As pelvic rehab providers, we may find it easy to talk to our patients about sexual function when it is a patient who comes to us with a sexually relevant problem or directly related diagnosis, such as dyspareunia or limited intercourse participation due to prolapse symptoms. However, are we talking to our other patients about sexual function? Are they talking to us about it? What about our orthopedic patients - are we routinely asking them about how their problem can affect their sexual function? Some recent studies found that 32% of patients planning to undergo a Total Hip Replacement (THR) had reported concerns about difficulties with sexual activityBaldursson, Wright. Was the fact that they could not participate in sexual activity due to the hip pain a driving factor when considering the hip replacement, maybe? Just because a patient doesn’t ask, does not mean that they don’t want to know how their orthopedic injury affects sexual function. Resuming sexual function is an important quality of life goal that is included on few outcome assessment forms, however, there are some that address this subject such as the Oswestry Disability Index for Low Back Pain. Discussion of this topic should be addressed more routinely than it is.

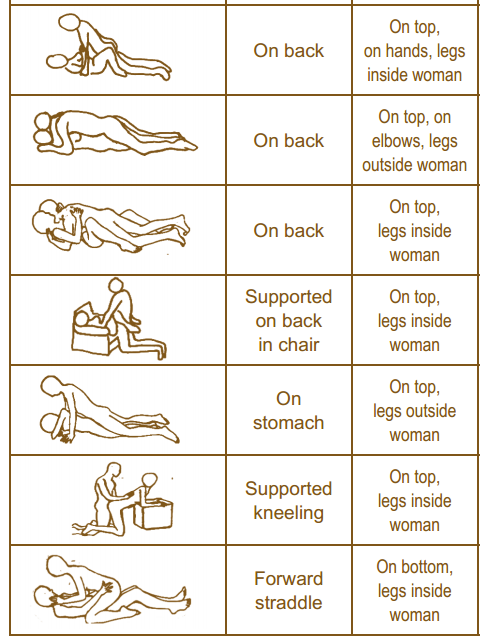

It is important to remember that just because a patient is not in our office for a directly related sexual problem, it is still important to at least open up the dialogue about sexual health. One study in 2013 had patients complete a questionnaire on their sexual function after undergoing a total hip or total knee replacement and 90% reported improved overall sexual functionRathod, et al.. We should try to make the conversation part of our routinely delivered information for a total joint replacement, for example when telling our THR patient, you can resume driving at 3-6 weeks (or when cleared by surgeon), you have Range of Motion precautions of avoiding internal rotation, hip flexion past 90 degrees, and hip adduction (crossing the legs) for the length specified by your surgeon (if it was a posterior approach THR), and you can resume sexual function at 3-6 weeks (or when cleared by the surgeon), or when you feel ready after that. It is important to give the patient some kind of guideline about when they can expect to resume sexual activity, however, always emphasize that it should be resumed when the patient is ready so they don’t feel pressured before they are ready. Also as pelvic rehab practitioners we can offer them guidance about what positions may be best for them when returning to sexual activity to put less strain on the prosthesis and hip as well as help them be comfortable. To continue with our example for THR (posterior approach) their precautions are likely to restrict hip flexion past 90 degrees, hip internal rotation, and adduction, so for a man or woman following THR lying on their back would be a safe position.

As physical therapists it is our job to provide guidance. Instead of telling people what not to do, helping them find a safe way to do things they want to do to maintain function should always be our goal. Sexual activity participation is definitely an important function for quality of life that is often overlooked and not discussed, so talk to your patient about it, they will likely appreciate it.

One useful tool to learn more about positioning for sexual activity is the Herman & Wallace product “Orthopedic Considerations for Sexual Activity.” It provides a great list of positions with pros and cons of each position, and is a helpful visual aid for your patients to help them return to sexual function safely with consideration of their respective injuries.

Baldursson, H., & Brattström, H. (1979). Sexual difficulties and total hip replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology, 8(4), 214-216.

Wright, J. G., Rudicel, S. A. L. L. Y., & Feinstein, A. R. (1994). Ask patients what they want. Evaluation of individual complaints before total hip replacement. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British Volume, 76(2), 229-234.

Rathod PA, Deshmuka AJ, Ranawat AS, Rodriguez JA. Sexual function improves significantly following total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective study. Program and abstracts of the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; March 19-23, 2013; Chicago, Illinois. Poster P023.

Today we get to hear from Sherine Aubert, PT, DPT, PRPC who just earned her certification! Sherine was kind enough to share her story about discovering pelvic rehabilitation.

Tell us a bit about your clinical practice

Tell us a bit about your clinical practice

Men and women across the life span with urogynecological, colorectal, orthopedic, as well as pre and post-surgical cases including sexual reassignment surgeries make up the majority of the population I treat. Most patients are working towards improving their bedroom and bathroom issues including prolapse, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, incontinence, pelvic pain, coccydynia, voiding dysfunctions, interstitial cystitis, vaginismus and dyspareunia. Educating and setting male patients up with pre surgical prostatectomy pelvic floor muscle strengthening programs and as well as improving outcomes of patients who have undergone sexual reassignment surgeries.

