In a previous post on The Pelvic Rehab Report Sagira Vora, PT, MPT, WCS, PRPC shared that "cognitive-behavioral therapy appears to play a significant role in improving sexual function in women". Today, in part three of her ongoing series on sex and pelvic health, Sagira explores how sexual pain affects sexual dysfunction in women.

After having explored what allows for women to have pleasurable sexual experiences including pain-free sex and mind-blowing orgasms, we now turn towards our cohort that have pain with sex and intimacy. How does this group differ from women who do not have pain with sex? Are there some common factors with this group of women, and perhaps understanding these factors may help the pelvic floor therapist render more effective and successful treatment?

After having explored what allows for women to have pleasurable sexual experiences including pain-free sex and mind-blowing orgasms, we now turn towards our cohort that have pain with sex and intimacy. How does this group differ from women who do not have pain with sex? Are there some common factors with this group of women, and perhaps understanding these factors may help the pelvic floor therapist render more effective and successful treatment?

There are few studies exploring sexual arousal in women with sexual pain disorders. However, their findings are remarkable. Brauer and colleagues found that genital response, as measured by vaginal photoplethysmography and subjective reports, was found to be equal in women with sexual pain vs. women who did not have pain, when they were shown oral sex and intercourse movie clips. This and other studies have shown that genital response in women with dyspareunia is not impaired. Genital response in women with dyspareunia is however, effected by fear of pain. When Brauer and colleagues subjected women with dyspareunia to threat of electrical shock (not actual shock) while watching an erotic movie clip they found that women with dyspareunia had much diminished sexual response including diminished genital arousal. But Spano and Lamont found that genital response was diminished by fear of pain equally in women with sexual pain and women without sexual pain.

Fear of pain also resulted in increased muscle activity in the pelvic floor. However, this increase was noted in women with pain and women without sexual pain equally and was noted with exposure to sexually threatening film clips as well as threatening film clips without sexual content. The conclusion, then, from these results is that the pelvic floor plays a role in emotional processing and tightening, or overactivity is a protective response noted in all women regardless of sexual pain history.

The one difference that was noted was with women who had the experience of sexual abuse. For them, pelvic floor overactivity was noted when watching sexually threatening as well consensual sexual content. Women without sexual abuse history did not have increased pelvic floor activity when watching consensual sexual content.

In summary, evidence supports the hypothesis that women with sexually adverse experiences tend to have impaired genital response when in consensual sexual situations, however, women who do not have sexual abuse histories and but have sexual pain tend to have appropriate genital response. Both groups, however, have increased pelvic floor muscle activity in consensual sexual situations. This increase in pelvic floor muscle activity leads to muscle pain, reduced blood flow, reduced lubrication, increased friction between penis and vulvar skin and hence leads to pain.

This brings us to our next questions, how does the cohort that has had adverse sexual experiences present? How do women with history of sexual trauma process sexual experiences? How does the pelvic floor present or respond to consensual sexual situations when a woman has been abused in the past? Please tune in to the next blog for answers…

Blok BF, Holstege G. The neuronal control of micturition and its relation to the emotional motor system. Prog Brain Res. 1996; 107:113-26

Brauer M, Laan E, ter Kuile MM. Sexual arousal in women with superficial dyspareunia. Arch Sex Behav. 2006; 35:191-200

Brauer M, ter Kuile MM, Janssen S, Lann E. The effect of pain-related fear on sexual arousal in women with superficial dyspareunia. Eur J Pain: 2007; 11:788-98

Spano L, Lamont JA. Dyspareunia: a symptom of female sexual dysfunction. Can Nurse 1975;71:22-5

In a previous post on The Pelvic Rehab Report, Sagira Vora, PT, MPT, WCS, PRPC explored the impact that pelvic floor exercises can have on arousal and orgasm in women. Today we hear part two of the conversation, and learn what factors can impact a woman's ability to achieve orgasm.

“An orgasm in the human female is a variable, transient peak sensation of intense pleasure, creating an altered state of consciousness, usually with an initiation accompanied by involuntary, rhythmic contractions of the pelvic striated circumvaginal musculature, often with concomitant uterine and anal contractions, and myotonia that resolves the sexually induced vasocongestion and myotonia, generally with an induction of well-being and contentment.”

“An orgasm in the human female is a variable, transient peak sensation of intense pleasure, creating an altered state of consciousness, usually with an initiation accompanied by involuntary, rhythmic contractions of the pelvic striated circumvaginal musculature, often with concomitant uterine and anal contractions, and myotonia that resolves the sexually induced vasocongestion and myotonia, generally with an induction of well-being and contentment.”

Wow, that sounds like paradise! The question is--how to get there? Many of our cohorts and many our female patients have not experienced this or orgasm happens for them rarely. Findings from surveys and clinical reports suggest that orgasm problems are the second most frequently reported sexual problems in women. Some of the reasons cited for lack of orgasm are orgasm importance, sexual desire, sexual self-esteem, and openness of sexual communication with partner by Kontula el. al. in 2016. Rowland found that most commonly-endorsed reasons were stress/anxiety, insufficient arousal, and lack of time during sex, body image, pain, inadequate lubrication.

