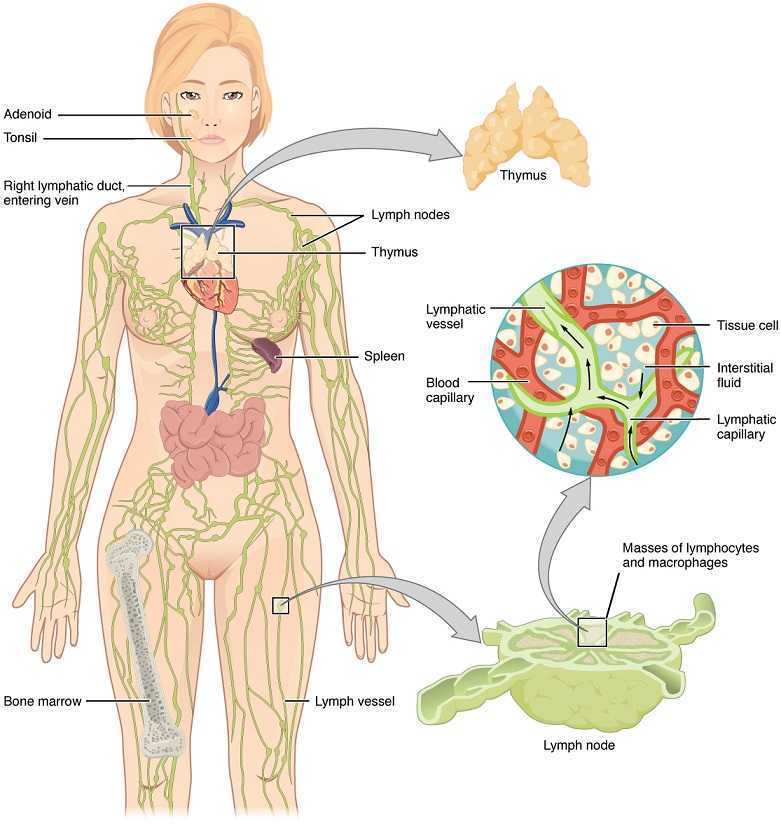

Lymphedema with regards to women’s health is most commonly associated with breast cancer. Upper extremity lymphedema can be limiting and painful without a doubt, and I have seen women suffering from irritating edema and limited shoulder range of motion and function after radical mastectomy. However, we may not always consider lower extremity lymphedema which can occur as a result of urogenital cancers and their treatments. Our knowledge and skilled hands can impact the quality of life of these patients who may seek treatment for their post-cancer complications.

Mitra et al., published a 2016 retrospective study on lymphedema risk post radiation therapy in endometrial cancer. They considered 212 endometrial cancer survivors, and 7.1% who received adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy developed lower extremity lymphedema after treatment, whether they had chemotherapy or not. Finding at least 1 positive pathological lymph node was directly correlated with an increased risk of lymphedema, regardless of attempts to control pelvic lymph-node dissection. These statistics encourage finding prophylactic measures to take for stage III endometrial cancer patients to minimize the risk for long-term lymphedema. Regarding treatment for lower extremity lymphedema, this paper discussed compression stocking use, pneumatic compression stockings, and complex decongestive therapy, an intensive regimen of physical therapy and massage that is unfortunately not easily accessible for a majority of patients. The authors encouraged future research on the efficacy of exercise and compression for lymph node positive patients.

Mitra et al., published a 2016 retrospective study on lymphedema risk post radiation therapy in endometrial cancer. They considered 212 endometrial cancer survivors, and 7.1% who received adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy developed lower extremity lymphedema after treatment, whether they had chemotherapy or not. Finding at least 1 positive pathological lymph node was directly correlated with an increased risk of lymphedema, regardless of attempts to control pelvic lymph-node dissection. These statistics encourage finding prophylactic measures to take for stage III endometrial cancer patients to minimize the risk for long-term lymphedema. Regarding treatment for lower extremity lymphedema, this paper discussed compression stocking use, pneumatic compression stockings, and complex decongestive therapy, an intensive regimen of physical therapy and massage that is unfortunately not easily accessible for a majority of patients. The authors encouraged future research on the efficacy of exercise and compression for lymph node positive patients.

Shaitelman et al. presented a review of the progress made in the treatment and prevention of cancer-related lymphedema (2015). They stated gynecologic cancer treatment is associated with 25% incidence of lymphedema. Endometrial cancer had 1%, cervical cancer had 27%, and vulvar cancer had 30% incidence specifically. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) can be an important part of cancer treatment, as lymphedema incidence was shown to average 9%. With treatment of genitourinary cancers, lymphedema occurred in 4% patients with prostate cancer, 16% patients with bladder cancer, and 21% patients with penile cancer. Shown to decrease limb volume and improve quality of life, the current standard of care is complete decongestive therapy (CDT). These authors state CDT involves the use of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), bandaging on a daily basis, skin care, exercise, and a 3-phase protocol of compression. The use of SLNB helps identify the risk of lymphedema post cancer treatment; however, clinicians need to be aware of the signs and symptoms of lymphedema so the affected patient can be recognized early and referred to the appropriate specialist for treatment.

We may be referred patients with the confirmed diagnosis of lymphedema, but often we see post-cancer patients for rehab who develop lymphedema months after radiation or chemotherapy. Any healthcare professional involved with regular treatment of a cancer-surviving patient needs to have a keen sense for diagnosing and properly taking care of lymphedema. Courses such as “Lymphatics and Pelvic Pain: New Strategies” can open a whole new avenue for understanding what patients may need from us following urogenital and genitourinary cancers. Why not be prepared to face with knowledge and skill whatever pathology our patients present?