How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

I have always had such respect and fascination with the pelvic floor muscles. They are underestimated and overlooked in many physical therapy settings and I feel passionate about changing this! I have made it my goal to educate and empower individuals while making a comfortable environment to ask questions to further understand their anatomy, function and optimize their health.

What/who inspired you to become involved in pelvic rehabilitation?

I have been very lucky to have many wonderful influences in my academic and professional career. The two pelvic floor “geniuses” who have always had time to discuss new treatments, brainstorm, and optimize my skill set would be Dr. Chris Eddow PT, DPT, OCS, WCS, CHT and Dr. Jamie Taylor PT, DPT. Thanks for always pushing me to the next level ladies, I look forward to advancing the pelvic floor world with you gals!

What do you find is the most useful resource for your practice?

During every initial evaluation I use a pelvic model to show all the pelvic floor muscles, organs and connective tissue with an overview of anatomy and function. I find patients are very appreciative of the explanation and find extreme value in understanding their own anatomy. Every time I show the model, I feel like I am sharing the world’s best secret about their bodies!

What motivated you to earn PRPC?

I appreciated the fact that "PRPC" included men and women's knowledge base.

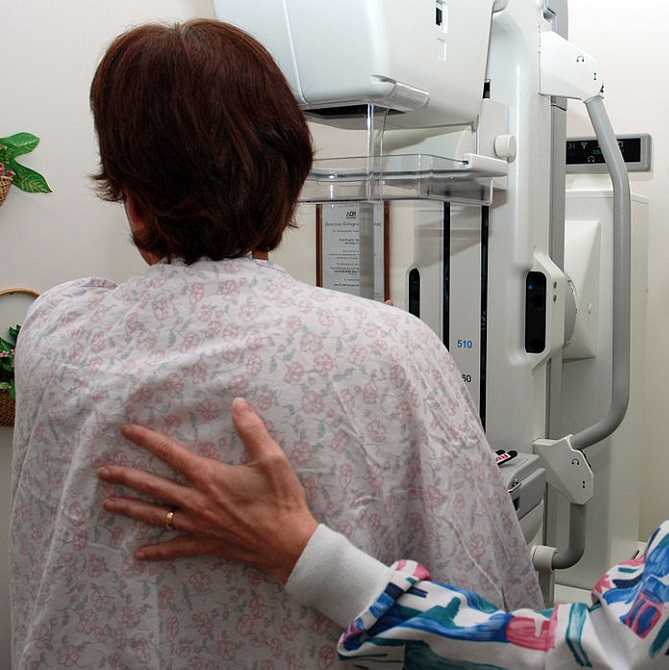

My first experience treating a patient with shoulder pain and limitations post-mastectomy just happened to be a local doctor’s sister. Luckily, I did not know this until a few sessions into her therapy. Ultimately, even more than normal, this patient’s outcome was a make or break situation for a future referral source. Her incredible spirit and optimism made the prognosis an inevitably positive one. Whether or not I had manual therapy training was a moot point, according to current research; however, from my perspective, I would not have been as competent in treating her without it.

In June 2015, De Groef et al. performed a review of literature to investigate the efficacy of physical therapy for upper extremity impairments after surgical intervention for breast cancer. Eighteen randomized controlled studies were chosen for review regarding the efficacy of passive mobilization, myofascial therapy, manual stretching, and/or exercise therapy after breast cancer treatment. In the studies reviewed, physical therapy began at least 6 weeks post-surgical intervention. Combining general exercise with stretching was confirmed effective on range of motion (ROM) by 2 studies. One study showed the effect of passive mobilization with massage was null for pain or impaired ROM. No study showed any effect of myofascial therapy, one poor quality study supported the use of passive mobilization alone, and one study showed no effect of stretching alone. Active exercises were found more effective than no therapy or simply education in five studies. Early intervention was found to be beneficial for shoulder ROM in 3 studies, but 4 other studies supported delayed exercise to promote wound healing longer. Ultimately, pain and impaired shoulder ROM after operative treatment for breast cancer have been treated effectively by a multifactorial approach of stretching and active exercise. The efficacy of passive mobilization, stretching, and myofascial therapy needs to be investigated with higher quality research in the future.

