In a previous post on The Pelvic Rehab Report, Sagira Vora, PT, MPT, WCS, PRPC explored the impact that pelvic floor exercises can have on arousal and orgasm in women. Today we hear part two of the conversation, and learn what factors can impact a woman's ability to achieve orgasm.

“An orgasm in the human female is a variable, transient peak sensation of intense pleasure, creating an altered state of consciousness, usually with an initiation accompanied by involuntary, rhythmic contractions of the pelvic striated circumvaginal musculature, often with concomitant uterine and anal contractions, and myotonia that resolves the sexually induced vasocongestion and myotonia, generally with an induction of well-being and contentment.”

“An orgasm in the human female is a variable, transient peak sensation of intense pleasure, creating an altered state of consciousness, usually with an initiation accompanied by involuntary, rhythmic contractions of the pelvic striated circumvaginal musculature, often with concomitant uterine and anal contractions, and myotonia that resolves the sexually induced vasocongestion and myotonia, generally with an induction of well-being and contentment.”

Wow, that sounds like paradise! The question is--how to get there? Many of our cohorts and many our female patients have not experienced this or orgasm happens for them rarely. Findings from surveys and clinical reports suggest that orgasm problems are the second most frequently reported sexual problems in women. Some of the reasons cited for lack of orgasm are orgasm importance, sexual desire, sexual self-esteem, and openness of sexual communication with partner by Kontula el. al. in 2016. Rowland found that most commonly-endorsed reasons were stress/anxiety, insufficient arousal, and lack of time during sex, body image, pain, inadequate lubrication.

One factor that comes up consistently, is the ability of women to focus on sexual stimuli. This point has been brought up by various studies and presented in different ways. Chambless talks about mindfulness training and improvements in orgasm ability noted equally in women who practiced mindfulness vs. women who engaged in Kegels and mindfulness. Rosenbaum and Padua note in their book, The Overactive Pelvic Floor, “women who do not have a low-tone pelvic floor and who seek to enhance sexual arousal and more frequent orgasms have not much to gain from pelvic floor muscle training. Actually, a relaxed pelvic floor and mindful attention to sexual stimuli and bodily sensations seem a more effective means of enhancing sexual arousal and orgasm.” Various studies specifically studying the effect of mindfulness training have demonstrated both improved arousal and orgasm ability in women who practiced mindfulness. Brotto and Basson found their treatment group, which consisted of 68 otherwise healthy women, who underwent mindful meditation, cognitive behavioral training and education, improved in sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, sexual satisfaction, and overall sexual functioning.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy appears to play a significant role in improving sexual function in women. Meston et. al. notes, “cognitive behavioral therapy for anorgasmia focuses on promoting changes in attitudes and sexually relevant thoughts, decreasing anxiety, and increasing orgasmic ability and satisfaction. To date there are no pharmacological agents proven to be beneficial beyond placebo in enhancing orgasmic function in women.”

Alas, there are no magic pills to create the above described “state of altered consciousness,” allowing women a sense of “well-being and contentment.” However, mindfulness training and cognitive behavioral therapy are both accessible and attainable for women who want to improve their ability to enjoy this much desired state. Many Pelvic floor therapist incorporate cognitive behavioral and mindfulness approaches in their practice.

The studies above mention pain as one of the factors for inability to experience arousal and orgasm. Hucker and Mccabe even noted that their mindfulness treatment group demonstrated significant improvements in all domains of female sexual response except for sexual pain. Dealing with sexual pain is a daily battle pelvic floor therapist face each day. So, how do women with sexual pain dysfunction differ from women who are experiencing sexual dysfunction but not pain? Let’s explore this in our next blog…

Chambless DL, Sultan FE, Stern TE, O’Neill C, Garrison S. Jackson A. Effect of pubococcygeal exercise on coital orgasm in women. J Consult CLin Psychol. 1984; 52:114-8

Bratto LA, Basson R. Group mindfulness-based therapy significantly improves sexual desire in women Behav Res Ther. 2014 Jun; 57:43-5

Hucker A. Mccabe MP. Incorporating Mindfulness and Chat Groups Into an Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Mixed Female Sexual Problems. J Sex Res. 2015;52(6):627-33

Kontula O., Mettienen A. Determinants of female sexual orgasms. Socioaffect Neurosci Psychol. 2016 Oct 25;6:31624. doi: 10.3402/snp.v6.31624. eCollection 2016

Meston CM1, Levin RJ, Sipski ML, Hull EM, Heiman JR. Women’s orgasm. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2004;15:173-257. Review

Rosenbaum, Talli Y., Padoa, Anna. The overactive Pelvic floor. 1st ed. 2016

Roland DL, Cempel LM, Tempel AR. Women’s attributions on why they have difficulty reaching orgasm. J. Marital Therapy. 2018 Jan 3:0

In a previous post on The Pelvic Rehab Report Sagira Vora, PT, MPT, WCS, PRPC shared that "cognitive-behavioral therapy appears to play a significant role in improving sexual function in women". Today, in part three of her ongoing series on sex and pelvic health, Sagira explores how sexual pain affects sexual dysfunction in women.

After having explored what allows for women to have pleasurable sexual experiences including pain-free sex and mind-blowing orgasms, we now turn towards our cohort that have pain with sex and intimacy. How does this group differ from women who do not have pain with sex? Are there some common factors with this group of women, and perhaps understanding these factors may help the pelvic floor therapist render more effective and successful treatment?

After having explored what allows for women to have pleasurable sexual experiences including pain-free sex and mind-blowing orgasms, we now turn towards our cohort that have pain with sex and intimacy. How does this group differ from women who do not have pain with sex? Are there some common factors with this group of women, and perhaps understanding these factors may help the pelvic floor therapist render more effective and successful treatment?

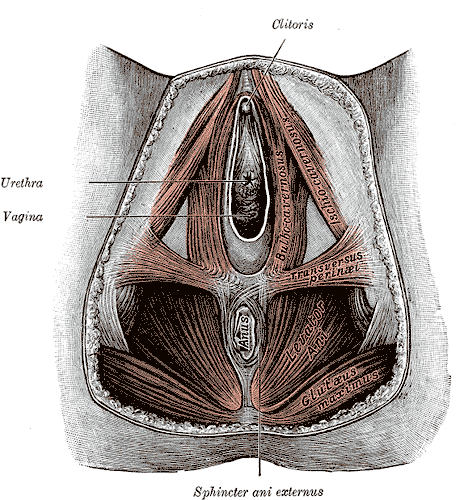

There are few studies exploring sexual arousal in women with sexual pain disorders. However, their findings are remarkable. Brauer and colleagues found that genital response, as measured by vaginal photoplethysmography and subjective reports, was found to be equal in women with sexual pain vs. women who did not have pain, when they were shown oral sex and intercourse movie clips. This and other studies have shown that genital response in women with dyspareunia is not impaired. Genital response in women with dyspareunia is however, effected by fear of pain. When Brauer and colleagues subjected women with dyspareunia to threat of electrical shock (not actual shock) while watching an erotic movie clip they found that women with dyspareunia had much diminished sexual response including diminished genital arousal. But Spano and Lamont found that genital response was diminished by fear of pain equally in women with sexual pain and women without sexual pain.

