pacific NW Prostate Cancer Conference about intimacy, I was pleasantly surprised to find a rich body of literature about maintaining intimacy despite a diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

If the patient brings up sexual health, or we encourage the conversation, there are many research-based suggestions we can provide to encourage recovery of intimacy, several are listed below.

- Manage general health, fitness, nutrition, sleep, anxiety and stress

- Redefine sex as being beyond penetration, consider other sexual practices such as massage/touch, cuddling, talking, use of vibrators, medication, aids such as pumps (Usher et al., 2013)

- Participate in couples therapy to understand partners’ needs, address loss, be educated about sexual function (Wittman et al., 2014; Wittman et al., 2015)

- Participate in “sensate focus” activities (developed by Masters & Johnson in 1970’s as “touch opportunities”) with appropriate guidance (Weiner & Avery-Clark 2017)

Within the context of this information, there is opportunity to refer the patient to a provider who specializes in sexual health and function. While some rehabilitation professionals are taking additional training to be able to provide a level of sexual health education and counseling, most pelvic health providers do not have the breadth and depth of training required to provide counseling techniques related to sexual health- we can, however, get the conversation started, which in the end may be most important.

In the men’s health course, we further discuss sexual anatomy and physiology, prostate issues, and look at the research describing models of intimacy and what worked for couples who did learn to renegotiate intimacy after prostate cancer.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2009, April). Sexual intimacy in heterosexual couples after prostate cancer treatment: What we know and what we still need to learn. In Urologic oncology: seminars and original investigations (Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 137-143). Elsevier.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2013). Sexual Values as the Key to Maintaining Satisfying Sex After Prostate Cancer Treatment : The Physical Pleasure–Relational Intimacy Model of Sexual Motivation. Archives of sexual behavior, 42(8), 1637-1647.

Gilbert, E., Ussher, J. M., & Perz, J. (2010). Renegotiating sexuality and intimacy in the context of cancer: the experiences of carers. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(4), 998-1009.

Hawkins, Y., Ussher, J., Gilbert, E., Perz, J., Sandoval, M., & Sundquist, K. (2009). Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: the experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer nursing, 32(4), 271-280.

Higano, C. S. (2012). Sexuality and intimacy after definitive treatment and subsequent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(30), 3720-3725.

Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., Gilbert, E., Wong, W. T., & Hobbs, K. (2013). Renegotiating sex and intimacy after cancer: resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nursing, 36(6), 454-462.

Weiner, L., Avery-Clark, C. (2017). Sensate Focus in Sex Therapy: The Illustrated Manual. Routledge, New York.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., An, L., Palapattu, G., & Montie, J. E. (2014). Exploring the role of the partner in couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(9), 2509-2515.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., Crossley, H., An, L., ... & Montie, J. E. (2015). What couples say about their recovery of sexual intimacy after prostatectomy: toward the development of a conceptual model of couples' sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. The journal of sexual medicine, 12(2), 494-504.

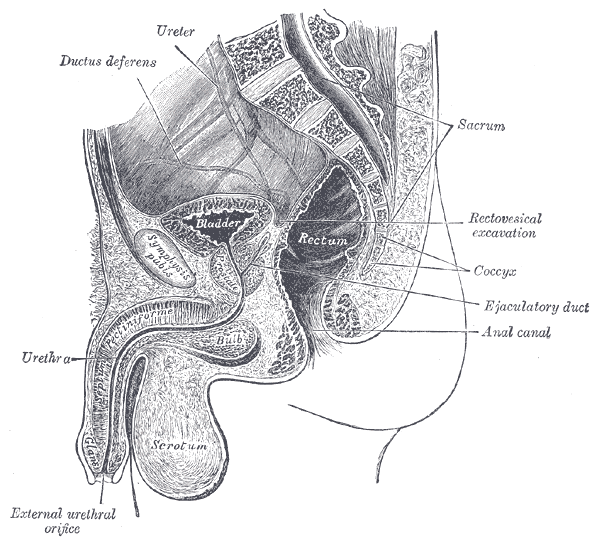

Men who present with chronic pelvic pain frequently have symptoms referred along the penis and into the tip of the penis, or glans. Symptoms may include numbness, tingling, aching, pain, or other sensitivity and discomfort. The tip of the penis, or glans, is a sensory structure, which allows for sexual stimulation and appreciation. This same capacity for valuable sensation can create severe discomfort when signals related to the glans are overactive or irritating. One of the most common complaints with this symptom is a level of annoyance and distraction, with level of bother worsening when a person is less active or not as mentally engaged with tasks. Wearing clothing that touches the tip of the penis (such as underwear, jock straps, jeans, or snug pants) may be limited and may worsen symptoms. When uncovering from where the symptoms originate, the culprit is often the dorsal nerve of the penis, which is sensible given that the glans is innervated by this branch of the pudendal nerve. If we consider this possibility (because certainly there are other potential causes) we find that there are many potential sites of pudendal nerve irritation to consider. First, let’s visualize the anatomy of the nerve.

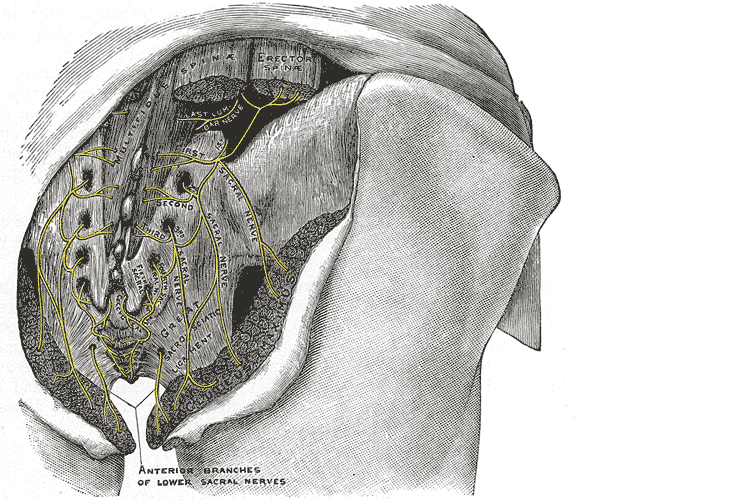

Following the usually accepted descriptions of the dorsal nerve, we know that it is a terminal branch of the pudendal nerve that primarily is created from the mid-sacral nerves. This can lead us to include the lumbosacral region in our examination and treatment, yet in my clinical experience, there are other sites that more often reproduce pain in the glans. As the dorsal nerve branches off of the pudendal, usually after the location of the sacrotuberous ligament, it passes through and among the urogenital triangle layers of fascia where compression or irritation may generate symptoms.