In June 2015, De Groef et al. performed a review of literature to investigate the efficacy of physical therapy for upper extremity impairments after surgical intervention for breast cancer. Eighteen randomized controlled studies were chosen for review regarding the efficacy of passive mobilization, myofascial therapy, manual stretching, and/or exercise therapy after breast cancer treatment. In the studies reviewed, physical therapy began at least 6 weeks post-surgical intervention. Combining general exercise with stretching was confirmed effective on range of motion (ROM) by 2 studies. One study showed the effect of passive mobilization with massage was null for pain or impaired ROM. No study showed any effect of myofascial therapy, one poor quality study supported the use of passive mobilization alone, and one study showed no effect of stretching alone. Active exercises were found more effective than no therapy or simply education in five studies. Early intervention was found to be beneficial for shoulder ROM in 3 studies, but 4 other studies supported delayed exercise to promote wound healing longer. Ultimately, pain and impaired shoulder ROM after operative treatment for breast cancer have been treated effectively by a multifactorial approach of stretching and active exercise. The efficacy of passive mobilization, stretching, and myofascial therapy needs to be investigated with higher quality research in the future.

Another review of literature in 2010 by McNeely et al. used 24 studies to analyze the effectiveness of exercise intervention for upper extremity impairments after breast cancer surgical intervention. Ten of the studies focused on early versus late intervention, and all supported the earlier implementation of post-surgical exercises for ROM; however, wound drain volume and duration were increased in the subjects engaged in earlier exercises. Fourteen studies showed structured exercise intervention improved shoulder ROM significantly in the post-op period, and a 6-month follow up continued to show improved upper extremity function. No lymphedema risk was noted in any of the studies.

As with many areas of physical therapy, better research is needed to support what we do. We often treat with success in the clinic despite lack of strength in the evidence-based realm. After implementing glenohumeral and scapulothoracic mobilizations, soft tissue work in the posterior cervical and scapular muscles (avoiding lymph nodes), stretching, progressive resisted strengthening, and a home program, my patient regained full range of motion and function of the affected shoulder after her mastectomy. In retrospect, I should have written up a case study on this patient to contribute to our profession. At least after my patient was discharged, the clinic where I worked received a healthy supply of future referrals from her sister because of the positive results achieved with therapy.

If you are interested in learning evaluation and treatment techniques which can benefit breast oncology patients, consider a Herman & Wallace Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient course in 2016.

De Groef A, Van Kampen M, Dieltjens E, Christiaens MR, Neven P, Geraerts I, Devoogdt N. (2015). Effectiveness of postoperative physical therapy for upper-limb impairments after breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 96(6):1140-53. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.01.006. Epub 2015 Jan 13.

McNeely ML, Campbell K, Ospina M, Rowe BH, Dabbs K, Klassen TP, Mackey J, Courneya K. (2010). Exercise interventions for upper-limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. The Cochrane Database System of Reviews. (6):CD005211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005211.pub2.

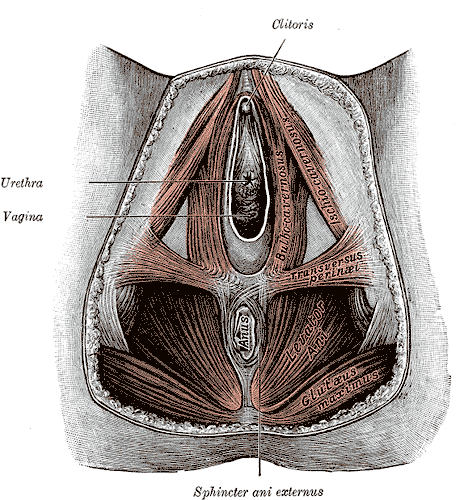

Episiotomy is defined as an incision in the perineum and vagina to allow for sufficient clearance during birth. The concept of episiotomy with vaginal birth has been used since the mid to late 1700’s and started to become more popular in the United States in the early 1900’s. Episiotomy was routinely used and very common in approximately 25% of all vaginal births in the United States in 2004. However, in 2006, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended against use of routine episiotomies due to the increased risk of perineal laceration injuries, incontinence, and pelvic pain. With this being said, there is much debate about their use and if there is any need at all to complete episiotomy with vaginal birth.

What are the negative outcomes of episiotomy?

What are the negative outcomes of episiotomy?

The primary risks are severe perineal laceration injuries, bowel or bladder incontinence, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and pelvic floor laxity. Use of a midline episiotomy and use of forceps are associated with severe perineal laceration injury. However, mediolateral episiotomies have been indicated as an independent risk factor for 3rd and 4th degree perineal tears. If episiotomy is used, research indicates that a correctly angled (60 degrees from midline) mediolateral incision is preferred to protect from tearing into the external anal sphincter, and potentially increasing likelihood for anal incontinence.

What are the indications for episiotomy, if any?

This remains controversial. Some argue that episiotomies may be necessary to facilitate difficult child birth situations or to avoid severe maternal lacerations. Examples of when episiotomy may be used could include shoulder dystocia (a dangerous childbirth emergency where the head is delivered but the anterior shoulder is unable to pass by the pubic symphysis and can result in fetal demise.), rigid perineum, prolonged second stage of delivery with non reassuring fetal heart rate, and instrumented delivery.

