Pain demands an answer. Treating persistent pain is a challenge for everyone; providers and patients. Pain neuroscience has changed drastically since I was in physical therapy school. This update comes from the International Spine and Pain Institute headed by the lead author Adriaan Louw, PT, PhD. If you are interested in reading more about persistent pain, I suggest reading the article in its entirety.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

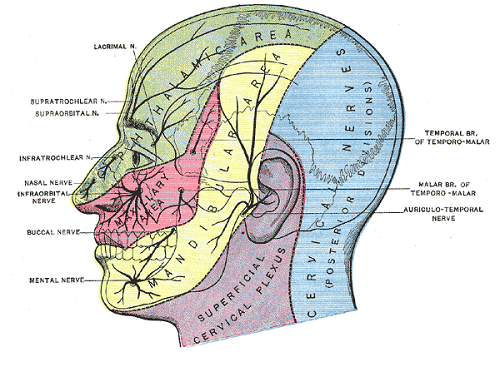

Pain neuroscience education is a way to explain pain to patients, often with analogies, with a focus on neurobiology and neurophysiology as it relates to that individuals pain experience. To be able to educate our patients, we as providers, must be able to understand neuromatrix, output, and threat. Moseley states “[p]ain is a multiple system output activated by an individual’s specific pain neuromatrix. The neuromatrix is activated whenever the brain perceives a threat”. If that sounds like gibberish, consider watching this TEDx talk by Lorimer Moseley on YouTube (the snake bite story is a favorite of mine):

What is a neuromatrix? Essentially, it is a pain map in the brain; a network of neurons spread throughout the brain, none of which deal specifically with pain processing. The way I visualize it is to think about what goes on when you think of your grandmother. There isn’t a grandmother center in the brain, but there are sights and smells (sensory), feelings (emotional awareness), and memories that all come up when you think about her. When we are overwhelmed with pain, those regions become taxed and the individual may have difficulty concentrating, sleeping, and/or may lose his/her temper more easily. Just as each person’s grandmother is different so is a person’s pain and the neuromatrix is affected by past experiences and beliefs.

Pain is an output. It is a response to a threat. When a person is exposed to a threatening situation, biological systems like the sympathetic nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, gastrointestinal system, and motor response system are activated. When a stress response occurs, these systems are either heightened or suppressed to help cope, thanks to the chemicals epinephrine and cortisol.

What is a threat? Threats can take a variety of forms; accidents, falls, diseases, surgeries, emotional trauma, etc. Tissues are influenced by how the individual thinks and feels, in addition to social and environmental factors. The authors propose that when individuals live with chronic pain, their body reacts as though they are under a constant threat. With this constant threat the system reacts and continues to react, and the nervous system is not allowed to return to baseline levels. This can create a patient presentation with immunodeficiency, GI sensitivity, poor motor control, and more. This sounds like most patients who walk into my clinic. The authors suggest that one system may be affected more and that can influence what the patient is diagnosed with even though the underlying biology is the same for many conditions. There are theories for why that happens; genetics, biological memory, or it could be the lens of the provider that the patient sees. There is a table in the article that shows symptoms, diagnosis, and current best evidence treatment for the conditions of fybromyalgia, chronic fatique syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease which is worth a look. The treatments all work to calm the central nervous system.

The authors go on to question the relationship between thyroid function and these conditions as changes in cortisol and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is fascinating, and confusing. Luckily, the Pelvic Floor Series Capstone course does a great job breaking it down.

Now that this hypothetical patient is in our treatment room what do we do? The authors suggest seeing these conditions for what they are: chronic pain conditions. They recommend that physical therapists see past the label that a patient may have picked up with a previous diagnosis, and keep the following in mind when treating these patients:

- They are hurting

- They are tired

- They may have lost hope

- They may be disillusioned by the medical community

- They need help

These people need the following from their medical providers:

- Compassion

- Dignity

- Respect

With empathy and understanding therapists can use skills in education, exercise and movement with the intent to improve system function (immune, neural, and endocrine), rather than fixing isolated mechanical deficits.

Louw, Adriaan PT, PhD; Schmidt, Stephen PT ; Zimney, Kory PT, DPT ; Puentedura, Emilio J. PT, DPT, PhD Treat the Patient, Not the Label: A Pain Neuroscience Update.[Editorial] Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 43(2):89-97, April/June 2019.

Part 2: The Drama Triangle

This is part two of a three-part series on self-care and preventing practitioner burnout from faculty member Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC. Part One is available here. Jennafer is the co-author and co-instructor of the along with Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC.

Augh, I was so frustrated with myself. I fell for it again. Here’s the scenario: a patient came in suffering excruciating pain. She had been to see a pelvic health professional as well as various medical professionals and was unable to get relief and answers for her rectal pain. She was desperate and called me “her last hope.” Phrases used included, “I need you! Fix me! I hear you are a miracle worker! If you can’t help me no one can!” And just like that I took on the role of Rescuer.

