Advancing Understanding of Nutrition’s Role in…..Well….Everything

Gratitude filled my heart after being able to take part in the pre-conference course sponsored by the APTA Orthopedic Section’s Pain Management Special Interest Group this past February. For two days, participants heard from leaders in the field of progressive pain management with integrative topics including neuroscience, cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, sleep, yoga, and mindfulness to name a few. It’s exciting to witness and participate in the evolution of integrative thinking in physical therapy. When it was my turn to deliver the presentation, I had prepared about nutrition and pain, I could hardly contain my passion. While so much of our pain-related focus is placed on the brain, I realized acutely the stone yet unturned is the involvement of the enteric nervous system (aka the gut) on pain and….well…everything.

Much appreciation is due to those on the forefront of pain sciences for their research, their insight, their tireless work to fill our tool boxes with pain education concepts. Neuroscience has made tremendous leaps and bounds as has corresponding digital media to help explain pain to our patients. One such brilliant 5-minute tool can be found on the Live Active YouTube channel.

What I love about this video is how intelligently (and artistically!) it puts into accessible language some incredibly complex processes. It even mentions lifestyle and nutrition as playing a role in what is commonly referred to as a maladaptive central nervous system.

"Maladaptive central nervous system"

Ok. I’ll admit, I struggle with the implications of this term. However, what doesn’t sit right with me is the concept of chronic or persistent pain being entirely in the brain as though the brain is a static entity. We know the brain to be plastic but often do not identify just how this is so.