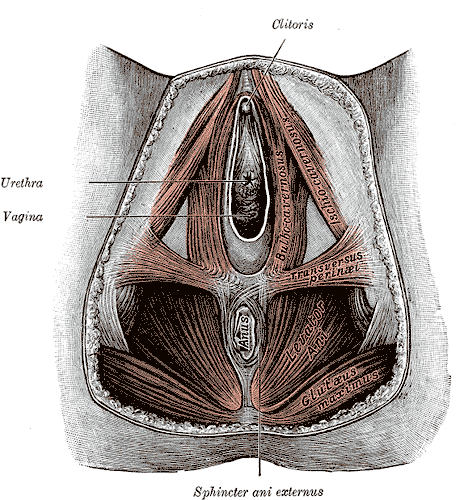

Fear of pain also resulted in increased muscle activity in the pelvic floor. However, this increase was noted in women with pain and women without sexual pain equally and was noted with exposure to sexually threatening film clips as well as threatening film clips without sexual content. The conclusion, then, from these results is that the pelvic floor plays a role in emotional processing and tightening, or overactivity is a protective response noted in all women regardless of sexual pain history.

The one difference that was noted was with women who had the experience of sexual abuse. For them, pelvic floor overactivity was noted when watching sexually threatening as well consensual sexual content. Women without sexual abuse history did not have increased pelvic floor activity when watching consensual sexual content.

In summary, evidence supports the hypothesis that women with sexually adverse experiences tend to have impaired genital response when in consensual sexual situations, however, women who do not have sexual abuse histories and but have sexual pain tend to have appropriate genital response. Both groups, however, have increased pelvic floor muscle activity in consensual sexual situations. This increase in pelvic floor muscle activity leads to muscle pain, reduced blood flow, reduced lubrication, increased friction between penis and vulvar skin and hence leads to pain.

This brings us to our next questions, how does the cohort that has had adverse sexual experiences present? How do women with history of sexual trauma process sexual experiences? How does the pelvic floor present or respond to consensual sexual situations when a woman has been abused in the past? Please tune in to the next blog for answers…

Blok BF, Holstege G. The neuronal control of micturition and its relation to the emotional motor system. Prog Brain Res. 1996; 107:113-26

Brauer M, Laan E, ter Kuile MM. Sexual arousal in women with superficial dyspareunia. Arch Sex Behav. 2006; 35:191-200

Brauer M, ter Kuile MM, Janssen S, Lann E. The effect of pain-related fear on sexual arousal in women with superficial dyspareunia. Eur J Pain: 2007; 11:788-98

Spano L, Lamont JA. Dyspareunia: a symptom of female sexual dysfunction. Can Nurse 1975;71:22-5

Episiotomy is defined as an incision in the perineum and vagina to allow for sufficient clearance during birth. The concept of episiotomy with vaginal birth has been used since the mid to late 1700’s and started to become more popular in the United States in the early 1900’s. Episiotomy was routinely used and very common in approximately 25% of all vaginal births in the United States in 2004. However, in 2006, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended against use of routine episiotomies due to the increased risk of perineal laceration injuries, incontinence, and pelvic pain. With this being said, there is much debate about their use and if there is any need at all to complete episiotomy with vaginal birth.

What are the negative outcomes of episiotomy?

What are the negative outcomes of episiotomy?

The primary risks are severe perineal laceration injuries, bowel or bladder incontinence, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and pelvic floor laxity. Use of a midline episiotomy and use of forceps are associated with severe perineal laceration injury. However, mediolateral episiotomies have been indicated as an independent risk factor for 3rd and 4th degree perineal tears. If episiotomy is used, research indicates that a correctly angled (60 degrees from midline) mediolateral incision is preferred to protect from tearing into the external anal sphincter, and potentially increasing likelihood for anal incontinence.

What are the indications for episiotomy, if any?

This remains controversial. Some argue that episiotomies may be necessary to facilitate difficult child birth situations or to avoid severe maternal lacerations. Examples of when episiotomy may be used could include shoulder dystocia (a dangerous childbirth emergency where the head is delivered but the anterior shoulder is unable to pass by the pubic symphysis and can result in fetal demise.), rigid perineum, prolonged second stage of delivery with non reassuring fetal heart rate, and instrumented delivery.

On the other side of the fence, many advocate never using an episiotomy due to the previously stated outcomes leading to perineal and pelvic floor morbidity. In a recent cohort study in 2015 by Amorim et al., the question of “is it possible to never perform episiotomy with vaginal birth?” was explored. 400 women who had vaginal deliveries were assessed following birth for perineum condition and care satisfaction. During the birth there was a strict no episiotomy policy and Valsalva, direct pushing, and fundal pressure were avoided, and perineal massage and warm compresses were used. In this study there were no women who sustained 3rd or 4th degree perineal tears and 56% of the women had completely intact perineum. 96% of the women in the study responded that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their care. The authors concluded that it is possible to reach a rate of no episiotomies needed, which could result in reduced need for suturing, decreased severe perineal lacerations, and a high frequency of intact perineum’s following vaginal delivery.

Are episiotomies actually being performed less routinely since the 2006 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendation?

Yes, a recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association by Friedman, it showed that the routine use of episiotomy with vaginal birth has declined over time likely reflecting an adoption of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations. This is ideal, as it remains well established that episiotomy should not be used routinely. However, indications for episiotomy use remain to be established. Currently, physicians use clinical judgement to decide if episiotomy is indicated in specific fetal-maternal situations. If one does receive an episiotomy then a mediolateral incision is preferred. The World Health Organization’s stance is that an acceptable global rate for the use of episiotomy is 10% or less of vaginal births. So the question still remains, (and of course more research is needed) to episiotomy or not to episiotomy?

Amorim, M. M., Franca-Neto, A. H., Leal, N. V., Melo, F. O., Maia, S. B., & Alves, J. N. (2014). Is It Possible to Never Perform Episiotomy During Vaginal Delivery?. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 123, 38S.

Friedman, A. M., Ananth, C. V., Prendergast, E., D’Alton, M. E., & Wright, J. D. (2015). Variation in and Factors Associated With Use of Episiotomy. JAMA, 313(2), 197-199.