On the other side of the fence, many advocate never using an episiotomy due to the previously stated outcomes leading to perineal and pelvic floor morbidity. In a recent cohort study in 2015 by Amorim et al., the question of “is it possible to never perform episiotomy with vaginal birth?” was explored. 400 women who had vaginal deliveries were assessed following birth for perineum condition and care satisfaction. During the birth there was a strict no episiotomy policy and Valsalva, direct pushing, and fundal pressure were avoided, and perineal massage and warm compresses were used. In this study there were no women who sustained 3rd or 4th degree perineal tears and 56% of the women had completely intact perineum. 96% of the women in the study responded that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their care. The authors concluded that it is possible to reach a rate of no episiotomies needed, which could result in reduced need for suturing, decreased severe perineal lacerations, and a high frequency of intact perineum’s following vaginal delivery.

Are episiotomies actually being performed less routinely since the 2006 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendation?

Yes, a recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association by Friedman, it showed that the routine use of episiotomy with vaginal birth has declined over time likely reflecting an adoption of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations. This is ideal, as it remains well established that episiotomy should not be used routinely. However, indications for episiotomy use remain to be established. Currently, physicians use clinical judgement to decide if episiotomy is indicated in specific fetal-maternal situations. If one does receive an episiotomy then a mediolateral incision is preferred. The World Health Organization’s stance is that an acceptable global rate for the use of episiotomy is 10% or less of vaginal births. So the question still remains, (and of course more research is needed) to episiotomy or not to episiotomy?

Amorim, M. M., Franca-Neto, A. H., Leal, N. V., Melo, F. O., Maia, S. B., & Alves, J. N. (2014). Is It Possible to Never Perform Episiotomy During Vaginal Delivery?. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 123, 38S.

Friedman, A. M., Ananth, C. V., Prendergast, E., D’Alton, M. E., & Wright, J. D. (2015). Variation in and Factors Associated With Use of Episiotomy. JAMA, 313(2), 197-199.

Levine, E. M., Bannon, K., Fernandez, C. M., & Locher, S. (2015). Impact of Episiotomy at Vaginal Delivery. J Preg Child Health, 2(181), 2.

Melo, I., Katz, L., Coutinho, I., & Amorim, M. M. (2014). Selective episiotomy vs. implementation of a non episiotomy protocol: a randomized clinical trial. Reproductive health, 11(1), 66.

This week we are proud to feature Christy Ciesla, PT, DPT, PRPC! She just earned her Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification, and was kind enough to share some of her thoughts with the Pelvic Rehab Report. You can read the interview below. Congratulations to Christy and all the other PRPC practitioners!

This week we are proud to feature Christy Ciesla, PT, DPT, PRPC! She just earned her Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification, and was kind enough to share some of her thoughts with the Pelvic Rehab Report. You can read the interview below. Congratulations to Christy and all the other PRPC practitioners!

Tell us about your clinical practice:

I am currently coordinating a Women and Men’s Health program at the Miriam Hospital (The Men’s Health Center and The Women’s Medicine Collaborative) in Rhode Island. We are fortunate to be a team of 5 skilled pelvic therapists and to work with the some of the best physicians and surgeons in New England. We work with so many different patients. I am currently most excited about our involvement in a tremendous Cancer Survivorship Program offered here at the Women’s Medicine Collaborative.

How did you get involved in Pelvic Rehab?

I have always been actively involved in women’s issues, even as a college student, helping with programming for the Women’s Resource Center on campus. After I had my first son in 2003, I became very interested in working with pregnant and postpartum women, and the pelvic rehab involvement took off from there. I was sent my first male patient in 2008, and found that I enjoyed working with men just as much as working with women in this area.

What/who inspired you to become involved in pelvic rehabilitation?

I went to Elizabeth Noble’s OB/Gyn and Prenatal Exercise Courses in 2004. During the course, we talked quite a bit about birth and the pelvic floor. I left there fascinated with the field, and took my first pelvic floor course a couple of years later.

What patient population do you find most rewarding in treating and why?

I love treating all of my patients, but perhaps the most rewarding feeling is when I can help a cancer survivor SURVIVE their cancer. All too often, when the treatment ends, the patient is left to feel alone with all of the effects of chemo, radiation and surgical trauma. They have incontinence, pelvic pain, and sexual dysfunction, and feel lost. Being able to offer a light in the darkness to these people is the greatest gift that pelvic rehabilitation has given me.

If you could get a message out to physical therapists about pelvic rehabilitation what would it be?

You will never have more of a rewarding experience than you will when you help your patients pee, poop and have sex without dysfunction. I mean, really….what else is there to life?!

What has been your favorite Herman & Wallace Course and why?

PF 1 has still got to be my favorite. It was the most packed with great info, Holly was my instructor, and I was first introduced to the magical world of pelvic rehabilitation. I will never forget that experience.

What lesson have you learned from a Herman & Wallace instructor that has stayed with you?

One of the things that has been consistently conveyed in all of my courses with H&W is the importance of caring for, respecting, and honoring our patients for having the bravery to address these sensitive issues, and to share them with us. The coursework prepared me with the knowledge I needed to help my patients, but the amazing instructors also helped me be a better provider in other ways.