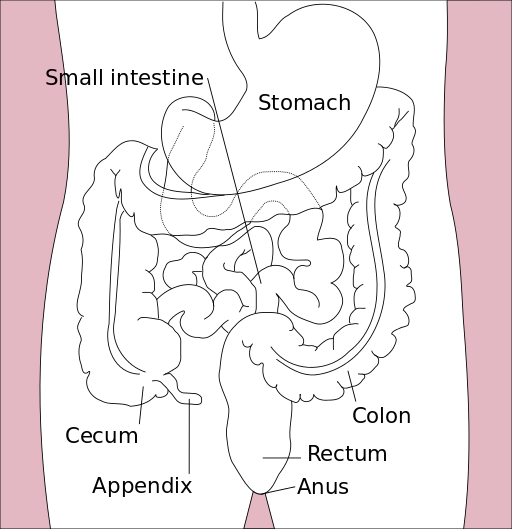

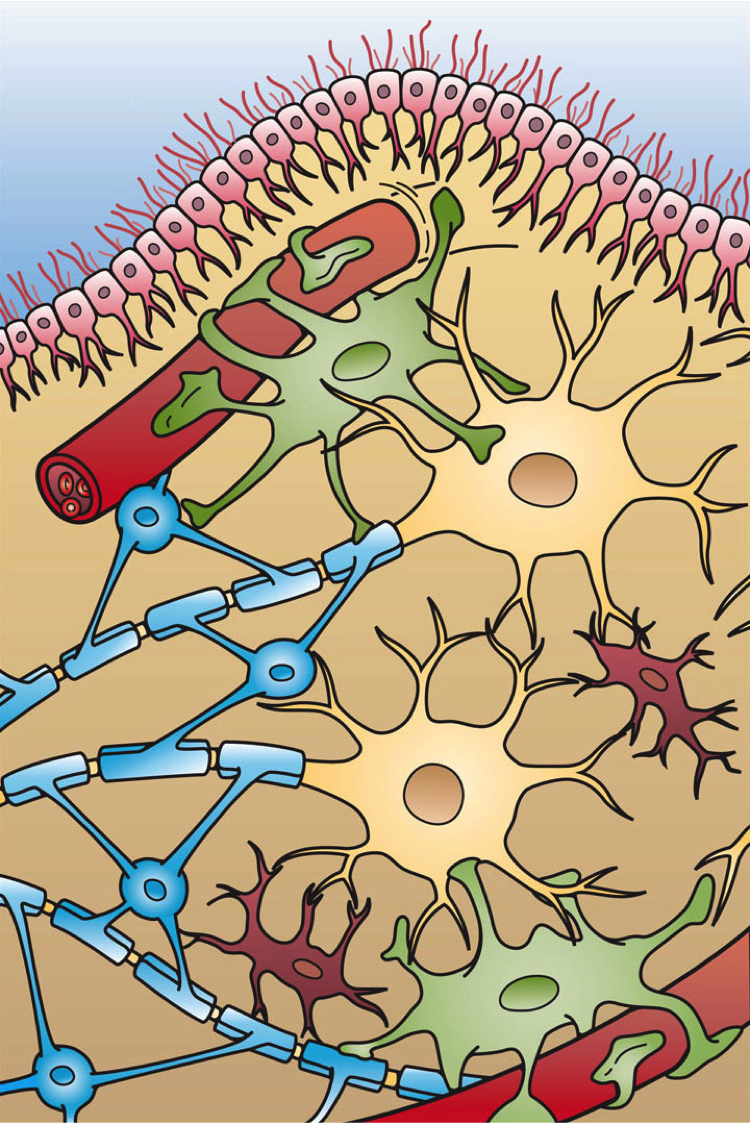

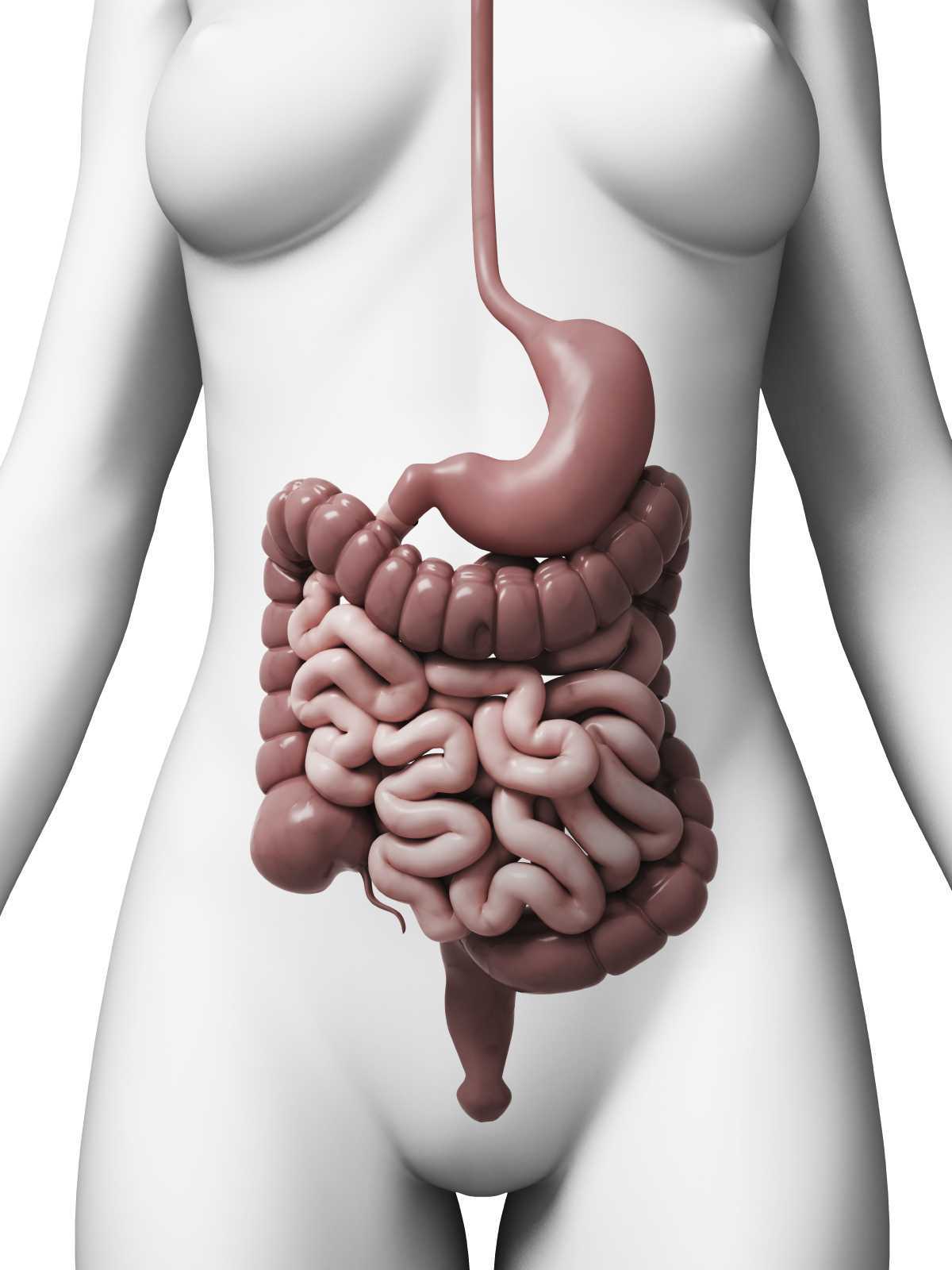

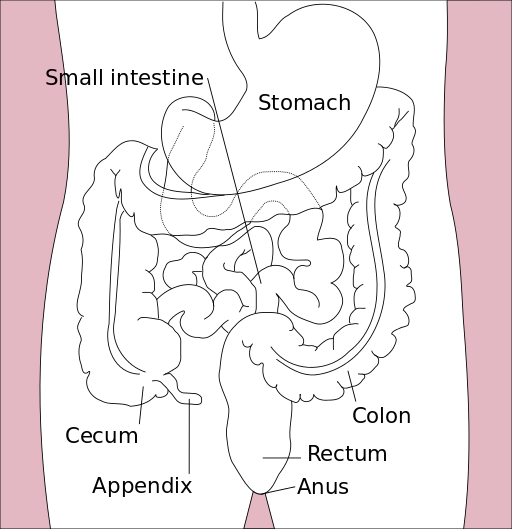

What about the role of our second brain…. the one with 200-600 million neurons that live in that middle part of our body (right next to / inside our pelvis)? Termed the enteric nervous system, this second brain both stores and produces neurotransmittersTurna, et.al., 2016, serves as the scaffolding of interplay between the ENS, SNS, and CNS. This ENS is home to the interface of “bugs, gut, and glial” which are “not only in anatomical proximity, but also influence and regulate each other…interconnected for mutual homeostasis.”Lerner, et.al., 2017 In fact, part of this process then directly impacts the brain. “Healthy brain function and modulation are dependent upon the microbiota’s [gut bugs] activity of the vagus nerve.”Turna, et.al., 2016. Further, “by direct routes or indirectly, through the gut mucosal system and its local immune system, microbial factors, cytokines, and gut hormones find their ways to the brain, thus impacting cognition, emotion, mood, stress resilience, recovery, appetite, metabolic balance, interoception and PAIN.”Lerner, et.al., 2017

What about the role of our second brain…. the one with 200-600 million neurons that live in that middle part of our body (right next to / inside our pelvis)? Termed the enteric nervous system, this second brain both stores and produces neurotransmittersTurna, et.al., 2016, serves as the scaffolding of interplay between the ENS, SNS, and CNS. This ENS is home to the interface of “bugs, gut, and glial” which are “not only in anatomical proximity, but also influence and regulate each other…interconnected for mutual homeostasis.”Lerner, et.al., 2017 In fact, part of this process then directly impacts the brain. “Healthy brain function and modulation are dependent upon the microbiota’s [gut bugs] activity of the vagus nerve.”Turna, et.al., 2016. Further, “by direct routes or indirectly, through the gut mucosal system and its local immune system, microbial factors, cytokines, and gut hormones find their ways to the brain, thus impacting cognition, emotion, mood, stress resilience, recovery, appetite, metabolic balance, interoception and PAIN.”Lerner, et.al., 2017

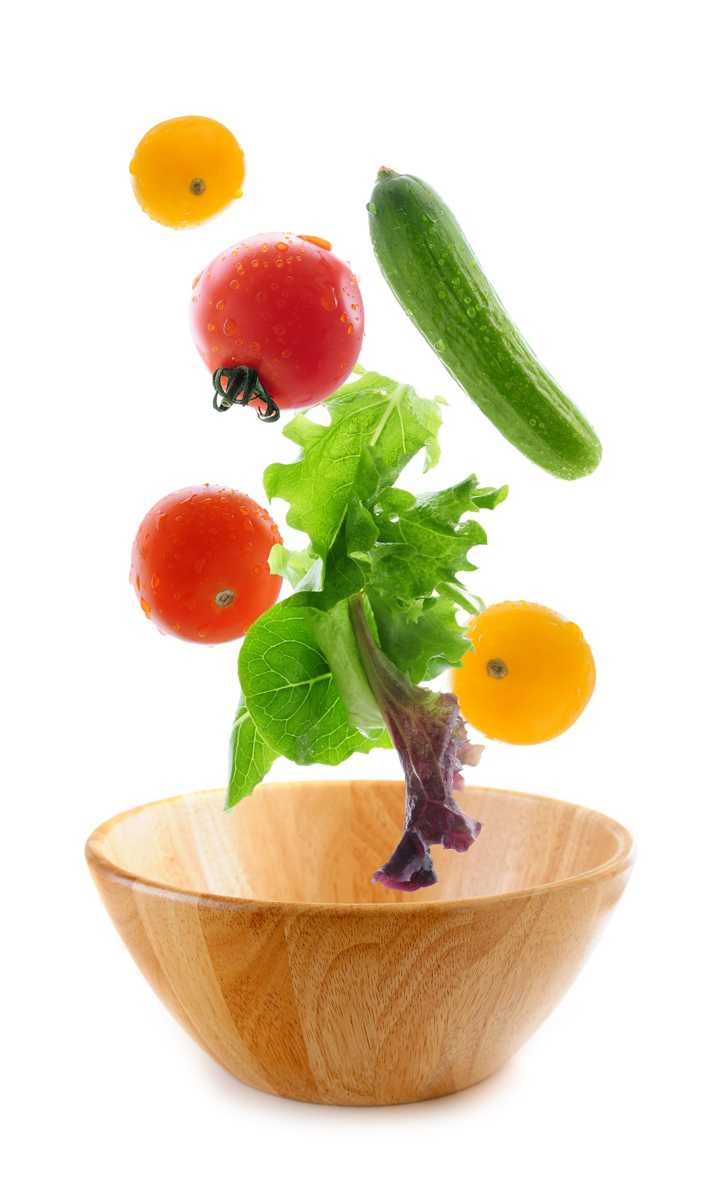

So, by process of logic, it requires little convincing to conclude that the food we eat or fail to eat directly impacts the health or dysfunction of this magnificently orchestrated system. One that directly and profoundly impacts our brain, our body, our being. And it’s a concept that our patients, our clients, ourselves, know in our gut to be true.