Mitra, D., Catalano, P.J., Cimbak, N., Damato, A.L., Muto, M.G., & Viswanathan, A.N. (2016). The Risk of Lymphedema After Postoperative Radiation Therapy in Endometrial Cancer. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology, 27(1), e4.

Shaitelman, S.F., Cromwell, K.D., Rasmussen, J.C., Stout, N.L., Armer, J.M., Lasinski, B.B., & Cormier, J.N. (2015). Recent Progress in Cancer-Related Lymphedema Treatment and Prevention. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 65(1), 55-81.

During labor, I had no problem breathing out. My hang up came when I had to inhale - actually oxygenate my blood and maintain a healthy heart rate for my almost newborn baby. When extra staff filled the delivery room, and an oxygen mask was placed over my face, my husband remained calm but later told me how freaked out he was. He was watching the monitors that showed a drop in my vitals as well as our baby’s. In retrospect, I wonder if practicing yoga, particularly the breathing techniques involved with pranayama practice, could have prevented that moment.

A research article by Critchley et al., (2015) broke down breathing to a very scientific level, determining the consequences of slow breathing (6 breaths/minute) versus induced hypoxic challenges (13% inspired O2) on the cardiac and respiratory systems and their central neural substrates. Functional magnetic resonance imaging measured the 20 healthy subjects’ specific brain activity during the slow and normal rate breathing. The authors mentioned the controlled slow breathing of 6 breaths/minute is the rate encouraged during yoga practice. This rate decreases sympathetic activity, lessening vasoconstriction associated with hypertension, and it prevents physiological stress from affecting the cardiovascular system. Each part of the brain showed responses to the 2 conditions, and the general conclusion was modifying breathing rate impacted autonomic activity and improved both cardiovascular and psychological health.

A research article by Critchley et al., (2015) broke down breathing to a very scientific level, determining the consequences of slow breathing (6 breaths/minute) versus induced hypoxic challenges (13% inspired O2) on the cardiac and respiratory systems and their central neural substrates. Functional magnetic resonance imaging measured the 20 healthy subjects’ specific brain activity during the slow and normal rate breathing. The authors mentioned the controlled slow breathing of 6 breaths/minute is the rate encouraged during yoga practice. This rate decreases sympathetic activity, lessening vasoconstriction associated with hypertension, and it prevents physiological stress from affecting the cardiovascular system. Each part of the brain showed responses to the 2 conditions, and the general conclusion was modifying breathing rate impacted autonomic activity and improved both cardiovascular and psychological health.

Vinay, Venkatesh, and Ambarish (2016) presented a study on the effect of 1 month of yoga practice on heart rate variability in 32 males who completed the protocol. The authors reported yoga is supposed to alter the autonomic system and promote improvements in cardiovascular health. Not just the breathing but also the movements and meditation positively affect mental health and general well-being. The subjects participated in 1 hour of yoga daily for 1 month, and at the end of the study, the 1 bpm improvement in heart rate was not statistically significant. However, heart rate variability measures indicated a positive shift of the autonomic system from sympathetic activity to parasympathetic, which reduces cortisol levels, improves blood pressure, and increases circulation to the intestines.

Bershadsky et al., (2014) studied the effect of prenatal Hatha yoga on cortisol levels, affect and depression in the 34 women who completed pre, mid, and post pregnancy saliva tests and questionnaires. While levels of cortisol increase naturally with pregnancy, yoga was found to minimize the mean levels compared to the days the subjects did not participate in yoga. After a single 90-minute yoga session, during which breathing was emphasized throughout the session, women had higher positive affect; but, the cortisol level was not significantly different from the control group. Overall, the authors concluded yoga had potential to minimize depression and cortisol levels in pregnancy.

Considering the positive effect of slow breathing practiced in yoga, the positive shift in the autonomic nervous system function and the decrease in cortisol levels, yoga is gaining credibility as an effective adjunct to treatment during pregnancy. If a woman enters the delivery room with a solid practice of slow breathing under her belt, she may be equipped to handle the intensity of contractions and the pain of pushing a little better. Yoga may help a woman breathe for her life and her baby’s as well.

If you're interested in learning more about yoga for pregnant patients, consider attending Yoga as Medicine for Pregnancy with Ginger Garner, PT, DPT, ATC/LAT, PYT. The next opportunity is in Fort Lauderdale, FL on January 28th and 29th, 2017. Don't miss out!

Critchley, H. D., Nicotra, A., Chiesa, P. A., Nagai, Y., Gray, M. A., Minati, L., & Bernardi, L. (2015). Slow Breathing and Hypoxic Challenge: Cardiorespiratory Consequences and Their Central Neural Substrates. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0127082.

Vinay, A., Venkatesh, D., & Ambarish, V. (2016). Impact of short-term practice of yoga on heart rate variability. International Journal of Yoga, 9(1), 62–66.

Bershadsky, S., Trumpfheller, L., Kimble, H. B., Pipaloff, D., & Yim, I. S. (2014). The effect of prenatal Hatha yoga on affect, cortisol and depressive symptoms. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 20(2), 106–113.

Myofascial release (MFR) can be one of your greatest treatment tools as a pelvic rehabilitation practitioner. Just in case you don’t think about fascia often here are a couple helpful things to remember. Fascia is the irregular connective tissue that covers the entire body, and it is the largest sensory system in the body, making it highly innervated. The mobilizing effect of MFR techniques occurs by stimulating various mechanoreceptors within the fascia (not by the actual force applied). MFR techniques can help to reduce tissue tension, relax hypertonic muscles, decrease pain, reduce localized edema, and improve circulation just to name a few physiological effects.