What motivated you to earn PRPC?

So far, I have taken 7 Herman and Wallace courses (8 including the PF 1 course that Holly did privately for my facility and I was able to assist with). It just seemed right to be certified through this wonderful institute. It is what I do every day, all day, and I felt that I needed these credentials to go further with my career in this field.

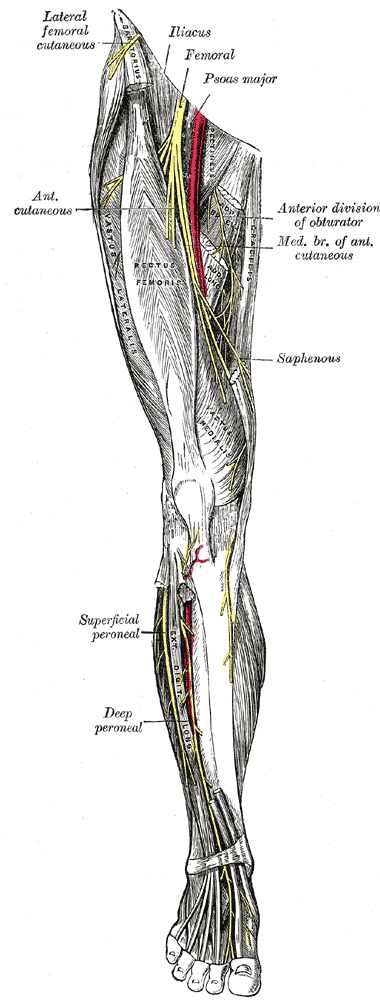

Postpartum lower extremity nerve injuries is an important topic that we have previously discussed on the blog. A review article(O'Neal 2015) published in the International Anesthesia Research Society journal discusses maternal neurological complications following childbirth. This article, designed to help anesthesiologists identify the symptoms of a neuropathy, discusses diagnosis, management, and treatment. With the incidence of obstetric neuropathy in the postpartum period estimated at 1%, most of the nerve dysfunction is related to compression injuries. Symptoms may include, but are not limited to, lower extremity pain, weakness, numbness, or bowel and bladder dysfunction. Neuraxial anesthesia can also occur, with issues such as epidural hematoma or an epidural abscess. Risk factors are described in the article as having a prolonged second stage of labor, instrumented delivery, being of short stature and nulliparity (delivering for the first time.)

Clinical pearls listed in the article include the following information that may be helpful in understanding a patient’s condition:

Clinical pearls listed in the article include the following information that may be helpful in understanding a patient’s condition:

- intramedullary spinal cord syndromes (inside the spinal cord) are usually painless, whereas the peripheral nerve syndromes (involving the spinal nerve roots, plexus, and single nerves) usually cause pain

- bowel and bladder dysfunction often occurs early in the case of conus medullaris and late in the event of cauda equina syndrome

- cauda equina syndrome often causes polyradicular pain, leg weakness, numbness, and deep tendon reflex changes and involves multiple roots

- conus medullaris syndrome is not painful and causes saddle anesthesia and lack of significant sensory and motor symptoms in the lower extremities

In relation to prevention of neuropathies, the authors suggest that women who have diabetes or who have a preexisting neuropathy should be given extra attention. This may include protective padding during labor and delivery as well as frequent repositioning. Pelvic rehabilitation providers are a key player in the arena of birthing. Caring for women and educating them about peripartum issues is critical to helping women both prevent and heal from challenges encountered in relation to pregnancy and childbirth. If you would like to learn more about the topic of peripartum nerve dysfunctions, as well as many other special topics, please join us for the continuing education course Care of the Postpartum Patient. Your next opportunity to take this course will be in Seattle next March!

O’Neal, M. A., Chang, L. Y., & Salajegheh, M. K. (2015). Postpartum Spinal Cord, Root, Plexus and Peripheral Nerve Injuries Involving the Lower Extremities: A Practical Approach. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 120(1), 141-148.

If you celebrated the Thanksgiving holiday by enjoying food with family or friends, you may be lamenting the sheer amount of food you ate, or the calories that you took in. Did you know that chewing your food well can not only affect how much you eat, but also how much nutrition you derive from food? In a meta-analysis by Miquel-Kergoat et al. on the affects of chewing on several variables, researchers found that chewing affects hunger, caloric intake, and even has an impact on gut hormones. Ten papers that covered thirteen trials were included in the meta-analysis. From these trials, the following data are reported:

- 10 of 16 studies found that prolonged chewing reduced a person’s food intake

- chewing decreases self-reported hunger

- chewing decreases amount of food intake

- increasing the number of chews per bite increases gut hormone release

- chewing promotes feeling full

Research about eating behavior theories are highlighted in this paper, and include a discussion of the variety of factors, both internal and external, that control eating. Chewing is described as providing “…motor feedback to the brain related to mechanical effort…” that may influence how full a person feels when eating foods that are chewed. On the contrary, foods and beverages that do not require much chewing may be associated with overconsumption due to the lack of chewing required. (This makes sense when considering sugar-laden, high-calorie beverages.) Additionally, chewing food mixes important digestive enzymes and breaks down the food properly in the mouth, making the process of digestion further along the digestive tract more efficient. Another study by Cassady et al. which assessed differences in hunger when chewing almonds 25 versus 40 times reported that increased chewing led to decreased hunger and increased satiety when compared to chewing only 25 times.