And it’s thanks to all the hard work of those who have come before us that we can share in the advancing understanding for the benefit of thousands who need your help, expertise and guidance. Please join me for Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist. The next course will be in Springfield, MO on June 23-24, 2018. Vital and clarifying information awaits you!

Live Active. (2013, Jan) Understanding Pain in less than 5 minutes, and what to do about it! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_3phB93rvI Retrieved March 28, 2018.

Lerner, A., Neidhofer, S., & Matthias, T. (2017). The Gut Microbiome Feelings of the Brain: A Perspective for Non-Microbiologists. Microorganisms, 5(4). doi:10.3390/microorganisms5040066

Turna, J., Grosman Kaplan, K., Anglin, R., & Van Ameringen, M. (2016). "What's Bugging the Gut in Ocd?" a Review of the Gut Microbiome in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Depress Anxiety, 33(3), 171-178. doi:10.1002/da.22454

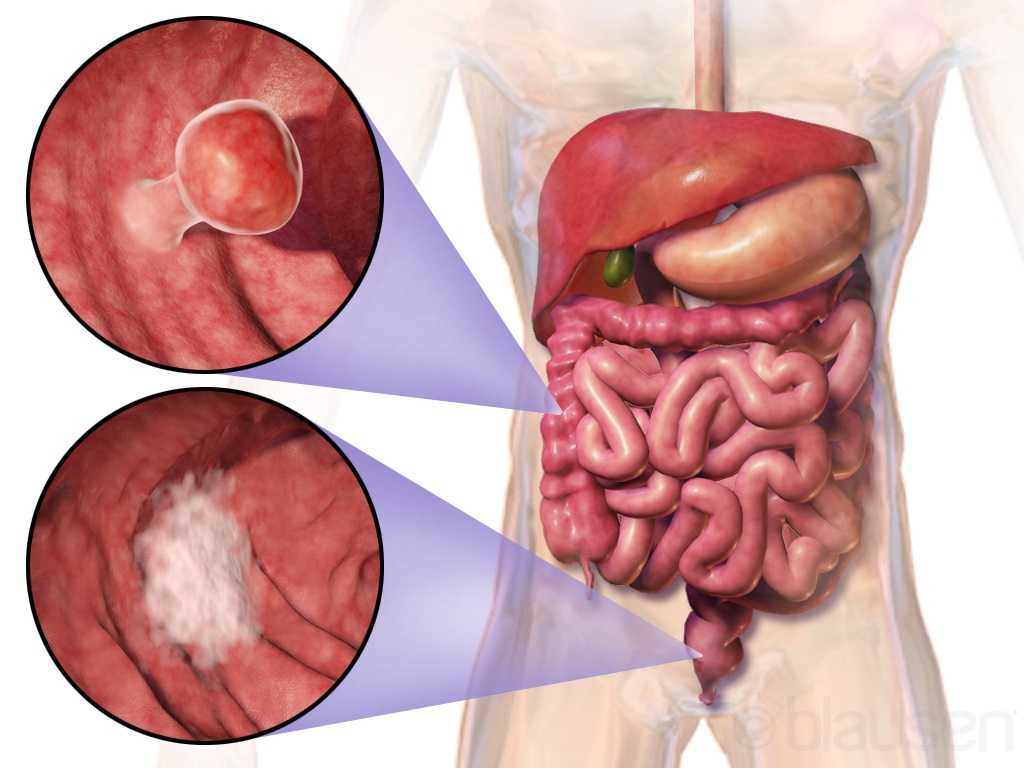

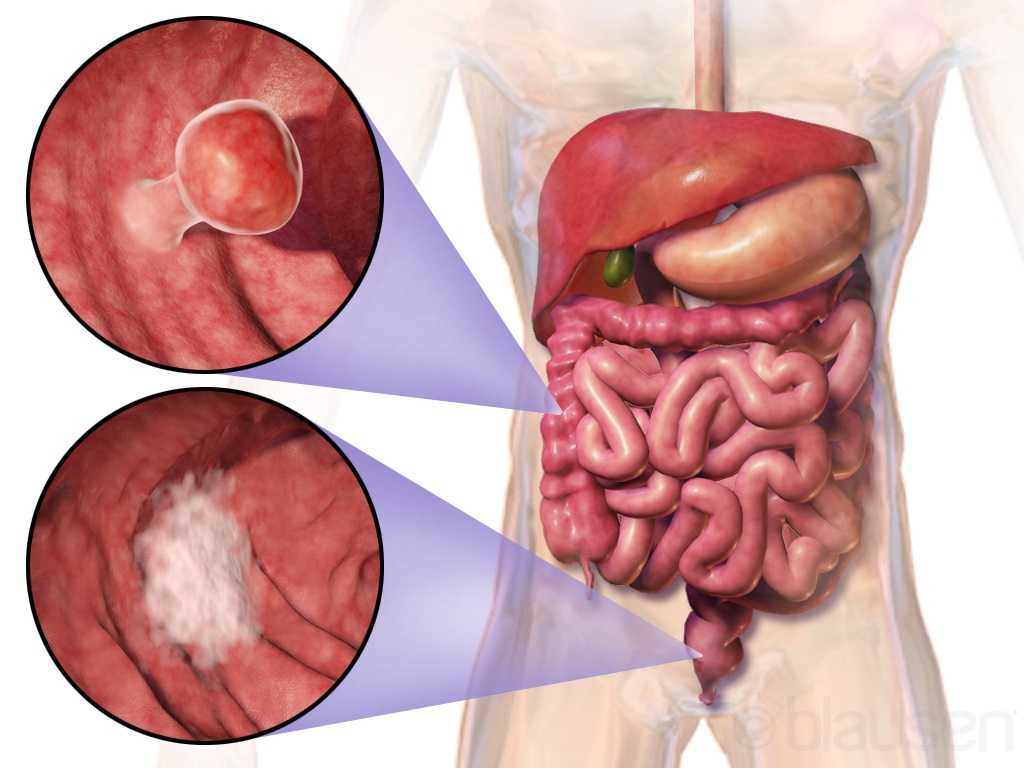

Curing cancer but not addressing life-altering complications can be compared to feeding the homeless on Thanksgiving but turning your back on them the rest of the year. We love hearing positive outcomes of a surgery, but we are not always aware of what happens beyond that. Colorectal cancer is often treated by colectomy, and sometimes the survivor of cancer is left with urological or sexual dysfunction, small bowel obstruction, or pelvic lymphedema.

Panteleimonitis et al., (2017) recognized the prevalence of urological and sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery and compared robotic versus laparoscopic approaches to see how each impacted urogenital function. In this study, 49 males and 29 females underwent laparoscopic surgery, and 35 males and 13 females underwent robotic surgery. Prior to surgery, 36 men and 9 women were sexually active in the first group and 13 men and 4 women were sexually active in the latter group. Focusing on the male results, male urological function (MUF) scores were worse pre-operatively in the robotic group for frequency, nocturia, and urgency compared to the laparoscopic group. Post-operatively, urological function scores improved in all areas except initiation/straining for the robotic group; however, the MUF median scores declined in the laparoscopic group. Regarding male sexual function (MSF) scores for libido, erection, stiffness for penetration and orgasm/ ejaculation, the mean scores worsened in all areas for the laparoscopic group but showed positive outcomes for the robotic group. In spite of limitations of the study, the authors concluded robotic rectal cancer surgery may afford males and females more promising urological and sexual outcomes as robotic.