One factor that comes up consistently, is the ability of women to focus on sexual stimuli. This point has been brought up by various studies and presented in different ways. Chambless talks about mindfulness training and improvements in orgasm ability noted equally in women who practiced mindfulness vs. women who engaged in Kegels and mindfulness. Rosenbaum and Padua note in their book, The Overactive Pelvic Floor, “women who do not have a low-tone pelvic floor and who seek to enhance sexual arousal and more frequent orgasms have not much to gain from pelvic floor muscle training. Actually, a relaxed pelvic floor and mindful attention to sexual stimuli and bodily sensations seem a more effective means of enhancing sexual arousal and orgasm.” Various studies specifically studying the effect of mindfulness training have demonstrated both improved arousal and orgasm ability in women who practiced mindfulness. Brotto and Basson found their treatment group, which consisted of 68 otherwise healthy women, who underwent mindful meditation, cognitive behavioral training and education, improved in sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, sexual satisfaction, and overall sexual functioning.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy appears to play a significant role in improving sexual function in women. Meston et. al. notes, “cognitive behavioral therapy for anorgasmia focuses on promoting changes in attitudes and sexually relevant thoughts, decreasing anxiety, and increasing orgasmic ability and satisfaction. To date there are no pharmacological agents proven to be beneficial beyond placebo in enhancing orgasmic function in women.”

Alas, there are no magic pills to create the above described “state of altered consciousness,” allowing women a sense of “well-being and contentment.” However, mindfulness training and cognitive behavioral therapy are both accessible and attainable for women who want to improve their ability to enjoy this much desired state. Many Pelvic floor therapist incorporate cognitive behavioral and mindfulness approaches in their practice.

The studies above mention pain as one of the factors for inability to experience arousal and orgasm. Hucker and Mccabe even noted that their mindfulness treatment group demonstrated significant improvements in all domains of female sexual response except for sexual pain. Dealing with sexual pain is a daily battle pelvic floor therapist face each day. So, how do women with sexual pain dysfunction differ from women who are experiencing sexual dysfunction but not pain? Let’s explore this in our next blog…

Chambless DL, Sultan FE, Stern TE, O’Neill C, Garrison S. Jackson A. Effect of pubococcygeal exercise on coital orgasm in women. J Consult CLin Psychol. 1984; 52:114-8

Bratto LA, Basson R. Group mindfulness-based therapy significantly improves sexual desire in women Behav Res Ther. 2014 Jun; 57:43-5

Hucker A. Mccabe MP. Incorporating Mindfulness and Chat Groups Into an Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Mixed Female Sexual Problems. J Sex Res. 2015;52(6):627-33

Kontula O., Mettienen A. Determinants of female sexual orgasms. Socioaffect Neurosci Psychol. 2016 Oct 25;6:31624. doi: 10.3402/snp.v6.31624. eCollection 2016

Meston CM1, Levin RJ, Sipski ML, Hull EM, Heiman JR. Women’s orgasm. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2004;15:173-257. Review

Rosenbaum, Talli Y., Padoa, Anna. The overactive Pelvic floor. 1st ed. 2016

Roland DL, Cempel LM, Tempel AR. Women’s attributions on why they have difficulty reaching orgasm. J. Marital Therapy. 2018 Jan 3:0