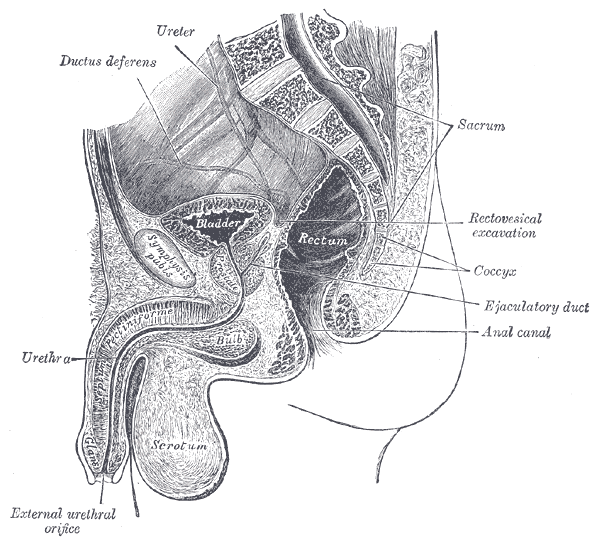

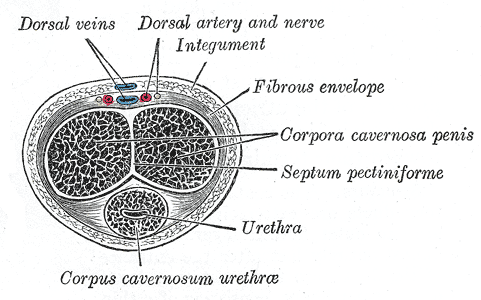

As the nerve travels towards the pubic bone, it will pass inferior to the pubic bone, a location where suspensory ligaments of the penis can be found as well as pudendal vessels and fascia. This is also a site of potential compression and irritation, and palpation to this region may provide information about tissue health. Below is a cross-section of the proximal penis, allowing us to see where the pudendal nerve and vessels would travel inferior to the pubic bone.

As the dorsal nerve extends along either side of the penis, giving smaller branches along its path towards the glans, the nerve may also be experiencing soft tissue irritation along the length of the penis or even locally at the termination in the glans.

Palpation internally (via rectum) or externally may be a part of the assessment as well as treatment of this condition. Oftentimes, tip of the penis pain can be reproduced with palpation internally and directed towards the anterior levator ani and the connective tissues just inferior to the pubic bone. It may be difficult to know if the muscle is providing referred pain, or if the nerve is being tensioned and reproducing symptoms, however gentle soft tissue work applied to this area is often successful in reducing or resolving symptoms regardless of the tissue involved. In my experience, these symptoms of referred pain at the tip of the penis is often one of the last to resolve, and the use of topical lidocaine may be helpful in managing symptoms while healing takes place. Home program self-care including scar massage if needed, nerve mobilizations, trunk and pelvic mobility and strengthening, and advice for returning to meaningful activities can play a large role in resolution of pain in the glans.

If you would like to learn more about treating genital pain in men, consider joining me in Male Pelvic Floor: Function, Dysfunction, & Treatment. The 2018 courses will be in Freehold, NJ this June, and Houston, TX in September.

In 2007, after only speaking on the phone and never meeting in person, my new friend and colleague Stacey Futterman and I presented at the APTA National Conference on the topic of male pelvic pain. It was a 3 hour lecture that Stacey had been asked to give, and she invited me to assist her upon recommendation of one of her dear friends who had heard me lecture. I still recall the frequent glances I made to match the person behind the voice I had heard for so many long phone calls.

Upon recommendation of Holly Herman, we took this presentation and developed it into a 2 day continuing education course, creating lectures in male anatomy (we definitely did not learn about the epididymis in my graduate training), post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence, pelvic pain, and a bit about sexual health and dysfunction. Although it truly seems like the worst imaginable question, we asked each other “should we allow men to attend?” As strange as this question now seems, it speaks volumes about the world of pelvic health at that time; mostly female instructors taught mostly female participants about mostly female conditions.

Upon recommendation of Holly Herman, we took this presentation and developed it into a 2 day continuing education course, creating lectures in male anatomy (we definitely did not learn about the epididymis in my graduate training), post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence, pelvic pain, and a bit about sexual health and dysfunction. Although it truly seems like the worst imaginable question, we asked each other “should we allow men to attend?” As strange as this question now seems, it speaks volumes about the world of pelvic health at that time; mostly female instructors taught mostly female participants about mostly female conditions.

Make no mistake- women’s health topics were and are deserving of much attention in our typically male-centered world of medicine and research. Maternal health in the US is dreadful, and gone are the days when providers should allow urinary incontinence or painful sexual health to be “normal”, yet it is often described as such to women who are brave enough to ask for help. Times have changed for the better for us all.

The Male Pelvic Floor Course was first taught in 2008, and so far, 22 events have taken place in 18 different cities. 73 men have attended the course to date, with increasing numbers represented at each course. Rather than 20-25 attendees, the Institute is seeing more of the men’s health course filling up with 35-40 participants. In my observations, the men who attend the course are often very experienced, have excellent orthopedic and manual therapy skills, and have personalities that fit very well into the sensitive work that is pelvic rehabilitation.