Panteleimonitis et al., (2017) recognized the prevalence of urological and sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery and compared robotic versus laparoscopic approaches to see how each impacted urogenital function. In this study, 49 males and 29 females underwent laparoscopic surgery, and 35 males and 13 females underwent robotic surgery. Prior to surgery, 36 men and 9 women were sexually active in the first group and 13 men and 4 women were sexually active in the latter group. Focusing on the male results, male urological function (MUF) scores were worse pre-operatively in the robotic group for frequency, nocturia, and urgency compared to the laparoscopic group. Post-operatively, urological function scores improved in all areas except initiation/straining for the robotic group; however, the MUF median scores declined in the laparoscopic group. Regarding male sexual function (MSF) scores for libido, erection, stiffness for penetration and orgasm/ ejaculation, the mean scores worsened in all areas for the laparoscopic group but showed positive outcomes for the robotic group. In spite of limitations of the study, the authors concluded robotic rectal cancer surgery may afford males and females more promising urological and sexual outcomes as robotic.

Husarić et al., (2016) considered the risk factors for adhesive small bowel obstruction (SBO) after colorectal cancer colectomy, as SBO is a common morbidity that causes a decrease in quality of life. They performed a retrospective study of 248 patients who underwent colon cancer surgery, and 13.7% of all the patients had SBO. Thirty (14%) of the 213 males and 9 (12.7%) of the 71 females had SBO; consequently, they found patients being >60 years old was a more significant risk factor than sex regarding occurrence of SBO. The authors concluded a Tumor-Node Metastasis stage of >3 and immediate postoperative complications were found to be the greatest risk factors for SBO.

Vannelli et al., (2013) explored the prevalence of pelvic lymphedema after lymphadenectomy in patients treated surgically for rectal cancer. Five males and 8 females were examined one week before and 12 months after being discharged from the hospital. All 9 of the patients (4 males, 5 females) with extra-peritoneal cancer exhibited lymphedema via MRI, but the 4 (1 male, 3 females) patients with intra-peritoneal cancer had none. The authors concluded pelvic lymphedema can be elusive after rectal surgery, but pelvic disorders persist and patients should be routinely examined for it.

Obviously saving a life is the primary goal when it comes to cancer. But just like caring for the destitute for one day doesn’t cure a lifetime of hunger, ignoring the negative post-surgical sequelae of a colectomy prevents a cancer survivor from living a healthy life. Herman & Wallace offers two pelvic floor oncology courses, “Oncology and the Male Pelvic Floor” and "Oncology and the Female Pelvic Floor" , which address how pelvic cancers affect the quality of life of our patients and how practitioners can make a positive impact.

Panteleimonitis, S., Ahmed, J., Ramachandra, M., Farooq, M., Harper, M., & Parvaiz, A. (2017). Urogenital function in robotic vs laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery: a comparative study. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 32(2), 241–248. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-016-2682-7

Husarić E., Hasukić Š, Hotić N, Halilbašić A, Husarić S, Hasukić I. (2016). Risk factors for post-colectomy adhesive small bowel obstruction. Acta

When I work prn in inpatient rehabilitation, I have access to each patient’s chart and can really focus on the systems review and past medical history, which often gives me ample reasons to ask about pelvic floor dysfunction. So, of course, I do. I have yet to find a gynecological cancer survivor who does not report an ongoing struggle with urinary incontinence. And sadly, they all report that they just deal with it.

Bretschneider et al.2016 researched the presence of pelvic floor disorders in females with presumed gynecological malignancy prior to surgical intervention. Baseline assessments were completed by 152 of the 186 women scheduled for surgery. The rate of urinary incontinence (UI) at baseline was 40.9% for the subjects, all of whom had uterine, ovarian, or cervical cancer. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) was reported by 33.3% of the women, urge incontinence (UI) by 25%, fecal incontinence (FI) by 3.9%, abdominal pain by 47.4%, constipation by 37.7%, and diarrhea by 20.1%. The authors concluded pelvic floor disorders are prevalent among women with suspected gynecologic cancer and should be noted prior to surgery in order to provide more thorough rehabilitation for these women post-operatively.

Bretschneider et al.2016 researched the presence of pelvic floor disorders in females with presumed gynecological malignancy prior to surgical intervention. Baseline assessments were completed by 152 of the 186 women scheduled for surgery. The rate of urinary incontinence (UI) at baseline was 40.9% for the subjects, all of whom had uterine, ovarian, or cervical cancer. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) was reported by 33.3% of the women, urge incontinence (UI) by 25%, fecal incontinence (FI) by 3.9%, abdominal pain by 47.4%, constipation by 37.7%, and diarrhea by 20.1%. The authors concluded pelvic floor disorders are prevalent among women with suspected gynecologic cancer and should be noted prior to surgery in order to provide more thorough rehabilitation for these women post-operatively.

Ramaseshan et al.2017 performed a systematic review of 31 articles to study pelvic floor disorder prevalence among women with gynecologic malignant cancers. Before treatment of cervical cancer, the prevalence of SUI was 24-29% (4-76% post-treatment), UI was 8-18% (4-59% post-treatment), and FI was 6% (2-34% post- treatment). Cervical cancer treatment also caused urinary retention (0.4-39%), fecal urge (3-49%), dyspareunia (12-58%), and vaginal dryness (15-47%). Uterine cancer showed a pre-treatment prevalence of SUI (29-36%), UUI (15-25%), and FI (3%) and post-treatment prevalence of UI (2-44%) and dyspareunia (7-39%). Vulvar cancer survivors had post-treatment prevalence of UI (4-32%), SUI (6-20%), and FI (1-20%). Ovarian cancer survivors had prevalence of SUI (32-42%), UUI (15-39%), prolapse (17%) and sexual dysfunction (62-75%). The authors concluded pelvic floor dysfunction is prevalent among gynecologic cancer survivors and needs to be addressed.

Lindgren, Dunberger, & Enblom2017 explored how gynecological cancer survivors (GCS) relate their incontinence to quality of life, view their physical activity/exercise ability, and perceive pelvic floor muscle training. The authors used a qualitative interview content analysis study with 13 women, age 48–82. Ten women had UI and 3 had FI after treatment (2 had radiation therapy, 5 had surgery, and 6 had surgery as well as radiation therapy). The results showed a reduction in physical and psychological quality of life and sexual activity because of incontinence. Having minimal to no experience or even awareness of pelvic floor training, 9 out of the 10 women were willing to spend 7 hours a week to improve their incontinence. Practical and emotional coping strategies also helped these women, and they all declared they had the cancer treatments without being informed of the risk of incontinence, which impacted their attitude and means of handling the situation.

Research shows incontinence is a common occurrence after gynecological cancer treatment. It impacts quality of life after surviving a serious illness, and many women do not know pelvic floor therapy can improve their situation. Oncology and the Female Pelvic Floor is an ideal course for practitioners to take to help increase their knowledge on how to educate and treat this population.