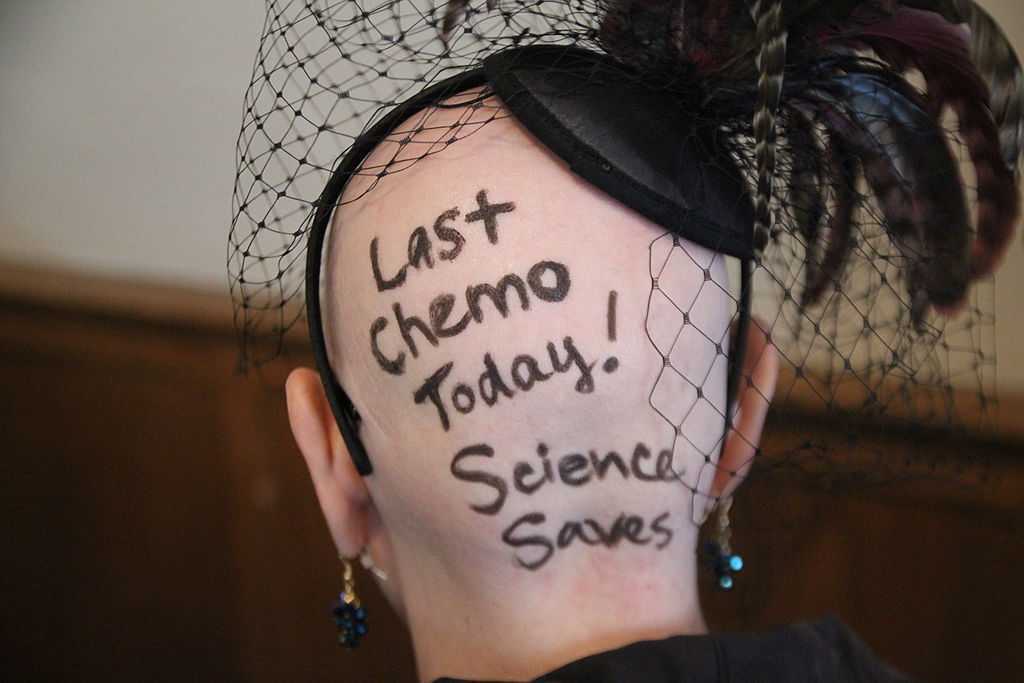

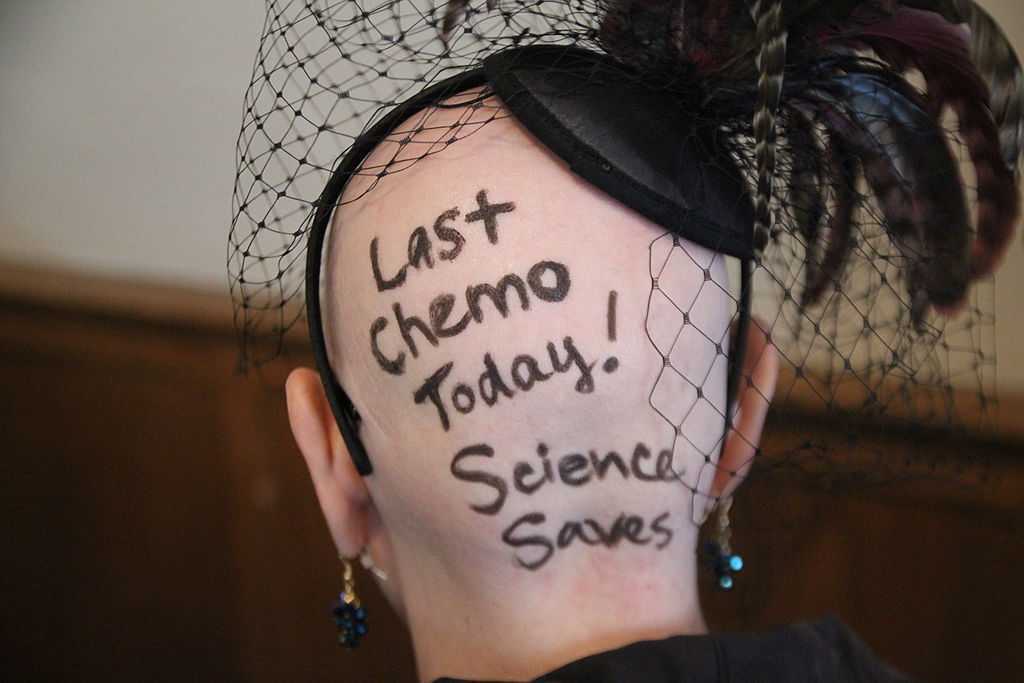

When a woman is given a cancer diagnosis, her entire world is turned upside down and inside out. There are so many things to think about; medical treatments, financial concerns, family concerns, and emotional upheaval. Sex may be the last thing that a woman may think about when she is actively going through treatment. However, at what rate are survivors having issues after treatment is complete?

A recent study published in the journal Cancer looked at just this. A 2-year longitudinal study was performed that tracked young adults (18-39 years old) through and after their cancer diagnosis. The most common cancers seen in the samples were leukemia, breast cancer, soft-tissue sarcoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The patients completed the Medical Outcomes Study Sexual Functioning Scale at 4 months, 6 months, and 24 months after diagnosis. At 2 years after diagnosis over 50% of the patients surveyed reported some degree of sexual dysfunction. Women that were in a committed relationship had an increased likelihood for experiencing sexual dysfunction; while men had increased rate of reporting sexual issues regardless of their relationship status.

A recent study published in the journal Cancer looked at just this. A 2-year longitudinal study was performed that tracked young adults (18-39 years old) through and after their cancer diagnosis. The most common cancers seen in the samples were leukemia, breast cancer, soft-tissue sarcoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The patients completed the Medical Outcomes Study Sexual Functioning Scale at 4 months, 6 months, and 24 months after diagnosis. At 2 years after diagnosis over 50% of the patients surveyed reported some degree of sexual dysfunction. Women that were in a committed relationship had an increased likelihood for experiencing sexual dysfunction; while men had increased rate of reporting sexual issues regardless of their relationship status.

Women that undergo cancer treatment have several reasons that could be influencing their sexual function. Fatigue is a complaint that is often expressed by cancer patients. Their body image is often altered due to surgeries that have been performed. Chemotherapy and hormonal therapy often push women into menopause which then leads to vaginal dryness. Additionally, radiation and surgical treatment can lead to scar tissue, fibrosis, and stenosis of the vagina and pelvic floor muscles.

This is where physical therapy can help! In the Pelvic Floor Series Capstone course we teach advanced techniques that help treat pelvic floor issues by working on both the muscles, and the fascia. We also cover techniques that decrease the tenderness in the muscles that then allow you to stretch the muscle with less discomfort.

All of the techniques taught in Capstone are gentle but effective. The cancer survivor is the perfect population to use these gentle techniques on! Think of how rewarding our job will be when we help relieve the pain that may be associated with intercourse, and therefore improve intimacy of a cancer survivor with her partner!

Come join us for Capstone and learn techniques that will take your treatment skills to the next level!

Acquati, Zebrack, Faul, et al. Sexual functioning among young adult cancer patients: A 2-year longitudinal study. Cancer. 2018; 124(2): 398-405.

Neurophysiology is a dynamic and highly complex system of neurological connections and interactions that allow for bodily performance. When all of those connections are working correctly, our bodies can function at optimal levels. When there is a break or injury to those connections, dysfunction results but amazingly in some circumstances, our bodies have work arounds to allow for certain functions to continue working.

If we take the sexual neural control system of the male, for instance, a perfect example of this can be described. Many men were injured fighting in World War II. During their time in battle, many experienced spinal cord injuries. Some of these injuries were severe resulting in complete spinal cord damage at level of injury. A physician, Herbert Talbot, in 1949, documented his examination of 200 men with paraplegia. Two thirds of the men were surprisingly able to achieve erections and some were able to experience vaginal penetration and orgasm. Much of their basic functionality had been lost however amazingly there was preservation of erectile function.

The reason these men with paraplegia were able to maintain erectile or orgasm functionality is due to the physiological function in the sacral spinal cord. A reflex arc is present in this region. The definition of a reflex arc is a nerve pathway that has a reflexive action involving sensory input from a peripheral somatic or autonomic nerve synapsing to a relay neuron or interneuron in the sacral cord segment then synapsing to a motor nerve for output to the muscular region. These messages do not need to travel up the spinal cord to the brain in order to be activated. Instead they work within a ‘loop’ at the sacral spinal cord level. In the case of spinal cord injury, erectile function as well as other functions controlled by reflex arcs, can be preserved.