The theory presented, yet not concluded, in this paper is that chewing may affect gut hormones and thereby decrease self-reported hunger and decrease food intake. For various reasons, including deriving more nutrition from our food, avoiding overconsumption, or making the process of digestion more efficient, focusing more on the act of chewing our food can have beneficial affects. To learn more about health and nutrition, attend the Institute’s course Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist (link: https://hermanwallace.com/continuing-education-courses/nutrition-perspectives-for-the-pelvic-rehab-therapist). This continuing education course was written and instructed by Meghan Pribyl, who is not only a physical therapist who practices in pelvic rehabilitation and orthopedics, but who also has a degree in nutrition. Her training and qualifications allow her to share important information that integrates the fields of rehabilitation and nutrition. Your next opportunity to take this course is in March in Kansas City.

Cassady, B. A., Hollis, J. H., Fulford, A. D., Considine, R. V., & Mattes, R. D. (2009). Mastication of almonds: effects of lipid bioaccessibility, appetite, and hormone response. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 89(3), 794-800. Miquel-Kergoat, S., Azais-Braesco, V., Burton-Freeman, B., & Hetherington, M. M. (2015). Effects of chewing on appetite, food intake and gut hormones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiology & behavior, 151, 88-96.

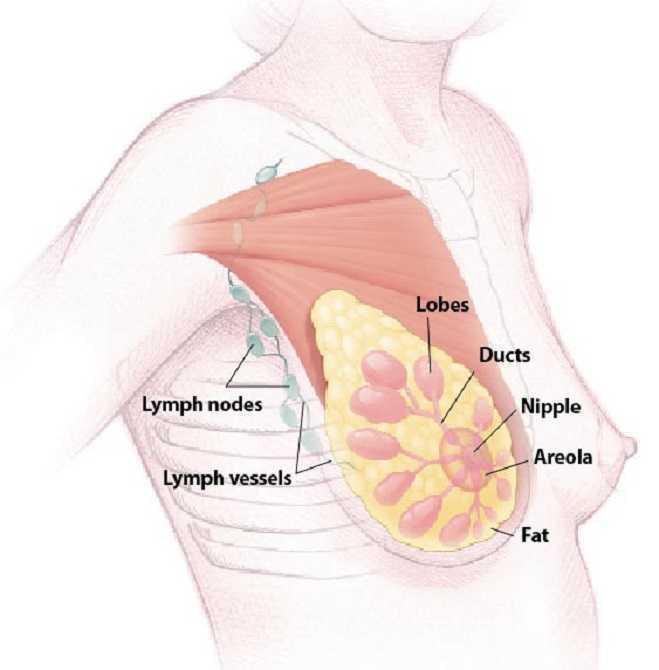

Milk duct blockage is a common condition in breast feeding mother’s that can cause a multitude of problems including painful breasts, mastitis, breast abscess, decreased milk supply, breast feeding cessation, and poor confidence with decreased quality of life. A recent study in 2015 in The Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1, showed that physical therapy (PT) maybe a helpful treatment for the lactating mother experiencing milk duct blockage when conservative measures have failed. Common conservative measures typically recommended are self-massage, heat, and regular feedings. The World Health Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and Academy of Breast Feeding Medicine, all recommend breast feeding as the primary source for nutrition for infants. There are many benefits to both the mother, and the infant, when breast feeding is used as the primary source for nutrition in infants. Having blocked milk ducts make it difficult and painful to breast feed and can lead to poor confidence for the mother and a frustrated baby as the milk supply could be reduced or inadequate. The primary health concern for blocked milk ducts is mastitis. Mastitis is defined as an infection of breast tissue leading to pain, redness, swelling, and warmth, possibly fever and chills and can lead to early cessation of breast feeding.

A blocked milk duct is not a typical referral to PT, however, this study outlined a protocol used for 30 patients with one or more blocked milk ducts that were referred to PT by a qualified lactation consultant. This study was a prospective pre/posttest cohort study. As an outcome measure, this study utilized a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for 3 descriptive areas: pain, difficulty breast feeding, and confidence in independently nursing before and after treatment. The treatment protocol included moist heat, thermal ultrasound, specific manual therapy techniques, and patient education for treatment and prevention of the blockage(s). The thermal ultrasound and moist heating provided the recommend amount of heat to relax tissue around the blockage. Ultrasound also provided a mechanical effect that assists in the breaking up of the clog and increased pain threshold for the patient to improve tolerance to the manual clearing techniques. Next, the specific manual therapy was provided to directly unclog the blockage(s), and lastly the education provided was to help the patient identify and clear future blockages to prevent recurrence. 22 of the 30 patients were seen for 1-2 visits, 6 were seen for 3-4 visits, and none of the mother’s condition progressed to infective mastitis or developed breast abscess’s.