Levine, E. M., Bannon, K., Fernandez, C. M., & Locher, S. (2015). Impact of Episiotomy at Vaginal Delivery. J Preg Child Health, 2(181), 2.

Melo, I., Katz, L., Coutinho, I., & Amorim, M. M. (2014). Selective episiotomy vs. implementation of a non episiotomy protocol: a randomized clinical trial. Reproductive health, 11(1), 66.

Leg length discrepancy (LLD) is when there is a noticeable difference in length of one leg to the other. LLD is common and can be found in 70% of the population (Gurney, 2002). LLD can be structural or functional. Structural LLD is when a long bone in the leg is longer or shorter than the other. Structural LLD is often the result of congenital or boney damage of epiphyseal plate. Functional is when there is an apparent LLD from higher in the chain such as scoliosis. Generally as pelvic floor therapists we are orthopedic based therapists. In physical therapy school we learned that a leg length discrepancy had to be >1 cm to be considered significant, and based off of recent research that is still the case. Research in the last few years has focused on whether LLD has an effect on age related changes with osteoarthritis, posture & gait, and pain. Physiopedia suggests differential diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction, scoliosis, low back pain, iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome, stress fractures, and pronation. It can often feel like a chicken or egg question.

In the clinic I typically screen for a leg length discrepancy during my initial evaluation. A LLD may be noticed upon observation of gait assessment, standing posture, or part of the pelvic obliquity screen in standing and then in supine.

In the clinic I typically screen for a leg length discrepancy during my initial evaluation. A LLD may be noticed upon observation of gait assessment, standing posture, or part of the pelvic obliquity screen in standing and then in supine.

During gait, a LLD will create bilaterteral gait impairments. Khamis et al did a systematic review of LLD and gait deviations in 2017. They narrowed the search down to 12 articles and found that LLD >1cm was significantly related to gait deviations. These deviations occurred bilaterally, and while initially compensations occurred in the sagittal plane, as the LLD increased so did the gait deviations, and then affected frontal planes of motion as well. Resende et al (2016) agrees that even mild LLD should not be overlooked. They found that the most likely gait deviations were also in the sagittal planes and consisted of rearfoot and ankle dorsiflexion and inversion, knee flexion and adduction, hip adduction and flexion, and pelvic trendelenburg.

The sagittal, or right/left plane, and frontal, or front/back, plane involvement is consistent with the differential diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction, low back pain, and pronation. Really, one could justify why a LLD could contribute to pain and dysfunction in most of the lower body. It is reasonable to think that these compensational moments in gait over a long period create boney changes in the lower extremities which may contribute to low back pain.

Clinically, a leg length discrepancy can be assessed directly with a tape measure or indirectly with a shoe lift. Badii (2014) found a higher interrater reliability with the indirect method of a shoe lift as opposed to measuring with a tape measure.

Rannisto et al (2019) looked at leg length discrepancy among meat cutters with low back pain. All participants had been working for 10 years and were greater than 35 years old. Participants needed to have a LLD of 5mm (5mm is 0.5 cm) or more and complain of low back pain of >2/10 on visual analog scale (VAS). They were all given insoles and randomized into 2 groups; the intervention group were given lifts to correct the LLD about 70%; for example a 10mm LLD was corrected to 3 mm. The LLD was measured with a laser ultrasound technique. Participants were followed for 12 months. The intervention group had improvement in low back pain intensity, sciatica intensity, and took less sick time. Possibly the most amazing part is that for those that wore the heel lift at work the compliance was good.

Leg length discrepancy can often be an underlying component contributing to complaints of pain and dysfunction. It may have more of an effect on the populations who stand or walk for most of their work, and I wonder as more people transition to standing desks if we will see more people come into the clinic with a previously undiagnosed LLD.

My biggest clinical pearls from this research is that:

- Heel lifts can be used to diagnose and then for treatment (yay! One less step of getting the tape measure out)

- The heel lift does not have to be perfect. Clinically, I will try a lift and have the person walk, and then we can make a team decision if this lift is enough and feels better

- The gait compensations are consistently adduction and internal rotation throughout the lower body chain. I will continue to work on the opposing muscle groups; lateral rotators, hip extensors and abductors.

Leg Length Discrepancy can be evaluated using various assessments. To learn orthopedic evaluative techniques for patients, consider joining Lila Abbate in her course Advanced Orthopedic Assessment for the Pelvic Health Therapist.

Maziar Badii, A Nicole Wade, David R Collins, Savvakis Nicolaou, B Jacek Kobza, Jacek A Kopec, Comparison of lifts versus tape measure in determining leg length discrepancy; Journal of Rheumatology 2014, 41 (8): 1689-94

Renan A. Resende, Renata N. Kirkwood, Kevin J. Deluzio, Silvia Cabral, Sérgio T. Fonseca. "Biomechanical strategies implemented to compensate for mild leg length discrepancy during gait" Gait & Posture, Volume 46, 2016; 147-153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.03.012

Sam Khamis, Eli Carmeli, Relationship and significance of gait deviations associated with limb length discrepancy: A systematic review, Gait & Posture, Volume 57, 2017, 115-123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.05.028

Burke Gurney, Leg length discrepancy, Gait & Posture, Volume 15, Issue 2, 2002, Pages 195-206, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00148-5.

Satu Rannisto, Annaleena Okuloff, Jukka Uitti, et al. Correction of leg-length discrepancy among meat cutters with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2019;(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2478-3.

Everyday we as pelvic rehab providers get to help patients achieve their goals by meeting them where they are and guiding them along.

A couple of months ago I had a new patient come in to see me who was seven months status post c-section delivery of her first child. She was referred to physical therapy because she could not tolerate anything touching her lower abdomen and she was also unsure of how to start exercising again including returning to her yoga practice. I remember reading her referral and thinking that this should be a simple evaluation and treatment session. What actually happened was a little different.

Her delivery hadn’t gone the way she planned, and she was not comfortable discussing it at our first session. This patient had not looked at or touched her c-section incision besides drying it off after her shower for the seven months since delivery. Her physician had made a referral to PT and to a counselor within three months of delivery to help support the patients’ recovery. The patient had not followed through with the PT referral until she had significant encouragement from her counselor and physician.

Initially the patient declined any observation or palpation of her abdomen so at our first session we focused on thoracic range of motion, general posture, and encouraged her to start touching her abdomen through her clothes, even if avoiding direct touch to the incisional region. The patient was agreeable with this starting point. At the second session the patient was willing to have me look at her abdomen and touch the abdomen but she declined direct palpation of the scar region. With simple observation I could see a scar that was closed and healing but also that was pulled inferior towards her pubic bone. She was not comfortable laying flat on the treatment table and had to be supported in a semi-recline throughout the session. She also described buzzing symptoms at the scar region when she reached her arms overhead.