The course was expanded to include 3 days of lectures and labs, and this expansion allowed more time for hands-on skills in examination and treatment. The schedule still covers bladder, prostate, sexual health and pelvic pain, and further discusses special topics like post-vasectomy syndrome, circumcision, and Peyronie’s disease. In my own clinical practice, learning to address penile injuries has allowed me to provide healing for conditions that are yet to appear in our journals and textbooks. As I often say in the course, we are creating male pelvic rehabilitation in real time.

Because the course often has providers in attendance who have not completed prior pelvic health training, instruction in basic techniques are included. For the experienced therapists, there are multiple lab “tracks” that offer intermediate to advanced skills that can be practiced in addition to the basic skills. Adaptations and models are used when needed to allow for draping, palpation, and education when working with partners in lab, and space is created for those therapists who want to learn genital palpation more thoroughly versus those who are deciding where their comfort zone is at the time. One of the more valuable conversations that we have in the course is how to create comfort and ease in when for most us, we were raised in a culture (and medical training) where palpation of the pelvis was not made comfortable. Hearing from the male participants about their bodies, how they are affected by cultural expectations, adds significant value as well.

We need to continue to create more coursework, more clinical training opportunities so that the representation of those treating male patients improves. If you feel ready to take your training to the next level in caring for male pelvic dysfunction, this year there are three opportunities to study. I hope you will join me in Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction and Treatment.

Today we pick up on Jennafer Vande Vegte's interview with her patient, "Ben", about his experience overcoming chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Ben's quality of life improved so much that he has returned to school in order to become a PTA, with a focus on pelvic rehabilitation!

Describe your physical therapy experience. Talk about your recovery process. Include the physical, mental and emotional components.

For my initial visit, my therapist questioned and assessed my pain, then explained pelvic floor dysfunction. She made sure I understood that the evaluation and treatment process involved internal rectal work. After developing the condition and months of seeing doctors who didn’t listen, finally I found a physical therapist who was actually listening to me and determined to get to the bottom of what was going on. I could tell she already knew much about the mechanics (if not the exact cause) because she had treated other patients with the same issues. I immediately sensed a difference from any other health care professional in attitude, compassion, and knowledge. Of course, how do you know for sure? Well, you don’t. But after repeated visits and excellent results, you experience the difference. An important realization while going to Physical Therapy is learning to see the mind-body connection. In the back of my mind I sensed that my pain was being perpetuated by emotional trauma. This is not an intuitive way of thinking when you are in constant high-level, 5-alarm pain. I was obsessed with finding the cause of my pain, but chronic pain is extremely elusive and complicated.

For my initial visit, my therapist questioned and assessed my pain, then explained pelvic floor dysfunction. She made sure I understood that the evaluation and treatment process involved internal rectal work. After developing the condition and months of seeing doctors who didn’t listen, finally I found a physical therapist who was actually listening to me and determined to get to the bottom of what was going on. I could tell she already knew much about the mechanics (if not the exact cause) because she had treated other patients with the same issues. I immediately sensed a difference from any other health care professional in attitude, compassion, and knowledge. Of course, how do you know for sure? Well, you don’t. But after repeated visits and excellent results, you experience the difference. An important realization while going to Physical Therapy is learning to see the mind-body connection. In the back of my mind I sensed that my pain was being perpetuated by emotional trauma. This is not an intuitive way of thinking when you are in constant high-level, 5-alarm pain. I was obsessed with finding the cause of my pain, but chronic pain is extremely elusive and complicated.

Over the course of many months of PT though we couldn’t pinpoint what started the pain, we knew my nervous system was keeping it going. Sensory signals had somehow been rerouted through pain centers in the delicate and complicated highway interstate of the nervous system. It was as if the Fed Ex truck that was supposed to carry a package from Miami to Denver got rerouted to New York, stuck in traffic in Manhattan, flipped off by cab drivers, beaten up by gang members, contents of the truck shaken up by the driver trying to flee the city, and then finally finding the way out of New York to the true destination of Denver – with damaged goods, and shaking with anxiety. As to who the idiot dispatcher was who re-routed the truck to New York, well, he’s really good at keeping himself secret and innocent-looking. Jerk!

Physical therapy, over time, began to work for me. It released trigger points which are the first step in the long process of recovery. As we know, chronic tension must be addressed in tissues and nerves, and the mind must relearn how to remain in neutral. I found that as I gained periods of relief I could see that there truly was a mind-body connection beyond what I could imagine. My physical therapist and I both knew that nerves are the slowest recovering tissue in the body, and when you combine that with an anxious mind, you have a complicated puzzle to solve. There is definitely a closed circuit that develops with chronic pelvic pain. Pain causes anxiety, anxiety causes pain and circularly they feed one another.

During my physical therapy I joined a male pelvic pain message board online. I began understanding that most men who develop pelvic pain also have experienced traumatic emotional stress. And a large part of chronic pelvic pain is rooted in a mind-body dysfunction. I had to learn how to stop thinking catastrophically, especially during flare ups. I had to trust that my body would heal and think positively. I had to learn how to relax, take care of myself, eat well, stretch and exercise daily.

When I started physical therapy, I hoped to escape the pain. My first 5 month phase of physical therapy helped to loosen the chronically tightened pelvic sphincter muscles. However, I still had allodynia. In my second phase of physical therapy I began experiencing reduction of pain for a longer duration of time. After about a year of therapy, I finally got to a point where I could see there was significant improvement, even though some intermittent pain and anxious symptoms stubbornly persisted. In late spring of 2017, I finally felt like I had conquered the pain by 98%. Occasionally flares would still come, but they were brief and nothing like before physical therapy.

How has your experience with chronic pelvic pain changed you?