Bretschneider, C. E., Doll, K. M., Bensen, J. T., Gehrig, P. A., Wu, J. M., & Geller, E. J. (2016). Prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in women with suspected gynecological malignancy: a survey-based study. International Urogynecology Journal, 27(9), 1409–1414. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-2962-3

Ramaseshan, A.S., Felton, J., Roque, D., Rao, G., Shipper, A.G., Sanses, T.V.D. (2017). Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: a systematic review. International Urogynecology Journal. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3467-4

Lindgren, A., Dunberger, G., & Enblom, A. (2017). Experiences of incontinence and pelvic floor muscle training after gynaecologic cancer treatment. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(1), 157–166. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3394-9

While recently visiting Seattle with my daughter, we had the pleasure of talking with Dr. Ghislaine Robert, owner of Sparclaine Regenerative Medicine. She is a highly respected sports medicine doctor who has steered much of her practice towards regenerative medicine, with a focus on stem cell and platelet enriched plasma (PRP) injections. She brought to my attention the use of stem cells for pelvic floor disorders. And, like any successful practitioner, she encouraged me to research it for myself.

In 2015, Cestaro et al. reported early results of 3 patients with fecal incontinence receiving intersphincteric anal groove injections of fat tissue. They aspirated about 150ml of the fat tissue and used the Lipogem system technology lipofilling technique to provide micro-fragmented and transplantable clusters of lipoaspirate. The intersphincteric space was then injected with the lipoaspirate. A proctology exam was performed at 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months following the procedure. All 3 patients all had reduced Wexner incontinence scores 1 month post-treatment and a significant improvement in quality of life 6 months post-procedure. Resting pressure of the internal anal sphincter increased after 6 months, and the internal anal sphincter showed increased thickness.

A 2016 study by Mazzanti et al., used rats to explore whether unexpanded bone marrow-derived mononuclear mesynchymal cells (MNC) could effectively repair anal sphincter healing since expanded ones (MSC) had already been shown to enhance healing after injury in a rat model. They divided 32 rats into 4 groups: sphincterotomy and repair (SR) with primary suture of anal sphincters and a saline intrasphincteric injection (CTR); SR of anal sphincter with in-vitro expanded MSC; SR of anal sphincter with minimally manipulated MNC; and, a sham operation with saline injection. Muscle regeneration as well as contractile function was observed in the MSC and MNC groups, while the control surgical group demonstrated development of scar tissue, inflammatory cells and mast cells between the ends of the interrupted muscle layer 30 days post-surgery. Ultimately, the authors found no significant difference between expanded or unexpanded bone marrow stem cell types used. Post-sphincter repair can be enhanced by stem cell therapy for anal incontinence, even when the cells are minimally manipulated.

Finally, in 2017, Sarveazad et al. performed a double-blind clinical trial in humans using human adipose-derived stromal/stem cells (hADSCs) from adipose tissue for fecal incontinence. The hADSCs secrete growth factor and can potentially differentiate into muscle cells, which make them worth testing for improvement of anal sphincter incontinence. They used 18 subjects with sphincter defects, 9 undergoing sphincter repair with injection of hADSCs and 9 having surgery with a phosphate buffer saline injection. After 2 months, there was a 7.91% increase in the muscle mass in the area of the lesion for the cell group compared to the control. Fibrous tissue replacement with muscle tissue, allowing contractile function, may be a key in the long term for treatment of fecal incontinence.

As long as accessing human-derived stem cells is a viable option for patients, the preliminary studies show promise for success. With fecal incontinence being such a debilitating problem for people, especially socially, stem cells are definitely an up and coming treatment, and we should all keep up on this research. After all, who wouldn’t spare some adipose tissue for life-changing, functional gains?

Cestaro, G., De Rosa, M., Massa, S., Amato, B., & Gentile, M. (2015). Intersphincteric anal lipofilling with micro-fragmented fat tissue for the treatment of faecal incontinence: preliminary results of three patients. Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques, 10(2), 337–341. http://doi.org/10.5114/wiitm.2014.47435

Mazzanti, B., Lorenzi, B., Borghini, A., Boieri, M., Ballerini, L., Saccardi, R., … Pessina, F. (2016). Local injection of bone marrow progenitor cells for the treatment of anal sphincter injury: in-vitro expanded versus minimally-manipulated cells. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 7, 85. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-016-0344-x

Sarveazad, A., Newstead, G. L., Mirzaei, R., Joghataei, M. T., Bakhtiari, M., Babahajian, A., & Mahjoubi, B. (2017). A new method for treating fecal incontinence by implanting stem cells derived from human adipose tissue: preliminary findings of a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 8, 40. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-017-0489-2

Anxiety and depression are frequently encountered co-morbidities in the clients we serve in pelvic rehabilitation. This observation several years ago in clinical practice is one of many that prompted me down the path of exploring the connection between the gut, the brain, and overall health. In answering the question about these connections, I discovered many nutritionally related truths that are being rapidly elucidated in the literature.

A recent study by Sandhu, et.al. (2017) examines the role of the gut microbiota on the health of the brain and it’s influence on anxiety and depression. The title of the study, “Feeding the microbiota-gut-brain axis: diet, microbiome, and neuropsychiatry” gives us pause to consider the impact of our diets on this axis and in turn, on the health of our nervous system. The authors state:

It is diet composition and nutritional status that has been repeatedly been shown to be one of the most critical modifiable factors regulating the gut microbiota at different time points across the lifespan and under various health conditions.

With diet and nutritional status being the most critical modifiable factors in the health of this system, it becomes our responsibility to seek to understand this system and its influencing factors. We need to learn how to nourish the microbiota-gut-brain axis.

While anxiety and depression are common co-morbidities we encounter, we also commonly detect imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system in our patients leading to, for example, pelvic floor muscle tension. In light of this study we must first and foremost ask: what is the microbiota? How can it influence our nervous system? How does this correlate to anxiety and depression? The answers to these questions provide clinical insight with far-reaching impact. We also consider: which circumstances disrupt the health of this system and which improve it? Finally, could understanding of this axis, among other nutritional correlates, provide a novel approach to bowel dysfunction, bladder dysfunction, chronic pelvic pain?

Be a part of the paradigm shift to integrative understanding as we explore these and many other burning questions. Please join us for insightful discussion in White Plains, NY March 31-April 1, 2017 for our next offering of Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist.

Sandhu, K. V., Sherwin, E., Schellekens, H., Stanton, C., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2017). Feeding the microbiota-gut-brain axis: diet, microbiome, and neuropsychiatry. Transl Res, 179, 223-244. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2016.10.002

We are all familiar with the old saying, “You are what you eat.” A functional medicine lecture I attended recently at the Cleveland Clinic explained how chronic pain can be a result of how the body fails to process the foods we eat. Patients who just don’t seem to get better despite our skilled intervention make us wonder if something systemic is fueling inflammation. Even symptoms of vulvodynia, an idiopathic dysfunction affecting 4-16% of women, have been shown to correlate to diet.

In a single case study of a 28 year old female athlete in Integrative Medicine (Drummond et al., 2016), vulvodynia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) were addressed with an elimination diet. After being treated by a pelvic floor specialist for 7 months for vulvodynia, the patient was referred out for a nutrition consultation. Physical therapy was continued during the vegetarian elimination diet. In the patient’s first follow up 2 weeks after starting eliminating meat, dairy, soy, grains, peanuts, corn, sugar/artificial sweeteners, she no longer had vulvodynia. The nutrition specialist had her add specific foods every 2 weeks and watched for symptoms. Soy, goat dairy, and gluten all caused flare ups of her vulvodynia throughout the process. Eliminating those items and supplementing with magnesium, vitamin D3, probiotics, vitamin B12, and omega-3 allowed the patient to be symptom free of both vulvodynia and IBS for 6 months post-treatment.