We started some gentle desensitization techniques as would be used with a person that had Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) after an injury. I focused those treatments to the abdominal region but avoided the scar region. We focused her home program on breathing into her abdomen allowing some stretch and expansion of the abdominal region. Her home program also included laying flat for five minutes per day. I asked her to notice any general tension throughout her body during the day and attempt to change it and release it if able.

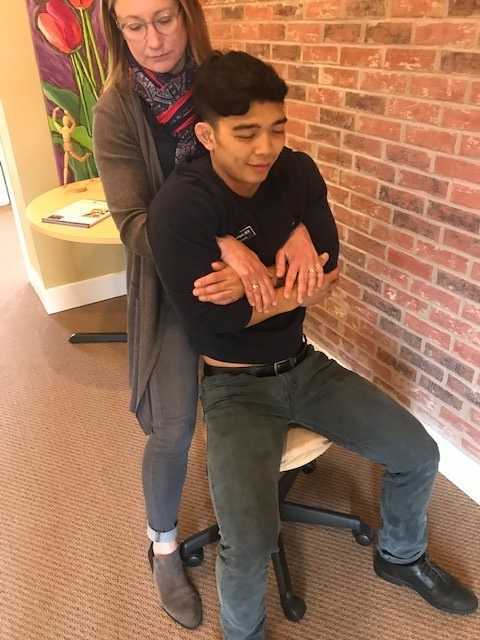

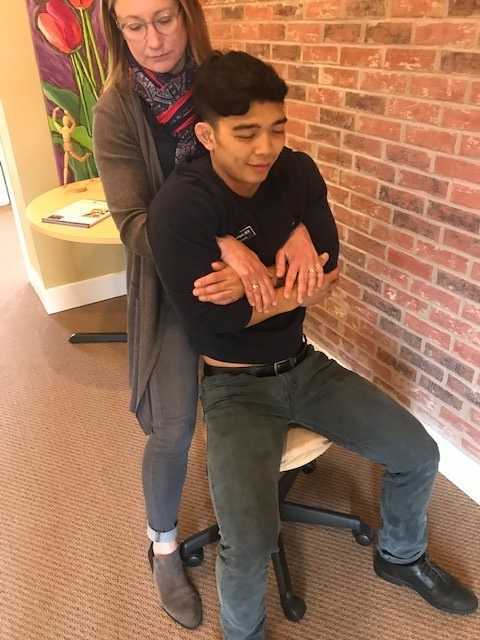

By the fourth session we where able to begin direct palpation and manual therapy techniques to the c-section scar and the whole abdominal region. The patient was apprehensive but agreed to proceeding with utilizing techniques as described by Wasserman et al2018 including superficial skin rolling, direct scar mobilization and general petrissage/effleurage of the abdomen and lumbothoracic region.

Over the next five sessions the patient was able to start wearing undergarments and pants that touched her lower abdomen. She was able to perform her own self massage to the region and began an exercise program including prone press ups, progressive generalized trunk strengthening, and return to her prior-to-pregnancy yoga practice.

Drawing on the techniques we learn from multiple sources, applying them to the lumbopelvic region, and helping our patients wherever the client is in their journey to wellness, is what inspires me to keep learning.

Techniques like this are taught in my 2-day Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist course. I specifically wrote this course so that pelvic rehab therapists that are looking for more techniques and/or more confidence in their palpation skills would have a weekend to hone those skills. We spend time learning anatomy, learning palpation skills, manual techniques, problem solving home programs and discussing cases. Check out Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist - Raleigh, NC - June 22-23, 2019 for more information and I hope to see you there.

Wasserman, J. B., Abraham, K., Massery, M., Chu, J., Farrow, A., & Marcoux, B. C. (2018). Soft Tissue Mobilization Techniques Are Effective in Treating Chronic Pain Following Cesarean Section: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 42(3), 111-119.

In the United States, estimated direct medical costs for outpatient visits for chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is more than $2.8 billion per year.1 In a 2017 study in the Clinical Journal of Pain by Sanses et al, a detailed musculoskeletal exam of clients with CPP can assist both physicians as well as physical therapists in differential diagnosis and appropriate referrals for this population.

Evaluating a client with pelvic pain requires a skill set that includes direct pelvic floor as well as musculoskeletal test item clusters. The prioritization of which depends upon many factors including clinician discipline, experience, specialty vs. general setting, as well as client history, presentation and goals. In addition to the direct pelvic floor assessment, there are additional key musculoskeletal screening tests that are an essential part of a pelvic pain assessment. New this year, my course Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain will incorporate the use of Real Time Ultrasound in neuromuscular assessment and re-education of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall during the Sunday morning lab session.

Peery et al (2012) noted that abdominal pain was one of the most common presenting reasons for an outpatient physician visit in the United States. Abdominal pain is one of the many complaints that our clients may report requiring differential diagnosis including urogynecologic, colorectal, musculoskeletal, visceral or neurogenic causes. Lower abdominal quadrant pain may denote serious emergent pathology. Clinical findings, physical exam and client symptoms in addition to smart differential diagnosis must be used to determine if the abdominal pain is musculoskeletal in nature. Direct access requires physical therapists to perform a skilled initial screening for abdominal pain in order to determine if it is abdominal wall versus a visceral origin. Physicians are fluent in ruling out emergent pathology but may not be familiar with musculoskeletal tests for non-emergent pathology. Assessment of bowel and bladder function and habits are essential to perform. This blog specifically addresses three physical exam tests that can be performed as part of abdominal wall pain screening. According to Cartwright et al, the location of the abdominal pain should drive the evaluation.

Carnett’s test is a simple clinical test that assesses abdominal pain response when a client tenses their abdominal muscles. A positive Carnett’s sign denotes the origin of symptoms within the abdominal wall with a negative tests suggesting intra-abdominal pathology. The test is performed in supine, the clinician gently palpating the area of abdominal pain and has the client lift their head and shoulders off the table. Conditions such as myofascial trigger points, scar and muscular pain would be flared with palpation of the contractile tissue with activation of the abdominal wall muscles. If the pain is due to visceral origin, appendicitis for example, the pain would remain unchanged with palpation with head lift. Although some perform Carnett’s test by lifting both legs off the table, this method may cause unnecessary pain in clients with poor lumbopelvic control. (Figure 1) The head and shoulder lift option is felt to be comparable method of performing Carnett’s test.