CPPS has profoundly changed me. I don’t take the little things for granted or sweat them anymore. I am grateful for not feeling that horrible, hellish sensation any longer. I appreciate having my mind pain and panic free. I speak my mind while respecting my own desires instead of belittling them. I am currently in school to become a Physical Therapy Assistant as through this process I learned that I’m actually much smarter than my middle school guidance counselor thought. I understand the mind is incredibly powerful, and fear rarely has the same power over me.

How do you handle flare ups?

I now handle brief flare ups with deep breaths, meditation, and/or just taking a step back and trying to zero in on what is really bothering me. At least now I can clearly think without debilitating pain and am able to function.

What would you like to say to other people who are struggling with chronic pelvic pain?

Oh, man. For the initial duration, I would say find a safe place where you can feel as comfortable as possible until the pain lessens. When it is bad, you sort of have to give in to it. However, part of this recovery is the physical mechanics of muscle and fascia. Physical Therapy is essential in the process of recovery to release this tension. I would tell them not to give up hope. You will not find many health professionals or websites that will tell you that you can beat this and recover 100%. But I will tell you, you can recover, 100%. You can. But for now, your full-time job is to work on recovery, and that includes lots of self-care, facing possible emotional pain, and physical therapy.

If you would like to learn more about addressing the mind body connection with patients please join us for Holistic Intervention and Meditation: Boundaries, Self-Care and Dialog in January. We will be exploring ways to help our patients heal to their fullest potential as well as keeping ourselves emotionally healthy in the process. Treating patients with persistent pain can be challenging for the best of us. Please come for this three-day course where you will leave feeling refreshed, renewed and reinvigorated to treat even your most complex patient.

Additional resources:

https://www.tamethebeast.org/#home

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jIsF8CXouk8

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1356689X11000737

http://www.noigroup.com/en/Home

https://bodyinmind.org/who-are-we/

Recently my coworkers and I celebrated a male patient’s recovery from a long and difficult journey with persistent pelvic pain. “Ben’s” case had many elements of what we normally see in our patients: chronic muscle holding, restricted fascia, allodynia, hyperalgesia, castrophizing and kenisiophobia. Ben was also very upfront about how his pain impacted his emotional well-being and vice versa. His healing process taught us a lot about the biopsychosocial aspects of treating persistent pain. Along his journey we dreamed of the day we could write a blog together and help other people learn from the experience. Ben also decided to make a career change entering school to become a PTA so that he could help others in pain. Here is my interview with this brave patient.

1. Tell us about how your pain started

1. Tell us about how your pain started

My pain started with urethral burning. Tests showed there was no infection. In retrospect, the cause of pain could have been the beginning of tension on pudendal nerve branches from extreme stress and a series of traumatic incidents that happened within weeks of each other. They included a very embarrassing and stressful summer of unemployment, a father who had heart failure and triple bypass in the fall, and a girlfriend who gave me an ultimatum when I was too stressed to get an erection.

2. What medical tests or treatments were done?

When the pain started, I first thought it was a basic urinary tract infection. I went to the med center and was prescribed an antibiotic. After 3 days without change, I went back in and although they still found no sign of infection, they prescribed an additional antibiotic. The urethral pain never stopped and seemed to get worse. Following a series of visits to numerous doctors and urologists, I repeated tests on the prostate fluid, blood tests, and more bacterial tests. No infection. My PCP also made a fairly large overture of testing me repeatedly for HIV. For five months I had a blood test every month, all came back negative. This was damaging to my psyche. For those months I was terrified my life was over. In retrospect, that doctor was out of line, I changed doctors.

3. What were your thoughts when your doctor suggested physical therapy?

When the doctor suggested pelvic floor physical therapy, I was a little skeptical because I was still convinced that something was wrong in a chemical or infectious way (as is typical for most men with pelvic floor dysfunction). However, desperate to take away the constant pain, I followed the advice.

Stay tuned for part two of our conversation with Ben, coming up in our next post on the Pelvic Rehab Report!

As I read about male phimosis, I thought about a shirt that just won’t go over my son’s big noggin. I tug and pull, and he screams as his blond locks stick up from static electricity. Ultimately, if I want this shirt to be worn, I either have to cut it or provide a prolonged stretch to the material, or my child will suffocate in a polyester sheath. This is remotely similar to the male with physiological phimosis.

In a review article, Chan and Wong (2016) described urological problems among children, including phimosis. They reported “physiological phimosis” is when the prepuce cannot be retracted because of a natural adhesion to the glans. Almost all normal male babies are born with a foreskin that does not retract, and it becomes retractable in 90% of boys once they are 3 years old. A biological process occurs, and the prepuce becomes retractable. In “pathological phimosis” or balanitis xerotica obliterans, the prepuce, glans, and sometimes even the urethra experience a progressive inflammatory condition involving inflammation of the glans penis, an unusually dry lesion, and occasional endarteritis. Etiology is unknown, but males by their 15th birthday report a 0.6% incidence, and the clinical characteristics include a white tip of the foreskin with a ring of hard tissue, white patches covering the glans, sclerotic changes around the meatus, meatal stenosis, and sometimes urethral narrowing and urine retention.

In a review article, Chan and Wong (2016) described urological problems among children, including phimosis. They reported “physiological phimosis” is when the prepuce cannot be retracted because of a natural adhesion to the glans. Almost all normal male babies are born with a foreskin that does not retract, and it becomes retractable in 90% of boys once they are 3 years old. A biological process occurs, and the prepuce becomes retractable. In “pathological phimosis” or balanitis xerotica obliterans, the prepuce, glans, and sometimes even the urethra experience a progressive inflammatory condition involving inflammation of the glans penis, an unusually dry lesion, and occasional endarteritis. Etiology is unknown, but males by their 15th birthday report a 0.6% incidence, and the clinical characteristics include a white tip of the foreskin with a ring of hard tissue, white patches covering the glans, sclerotic changes around the meatus, meatal stenosis, and sometimes urethral narrowing and urine retention.