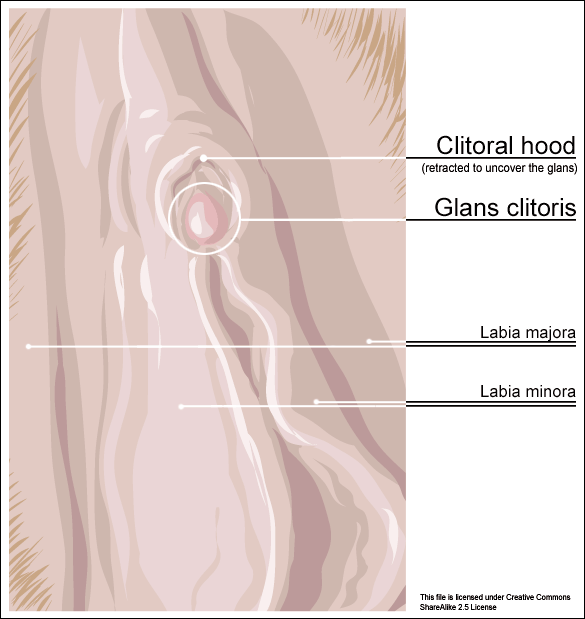

An interesting case report published in 2015 by the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1 offers a wonderful example of how a physical therapist used specific MFR techniques for a patient with clitoral phimosis and dyspareunia. The specific MFR techniques used helped to provide relief and restore mobility to the pelvic tissues for this patient.

An interesting case report published in 2015 by the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1 offers a wonderful example of how a physical therapist used specific MFR techniques for a patient with clitoral phimosis and dyspareunia. The specific MFR techniques used helped to provide relief and restore mobility to the pelvic tissues for this patient.

Clitoral phimosis is adherence between the clitoral prepuce (also known as the clitoral hood) and the glans. This condition can be the result of blunt trauma, chronic infection, inflammatory dermatoses, and poor hygiene. In this case report, the 41-year-old female patient had sustained a blunt trauma injury to the vulva (when her toddler son charged, contacting his head forcibly into her pubic region). She presented to physical therapy with complaints of dyspareunia, low back pain, a bruised sensation of her pubic region, vulvar pain provoked by sexual arousal, decreased clitoral sensitivity, and anorgasmia. The physical therapist completed an orthopedic assessment for the lower quarter (including spine and extremities), as well as a thorough pelvic floor muscle assessment.

Treatment for this patient addressed not only the pelvic complaints, but the lower quarter complaints as well. A detailed treatment summary for each visit is outlined in the case report. The clitoral MFR and stretching was performed by applying a small amount of topical lubricant to the clitoral prepuce. Then, a gloved finger or a cotton swab was used to stabilize the clitoris, a prolonged MFR or sustained stretch was applied in the direction away from the fixated clitoris by the therapist’s other finger. The therapist applied this technique along the entire length of the prepuce. The other physical therapy interventions this patient was treated with were stretching, joint mobilization, muscle energy techniques, transvaginal pelvic floor muscle massage, clitoral prepuce MFR techniques, biofeedback, Integrative Manual Therapy (IMT) techniques, nerve mobilization, and therapeutic and motor control exercises. Additionally, between the physical therapy evaluation and the second visit the patient did use topical Clobetasol 0.05% cream (commonly prescribed for vulvar dermatitis issues such as Lichen Sclerosis) for 30 days with no change to her clitoral phimosis.

After 11 sessions, the patient had resolution of dyspareunia, vulvar pain, pubic pain, and reduced low back pain. Also, the patient had 100% restored mobility of the clitoral prepuce, as well as normalized clitoral sensitivity and clitoral orgasm. The patient felt these improvements were still present at her 6-month follow-up interview over the phone. Current medical management for clitoral phimosis is surgical release or topical/injectable corticosteroids. Having a conservative treatment option, such as MFR, for this condition can be helpful for patients. As with most evolving treatment techniques, more research and studies are appropriate.

Not one health care professional had ever assessed the fascial mobility of the clitoris until this physical therapist did. This case report is an example of how MFR techniques can be effective treatment tools for your patients with pelvic disorders and a good reminder to check the fascial mobility of the pelvic tissues.

Morrison, P., Spadt, S. K., & Goldstein, A. (2015). The Use of Specific Myofascial Release Techniques by a Physical Therapist to Treat Clitoral Phimosis and Dyspareunia. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 39(1), 17-28.

One of my dear patients was recently diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos sydrome (EDS). The diagnosis brought a sense of relief for sweet Katie who for years struggled with numerous health problems and was often misunderstood and under cared for by the medical community. Katie was referred to me 2 years ago at 28 for pelvic pain, endometriosis and IC. Upon exam we also discovered a significant elimination disorder and paradoxical elimination. Katie regularly timed her elimination and was spending at times up to 2 hours trying to empty her bowels. As we worked together we uncovered bilateral hip dysplasia, left hip labral tear, ilioinguinal and pudendal neruralgia and POTS (Postural Orthostatic Hypotension Syndrome). Katie already had a history of anxiety and depression but managed well with good family and friend support. When the diagnosis of EDS came, she finally felt like she had an explanation for why her body is like it is. This brought great relief as well as the knowledge that her condition was genetic and her conditions needed to be managed as best as possible to give her the most function, but would likely never be fully resolved.

In her book "A Guide to Living with Ehler's Danlos Syndrome" Isobel Knight does a beautiful job outlining the various genetic subtypes of Ehlers Danlos but also highlighting the fact that EDS hypermobility type (Type III) does not just affect the connective tissue in the musculoskeletal sytem leading to joint instability and hypermoblity, muscle tears, dislocations, subluxations, hip dysplasia and flat feet. EDS can also affect the body's systemic collagen leading to increased risk for endometriosis, POTS, Renauds, bladder problems, fibromyalgia, headaches, restless legs, ashtma, consitpation, bloatedness, prolapse, IBS symptoms, anxiety, depression and learning difficulties. She notes that some people have only a few of these systemic symptoms while others may be more affected. Per Isobel: "it is important that all symptoms are treated seriously and not ridiculed and that the appropriate medical support is given to them when necessary."