On the more scientific end of research, Vicki Ratner published a commentary called “Mast cell activitation syndrome” in 2015. She described how mast cells appear close to blood vessels and nerves, and they release inflammatory mediators when degranulated; however, mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) involves mast cells that do not get degranulated properly and affect specific organs like the bladder. She proposed measuring the number of mast cells and inflammatory mediators in urine for more expedient diagnosis of interstitial cystisis and bladder pain syndrome.

On the more scientific end of research, Vicki Ratner published a commentary called “Mast cell activitation syndrome” in 2015. She described how mast cells appear close to blood vessels and nerves, and they release inflammatory mediators when degranulated; however, mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) involves mast cells that do not get degranulated properly and affect specific organs like the bladder. She proposed measuring the number of mast cells and inflammatory mediators in urine for more expedient diagnosis of interstitial cystisis and bladder pain syndrome.

Sigrid Regauer’s correspondence to Ratner’s article followed in 2016 relating MCAS to bladder pain syndrome (BPS), interstitial cystitis (IC), and vulvodynia. He described vulvodynia as a pain syndrome with excessive mast cells and sensory nerve hyperinnervation, often found with BPS and IC. The vulvodynia patients had mast cell hyperplasia, most of which were degranulated, and 70% of the patients had comorbidities due to mast cell activation such as food allergies, histamine intolerance, infections, and fibromyalgia.

Considering the association between mast cells and acute inflammatory responses and how mast cells release proinflammatory mediators, it makes sense that dysfunctions such as vulvodynia as well as IC and BPS can result from an excessive amount and dysfunctional granulation of mast cells. Enhanced activation of mast cells causes histamine release, stimulating peripheral pain neurotransmitters (Fariello & Moldwin 2015). If medication and therapy do not solve a patient’s pain, perhaps eliminating the consumption of inflammatory foods could positively affect the body on a cellular level and relieve irritating symptoms of vulvodynia. Pardon the parody, but patients on the brink of being “insane in the brain” from vulvodynia will likely try anything to resolve being “inflamed in the membrane.”

Drummond, J., Ford, D., Daniel, S., & Meyerink, T. (2016). Vulvodynia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Treated With an Elimination Diet: A Case Report.Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal, 15(4), 42–47.

Ratner, V. (2015). Mast cell activation syndrome. Translational Andrology and Urology, 4(5), 587–588. http://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.09.03

Regauer, S. (2016). Mast cell activation syndrome in pain syndromes bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis and vulvodynia. Translational Andrology and Urology, 5(3), 396–397. http://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2016.03.12

Fariello, J. Y., & Moldwin, R. M. (2015). Similarities between interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and vulvodynia: implications for patient management. Translational Andrology and Urology, 4(6), 643–652. http://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.10.09

In Megan Pribyl’s course on Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist, she discusses a wide variety of useful topics specific to nutrition and pelvic health. In her lecture on “Nutritional Homeostasis”, Megan counsels against missing an underlying eating disorder when working with a patient who has bowel issues. Work by Abraham and Kellow (2013) is cited, and in their article published in BMC Gastroenterology, the authors concur that many patients who have functional gastrointestinal complaints may also have disordered eating. How then, can we tell these patients apart, and get patients the most appropriate care? First let’s look at their research.

Patients who were admitted to a specialty unit for those with eating disorders in Australia were studied and were found to have conditions such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, polycystic ovarian syndrome, treated celiac disease, and treated bipolar depression. All of the 185 patients completed the Rome II Modular Questionnaire to identify symptoms consistent with functional gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction. They also completed the Eating and Exercise Examination which collected data about behaviors including objective binge eating, self-induced vomiting, laxative use and excessive exercise.

Patients who were admitted to a specialty unit for those with eating disorders in Australia were studied and were found to have conditions such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, polycystic ovarian syndrome, treated celiac disease, and treated bipolar depression. All of the 185 patients completed the Rome II Modular Questionnaire to identify symptoms consistent with functional gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction. They also completed the Eating and Exercise Examination which collected data about behaviors including objective binge eating, self-induced vomiting, laxative use and excessive exercise.

Esophageal discomfort (heartburn and chest pain of non cardiac origin) was associated with excess exercise (more than 5 days/week). Self-induced vomiting was identified primarily in the patients diagnosed with bulimia. One interesting finding the researchers noted is that for patients who have disorder eating, pelvic floor symptoms that are not associated with functional constipation are a prominent feature. This data begs the question, how can we best screen for disordered eating in patients who present with bowel dysfunction that otherwise may fit with the symptoms and presentation of patients who do not have disordered eating?

Our first step may be to include important conditions and symptoms on our written or computer-based intake forms. Is “disordered eating” or bulimia, anorexia-nervosa included on your intake forms for patients? What about symptoms like heartburn, laxative use, or vomiting? (As an important aside, I always remember being surprised by a patient who had urinary incontinence when she told me that she leaked with vomiting. She had gone through a gastric bypass surgery and would vomit several times per week as a reaction to difficulty digesting food. There may be a few good reason therefore to include vomiting on a checklist.) As pelvic rehab providers, we can understand how frequent vomiting may lead to dehydration, intrabdominal and intrapelvic pressure, potential pelvic floor dysfunction, or how disordered eating may lead to other bowel dysfunctions such as constipation and/or fecal incontinence. If we also hold space for eating issues to be a concern, we may find that asking some valuable questions provides more information.

If you would like to learn more about nutrition and the pelvic health connections, you still have time to sign up for Megan Pribyl’s nutrition course which takes place in Lodi, California this June!.

Abraham, S., & Kellow, J. E. (2013) "Do the digestive tract symptoms in eating disorder patients represent functional gastrointestinal disorders?" BMC gastroenterology, 13(1), 1.

If an infomercial played in pre-op waiting rooms explaining all the possible side effects or problems a patient may encounter after surgery, I wonder how many people would abort their scheduled mission. As if having an abdominal or pelvic surgery were not enough for a patient to handle, some unfortunate folks wind up with small bowel obstruction as a consequence of scar tissue forming after the procedure. Instead of having yet another surgery to get rid of the obstruction, which, in turn, could cause more scar tissue issues, studies are showing manual therapy, including visceral manipulation, to be effective in treating adhesion-induced small bowel obstruction.

Amanda Rice and colleagues published a paper in 2013 on the non-surgical, manual therapy approach to resolve small bowel obstruction (SBO) caused by adhesions as evidenced in two case reports. One patient was a 69 year old male who had 3 hernia repairs and a laparotomy for SBO with resultant abdominal scarring and 10/10 pain on the visual analog scale. The other patient was a 49 year old female who endured 7 abdominopelvic surgeries for various issues over the course of 30 months and presented with 7/10 pain and did not want more surgical intervention for SBO. Both patients received 20 hours of intensive manual physical therapy over a period of 5 days. The primary focus was to reduce adhesions in the bowel and abdominal wall for improved visceral mobility, but treatment also addressed range of motion, flexibility, and postural strength. The female patient reported 90% improvement in symptoms, with significant decreases in pain during bowel movements or sexual intercourse, and the therapist noted increased visceral and myofascial mobility. Both patients were able to avoid further abdominopelvic surgery for SBO, and both patients were still doing well at a one year follow up.