This review article continues to discuss the appropriate treatment for phimosis (Chan & Wong 2016). Once phimosis is diagnosed, the parents of the young male need to be educated on keeping the prepuce clean. This involves retracting the prepuce gently and rinsing it with warm water daily to prevent infection. Parents are warned against forcibly retracting the prepuce. A study has shown complete resolution of the phimosis occurred in 76% of boys by simply stretching the prepuce daily for 3 months. Topical steroids have also been used effectively, resolving phimosis 68.2% to 95%. Circumcision is a surgical procedure removing foreskin to allow a non-covered glans. Jewish and Muslim boys undergo this procedure routinely, and >50% of US boys get circumcised at birth. Medical indications are penile malignancy, traumatic foreskin injury, recurrent attacks of severe balanoposthitis (inflammation of the glans and foreskin), and recurrent urinary tract infections.

Pedersini et al., (2017) evaluated the functional and cosmetic outcomes of “trident” preputial plasty using a modified-triple incision for surgically managing phimosis in children ages 3-15. All patients seen in a 1 year period who were unable to retract the foreskin and had posthitis or balanoposthitis or ballooning of the foreskin during urination were included and treated initially with a two-month trial of topic corticosteroids. Only the patients unresponsive to corticosteroids were treated with the "trident" preputial plasty. At 12 months post-surgery, 97.6% (all but one of the 41 subjects) of patients were able to retract the prepuce, and cosmetics and function were satisfactorily restored.

Phimosis is apparently not a highlight in medical school curriculum, and parents often seek attention for other issues that lead to the diagnosis of phimosis. Like the tight material lining the neck of a shirt, the prepuce can be given a prolonged static stretch, and, over time, may retract appropriately. Or, cutting the shirt material may be necessary for long term success. Similarly, surgical intervention such as circumcision or the newer “trident” preputial plasty may be required.

Chan, Ivy HY and Wong, Kenneth KY. (2016). Common urological problems in children: prepuce, phimosis, and buried penis. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 22(3):263–9. DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154645

Pedersini, P, Parolini, F, Bulotta, AL, Alberti, D. (2017). "Trident" preputial plasty for phimosis in childhood. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 13(3):278.e1-278.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.01.024