Blumberg’s sign is most commonly used to rule in appendicitis, peritonitis or a visceral driver of right lower quadrant pain. The test is performed by the clinician applying deep pressure over McBurney’s point (Figure 2) with an abrupt and rapid release of pressure. Although there are anatomical variations in appendix location, pain reproduction is consistent with a positive test and immediate referral to the ER is indicated.

Thoracic dysfunction, including disc herniation, can result in abdominal pain.2 In thoracic discogenic driven abdominal pain, symptoms would likely be exacerbated by coughing, sneezing, spinal flexion and activities that would increase spinal loading. A simple screening for this is seated thoracic traction. If the client reports reduction or resolution of symptoms with traction, further musculoskeletal tests including regional movement and PIVM testing could be implemented to rule in or rule out need for diagnostic imaging.

In the Herman Wallace course “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain” participants learn a comprehensive musculoskeletal screen including abdominal, neural mobility and conductivity, pelvic ring, pelvic floor and biomechanical contributing factors to pelvic pain. Evidence based test item clusters are defined, along with their diagnostic accuracy, for all associated systems in order to outline a comprehensive screen for pelvic pain clients. To learn more about musculoskeletal screening for pelvic pain, check out faculty member Elizabeth Hampton PT, DPT, WCS, PRPC, BCB-PMD’s course Finding the Driver of Pelvic Pain, which is next offered Jun 28, 2019 - Jun 30, 2019 in Columbus, Ohio. We are fortunate to have Dick Poore, President of The Prometheus Group present on Sunday June 30th for technical support for the Real Time Ultrasound portion of the course.

1. Sanses et al. "The Pelvis and Beyond: Musculoskeletal Tender Points in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain". Clin. J. Pain. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000307

2. Papadakos et al. "Thoracic Disc Prolapse Presenting with Abdominal Pain: Case Report and Review of the Literature". Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 20019 Jul. doi: 10.1308/147870809X401038

“My butt hurts.” This is such a common subjective complaint in my practice as a manual therapist, and many patients insist it must be a muscle problem or jump to the conclusion it must be “sciatica.” I often tell patients if they did not get shot or bit directly in the buttocks, the pain is most likely referred from nerves that originate in the spine. Although blunt trauma to the buttocks can certainly be the culprit for pain in the gluteal region, a basic understanding of the neural contribution is essential for providing appropriate treatment and a sensible explanation for patients.

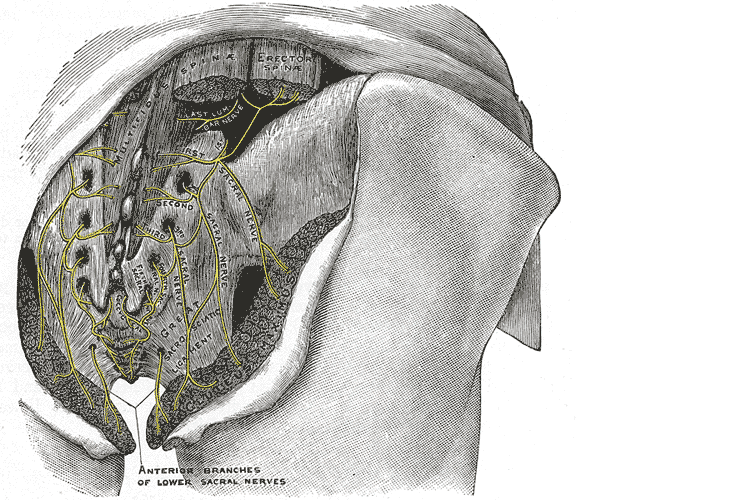

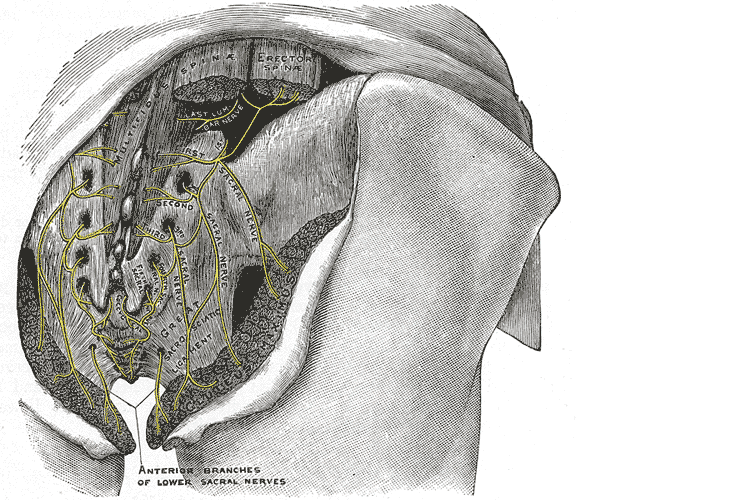

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

Iwananga et al., (2018) presents a very recent article regarding the innervation of the piriformis muscle, which has been suspected to be the superior gluteal nerve, by dissecting each side from ten cadavers. Often the piriformis muscle can be compromised through total hip replacements with a posterior approach, hip injuries, or chronic pain disorders. This particular study verifies there is no singular nerve that innervates the piriformis muscle, and the most common innervation sources are the superior gluteal nerve (70% of the time) and the ventral rami of S1 (85% of the time) and S2 (70% of the time). The inferior gluteal nerve and the L5 ventral ramus were each found to be part of the innervation only 5% of the time.

Wang et al., (2018) focused on what causes gluteal pain with lumbar disc herniation, particularly at L4-5, L5-S1. They emphasize the important factor that dorsal nerve roots have sensory fibers and ventral roots contain motor neurons, and spinal nerves are mixed nerves, since they have ventral and dorsal roots. They discuss other contributing nerves, but continuing our focus on the superior gluteal nerve, it stems from L4-S1 ventral rami and not only allows movement of gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and gluteus maximus, it also provides sensation to the area. This nerve can certainly produce pain in the gluteal region when irritated. In lumbar disc herniation of L4-5 or L5-S1, the ventral rami of L5 or S1 can be comprised or irritated at the level of the nerve root and provoke gluteal pain because they mediate sensation in that area.

Once the superior gluteal nerve (or any sacral nerve) is implicated as the root of pain, should we just shrug our shoulders and send them to pain management? I strongly suggest we learn how to address the issue in therapy using our hands with manual techniques and appropriate exercises. The Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment course should be a priority on your bucket list of continuing education to help alleviate any further pain in the butt.