Amanda Rice and colleagues published a paper in 2013 on the non-surgical, manual therapy approach to resolve small bowel obstruction (SBO) caused by adhesions as evidenced in two case reports. One patient was a 69 year old male who had 3 hernia repairs and a laparotomy for SBO with resultant abdominal scarring and 10/10 pain on the visual analog scale. The other patient was a 49 year old female who endured 7 abdominopelvic surgeries for various issues over the course of 30 months and presented with 7/10 pain and did not want more surgical intervention for SBO. Both patients received 20 hours of intensive manual physical therapy over a period of 5 days. The primary focus was to reduce adhesions in the bowel and abdominal wall for improved visceral mobility, but treatment also addressed range of motion, flexibility, and postural strength. The female patient reported 90% improvement in symptoms, with significant decreases in pain during bowel movements or sexual intercourse, and the therapist noted increased visceral and myofascial mobility. Both patients were able to avoid further abdominopelvic surgery for SBO, and both patients were still doing well at a one year follow up.

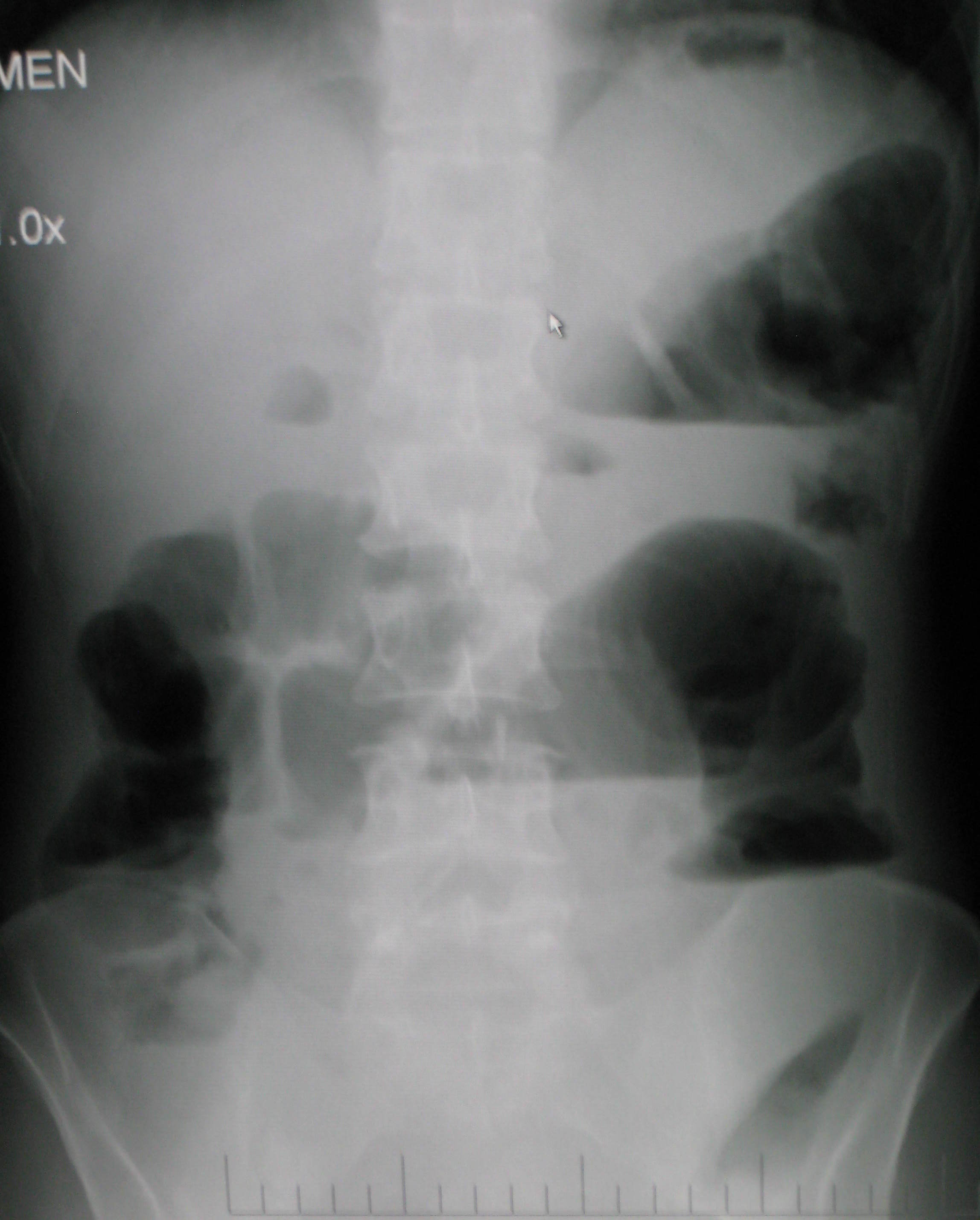

In 2016, a prospective, controlled survey based study by Rice et al., determined the efficacy of treating SBO with a manual therapy approach referred to as Clear Passage Approach (CPA). The 27 subjects enrolled in the study received this manual therapy treatment for 4 hours, 5 days per week. The CPA includes techniques to increase tissue and organ mobility and release adhesions. The therapist applied varying degrees of pressure across adhered bands of tissue, including myofascial release, the Wurn Technique for interstitial spaces, and visceral manipulation. The force used and the time spent on each area were based on patient tolerance. The SBO Questionnaire considered 6 domains (diet, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, medication, quality of life, and pain severity) and was completed by 26 of the subjects pre-treatment and 90 days after treatment. The results revealed significant improvements in pain severity, overall pain, and quality of life. Suggestive improvements were noted in gastrointestinal symptoms as well as tissue and organ mobility via improvement in trunk extension, rotation, and side bending after treatment. Overall, the authors conclude the manual therapy treatment of SBO is a safe and effective non-invasive approach to use, even for the pediatric population with SBO.

Myofascial release and visceral manipulation can disrupt the vicious cycle of adhesions causing small bowel obstruction after abdominopelvic surgical “invasion.” Learning specific techniques we may never have thought of can make a huge impact on certain patient populations. Quality of life for our patients often depends on how willing we are to increase our own knowledge and skill base.

Rice, A. D., King, R., Reed, E. D., Patterson, K., Wurn, B. F., & Wurn, L. J. (2013). Manual Physical Therapy for Non-Surgical Treatment of Adhesion-Related Small Bowel Obstructions: Two Case Reports . Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2(1), 1–12. PubMed Link

Rice, A. D., Patterson, K., Reed, E. D., Wurn, B. F., Klingenberg, B., King, C. R., & Wurn, L. J. (2016). Treating Small Bowel Obstruction with a Manual Physical Therapy: A Prospective Efficacy Study. BioMed Research International, 2016, 7610387. http://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7610387

Faculty member Lila Bartkowski- Abbate PT, DPT, MS, OCS, WCS, PRPC teaches the Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction and the Pelvic Floor course for Herman & Wallace. Join her in Tampa on April 2-3, or one of the other two events currently open for registration.

Constipation, an often under reported health issue, afflicts about 30% of Americans. ¹ The diagnosis of chronic constipation may seem like a simple concept, however the etiology of chronic constipation presents itself in many different forms. Dyssynergic defecation is one of many factors that can lead to a presentation of chronic constipation in a patient. Dyssynergic defecation or “paradoxical contraction” occurs when the muscles of the abdominals, puborectalis sling, and external anal sphincter function inappropriately while attempting a bowel movement. ² The lack of coordination of these muscles results in a contraction versus a lengthening of the pelvic floor muscles with baring down. Dyssynergic defecation is different than a structural issue such as a rectocele or hemorrhoids causing the inability to pass stool effectively or constipation due to slow colon transit time or pathological disease. Making the diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation by symptoms alone is often not reliable secondary to overlap of similar symptoms with chronic constipation due to factors such as a structural issue, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or irritable bowel disease (IBD). The diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation can be difficult and is often made through physiologic testing such as balloon expulsion testing or MRI with defecography. ² However, physical therapists can often manually feel that a paradoxical contraction is happening when asking a patient to bare down on evaluation.