In her book "A Guide to Living with Ehler's Danlos Syndrome" Isobel Knight does a beautiful job outlining the various genetic subtypes of Ehlers Danlos but also highlighting the fact that EDS hypermobility type (Type III) does not just affect the connective tissue in the musculoskeletal sytem leading to joint instability and hypermoblity, muscle tears, dislocations, subluxations, hip dysplasia and flat feet. EDS can also affect the body's systemic collagen leading to increased risk for endometriosis, POTS, Renauds, bladder problems, fibromyalgia, headaches, restless legs, ashtma, consitpation, bloatedness, prolapse, IBS symptoms, anxiety, depression and learning difficulties. She notes that some people have only a few of these systemic symptoms while others may be more affected. Per Isobel: "it is important that all symptoms are treated seriously and not ridiculed and that the appropriate medical support is given to them when necessary."

It seems that EDS is becoming more widely recognized. As rehabilitation specialists we should be alert to problems stemming from joint hypermobility when we notice how our patients position themselves. Often legs are curled up or double crossed. Upon questioning we might find that the patient has a history of being "double jointed" or was able to do "party tricks" with their bodies. The Bighton scale is a test of joint hypermobility which we should all be familiar with. It is also important to note that a patient may have hypermobility without having EDS, and that EDS is usually associated with pain. A rheumatologist, or in Katie's case a geneticist, can help confirm a suspected EDS diagnosis.

If you have a patient with hypermobliiy or with EDS, know that their ability to know where their body is in space is limited as their joints have much more range of motion than normal. The proprioceptors do not fire well at mid range and the patient will have to be trained to become accustomed to neutral joint positions. This was really painful for Katie and it took a huge mental and physical effort. She is getting stronger now and it is becoming easier to achieve. Stretching and soft tissue massage can feel really good when your muscles have to work so hard to maintain your joints in healthy positions. Patients should be instructed to not stretch into end range and also not "hang out" on their ligaments. Some patients may have to begin just with isometrics. I used Sara Meeks' program for safe and effective floor exercise with Katie. The floor gave her support while she strengthened her core muscles. Then she was able to progress to seated and seated on a ball as well as standing exercises. She loves the body blade! Yoga, Pilates, exercise in water can be effective for strength, propriception and movement reeducation. Mirrors are helpful for increasing position sense.

It is also helpful to note that even patients with EDS may be hypermobile in some joints and hypomobile in others. Isobel reports that her SI joints were extremely unstable while her thoracic spine was very rigid to the point that her lung capacity was affected. Having her therapist work on the hypomobility and doing breath work was life changing.

As pelvic health therapists and rehabilitation providers we may be the first professional to suspect EDS in a patient. There is a great deal that we and the greater medical and holistic community can do to help patients with EDS lead lives with less pain and dysfunction.

In the 80’s, I would stand in my older sister’s bedroom wearing a button-down, collared shirt under a sweater and beg her to “fix me.” I felt stuck and wanted to cry until she twisted the shirt and loosened the snags of the knitted covering and made the outfit lay properly together. The myofascial system can often make us feel the same way if what’s lying underneath the intricately woven network of tissue has trigger points and inflammatory mediators rearing their ugly heads. When myofascial restrictions strike the pelvic region, every move a person makes can tug at the affected fascia and magnify the pain.

How do we know if someone has myofascial pain syndrome? Itza et al., (2015) published a study on turns-amplitude analysis (TAA) efficacy for diagnosing the syndrome in patients with chronic pelvic pain. The 128 subjects (64 with chronic pelvic pain and 64 healthy controls) underwent electromyogram (EMG) tests conducted in the levator ani muscle and the external anal sphincter. The mean TAA data was analyzed automatically, and an increase in the score was considered to be positive, while a decrease was negative. An increased TAA was found in 86% of the patients (no difference between men and women), and 100% of the control subjects displayed no increase in TAA. This study showed TAA to be an effective means by which to diagnose myofascial pain syndrome of the pelvic floor.

How do we know if someone has myofascial pain syndrome? Itza et al., (2015) published a study on turns-amplitude analysis (TAA) efficacy for diagnosing the syndrome in patients with chronic pelvic pain. The 128 subjects (64 with chronic pelvic pain and 64 healthy controls) underwent electromyogram (EMG) tests conducted in the levator ani muscle and the external anal sphincter. The mean TAA data was analyzed automatically, and an increase in the score was considered to be positive, while a decrease was negative. An increased TAA was found in 86% of the patients (no difference between men and women), and 100% of the control subjects displayed no increase in TAA. This study showed TAA to be an effective means by which to diagnose myofascial pain syndrome of the pelvic floor.

What are some treatments being researched? Anderson et al., (2016) conducted a study on using a multi-modal protocol with an internal myofascial trigger point wand to treat men and women with chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS). After 6 days of training, male and female subjects with CPPS engaged in 6 months of pelvic floor trigger point release with an internal trigger point device that was self-administered in combination with paradoxical relaxation training. In the end, women and men subjects experienced similar reduction of symptoms as trigger point sensitivity decreased significantly.

Adelowo et al., (2013) explored the efficacy of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) for treatment of myofascial pelvic pain via a retrospective cohort study. Trigger points and pelvic floor hypertonicity were identified and confirmed with digital palpation. Twenty-nine women were assessed after intralevator injection with Botox A, and 79.3% reported reduction of pain. Botox A was deemed an effective and safe intervention with only mild, spontaneously resolving side effects occurring in 8 of the patients.