Lung K, Lui F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Superior Gluteal Nerve. [Updated 2018 Dec 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535408/

Iwanaga J, Eid S, Simonds E, Schumacher M, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. (2018). The Majority of Piriformis Muscles are Innervated by the Superior Gluteal Nerve. Clinical Anatomy. doi: 10.1002/ca.23311. [Epub ahead of print]

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Yan, Y., Zhang, L., Guo, C., Peng, Z., & Kong, Q. (2018). Possible pathogenic mechanism of gluteal pain in lumbar disc hernia. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 19(1), 214. doi:10.1186/s12891-018-2147-y

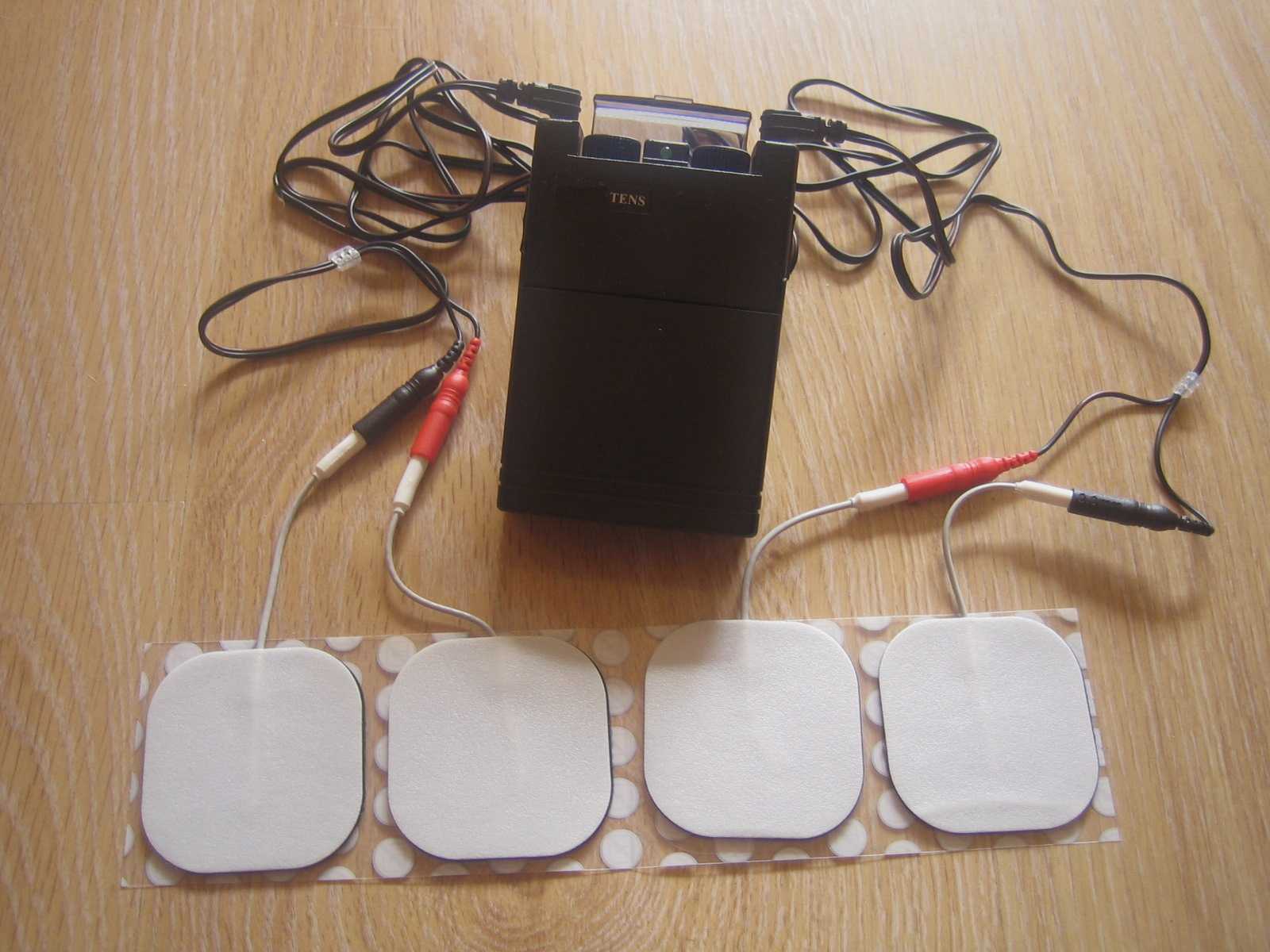

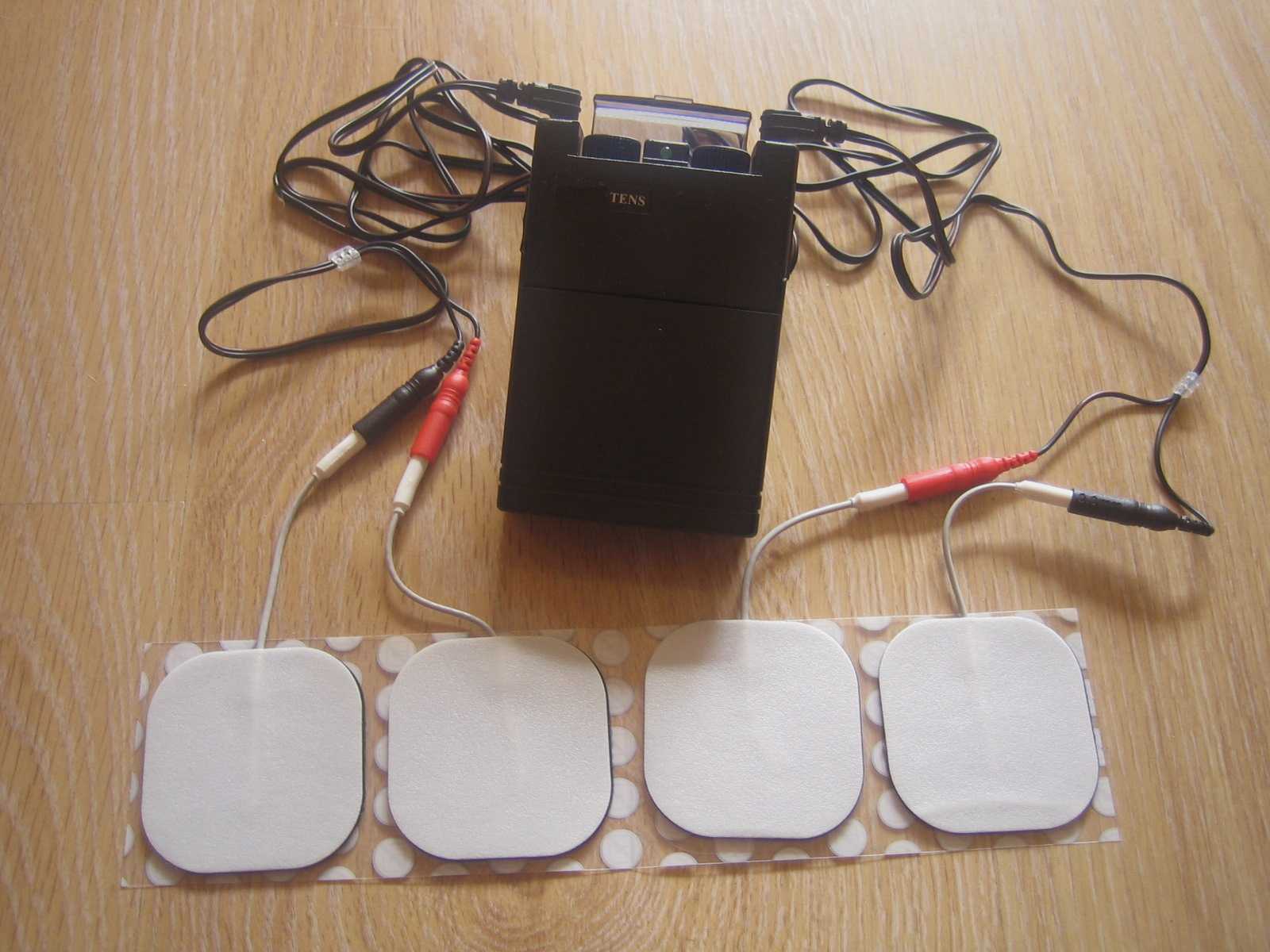

Tibial nerve stimulation has been shown in the literature to be effective for individuals experiencing idiopathic overactive bladder in randomized controlled trials. A systematic review was performed by Schneider, M.P. et al. in 2015 looking at safety and efficacy of its use in neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Many variables were examined in this review, which included 16 studies after exclusion. The review looked at:

- Acute stimulation (used during urodynamic assessment only)

- Chronic stimulation (6-12 weeks of daily-weekly use)

- Percutaneous or transcutaneous (frequencies, pulse widths, perception thresholds, durations)

- Urodynamic parameter changes baseline to post treatment

- Post void residual changes

- Bladder diary variables

- Patient adherence to tibial nerve stimulation

- Any adverse events

The exact mechanism of these types of neuromodulation stimulation procedures remains unclear, however it does appear to play a role in neuroplastic reorganization of cortical networks via peripheral afferents. No specific literature is currently available for the mechanism on action related to neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Different applications of neuromodulation however have been studied in the neurogenic populations.

One of the randomized controlled trials they report on included 13 people with Parkinson disease. The researchers looked at a comparison between the use of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (n = 8) and sham transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (n=5). Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) or sham stimulation was delivered to the people with Parkinson disease 2x/week for 5 weeks, 30-minute sessions (10 total sessions). Unilateral electrode placement was utilized, first electrode applied below the left medial malleolus and second electrode 5 cm cephalad. Confirmation of placement was obtained with left great toe plantar flexion. It is important to note the use of the stimulation intensity is reduced to below the motor threshold during the active treatment to direct the stimulation via peripheral afferents.

Urodynamic testing was performed at baseline and post treatment and revealed statistically significant differences with greater volumes at strong desire and urgency in the TTNS group. Additionally, the TTNS group experienced a 50% reduction in nocturia whereas in the sham group nocturia frequency remained the same. A three-day bladder diary completed by each of the groups also revealed significant positive changes in frequency, urgency, urge urinary incontinence and hesitancy only in the TTNS group.

Conservative management of neurogenic bladder in populations such as Parkinson disease is very important. These individuals experience lower quality of life ratings related to lower urinary tract dysfunction, higher risk of falling with needs to rush to the bathroom, their caregivers experience a higher level stress and burden of care, and tolerance to anticholinergic medications is very poor with multiple unwanted side effects that compound and worsen other symptoms that might be present from the disease process.

Please join us for Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab to learn how you can help your patients using this modality as one option. Participate in a lab session to learn electrode placement and other parameters to achieve best clinical results for your patients.