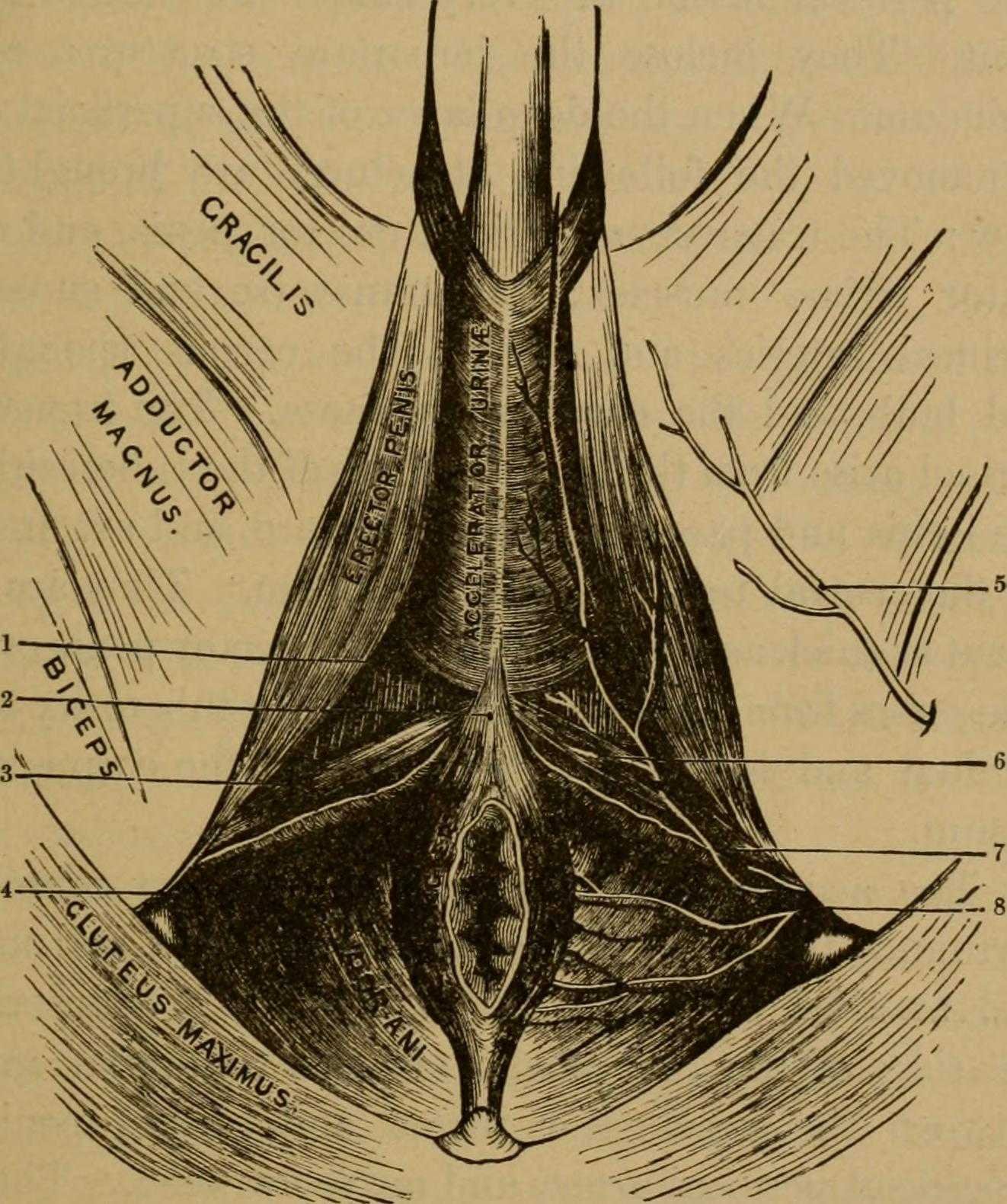

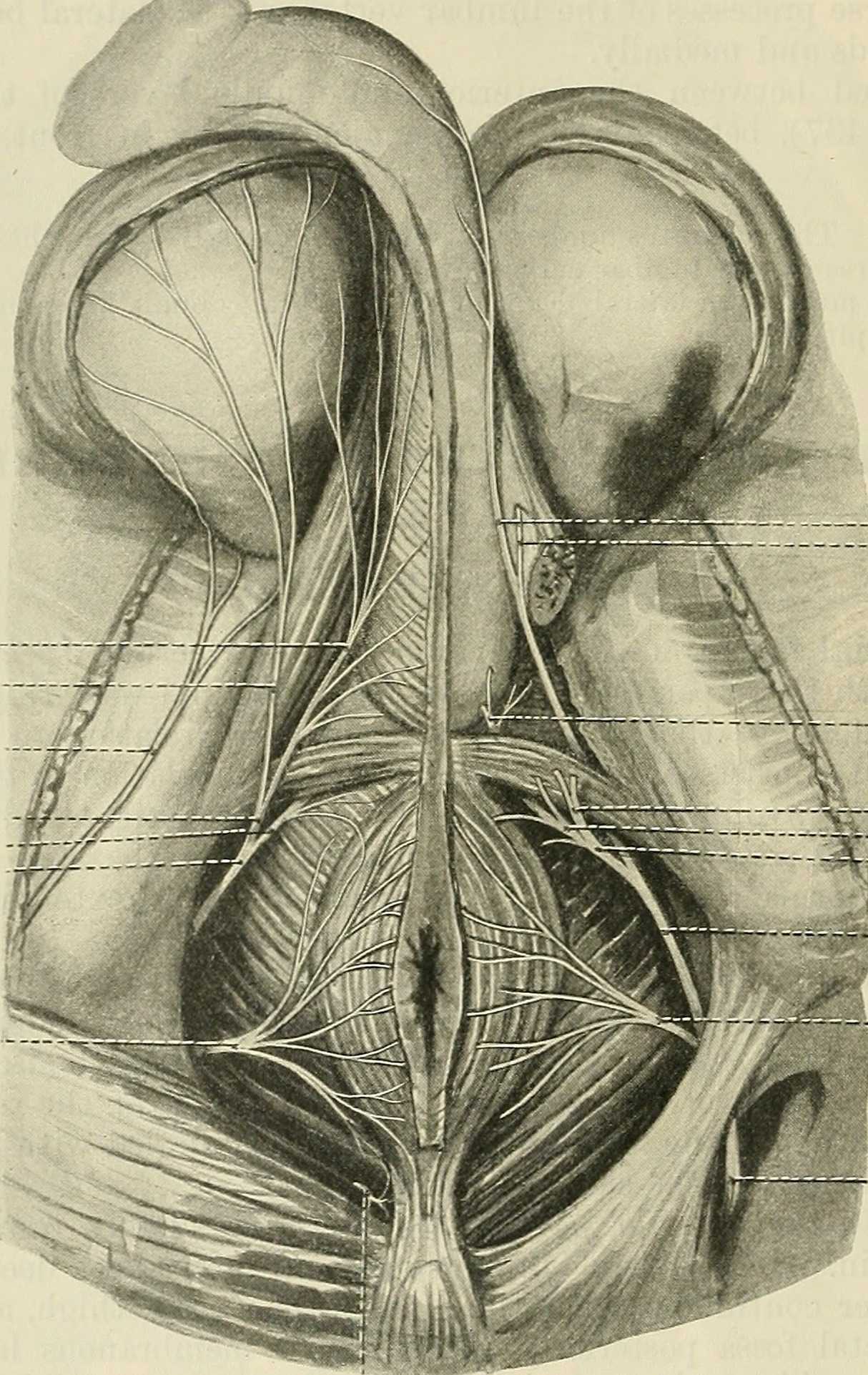

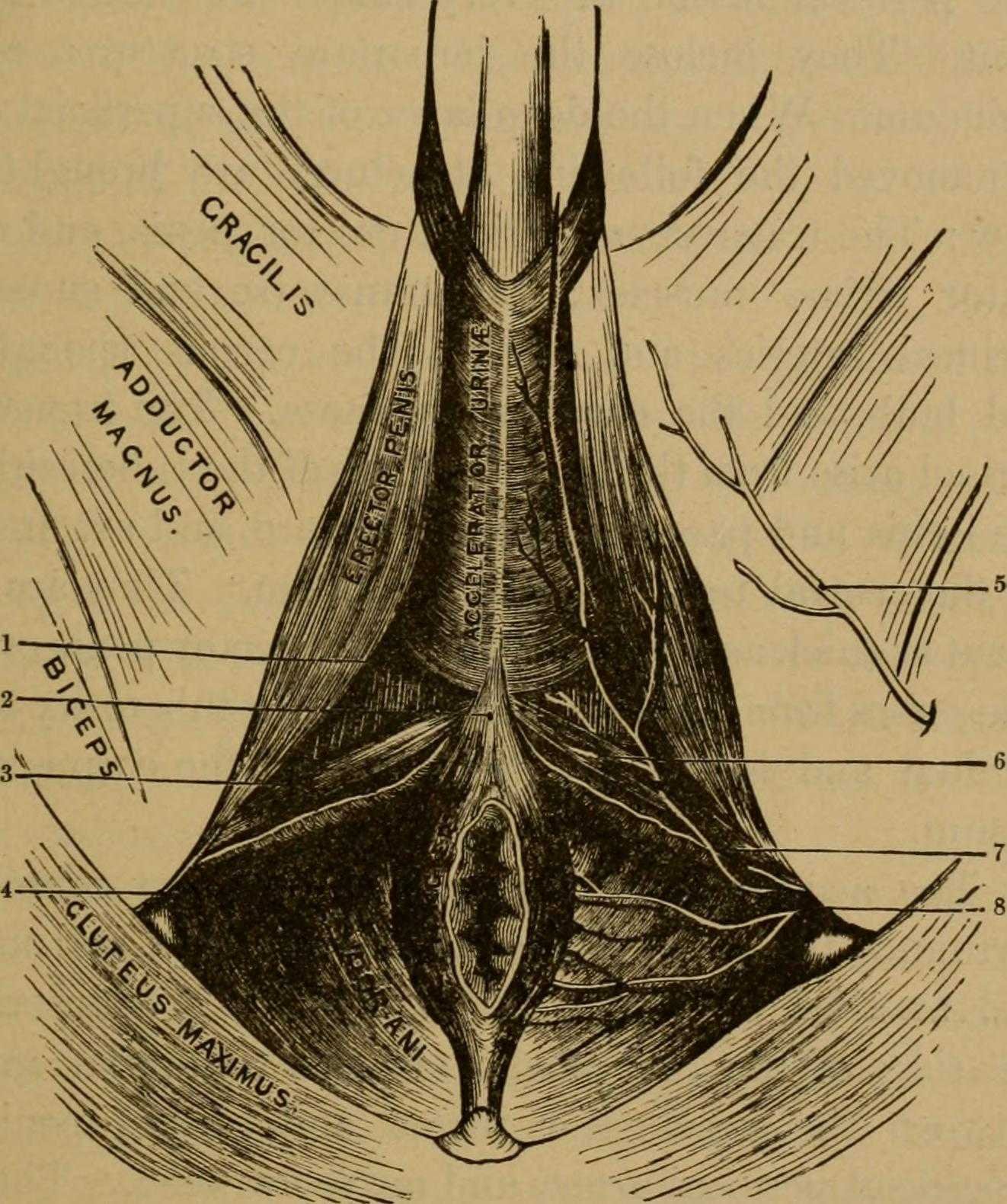

Many therapists transition to treating men with the knowledge and training from female patients. When therapists apply this knowledge, for the most part, it works. When we spend some attention on learning what is a bit different, we might be drawn to the superficial muscles of the perineum. This old anatomy image does a wonderful job of "calling it like it is" or using anatomical terms that describe an action versus naming only the structure. In the image we are looking from below (inferior view) at the perineum and genitals. Just anterior to the anus we can see the anterior muscles within the urogenital triangle, with the base of the shaft of the penis located just anterior to (above in this image) the anus and perineal body. Notice that at the midline, we see muscle names the "accelerator urine". Modern textbooks refer to this muscle as the bulbocavernosus, or bulbospongiosus. Taking the name of accelerator urine, we can understand that this muscle will have an effect on aiding the body in emptying urine. It does this through rhythmic contractions, most often noted towards the end of urination, when the typical spurts of urine follow a more steady stream. This assistance with emptying can take place because the urethra is located within the lower part of the penis, the portion known as the corpus spongiosum. Because the bulbocavernosus muscle covers this part of the penis, and the inferior and lateral parts of the urethra are virtually wrapped within the bulbocavernosus, the muscle can have an effect on emptying the urine in the urethra.

Many therapists transition to treating men with the knowledge and training from female patients. When therapists apply this knowledge, for the most part, it works. When we spend some attention on learning what is a bit different, we might be drawn to the superficial muscles of the perineum. This old anatomy image does a wonderful job of "calling it like it is" or using anatomical terms that describe an action versus naming only the structure. In the image we are looking from below (inferior view) at the perineum and genitals. Just anterior to the anus we can see the anterior muscles within the urogenital triangle, with the base of the shaft of the penis located just anterior to (above in this image) the anus and perineal body. Notice that at the midline, we see