For women, the same is true. In order for a female to have engorgement of the clitoris or orgasm, the sacral spinal reflex arc needs to be intact. If a woman experiences a spinal cord injury above the sacral region, the ability to have a reflexive orgasm within the sacral spinal reflex arc will remain.

The sacral reflex arc also plays an important role in activation of the pelvic floor muscles during the sexual response cycle. During genital stimulation in both the male and female, the bulbospongiosus or bulbocavernosus begins to activate in a reflexive pattern to hinder the outflow of blood from the region which facilitates erectile tissue of the penis and clitoris to become erect. This can then be followed by rhythmic reflexive contractions of the pelvic floor musculature during orgasm.

To learn more about the implications that neurologic disorders can have on the sexual system, please join us for Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab, coming to Grand Rapids, MI in September.

Goldstein, I. (2000). Male sexual circuitry. Scientific American, 283(2), 70-75.

Sipski, M. L. (2001). Sexual response in women with spinal cord injury: neurologic pathways and recommendations for the use of electrical stimulation. The journal of spinal cord medicine, 24(3), 155-158.

Wald, A. (2012). Neuromuscular Physiology of the Pelvic Floor. In Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract (Fifth Edition)(pp. 1023-1040).

Sagira Vora, PT, MPT, WCS, PRPC practices in Bellevue, WA at the Overlake Hospital Medical Center, and she played a pivotal role in creating the Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification examination. Today's post is part one of a multi-part series on pelvic rehabilitation and sexual health. Stay tuned for part two!

“Have mind-blowing sex: learn how to do your Kegels.” “Amazing orgasms, ladies do your Kegels!” These were just some of the headlines that greeted me as I researched what was being said in the popular media regarding pelvic floor exercises and improving sexual function in women. Some other wisdom from popular women’s magazines included advice on, “stopping the flow of urine,” to do your Kegels. We know how much we pelvic floor therapists love hearing that phrase!

I found a few recent and past studies that have tried to study pelvic floor exercises and sexual function in women.

In 1984, Chambless et.al. studied a small group of women who were able to achieve orgasm through intercourse less than 30% of time. Strength gains in the pubococcygeus muscles were noted in the exercise group but neither the exercise nor control group achieved increased orgasmic frequency.

In a more recent study, Lara et. al. studied 32 sexually active post-menopausal women, who had the ability to contract their pelvic floor muscles, tested the hypothesis that 3 months of physical exercises including pelvic floor muscle training with biweekly physical therapy visits and exercise performed at home three times a week, would enhance sexual function. Pelvic floor muscle strength was significantly improved post-test, but this study found no effect on sexual function.

Forty years after Dr. Kegel’s assertion about sexual arousal enhancing properties of pubococcygeus muscle exercises, Messe and Geer tested Kegel’s hypothesis in their psychophysiological study, in which they asked women to perform vaginal contractions while engaging in sexual fantasy. A second group was asked to engage in sexual fantasy without the contractions, and yet a third group was given the task of vaginal contractions but no sexual fantasy. The results indicated that performing vaginal contractions with sexual fantasy improved arousal and orgasmic ability. Initially, this group made better gains than vaginal contractions alone and fantasizing alone. However, with a second test session one week later, no further gains were noted in the ability of this group to improve sexual arousal or orgasm. Messe and Geer speculated that increased muscle tone may result in increased stimulation of stretch and pressure receptors during intercourse, leading to enhanced arousal and orgasmic potential.

The most interesting finding was reported by an older study done by Roughan, who reported no differences in the groups he studied. Roughan et. al. expected women with orgasm difficulties to improve after 12-week period of pelvic floor strengthening exercises, compared to a group that practiced relaxation and an attention control group. No difference was found between the orgasmic ability of the two groups.

The majority of women studied here had no reported pelvic floor dysfunction. Perhaps, contrary to popular opinion and against the advice of women’s magazines, women with healthy pelvic floors may not benefit from pelvic floor exercises any more than they would from relaxation training, or mindful attention to sexual stimuli.

So, what then, will increase our mojo in bed, you ask? Stay tuned for the next blogs…

Chambless D, Sultan FE, Stern TE, O’Neill C, Garrison S. Jackson A. Effect of pubococcygeal exercise on coital orgasm in women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984; 52:114-8

Laan E. Rellini AH. Can we treat anorgasmia in women? The challenge to experiencing pleasure: Sex Relation Ther. 2011:26:329-41

Messe MR, Geer JH. Voluntary vaginal musculature contractions as an enhancer of sexual arousal. Arch Sex Behav. 1985; 14:13-28

Padoa, Anna. Rosenbaum, Talli. 1st edition. 2016. The Overactive Pelvic Floor.

Roughan PA, Kunst L. Do pelvic floor exercises really improve orgasmic potential? J Sex Marital Ther. 1984;7:223-9

The following is the first in a series of posts by Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC. Erica joined the Herman & Wallace faculty in 2018 and is the author of Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab.

Looking back, being passionate about how to physically exercise a person with Parkinson disease to produce the best functional outcome actually became a passion of mine when I was offered my first job. I was thrown into treating people with Parkinson disease in an acute care setting. I had very limited knowledge about Parkinson disease at the time, but I learned quickly from the vast opportunity that was offered to me through my place of work, which was the regions sought after Parkinson disease center of excellence. At the same time, I was eager to further advance my skills as a pelvic floor therapist, which I developed a substantial interest in when I was in college.