In 2012, Fitzgerald et al. studied the difference in outcomes between myofascial physical therapy (MPT) versus global therapeutic massage (GTM) for patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Of the 81 women randomly allocated to the two treatment groups, the MPT group had the greater response with 59% reporting moderate or marked improvement in symptoms (compared to 26% in the GTM group). Ultimately, myofascial physical therapy was considered beneficial for pelvic disorders.

Being able to adjust an outward snag such as a twisted sweater or stocking is much less complicated than deciphering and untangling the internal myofascial dysfunctions in the pelvis. When you are without an EMG, high-tech internal wands, or Botox, it is up to your hands and keen sensibility to detect the presence of the trigger points and release the restrictions. Thankfully, courses like “Mobilization of the Myofascial Layer: Pelvis and Lower Extremity” can guide you towards greater efficacy in this endeavor.

Itza, F., Zarza, D., Salinas, J., Teba, F., & Ximenez, C. (2015). Turn-amplitude analysis as a diagnostic test for myofascial syndrome in patients with chronic pelvic pain. Pain Research & Management : The Journal of the Canadian Pain Society, 20(2), 96–100.

Anderson, R.U., Wise, D., Sawyer, T. et al. (2016). Equal Improvement in Men and Women in the Treatment of Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome Using a Multi-modal Protocol with an Internal Myofascial Trigger Point Wand. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback. 41:215.

ADELOWO, A., HACKER, M. R., SHAPIRO, A., Modest, A. M., & ELKADRY, E. (2013). Botulinum Toxin Type A (BOTOX) for Refractory Myofascial Pelvic Pain. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, 19(5), 288–292.

FitzGerald, M., Payne, C., Lukacz, E., Yang, C., Peters, K., Chai, T., … Nyberg, *LM. (2012). Randomized Multicenter Clinical Trial of Myofascial Physical Therapy in Women with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome (IC/PBS) and Pelvic Floor Tenderness. The Journal of Urology, 187(6), 2113–2118.

Faculty member Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC has written in to encourage us all to practice kindness and patience. A positive attitude can affect more than just your friends and family; your patients will benefit in so many ways as well!

First a little personal story. Several years ago my daughter was going through a tough time and we worked with a child psychologist. He was a wonderful man who taught my husband and I so much about how to raise a challenging kiddo. The foundation of what we needed to learn was the power of positive. People need nine (or so) positive interactions to override a negative one. Poor kid was definitely at a deficit! So if she did something that needed correcting, we were to give her a chance at a "do over" where sometimes we had to coach her to choose a better action. After she got it right, we lavished praise on our little pumpkin. And would you believe, not only did all that positiveness make a difference for her, it made a difference for her parents too!

First a little personal story. Several years ago my daughter was going through a tough time and we worked with a child psychologist. He was a wonderful man who taught my husband and I so much about how to raise a challenging kiddo. The foundation of what we needed to learn was the power of positive. People need nine (or so) positive interactions to override a negative one. Poor kid was definitely at a deficit! So if she did something that needed correcting, we were to give her a chance at a "do over" where sometimes we had to coach her to choose a better action. After she got it right, we lavished praise on our little pumpkin. And would you believe, not only did all that positiveness make a difference for her, it made a difference for her parents too!

Now back to the clinical. Just about two years ago I had the privilege of teaching with Nari Clemons. We taught PF2B together. Nari said something during one of her lectures that revolutionized my PT practice. She challenged us in lab to find three positive things about our lab partner and share those things before recognizing any deficits. How many times do we get finished with an evaluation and sit down with a patient and list all the things we found that need correction or help, perhaps drawing on our Netter images to fully illustrate the parts of their body that are broken or need fixing.

So I changed things up a bit and started remarking about the positive things I found on exam. "Wow, your hips are really strong and stable." "You've got a really coordinated breathing pattern, that is going to work in your favor." "You're pelvic muscles are really strong." and then later drawing on those positives outline how we could use the patient's strengths to help them overcome their challenges. "Because you have a great breathing strategy we are going to use that to help your whole nervous system to relax which with help your pelvic floor relax," for example.

The results were shocking. Person after person told me how much it meant to them to leave feeling positive and hopeful. One delightful woman who I saw for a diastasis had amazing leg muscles and I told her so. When she returned she said, "I've felt so self conscious about my flabby belly, but this week all I could think about were my strong leg muscles. Thanks for telling me that."

We do know is that our attitudes and beliefs as providers influence not only our clinical management but patient outcomes as well. Darlow et. al. performed a comprehensive literature review looking at how attitudes and beliefs among health care providers affected outcomes in patients with low back pain and discovered, "There is strong evidence that health care provider beliefs about back pain are associated with the beliefs of their patients."

Why not use that truth to our advantage and be positive? Would love to hear about your experiences!

Join Jennafer at one of her upcoming courses, Pelvic Floor Level 2B - Trenton, NJ - February 24-26, 2017, Pelvic Floor Series Capstone - Arlington, VA - May 5-7, 2017, Pelvic Floor Series Capstone - Columbus, OH - August 18-20, 2017, and Pelvic Floor Series Capstone - Tampa, FL - December 2-4, 2016.