muscle names the "accelerator urine". Modern textbooks refer to this muscle as the bulbocavernosus, or bulbospongiosus. Taking the name of accelerator urine, we can understand that this muscle will have an effect on aiding the body in emptying urine. It does this through rhythmic contractions, most often noted towards the end of urination, when the typical spurts of urine follow a more steady stream. This assistance with emptying can take place because the urethra is located within the lower part of the penis, the portion known as the corpus spongiosum. Because the bulbocavernosus muscle covers this part of the penis, and the inferior and lateral parts of the urethra are virtually wrapped within the bulbocavernosus, the muscle can have an effect on emptying the urine in the urethra.

Notice that if you follow the fibers of the accelerator urine muscle towards the top of the image, where the penis continues, you will notice fibers of the muscle wrapping around the sides of the penis. These fibers will continue as a fascial band that travels over the dorsal vessels of the penis. This allows the muscle to also have a significant action during sexual activity, in which blood flow (getting blood into, keeping blood in, and letting blood out of the penis) is paramount.

On either side of the penis we can see what is labeled the erector penis. As these muscles cover the legs, or crura which form the two upper parts of the penis, when the muscles contract, blood is shunted towards the main body of the penis. This of course helps with penile rigidity, as the smooth muscles in the artery walls of the penis allow blood to fill the spongy chambers.

Once we discuss the usual functions of these muscles, we can then imagine the dysfunctions potentially created by less than optimal activity. Consider the difficulty that these muscles will create in contracting or relaxing if they are either too weak, or too tense. These issues can create difficulty emptying well the urethra, often leading to post-void dribble. Blood flow and therefore penile rigidity with erections may be negatively impacted by inability of these muscles to contract or stay contracted, and blood flow leaving the penis may be impaired if the muscles cannot relax. When we work with patients who have genital pain, pelvic floor muscle weakness, dyscoordination, or tension, we can often improve sexual function, bladder emptying, and tasks that might otherwise be affected by pain.