As I learned more about what people with Parkinson disease had to manage in their daily lives, it became very clear to me that autonomic dysfunction was a very challenging, and sometimes disabling, aspect of the disease. Being knowledgeable about the neurological and musculoskeletal system along with the urinary, gastrointestinal, and sexual systems seemed to fit well together but there was no specific place to go to combine this knowledge. The research I began collecting on this topic was abundant and very intriguing. Bringing this information together could be practice changing for me to help people living with Parkinson disease.

As clinicians, we already know how to be understanding about the very personal details of the people we work with. People with Parkinson disease deal with an extra layer of challenge, such as, bradykinesia, freezing of gait, and tremor affecting their day to day self-care and relationships. Adding urinary incontinence, constipation or sexual dysfunction to the list makes for even more difficult management.

How does one clinician share their passion with other clinicians that also have the same desires to give the best care to their patients with Parkinson disease? Having a great deal of respect for Herman and Wallace and what they have to offer clinicians practicing pelvic rehabilitation, it seemed like it could be the perfect fit for a course like this. The work that would lie ahead if this idea took off was overwhelming but did not hinder me from my proposal. In fact, it has led to an even larger scope addressing the of treatment of the pelvic floor for a multitude of neurologic conditions many of us see daily in our clinics. Pulling it all together to share is a process that will reward not only people with Parkinson disease in my practice but hopefully yours as well.

It’s St Valentine’s day this week – you may have noticed hearts and flowers everywhere you look and a general theme of love and romance. For many women going through cancer treatment, sex may be the last thing on their mind…or not! Women who are going through treatment for gynecologic cancer are often handed a set of dilators with minimal instruction on how to use them, or as one patient reported, they are told to have sex three or four times a week during radiation therapy ‘to keep your vagina patent’. As a pelvic rehab practitioner with a special interest in oncology rehab, I know that we can (we must!) do better, in helping women live well after cancer treatment ends.

As Susan Gubar, an ovarian cancer survivor, writes in the New York Times ‘…It can be difficult to experience desire if you don’t love but fear your body or if you cannot recognize it as your own. Surgical scars, lost body parts and hair, chemically induced fatigue, radiological burns, nausea, hormone-blocking medications, numbness from neuropathies, weight gain or loss, and anxiety hardly function as aphrodisiacs…’

As Susan Gubar, an ovarian cancer survivor, writes in the New York Times ‘…It can be difficult to experience desire if you don’t love but fear your body or if you cannot recognize it as your own. Surgical scars, lost body parts and hair, chemically induced fatigue, radiological burns, nausea, hormone-blocking medications, numbness from neuropathies, weight gain or loss, and anxiety hardly function as aphrodisiacs…’

Although sexual changes can be categorised into physical, psychological and social, the categories cannot be neatly delineated in the lived experience (Malone at al 2017). The good news? Pelvic rehab therapists not only have the skills to enhance pelvic health after cancer treatment and are ideally positioned to be able to take a global and local approach to the sexual health difficulties women may face after cancer treatment ends, but there is also a good and growing body of evidence to support the work we do. Factors to consider include physical issues leading to dyspareunia, including musculo-skeletal/ orthopaedic, Psychological issues, including loss of libido and other pelvic health issues impacting sexual function such as faecal/ urinary incontinence, pain or fatigue.

In Hazewinkel’s 2010 paper, women reported that they thought their physicians would tell them if solutions were available…most reported reasons for not seeking help were that women found their symptoms bearable in the light of their cancer diagnosis and lacked knowledge about possible treatments but when informed of possible treatment strategies ‘…women stated that care should be improved, specifically by timely referral to pelvic floor specialists’. The good news: ‘‘Pelvic Floor Rehab Physiotherapy is effective even in gynecological cancer survivors who need it most.’ (Yang 2012)

The issue therefore may be one of awareness – for both the women who need our services and the physicians and healthcare team who work in the field of gynecologic oncology. What we need is acknowledgement of the issues and confident conversation and assessment by clinicians – interested in learning more? Come and join the conversation in Tampa next month at my Oncology & the Female Pelvic Floor course!

‘Sex after Cancer’ by Susan Gubar, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/18/well/live/sex-after-cancer.html

Malone et al 2017: ‘‘The patient’s voice: What are the views of women on living with pelvic floor problems following successful treatment for pelvic cancers?’

Hazewinkel et al 2010 ‘Reasons for not seeking medical help for severe pelvic floor symptoms: a qualitative study in survivors of gynaecological cancer’