A blocked milk duct is not a typical referral to PT, however, this study outlined a protocol used for 30 patients with one or more blocked milk ducts that were referred to PT by a qualified lactation consultant. This study was a prospective pre/posttest cohort study. As an outcome measure, this study utilized a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for 3 descriptive areas: pain, difficulty breast feeding, and confidence in independently nursing before and after treatment. The treatment protocol included moist heat, thermal ultrasound, specific manual therapy techniques, and patient education for treatment and prevention of the blockage(s). The thermal ultrasound and moist heating provided the recommend amount of heat to relax tissue around the blockage. Ultrasound also provided a mechanical effect that assists in the breaking up of the clog and increased pain threshold for the patient to improve tolerance to the manual clearing techniques. Next, the specific manual therapy was provided to directly unclog the blockage(s), and lastly the education provided was to help the patient identify and clear future blockages to prevent recurrence. 22 of the 30 patients were seen for 1-2 visits, 6 were seen for 3-4 visits, and none of the mother’s condition progressed to infective mastitis or developed breast abscess’s.

The results of the study showed the protocol used was helpful to ease pain, reduce difficulty with breast feeding, and improve confidence with independent breast feeding for lactating women that participated in the study. Although treatment of blocked milk ducts in lactating mothers is not a common PT referral, this study shows that PT may be one more helpful treatment for a patient experiencing this problem that is not responding to traditional conservative treatment. Since breast feeding is important to both mother and infant and is the primary recommended source for infant nutrition, it is important that a lactating mother receives quick, effective treatment for blocked milk ducts to prevent onset of mastitis and breast abscess that lead to early cessation of breast feeding. The cited study recommends that women who suspect a blocked milk duct or are having problems with breast feeding always seek care from a certified lactation consultant first, and that PT may be a referral that is made.

Cooper, B. B., & Kowalsky, D. S. (2015). Physical Therapy Intervention for Treatment of Blocked Milk Ducts in Lactating Women. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 39(3), 115-126.

The day my son was born, my daughter had not defecated for 5 days, and her pain was getting pretty intense. My husband and his mom took her to Seattle Children’s Hospital for help, and they suggested using Miralax and sent them away. When they got back to my hospital room, my daughter was straining so hard it looked like she was about to give birth! Being physical therapists, my husband and I massaged her little muscles and told her to take deep breaths, and eventually she did the deed, yet not without a heart-breaking struggle. Little did I know then there is actually research to back up our emergency, instinctual technique.

Zivkovic et al (2012) performed a study regarding the use of diaphragmatic breathing exercises and retraining of the pelvic floor in children with dysfunctional voiding. They defined dysfunctional voiding as urinary incontinence, straining, weakened stream, feeling the bladder has not emptied, and increased EMG activity during the discharge of urine. Although this study focuses primarily on urinary issues, it also includes constipation in the treatment and outcomes. Forty-three patients between the ages of 5 and 13 with no neurological disorders were included in the study. The subjects underwent standard urotherapy (education on normal voiding habits, appropriate fluid intake, keeping a voiding chart, and posture while voiding) in addition to pelvic floor muscle retraining and diaphragmatic breathing exercises. The results showed 100% of patients were cured of their constipation, 83% were cured of urinary incontinence, and 66% were cured of nocturnal enuresis.

Zivkovic et al (2012) performed a study regarding the use of diaphragmatic breathing exercises and retraining of the pelvic floor in children with dysfunctional voiding. They defined dysfunctional voiding as urinary incontinence, straining, weakened stream, feeling the bladder has not emptied, and increased EMG activity during the discharge of urine. Although this study focuses primarily on urinary issues, it also includes constipation in the treatment and outcomes. Forty-three patients between the ages of 5 and 13 with no neurological disorders were included in the study. The subjects underwent standard urotherapy (education on normal voiding habits, appropriate fluid intake, keeping a voiding chart, and posture while voiding) in addition to pelvic floor muscle retraining and diaphragmatic breathing exercises. The results showed 100% of patients were cured of their constipation, 83% were cured of urinary incontinence, and 66% were cured of nocturnal enuresis.