If you are interested in learning more about how to assess and treat these muscles, you have one more opportunity this year to attend the 3-day Male Course instructed by Holly Tanner. Holly has been teaching this course for over 10 years when she co-wrote the first course with colleague and faculty member Stacey Futterman. The course has been updated and turned into a 3-day course to include more manual therapy techniques. Hurry to grab one of the remaining spots in the October 27-29 course in Grand Rapids!

The Center for Disease Control reports that prostate cancer is the most common form of male cancer in the United States (just ahead of lung cancer and colorectal cancer), and the American Cancer Society estimates that 1 in 7 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point in their lifetime. With prostate cancer being so common, it is likely that a male with symptoms of urinary incontinence following a prostatectomy may show up at your clinic’s door for treatment. What do you do? Whether you have extensive training for male pelvic floor disorders or are just starting your initial training for pelvic floor dysfunctions, you likely have some intervention skills to help this population.

A recent case report in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, outlines management of a 76-year-old male patient with mixed urinary incontinence postprostatectomy 10 years. This case report does a nice job describing not just physical therapy (PT) interventions, but also multifaceted management of a typical patient post radical prostatectomy. The case report describes a thorough history, systems review, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) examination, tests &measures, and outcome assessment. Our discussion will focus on interventions as you may already possess the skills for several of the treatments included in this patient’s plan of care.

A recent case report in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, outlines management of a 76-year-old male patient with mixed urinary incontinence postprostatectomy 10 years. This case report does a nice job describing not just physical therapy (PT) interventions, but also multifaceted management of a typical patient post radical prostatectomy. The case report describes a thorough history, systems review, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) examination, tests &measures, and outcome assessment. Our discussion will focus on interventions as you may already possess the skills for several of the treatments included in this patient’s plan of care.

The patient’s complaints were mixed urinary incontinence (UI) symptoms including 3-4 pads per day and 1 pad at night. He reported nocturia 3-4 times per night. 2-3 times per week he had large UI episodes that soaked his outwear. Also, he complained of inability to delay voiding, and UI with walking to the bathroom, sit to stand, lifting, coughing, and sneezing.

For the patients’ urge UI symptoms, behavioral interventions were utilized. The patient completed PFM contractions to inhibit detrusor contractions and suppress urgency (urge control technique). Educating the patient on correct PFM contraction isolation was a very important component of this patients’ treatment. Verbal, digital, and surface electromyography (sEMG) techniques were used to ensure correct PFM contraction and to reduce Valsalva. Clinical decision making for home exercise program utilized dominant PFM fiber types and the patients’ performance on the PERFECT PFM strength testing system described by Laycock. (External Urethral Sphincter is predominantly Type II fast twitch muscle fiber in males and Levator Ani is predominantly Type I slow twitch.) For the home program, the patient completed progressive reps and sets of 10” (targets slow twitch) and 2” (targets fast twitch) PFM isometrics in supine progressing to standing. (There is a chart with additional details on PFM home program for each visit in the case report.) Additionally, instruct and use of “the knack” (volitional PFM contraction before and during cough or other physical exertions to prevent UI) for activities that the patient usually had UI with including sit to stand transfer, lifting, coughing, and sneezing was essential for the patients’ symptoms. PFM coordination training with sEMG helped reduce his accessory muscle recruitment patterns and Valsalva. Bladder retraining and lifestyle recommendation were important (per his 3-day bladder diary) as he was consuming 3 cups of coffee and 4 cups or more of tea a day, likely contributing to urgency and urge UI symptoms. Also, he was informed regarding the effect of obesity on UI (as his BMI was 35.9 placing him in the obese range) and that modest amounts of weight loss maybe sufficient for UI reduction. Abdominal exercises targeting Transversus Abdominus were also prescribed for their role in core support with PFM’s. Lastly, electrical stimulation was not included in this patients’ plan of care due to the patients’ cardiac history and pacemaker, as well as, he could initiate PFM contraction and utilize urge control techniques appropriately.

The outcome for this patient was positive. He attended 5 PT sessions over a 3-month period. He did have to cancel two appointments between the 4th and 5th visits due to an emergency surgery to place two cardiac stents. He had reduced urinary leakage indicated by reduced undergarment changes and reduced pad usage per day. His pads were less saturated and he no longer had leakage that spread to his outwear. He had a 50% reduction in UI episodes reported on his bladder diary and a 50% reduction in nocturia from 4 times to 2 times per night. He reported reduced daily urinary frequency from 7 to 5 times per day with no instances of severe urgency. He demonstrated improved PERFECT score of 4, 10, 8, 10 (initially his score was 2, 5, 3, 5) indicating improved PFM strength and endurance. Also, he had improved PFM coordination as he could isolate PFM contraction without Valsalva or accessory muscle activation. He also had one strength grade improvement with abdominal strength. All that being said, most importantly, this patient had improved rating on the outcome questionnaire (International Continence Society male Short Form (ICSmaleSF)) at discharge indicating improved quality of life. At initial evaluation, this patient rated “a lot” (3 on ICSmaleSF) when asked how much the urinary symptoms interfered with his life, at discharge he reported “not at all” (0 on ICSmaleSF).

One component to this case that I found fascinating was the duration of time that had passed since this patients’ prostatectomy. It had been 10 years since this patient had his surgical procedures. He had never been offered physical therapy or knew about it as a possible treatment for his symptoms. Additionally, that he could have such success with improvements in voiding and incontinence function, as well as improved quality of life as long as 10 years’ post-prostatectomy.

This case report is a comprehensive glimpse of what physical therapy assessment and treatment may look like for a patient with urinary dysfunction following radical prostatectomy. This patient had great improvements with positive changes enhancing his quality of life. So, if you are considering adding treatment of this population to your practice consider attending Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation, available this July in Annapolis, MD or September in Seattle, WA.

"Cancer Among Men", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Roscow, A. S., & Borello-France, D. (2016). Treatment of Male Urinary Incontinence Post–Radical Prostatectomy Using Physical Therapy Interventions. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 40(3), 129-138.