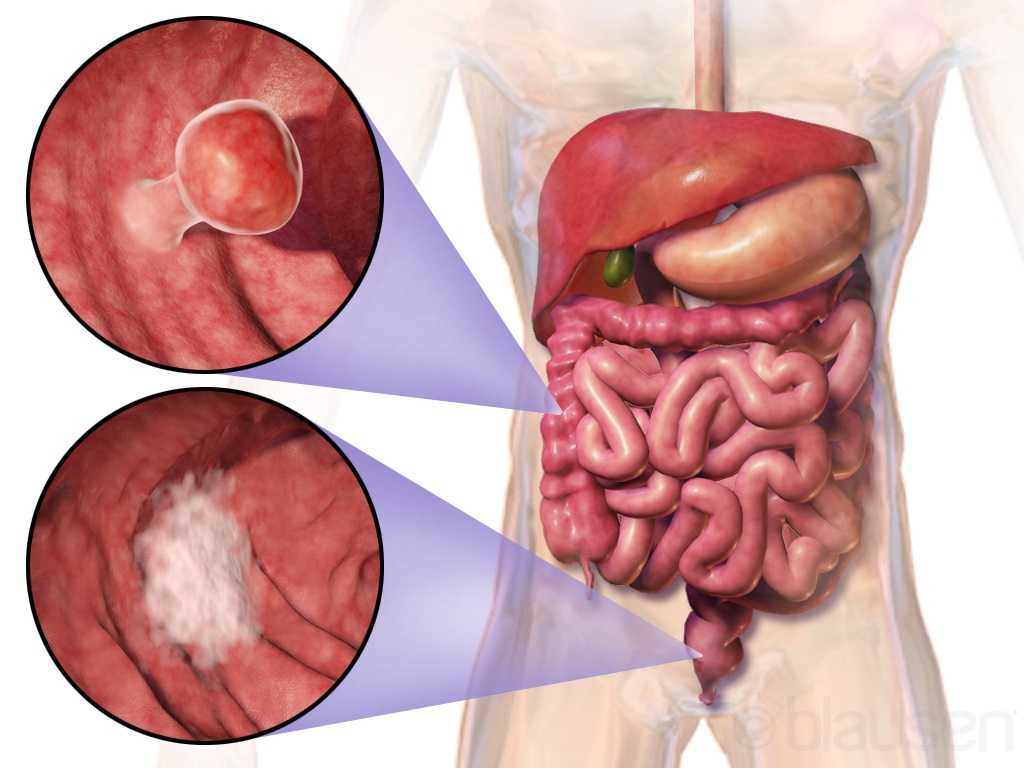

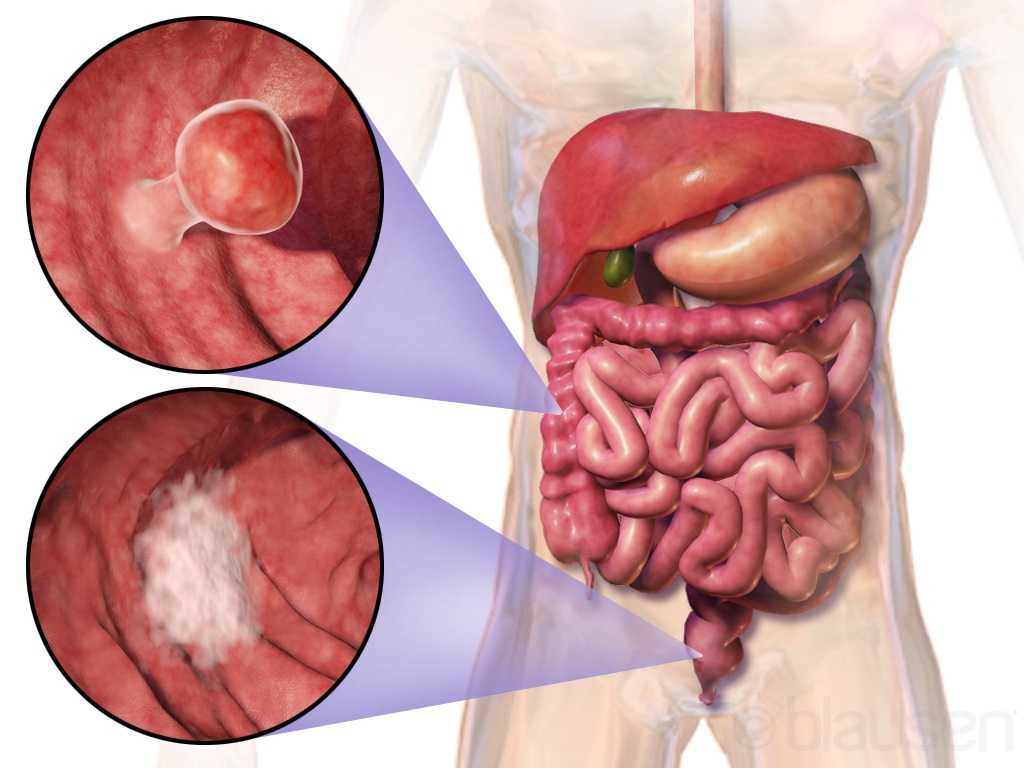

Curing cancer but not addressing life-altering complications can be compared to feeding the homeless on Thanksgiving but turning your back on them the rest of the year. We love hearing positive outcomes of a surgery, but we are not always aware of what happens beyond that. Colorectal cancer is often treated by colectomy, and sometimes the survivor of cancer is left with urological or sexual dysfunction, small bowel obstruction, or pelvic lymphedema.

Panteleimonitis et al., (2017) recognized the prevalence of urological and sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery and compared robotic versus laparoscopic approaches to see how each impacted urogenital function. In this study, 49 males and 29 females underwent laparoscopic surgery, and 35 males and 13 females underwent robotic surgery. Prior to surgery, 36 men and 9 women were sexually active in the first group and 13 men and 4 women were sexually active in the latter group. Focusing on the male results, male urological function (MUF) scores were worse pre-operatively in the robotic group for frequency, nocturia, and urgency compared to the laparoscopic group. Post-operatively, urological function scores improved in all areas except initiation/straining for the robotic group; however, the MUF median scores declined in the laparoscopic group. Regarding male sexual function (MSF) scores for libido, erection, stiffness for penetration and orgasm/ ejaculation, the mean scores worsened in all areas for the laparoscopic group but showed positive outcomes for the robotic group. In spite of limitations of the study, the authors concluded robotic rectal cancer surgery may afford males and females more promising urological and sexual outcomes as robotic.