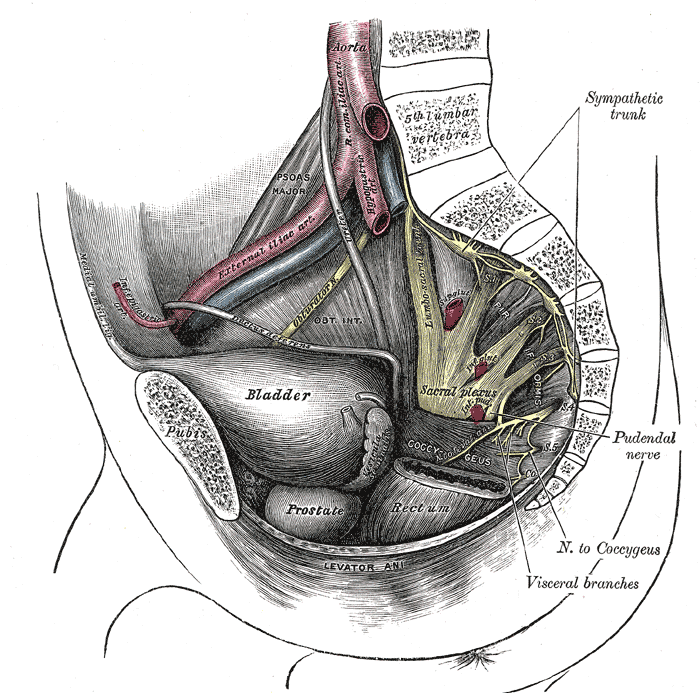

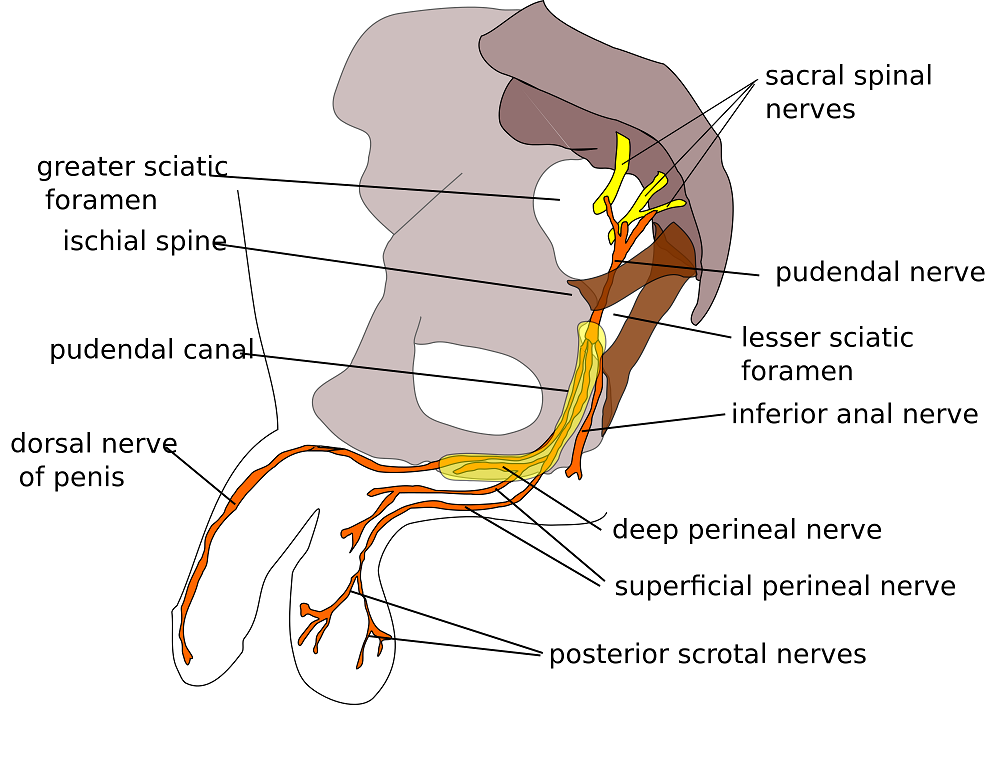

Herman & Wallace are pleased to announce a new course! Pudendal Neuralgia and Nerve Entrapment will be presented by Michelle Lyons in Freehold, NJ on June 17/18, 2017. We chatted with Michelle about this new course to hear her thoughts and get an overview of the contents

There are a number of courses which I teach for Herman & Wallace including Pelvic Floor Level 2A, my Male Oncology and Female Oncology and the The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor courses. They all have sections on pudendal dysfunction and it’s an area that participants always want more information on. There’s no other nerve that elicits the same interest, discussion and confusion! Nobody really talks about iliohypogastric or ulnar neuralgia with the same intensity as pudendal neuralgia, and no other nerve dysfunction provokes the same amount of controversy and mystery.

There are a number of courses which I teach for Herman & Wallace including Pelvic Floor Level 2A, my Male Oncology and Female Oncology and the The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor courses. They all have sections on pudendal dysfunction and it’s an area that participants always want more information on. There’s no other nerve that elicits the same interest, discussion and confusion! Nobody really talks about iliohypogastric or ulnar neuralgia with the same intensity as pudendal neuralgia, and no other nerve dysfunction provokes the same amount of controversy and mystery.

When I was approached about developing this course for the Institute, I jumped at the opportunity. For those who don’t know me, I really like to bring an integrative approach to my work, both clinically and educationally. I have experience and training in nutrition, coaching, yoga, Pilates and mindfulness as a therapeutic intervention and I think these fit really well alongside traditional pelvic rehab approaches. Manual therapy and bespoke exercise prescription will always be the bedrock of my approach, but sometimes our patients, especially those with chronic pain, need some extra support. I’m also a bit of an anatomy nerd, so the chance to delve deep into pelvic neuroanatomy and neurodynamics was too much to resist!