1. Perissinotto, M. C., D'Ancona, C. A. L., Lucio, A., Campos, R. M., & Abreu, A. (2015). Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms and its impact on health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 42(1), 94-99.

2. Schneider, M. P., Gross, T., Bachmann, L. M., Blok, B. F., Castro-Diaz, D., Del Popolo, G., ... & Kessler, T. M. (2015). Tibial nerve stimulation for treating neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: a systematic review. European urology, 68(5), 859-867.

The following is the first in a series on self-care and preventing practitioner burnout from faculty member Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC. Jennafer is the co-author and co-instructor of the Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation course along with Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC.

Part 1: Boundaries

“I just want you to fix me.” How many times have we heard this statement from our patients? And how do we respond? In my former life as a “rescuer” this statement would be a personal challenge. I wanted to be the fixer, find the solution and identify the thing that no one else had seen yet. Then, if I am being completely honest, bask in the glory of being the “miracle worker” and “never giving up” on my patient.

If you recognize that this attitude was going to run me into some problems, kudos to you. If you are thinking, “well of course, isn’t that your job as a pelvic floor physical therapist?” Please read on.

If you recognize that this attitude was going to run me into some problems, kudos to you. If you are thinking, “well of course, isn’t that your job as a pelvic floor physical therapist?” Please read on.

On my very first job performance review, when it came time to discuss my problem areas my supervisor relayed I was “too nice” and cited some examples: giving a patient a ride home after therapy (it was raining and she would have had to wait for the bus), coming in on Saturdays to care for patients (he was sick and couldn’t make it in during the week but was making really good progress). You get the picture. At the time, I didn’t understand how this could be something I needed to work on. I was going above and beyond and I got so much satisfaction from taking care of others!

Fast forward 10 years and add to my life a husband, two daughters, a teaching job, part time homeschooling, and writing course material. I was an emotional mess. Anxiety was my permanent state of mind. I gave my best to my patients while my family got my meager emotional leftovers. Something had to change and luckily it did. I got help and learned exactly what boundaries are and how to develop as well as enforce them.

There are several resources that discuss professional boundaries in health care, like this from Nursing Made Incredibly Easy. In this particular article, health care professionals are exhorted to stay in the “zone of helpfulness” and avoid becoming under involved or over involved with patients. Health care professionals are also urged to examine their own motivation. Am I using my relationship with my patient to fulfill my own needs? Am I over involved so that I can justify my own worth?

Here are some warning signs that you are straying away from healthy boundaries with patients and becoming over involved:

- Discussing your intimate or personal issues with a patient

- Spending more time with a patient than scheduled or seeing a patient outside of work

- Taking a patient's side when there's a disagreement between the patient and his or her close relations

- Believing that you are the only health care member that can help or understand a patient

For some people, certain patients who push professional boundaries will cause the therapist to feel threatened and under activity is the result. This might result in talking badly about the patient to other staff, distancing ourselves, showing disinterest in their case, or failing to utilize best care practices for the patient.