Panteleimonitis et al., (2017) recognized the prevalence of urological and sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery and compared robotic versus laparoscopic approaches to see how each impacted urogenital function. In this study, 49 males and 29 females underwent laparoscopic surgery, and 35 males and 13 females underwent robotic surgery. Prior to surgery, 36 men and 9 women were sexually active in the first group and 13 men and 4 women were sexually active in the latter group. Focusing on the male results, male urological function (MUF) scores were worse pre-operatively in the robotic group for frequency, nocturia, and urgency compared to the laparoscopic group. Post-operatively, urological function scores improved in all areas except initiation/straining for the robotic group; however, the MUF median scores declined in the laparoscopic group. Regarding male sexual function (MSF) scores for libido, erection, stiffness for penetration and orgasm/ ejaculation, the mean scores worsened in all areas for the laparoscopic group but showed positive outcomes for the robotic group. In spite of limitations of the study, the authors concluded robotic rectal cancer surgery may afford males and females more promising urological and sexual outcomes as robotic.

Husarić et al., (2016) considered the risk factors for adhesive small bowel obstruction (SBO) after colorectal cancer colectomy, as SBO is a common morbidity that causes a decrease in quality of life. They performed a retrospective study of 248 patients who underwent colon cancer surgery, and 13.7% of all the patients had SBO. Thirty (14%) of the 213 males and 9 (12.7%) of the 71 females had SBO; consequently, they found patients being >60 years old was a more significant risk factor than sex regarding occurrence of SBO. The authors concluded a Tumor-Node Metastasis stage of >3 and immediate postoperative complications were found to be the greatest risk factors for SBO.

Vannelli et al., (2013) explored the prevalence of pelvic lymphedema after lymphadenectomy in patients treated surgically for rectal cancer. Five males and 8 females were examined one week before and 12 months after being discharged from the hospital. All 9 of the patients (4 males, 5 females) with extra-peritoneal cancer exhibited lymphedema via MRI, but the 4 (1 male, 3 females) patients with intra-peritoneal cancer had none. The authors concluded pelvic lymphedema can be elusive after rectal surgery, but pelvic disorders persist and patients should be routinely examined for it.

Obviously saving a life is the primary goal when it comes to cancer. But just like caring for the destitute for one day doesn’t cure a lifetime of hunger, ignoring the negative post-surgical sequelae of a colectomy prevents a cancer survivor from living a healthy life. Herman & Wallace offers two pelvic floor oncology courses, “Oncology and the Male Pelvic Floor” and "Oncology and the Female Pelvic Floor" , which address how pelvic cancers affect the quality of life of our patients and how practitioners can make a positive impact.

Panteleimonitis, S., Ahmed, J., Ramachandra, M., Farooq, M., Harper, M., & Parvaiz, A. (2017). Urogenital function in robotic vs laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery: a comparative study. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 32(2), 241–248. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-016-2682-7

Husarić E., Hasukić Š, Hotić N, Halilbašić A, Husarić S, Hasukić I. (2016). Risk factors for post-colectomy adhesive small bowel obstruction. Acta

When I work prn in inpatient rehabilitation, I have access to each patient’s chart and can really focus on the systems review and past medical history, which often gives me ample reasons to ask about pelvic floor dysfunction. So, of course, I do. I have yet to find a gynecological cancer survivor who does not report an ongoing struggle with urinary incontinence. And sadly, they all report that they just deal with it.

Bretschneider et al.2016 researched the presence of pelvic floor disorders in females with presumed gynecological malignancy prior to surgical intervention. Baseline assessments were completed by 152 of the 186 women scheduled for surgery. The rate of urinary incontinence (UI) at baseline was 40.9% for the subjects, all of whom had uterine, ovarian, or cervical cancer. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) was reported by 33.3% of the women, urge incontinence (UI) by 25%, fecal incontinence (FI) by 3.9%, abdominal pain by 47.4%, constipation by 37.7%, and diarrhea by 20.1%. The authors concluded pelvic floor disorders are prevalent among women with suspected gynecologic cancer and should be noted prior to surgery in order to provide more thorough rehabilitation for these women post-operatively.

Bretschneider et al.2016 researched the presence of pelvic floor disorders in females with presumed gynecological malignancy prior to surgical intervention. Baseline assessments were completed by 152 of the 186 women scheduled for surgery. The rate of urinary incontinence (UI) at baseline was 40.9% for the subjects, all of whom had uterine, ovarian, or cervical cancer. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) was reported by 33.3% of the women, urge incontinence (UI) by 25%, fecal incontinence (FI) by 3.9%, abdominal pain by 47.4%, constipation by 37.7%, and diarrhea by 20.1%. The authors concluded pelvic floor disorders are prevalent among women with suspected gynecologic cancer and should be noted prior to surgery in order to provide more thorough rehabilitation for these women post-operatively.

Ramaseshan et al.2017 performed a systematic review of 31 articles to study pelvic floor disorder prevalence among women with gynecologic malignant cancers. Before treatment of cervical cancer, the prevalence of SUI was 24-29% (4-76% post-treatment), UI was 8-18% (4-59% post-treatment), and FI was 6% (2-34% post- treatment). Cervical cancer treatment also caused urinary retention (0.4-39%), fecal urge (3-49%), dyspareunia (12-58%), and vaginal dryness (15-47%). Uterine cancer showed a pre-treatment prevalence of SUI (29-36%), UUI (15-25%), and FI (3%) and post-treatment prevalence of UI (2-44%) and dyspareunia (7-39%). Vulvar cancer survivors had post-treatment prevalence of UI (4-32%), SUI (6-20%), and FI (1-20%). Ovarian cancer survivors had prevalence of SUI (32-42%), UUI (15-39%), prolapse (17%) and sexual dysfunction (62-75%). The authors concluded pelvic floor dysfunction is prevalent among gynecologic cancer survivors and needs to be addressed.