I think this is a Golden Age in pelvic health – there are so many great learning opportunities and resources available to us to help serve our patients better. Another area that I find fascinating to explore is the huge leap we have made in understanding neuroscience and the role of pain education when it comes to chronic pelvic pain. I’m a big fan of the work done by Moseley and Butler in Australia, and I love how authors like Hilton, Vandyken and Louw have transferred that to the world of pelvic pain in their book "Why Pelvic Pain Hurts". The language that we use is very important when discussing how the brain responds to chronic pain and the changes that occur with central sensitization. We never want our patients to feel as if we think their pain is ‘all in their heads’ but at the same time, we need to be able to incorporate strategies such as motor imagery and graded exposure and to demonstrate to our patients that"…it is important to acknowledge that chronic pain need not involve any structural pathology" (Aronoff 2016).

Those are some of the discussions we’ll be having in Freehold, NJ next June – I hope you’ll come and join the conversation!

"What Do We Know About the Pathophysiology of Chronic Pain? Implications for Treatment Considerations" Aronoff, GM Med Clin North Am. 2016 Jan;100(1):31-42

"Why Pelvic Pain Hurts: Neuroscience Education for Patients with Pelvic Pain" Hilton, Vandyken, Louw, International Spine and Pain Institute (May 28, 2014)

With menopause and the hormonal shifts that take place, some women suffer more than others with symptoms such as hot flashes. If you have ever been near someone during a hot flash, you know that this curious condition is more than feeling a little hot under the collar. During a hot flash, women will suddenly disrobe, wake from a deep sleep covered in sweat (so much so that they have to change the sheets!), or otherwise appear distressed and oftentimes suffer interference in whatever activity in which they were engaging. As we reported in an earlier post, women on average may have hot flashes for 5 years after the date of her last period. Some women (up to 1/3 in the referenced study) will report hot flashes for 10 or more years after menopause.

Hot flashes and night sweats also significantly disrupt sleep, according to research by Baker and colleagues. Menopausal women with insomnia may also have higher levels of psychologic, somatic, vasomotor symptoms, and score lower on the Beck Depression Inventory, and sleep efficiency and duration scores. Poor sleep can be associated with morbidity such as hypertension, stroke, diabetes and depression, so interrupted sleep is more than an inconvenience, but potentially a serious health issue.

Hot flashes and night sweats also significantly disrupt sleep, according to research by Baker and colleagues. Menopausal women with insomnia may also have higher levels of psychologic, somatic, vasomotor symptoms, and score lower on the Beck Depression Inventory, and sleep efficiency and duration scores. Poor sleep can be associated with morbidity such as hypertension, stroke, diabetes and depression, so interrupted sleep is more than an inconvenience, but potentially a serious health issue.

A more recent study linked anxiety as a potential risk factor for menopausal hot flashes. In 233 women who are premenopausal at baseline and who were followed for at least a year after their final menstrual cycle, anxiety symptoms, hormone levels, hot flashes and other psychosocial variables were assessed. During the 14 year follow-up 72% of the women reported having moderate to severe hot flashes, and the researchers correlated somatic anxiety as a potential predictive association with anxiety. Somatic anxiety refers to the physical symptoms of anxiety, such as stomach ache, increased heart rate, sweating, muscle aches.

In order to help a woman support her wellness during menopausal transitions, being able to address somatic anxiety and conditions like hot flashes is imperative. Teaching skills such as breathing, relaxation training, meditation, or mindfulness may positively impact the anxiety, and therefore have the potential to reduce hot flashes and other adverse symptoms. Herman & Wallace's Menopause Rehabilitation and Symptom Management course is an excellent opportunity to learn some of these valuable skills.

Baker, F. C., Willoughby, A. R., Sassoon, S. A., Colrain, I. M., & de Zambotti, M. (2015). Insomnia in women approaching menopause: beyond perception. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 60, 96-104.

Freeman, E. W., & Sammel, M. D. (2016). Anxiety as a risk factor for menopausal hot flashes: evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging cohort. Menopause, 23(9), 942-949.

Freeman, E. W., Sammel, M. D., & Sanders, R. J. (2014). Risk of long term hot flashes after natural menopause: Evidence from the Penn Ovarian Aging Cohort. Menopause (New York, NY), 21(9), 924.

The following comes from a male patient who wanted to share his story about finding care for his pelvic floor dysfunction. His story highlights the important role pelvic rehab practitioners can play, and why we need to continue training more therapists in this field.

I’m 65 year old male and I developed pudendal neuralgia and pelvic floor issues as a result of an accident about four years ago. Shortly after my accident I started to experience pain in my testicles and perineum. At the time, I did not think that one had anything to do with the other. I made an appointment with my urologist who did an ultrasound and assured me that there was nothing physically wrong. I don’t think my testicles quite believe that but mentally I felt relieved. But the pain persisted and started to spread. Now it was also in my groin and penis. I was also having problems with chronic constipation, urinary retention and erectile dysfunction. Since I did have back surgery years ago I started to suspect my low back was causing the problem. I made an appointment with a well-respected orthopedic surgeon in New York. While he gave me his analysis with regards to my back problems he clearly avoided addressing the pelvic issues. I left there feeling lost. Suffice it to say that over the course of the next couple of years I saw several other specialists who either skirted around the issue or told me that nothing was wrong. A couple of years passed but the pelvic issues just continued to get worse and worse. I started seeing a new primary care physician who indicated that perhaps the source of the pelvic pain was coming from the pudendal nerve and felt that physical therapy might help. She gave me a prescription for physical therapy to evaluate for pudendal nerve.

Well, I have a diagnosis now so I start researching pudendal neuralgia and land on the Pudendal Hope website. Wow! What an eye opener that was. I’m reading the information on the website and it was like I had an epiphany. I realized that I was not going crazy and that Pudendal Neuralgia and pelvic pain are very real issues.

Well, I have a diagnosis now so I start researching pudendal neuralgia and land on the Pudendal Hope website. Wow! What an eye opener that was. I’m reading the information on the website and it was like I had an epiphany. I realized that I was not going crazy and that Pudendal Neuralgia and pelvic pain are very real issues.