Constipation, an often under reported health issue, afflicts about 30% of Americans. ¹ The diagnosis of chronic constipation may seem like a simple concept, however the etiology of chronic constipation presents itself in many different forms. Dyssynergic defecation is one of many factors that can lead to a presentation of chronic constipation in a patient. Dyssynergic defecation or “paradoxical contraction” occurs when the muscles of the abdominals, puborectalis sling, and external anal sphincter function inappropriately while attempting a bowel movement. ² The lack of coordination of these muscles results in a contraction versus a lengthening of the pelvic floor muscles with baring down. Dyssynergic defecation is different than a structural issue such as a rectocele or hemorrhoids causing the inability to pass stool effectively or constipation due to slow colon transit time or pathological disease. Making the diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation by symptoms alone is often not reliable secondary to overlap of similar symptoms with chronic constipation due to factors such as a structural issue, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or irritable bowel disease (IBD). The diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation can be difficult and is often made through physiologic testing such as balloon expulsion testing or MRI with defecography. ² However, physical therapists can often manually feel that a paradoxical contraction is happening when asking a patient to bare down on evaluation.

Patients with dyssynergic defecation may present to pelvic floor physical therapy with complaints of: ¹ ²

- Abdominal symptoms such as bloating, pain, and cramping

- Poor response to laxatives and fiber supplementation that does not fully resolve their issue

- Have had testing for anatomical or neurological abnormalities with no significant findings

- Complaints of concomitant pelvic pain due to over activity of the pelvic floor muscles

Physical Therapists specializing in pelvic floor rehab can be a valuable part of the medical team with treating these patients. Biofeedback training by physical therapists has been shown to decrease anorectal related constipation symptoms and abdominal symptoms in patients with dyssynergic defecation. In a sample of 77 patients with dyssynergic defecation, physical therapists provided biofeedback training for 6-8 weeks that included manual and verbal feedback, surface EMG, exercises using a rectal catheter, rectal ballooning to improve rectal sensory abnormalities, ultrasound, pelvic floor and abdominal massage, electrical stimulation if needed, and core strengthening and stretching to improve the patients’ maladaptive habits while attempting to pass a bowel movement. Significant decreases were seen on all three domains (abdominal, rectal, and stool) on the PAC-SYM (Patient Assessment of Constipation) questionnaire post biofeedback training. ² It is noteworthy that 74% of these patients presented to the clinic with complaints of abdominal symptoms such as bloating, pain, discomfort, and cramping.

Knowing how to effectively treat these patients and ask the right questions is valuable in the scheme of pelvic floor rehab secondary to overlapping symptoms of different causes of chronic constipation. Physical therapists are able to provide these patients with conservative treatment that can effectively improve or eliminate their problem, recognize dyssynergic defecation as a possible differential diagnosis, and refer to the appropriate medical professional for further testing. Recognizing and treating dyssynergic defecation is something physical therapists will learn how to become effective at in the upcoming Herman and Wallace Course: Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction & the Pelvic Floor April 2-3 in Tampa, FL and October 8-9 in Fairfield, CA.

1. Sahin M, Dogan I, Cengiz M et al. (2015). The impact of anorectal biofeedback therapy on quality of life of patients with dyssynergic defecation. Turk J Gastroenterol. 26(2):140-144

2. Baker J, Eswaran S, Saad R, et al. (2015). Abdominal symptoms are common and benefit from biofeedback therapy in patients with dyssynergic defecation. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 30(6)e105. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.3

As a child, I remember my grandmother rubbing my lower back to help me pass my stubborn stool, a problem which landed me in the hospital twice before I turned 10. Decades later, after the birth of my first baby, I had a grade III perineal tear that made me afraid I would never be able to control my stool from passing. At the time of each situation, I had no idea how many people of all ages experience the two extremes of bowel dysfunction. Thankfully, for patients struggling with either issue, whether it is chronic constipation or fecal incontinence, healthcare practitioners are becoming knowledgeable in how to treat both effectively through classes such as the Herman & Wallace course, “Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction & the Pelvic Floor.”

In 2014, Kelly Scott, MD, authored an article entitled, “Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence.” She reviews the current literature and notes this area of study lacks high quality randomized controlled trials, and further research is needed to provide evidence on the efficacy of different treatment protocols. Up to 24% of the adult population has been shown to experience fecal incontinence. Under the umbrella of pelvic floor rehabilitation lies pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback, rectal balloon catheters for volumetric training, external electrical stimulation, and behavioral bowel retraining. The goals of various biofeedback methods include the following: provide endurance training specifically for the anal sphincter and pelvic floor; improve rectal sensitivity and compliance; and, increase coordination and sensory discrimination of the anal sphincter. Overall, the success rate of pelvic floor rehabilitation for fecal incontinence in most of the studies is 50% to 80%, and it is considered safe as well as effective.

In 2014, Kelly Scott, MD, authored an article entitled, “Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence.” She reviews the current literature and notes this area of study lacks high quality randomized controlled trials, and further research is needed to provide evidence on the efficacy of different treatment protocols. Up to 24% of the adult population has been shown to experience fecal incontinence. Under the umbrella of pelvic floor rehabilitation lies pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback, rectal balloon catheters for volumetric training, external electrical stimulation, and behavioral bowel retraining. The goals of various biofeedback methods include the following: provide endurance training specifically for the anal sphincter and pelvic floor; improve rectal sensitivity and compliance; and, increase coordination and sensory discrimination of the anal sphincter. Overall, the success rate of pelvic floor rehabilitation for fecal incontinence in most of the studies is 50% to 80%, and it is considered safe as well as effective.

On the other end of the spectrum, Vazquez Roque and Bouras (2015) published an article regarding management of chronic constipation. Chronic constipation (CC) in the general population has a prevalence of 20%, and the elderly population has a higher rate than the younger population. Chronic constipation is commonly treated with stool softeners, fiber supplements, laxatives, and secretagogues. However, as in all areas of healthcare, a thorough examination needs to be performed to assess the source of the problem. Determining whether a patient exhibits slow transit constipation or a true pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) via blood work, rectal exam, and appropriate PFD tests is essential to provide the appropriate treatment. When the CC culprit is dysfunction of the pelvic floor, clinical trials have proven the efficacy of pelvic floor rehabilitation and biofeedback, making them optimal treatments.

When research indicates a particular type of rehabilitation is effective for treating a wide scope of issues in an area of the body, learning how and when to implement the techniques is paramount for a well-rounded practitioner. Most of us do not dream of treating chronic constipation or fecal incontinence; but, as we mature in our clinical practice, the spectrum of dysfunctions we discover through diagnostic testing and experience grows. Continuing education in previously unexplored territories can only expand the population to whom we provide relief.

Scott, K. M. (2014). Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 27(3), 99–105.

Vazquez Roque, M., & Bouras, E. P. (2015). Epidemiology and management of chronic constipation in elderly patients. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 919–930.