More recently, Farahmand et al (2015) researched the effect of pelvic floor muscle exercise for functional constipation in the pediatric population. Stool withholding and delayed colonic transit are most often the causes for children having difficulty with bowel movements. Behavioral modifications combined with laxatives still left 30% of children symptomatic. Forty children between the ages of 4 and 18 performed pelvic floor muscle exercise sessions at home, two times per day for 8 weeks. The children walked for 5 minutes in a semi-sitting (squatting) position while being supervised by parents. The patients increased the exercise duration 5 minutes per week for the first two weeks and stayed the same over the next six weeks. The results showed 90% of patients reported overall improvement of symptoms. Defecation frequency, fecal consistency and decrease in fecal diameter were all found to be significantly improved. Although not statistically significant, the number of patients with stool withholding, fecal impaction, fecal incontinence, and painful defecation decreased as well.

Parents may not be as aware of their children’s voiding habits once they are cleared from diaper duty after successful potty training occurs. To help prevent issues, keep the basics covered, such as making sure children are exercising regularly or being active, drinking plenty of fluids, and eating a diet that includes plenty of fiber. My daughter was only 26 months old when her constipation became a problem, so the stool softener was ultimately the way to go at that time, and everything worked out naturally over the next year. If she were still experiencing functional constipation, I would be delighted to know teaching her pelvic floor exercises (relaxation being the key aspect) and diaphragmatic breathing could be effective for keeping my crazy little girl regular in at least that area of her life!

Zivkovic V, Lazovic M, Vlajkovic M, Slavkovic A, Dimitrijevic L, Stankovic I, Vacic N. (2012). Diaphragmatic breathing exercises and pelvic floor retraining in children with dysfunctional voiding. European J ournal of Physical Rehabilitation Medicine. 48(3):413-21. Epub 2012 Jun 5.

Farahmand, F., Abedi, A., Esmaeili-dooki, M. R., Jalilian, R., & Tabari, S. M. (2015). Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercise for Paediatric Functional Constipation.Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research : JCDR, 9(6), SC16–SC17. http://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2015/12726.6036

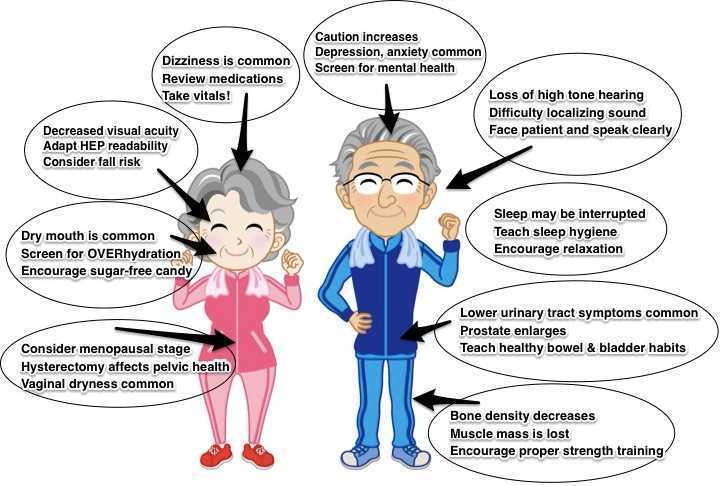

The 2012 guidelines for the treatment of overactive bladder in adults (updated in 2014) recommends as first line treatment behavioral therapies. These therapies include bladder training, bladder control strategies, pelvic floor muscle training, fluid management- all tools that can be learned in the Institute’s Pelvic Floor Level 1 course. These behavioral therapies may also be combined with medication prescription, according to the guideline.

When medications are prescribed for overactive bladder, oral anti-muscarinics or oral B3-adrenergic agonists may be prescribed. Although these drugs may help to relax smooth muscles in the bladder wall, the side effects are often strong enough to make the medication difficult to tolerate. Side effects of constipation and dry mouth can occur, and when they do, patients should communicate that to their physician so that the medication dosage or class can be evaluated and modified if possible. We know that patients who have constipation tend to have more bladder dysfunction, so patients can get stuck in a vicious cycle.

When medications are prescribed for overactive bladder, oral anti-muscarinics or oral B3-adrenergic agonists may be prescribed. Although these drugs may help to relax smooth muscles in the bladder wall, the side effects are often strong enough to make the medication difficult to tolerate. Side effects of constipation and dry mouth can occur, and when they do, patients should communicate that to their physician so that the medication dosage or class can be evaluated and modified if possible. We know that patients who have constipation tend to have more bladder dysfunction, so patients can get stuck in a vicious cycle.

Although patients and their medications are screened at their prescriber’s office and often at the pharmacy, it is important to remember that therapists are an important part of this safety mechanism. Patients may not be candidates for anti-muscarinics if they have narrow angle glaucoma, impaired gastric emptying, or a history of urinary retention. When patients are taking other medications with anticholinergic properties, or are considered frail, adverse drug reactions can also occur. Our geriatric patients may have some additional considerations, not just in medication screening, but also in evaluation and intervention. If you are interested in learning more about pelvic rehabilitation for those in the geriatric population, check out our new continuing education course, Geriatric Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation with Heather S. Rader, PT, DPT, BCB-PMD. The next opportunity to take the class is January 16-17, 2016 in Tampa.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com/