OK, so where do I go from here? With prescription in hand I’ll make an appointment with a physical therapist that deals with pudendal neuralgia. Ha, I thought getting a diagnosis was tough but finding a physical therapist that treats pudendal neuralgia and pelvic issues was no easy task. To make things even more challenging, finding a physical therapist who treats men was even harder. I made a few calls and kept looking online without much success. Desperate to find a physical therapist that treats men, I sent an email off to a therapist in California asking if by some chance she could recommend a physical therapist here in New Jersey. As luck would have it, I got both a response and a referral. With that, I called Michelle Dela Rosa at Connect Physical Therapy. I had to wait about six weeks for an appointment but finally the day arrived. OK, so now, I had set my expectations. I’ll go for a few weeks of physical therapy, the pain will go away and it will be back to a normal life. Well, not so much… the journey and education were just getting started.

There are days when I am in so much pain that I ask myself if the pelvic therapy is really doing me any good. But then I reflect back to how things were before I started the therapy. Funny thing about pain… often times it makes us forget how things were in the past and shift our focus to the here and now. That being said, I quickly realize how much I have truly progressed since starting therapy.

So what have I learned? Well, the first thing is to understand the anatomy and how all the pelvic muscle groups and nerves are integrated. After all you can’t fix what you don’t know is broken. Therapy has certainly helped educate me in that respect; I’ve learned the importance of proper breathing and strengthen the core muscles. I know that when I was in pain I would tighten up the pelvic muscles and hold my breath which would only make things worse, as the muscles would get into a knot, and make it even more difficult to get relief. I’ve learned a whole new set of exercises that I now have in my arsenal to help fight this battle. To help me deal with the chronic constipation I’ve learned how to massage my abdomen to help move things along. For those folks dealing with chronic constipation, well, we all know what happens when we push just a little too hard… flare time! I could go on and on. I learned to use tools, such as the TheraWand, to help break the tension for those internal pelvic muscles. Pelvic therapy has taught me the importance and benefits of the proper use of cold packs, glides, exercise, breathing, relaxing the pelvic floor and on and on and on.

I was a bit embarrassed getting started but the prospect of relieving some of the pelvic pain and the professionalism of my therapist quickly turned my embarrassment into a non-issue.

I want to express my thanks and gratitude to all those physical therapists who have the courage and vision to take on this problem. You are truly making a difference in the lives of the people you are helping.

The following testimonial comes to us from Karen Dys, PTA. Karen recently attended the Care of the Pregnant Patient course, and she was inspired to send in the following review. Thanks for your contribution, Karen!

I have been working as a physical therapist assistant for 11 years and worked in a variety of settings. In the past two year I have become more focused on pelvic floor rehabilitation. During that time frame I have had a handful of pregnancy patient including being a pregnant woman myself. Since taking this course, my mind has been opened up of how I can treat my patients and educate them for their best future outcomes. I also can see now how I would have benefited myself if I knew some of these techniques that I’ve now learned. With knowing with my personal story and that my PT could have helped me more with avoiding bed rest and staying active longer with pregnancy, it has become my goal now to treat my pregnant patients differently. I am thankful for Herman and Wallace courses to gain these wonderful techniques to reach out and help so many people.

I have been working as a physical therapist assistant for 11 years and worked in a variety of settings. In the past two year I have become more focused on pelvic floor rehabilitation. During that time frame I have had a handful of pregnancy patient including being a pregnant woman myself. Since taking this course, my mind has been opened up of how I can treat my patients and educate them for their best future outcomes. I also can see now how I would have benefited myself if I knew some of these techniques that I’ve now learned. With knowing with my personal story and that my PT could have helped me more with avoiding bed rest and staying active longer with pregnancy, it has become my goal now to treat my pregnant patients differently. I am thankful for Herman and Wallace courses to gain these wonderful techniques to reach out and help so many people.

Within the first few moments of meeting the teacher at a continue education class I can tell if is going to be a good class or not. This course started out great with a very friendly and kind person. Sarah’s compassion and knowledge brightly shined throughout the weekend of teaching. It was very refreshing having a teacher who also has experienced some of the same problems are patients go through. It gave it a good personal perspective of how we can affect our patient outcomes.

One thing that I really appreciated at this course was the comfort level felt during the entire weekend. Right from the beginning Sarah made it clear that no question was stupid to ask. She explained that we are all at different learning stages in our career and that we are working together to gain this knowledge to be better therapists. I really appreciated hearing that and I know it made some of the new pelvic floor therapists feel more comfortable as well. I enjoyed having different labs throughout the weekend to practice these new techniques with new therapists of different educational levels. Sometimes I attend courses being more confused on techniques because the teacher, assistant or other course mates don’t have the time or knowledge to explain in further detail. At any of my Herman and Wallace courses I have attended, especially this one, I have not felt that way.

So I attended this wonderful class and now what? Well during the class I was thinking of my pregnant friends who are expecting multiples and how I can help them with their already felt extra swelling and low back pain. I also was thinking of some of my post-partum pelvic floor patients and how if I would have known some of this information sooner I could have impacted their pregnancy. Some things I would have changed were compression stock wear, abdominal binder/ brace wear, labor positioning techniques and strengthening more with education for post-partum phase. So now I have brought back to my company more knowledge of how to evaluate, assess more correctly and treat pregnancy patients. I have led a in-service for my coworkers who are primarily orthopedic based . They had a good take away of how to help patients with orthopedic complaints of pain who also happen to be pregnant.

I am thankful for this course I attended and look forward to making it a regular event I attend. Herman and Wallace courses never disappoint. Thank you.

Karen R Dys, PTA

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com/