Lindgren, Dunberger, & Enblom2017 explored how gynecological cancer survivors (GCS) relate their incontinence to quality of life, view their physical activity/exercise ability, and perceive pelvic floor muscle training. The authors used a qualitative interview content analysis study with 13 women, age 48–82. Ten women had UI and 3 had FI after treatment (2 had radiation therapy, 5 had surgery, and 6 had surgery as well as radiation therapy). The results showed a reduction in physical and psychological quality of life and sexual activity because of incontinence. Having minimal to no experience or even awareness of pelvic floor training, 9 out of the 10 women were willing to spend 7 hours a week to improve their incontinence. Practical and emotional coping strategies also helped these women, and they all declared they had the cancer treatments without being informed of the risk of incontinence, which impacted their attitude and means of handling the situation.

Research shows incontinence is a common occurrence after gynecological cancer treatment. It impacts quality of life after surviving a serious illness, and many women do not know pelvic floor therapy can improve their situation. Oncology and the Female Pelvic Floor is an ideal course for practitioners to take to help increase their knowledge on how to educate and treat this population.

Bretschneider, C. E., Doll, K. M., Bensen, J. T., Gehrig, P. A., Wu, J. M., & Geller, E. J. (2016). Prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in women with suspected gynecological malignancy: a survey-based study. International Urogynecology Journal, 27(9), 1409–1414. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-2962-3

Ramaseshan, A.S., Felton, J., Roque, D., Rao, G., Shipper, A.G., Sanses, T.V.D. (2017). Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: a systematic review. International Urogynecology Journal. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3467-4

Lindgren, A., Dunberger, G., & Enblom, A. (2017). Experiences of incontinence and pelvic floor muscle training after gynaecologic cancer treatment. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(1), 157–166. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3394-9

As I read about male phimosis, I thought about a shirt that just won’t go over my son’s big noggin. I tug and pull, and he screams as his blond locks stick up from static electricity. Ultimately, if I want this shirt to be worn, I either have to cut it or provide a prolonged stretch to the material, or my child will suffocate in a polyester sheath. This is remotely similar to the male with physiological phimosis.

In a review article, Chan and Wong (2016) described urological problems among children, including phimosis. They reported “physiological phimosis” is when the prepuce cannot be retracted because of a natural adhesion to the glans. Almost all normal male babies are born with a foreskin that does not retract, and it becomes retractable in 90% of boys once they are 3 years old. A biological process occurs, and the prepuce becomes retractable. In “pathological phimosis” or balanitis xerotica obliterans, the prepuce, glans, and sometimes even the urethra experience a progressive inflammatory condition involving inflammation of the glans penis, an unusually dry lesion, and occasional endarteritis. Etiology is unknown, but males by their 15th birthday report a 0.6% incidence, and the clinical characteristics include a white tip of the foreskin with a ring of hard tissue, white patches covering the glans, sclerotic changes around the meatus, meatal stenosis, and sometimes urethral narrowing and urine retention.

In a review article, Chan and Wong (2016) described urological problems among children, including phimosis. They reported “physiological phimosis” is when the prepuce cannot be retracted because of a natural adhesion to the glans. Almost all normal male babies are born with a foreskin that does not retract, and it becomes retractable in 90% of boys once they are 3 years old. A biological process occurs, and the prepuce becomes retractable. In “pathological phimosis” or balanitis xerotica obliterans, the prepuce, glans, and sometimes even the urethra experience a progressive inflammatory condition involving inflammation of the glans penis, an unusually dry lesion, and occasional endarteritis. Etiology is unknown, but males by their 15th birthday report a 0.6% incidence, and the clinical characteristics include a white tip of the foreskin with a ring of hard tissue, white patches covering the glans, sclerotic changes around the meatus, meatal stenosis, and sometimes urethral narrowing and urine retention.

This review article continues to discuss the appropriate treatment for phimosis (Chan & Wong 2016). Once phimosis is diagnosed, the parents of the young male need to be educated on keeping the prepuce clean. This involves retracting the prepuce gently and rinsing it with warm water daily to prevent infection. Parents are warned against forcibly retracting the prepuce. A study has shown complete resolution of the phimosis occurred in 76% of boys by simply stretching the prepuce daily for 3 months. Topical steroids have also been used effectively, resolving phimosis 68.2% to 95%. Circumcision is a surgical procedure removing foreskin to allow a non-covered glans. Jewish and Muslim boys undergo this procedure routinely, and >50% of US boys get circumcised at birth. Medical indications are penile malignancy, traumatic foreskin injury, recurrent attacks of severe balanoposthitis (inflammation of the glans and foreskin), and recurrent urinary tract infections.

Pedersini et al., (2017) evaluated the functional and cosmetic outcomes of “trident” preputial plasty using a modified-triple incision for surgically managing phimosis in children ages 3-15. All patients seen in a 1 year period who were unable to retract the foreskin and had posthitis or balanoposthitis or ballooning of the foreskin during urination were included and treated initially with a two-month trial of topic corticosteroids. Only the patients unresponsive to corticosteroids were treated with the "trident" preputial plasty. At 12 months post-surgery, 97.6% (all but one of the 41 subjects) of patients were able to retract the prepuce, and cosmetics and function were satisfactorily restored.

Phimosis is apparently not a highlight in medical school curriculum, and parents often seek attention for other issues that lead to the diagnosis of phimosis. Like the tight material lining the neck of a shirt, the prepuce can be given a prolonged static stretch, and, over time, may retract appropriately. Or, cutting the shirt material may be necessary for long term success. Similarly, surgical intervention such as circumcision or the newer “trident” preputial plasty may be required.

Chan, Ivy HY and Wong, Kenneth KY. (2016). Common urological problems in children: prepuce, phimosis, and buried penis. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 22(3):263–9. DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154645

Pedersini, P, Parolini, F, Bulotta, AL, Alberti, D. (2017). "Trident" preputial plasty for phimosis in childhood. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 13(3):278.e1-278.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.01.024