Per Remshard 2012, “When you begin to feel a bit detached, stand back and evaluate your interactions. If you sense that boundaries are becoming blurred in any patient care situation, seek guidance from your supervisor. A sentinel question to ask is: ‘Will this intervention benefit the patient or does it satisfy some need in me?’”

Healthy professional boundaries are imperative for us and for our patients. Boundaries also help prevent burnout. Remshard delineates what healthy boundaries look like:

- Treat all patients, at all times, with dignity and respect.

- Inspire confidence in all patients by speaking, acting, and dressing professionally.

- Through your example, motivate those you work with to talk about and treat patients and their families respectfully.

- Be fair and consistent with each patient to inspire trust, amplify your professionalism, and enhance your credibility.

If you struggle with professional and personal boundaries, you are not alone and you can get support. Consider talking with your supervisor, a counselor, reading a good book on the subject or taking Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation, a course offering through Herman and Wallace that was designed to help pelvic health professionals stay healthy and inspired while equipping therapists with new tools to share with their patients.

We hope you will join us for Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation this November 9-11, 2019 in San Diego, CA.

Look forward to my next blog where The Rescuer (me) needs Rescuing and learn about the Drama Triangle.

Remshardt, Mary Ann EdD, MSN, RN "Do you know your professional boundaries?" Nursing Made Incredibly Easy!: January/February 2012 - Volume 10 - Issue 1 - p 5–6 doi: 10.1097/01.NME.0000406039.61410.a5

Diagnosing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction can be tricky. Therapists need to rule out lumbar spine and the hip, and sometimes there is more than one area causing pain and limiting functional mobility. Typically, ruling in SIJ dysfunction is done by pain provocation tests and load transfer tests. Once the SIJ has been ruled in, then therapists can use a variety of treatments. Often those treatments include therapeutic exercise, joint manipulation, and Kinesio tape. But which intervention is the most effective?

A recent study looked at three physical therapy interventions for treatment for SIJ (sacroiliac joint) dysfunction and assessed which was the most effective (Al-Subahi, M 2017). The authors did a systematic review of the literature. The articles were from 2004-2014, written in English, with male and female participants. This review included a variety of experiment types from randomized control trials to case studies. Of the 1114 studies, only 9 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Four of the nine studies used manipulation, three used Kinesio Tape, and the three used exercise. One study did both exercise and manipulation, and was looked at in both interventions. All categories had at least one randomized control trial.

For the manipulation intervention, all studies showed a decrease in pain and disability at follow up. The follow ranged from 3 to 4 days to 8 weeks. Disability was measured using the Oswestry Disability Index. One study did manual high velocity and low amplitude thrust manipulation to lumbar and SIJ manipulation and showed improvement with manipulation to SIJ or SIJ and lumbar. The review did not disclose the type of lumbar manipulation, but did state the SIJ manipulation was a side bend and rotation position with an inferior and lateral force to ASIS (anterior superior iliac spine). Another study did either a SIJ manual high velocity and low amplitude thrust manipulation or a mechanical force with manual assistance. One studied did manipulation and home exercises but did not record exercise interventions. The last study did the same SIJ manual high velocity and low amplitude thrust manipulation as in previous study combined with exercise. The exercises are mentioned below.

For the exercise intervention, the studies did primarily stabilization exercises that were either isometric or isotonic eccentric or concentric. Quick PT school review, in isometric exercises the muscle does not change length, while in isotonic eccentric exercises the muscle is being lengthened under load, and isotonic concentric is the muscle shortening under load. All three studies showed decrease in pain. The first study had 7 participants and combined manipulation and exercise. The exercises consisted of 12% max voluntary contraction and eccentric loading quads in supine with hips at 90 degrees, and concentrically loading hamstrings in prone. The second study was a case study and performed 8 lumbo-pelvic-femoral stabilization exercises for 8 weeks. Fun fact: this case study was written by my Therapeutic Exercise teacher in PT school who did a lot of Postural Restoration based exercises. The last study, had 22 participants and educated and provided exercises on deep abdominal and multifidus muscles and do complete these exercises during functional movements throughout the day. These participants were follow up a year later and had decreased pain compared to laser group.

For the Kinesio tape (Kinesio tape) intervention, the studies did not find that Kinesio tape was not an effective intervention, however the follow up ranged from immediately after applying tape to 4 weeks afterwards. In the first study, a randomized controlled trial with 60 participants, the Kinesio tape was applied in sitting with 25% tension of 4 strips making a star pattern over the point of maximal pain. The Kinesio tape was compared to placebo tape and showed equal improvement in pain and disability. The other two studies applied a different taping technique where the Kinesio tape was applied. One applied the tape over erector spinae and internal oblique muscles bilaterally and in the other study the Kinesio tape was applied with 25% tension over external obliques, a second strip was placed from ASIS to PSIS in side-lying, and then a third strip was placed along rectus abdominis muscle. In this same study the tape was applied for weeks (6x/week for 9 hours/day).

In summary, the authors note that all three interventions help decrease pain and disability in women and men with SIJ dysfunction. The authors suggest that manipulation may be the most effective. Kinesio tape showed no significant difference between placebo tape. Exercise was effective, but less so than manipulation.

This review has a lot of limitations. The variety of experiment types with varying degrees of evidence, small number of participants, and lack of blinding. Most studies had a limited follow up ranging from 3-4 days to 12 months. The outcome measures varied greatly. Most studies had pain scores as the outcome measure, though one study only used inclination meter of anterior pelvic tilt. Use of a consistent objective measure in addition to perceived pain and disability would have helped. Only 1 study did pain provocation tests and that study was a case study whose intervention focused on Kinesio-taping.

As physical therapists we want to provide effective evidence-based practice, and we want to provide individualized compassionate care. It is hard to make a direct line between this study’s recommendations and clinical application based on the numerous limitations. I agree with the authors that manipulation and exercise are bread and butter to physical therapists. I disagree about Kinesio tape not being an effective treatment. Is Kinesio tape going to create boney alignment changes? Likely not. Is Kinesio tape (or any other tape) going to give proprioceptive feedback and possibly help calm sensory pathways? Yes. If a patient likes being taped, and thinks it will help, then I will tape them. Even if taping is just placebo effect; it’s still an effect.

Al-Subahi, M., Alayat, M., Alshehr, M.A., et al. (2017) The effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for sacroiliac joint dysfunction: A systematic review. J Phys. Ther. Sci. 29: 1689-1694.