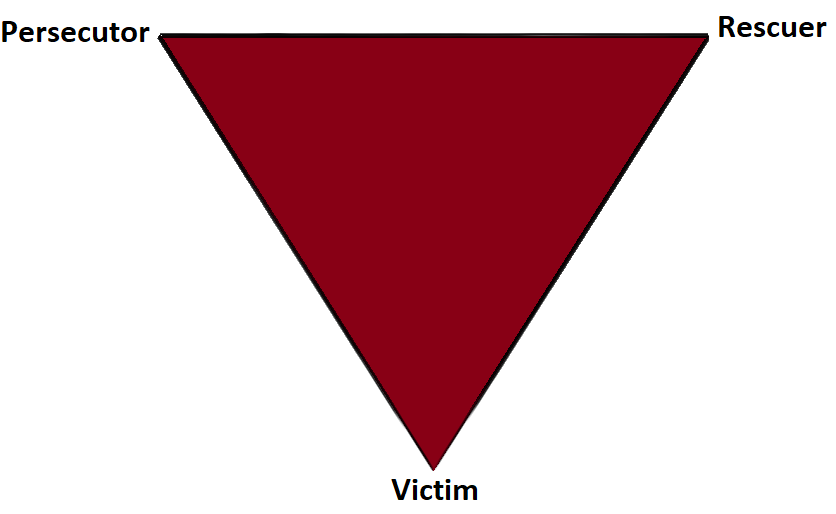

In 1968 a psychiatrist named Stephen Karpman developed a model of personal interaction that he called the Conflict Triangle. It has also become known as the Karpman Triangle, The Drama triangle or the Victim triangle. Per Wikipedia:

The Victim: The Victim's stance is "Poor me!" The Victim feels oppressed, helpless, hopeless, powerless and ashamed. They seem unable to make decisions, solve problems, take pleasure in life or achieve insight. The Victim, if not being persecuted, will seek out a Persecutor and also a Rescuer who may save the day, but may also perpetuate the Victim's negative feelings.

The Rescuer: The Rescuer's line is "Let me help you." A classic enabler, the Rescuer feels guilty if they don't rush to the rescue. Yet their rescuing has negative effects: It keeps the Victim dependent and gives the Victim permission to fail. The rewards derived from this rescue role are that the focus is taken off of the Rescuer. When they focus their energy on someone else, it enables them to ignore their own anxiety and issues. This rescue role is also pivotal because their actual primary interest is really an avoidance of their own problems disguised as concern for the victim’s needs.

The Persecutor: (a.k.a. Villain) The Persecutor insists, "It's your fault." The Persecutor is controlling, blaming, critical, oppressive, angry, authoritative, rigid, and superior.

What is interesting about this triangle is that the roles are constantly shifting. In full rescuer mode, I gladly took on this patient, intent on solving her problems. Over time, I saw that my consistent coaching for lifestyle change and self-care was falling on deaf ears. My patient was not following through with anything I asked of her; therefore my treatment plan was not working. The patient began to get frustrated with me. I then cast myself as the victim. She became my persecutor! While perhaps in her mind, I had failed as the rescuer, she was still the victim and I had become her persecutor. At the time, I did not have the skills to know how to navigate this situation in a positive or helpful way. Finally I sought the advice of my supervisor and my therapist to draw up a contract with this patient. The contract outlined each of our responsibilities. If either of us didn’t fulfill our responsibilities, the consequence would be ending our professional relationship. When she persisted, unwilling to do her part, I discharged her per our agreement.

What is interesting about this triangle is that the roles are constantly shifting. In full rescuer mode, I gladly took on this patient, intent on solving her problems. Over time, I saw that my consistent coaching for lifestyle change and self-care was falling on deaf ears. My patient was not following through with anything I asked of her; therefore my treatment plan was not working. The patient began to get frustrated with me. I then cast myself as the victim. She became my persecutor! While perhaps in her mind, I had failed as the rescuer, she was still the victim and I had become her persecutor. At the time, I did not have the skills to know how to navigate this situation in a positive or helpful way. Finally I sought the advice of my supervisor and my therapist to draw up a contract with this patient. The contract outlined each of our responsibilities. If either of us didn’t fulfill our responsibilities, the consequence would be ending our professional relationship. When she persisted, unwilling to do her part, I discharged her per our agreement.

I learned so much from this experience. Here are some things that I have implemented and may be helpful in your practice if you have similar challenges.

- In an initial visit with a new patient I explain that the patient and I make a team and we each have a role to play in reaching the patient’s goals.

- If someone says, “Fix me!” I say, “Think of me as your coach, I can show you how to help your body heal, but it’s your job to do the work.”

- When I hear, “Everyone says you are a miracle worker.” I say, “That is so kind, but it doesn’t work that way. Healing is complicated and everyone has their own journey.”

- In this way, with baby steps, we can get OUT of the drama triangle and into healthy relationships with our patients and the people in our lives.

- Consider the Winner's Triangle published by Acey Choy in 1990.

In her blog NextMeCoaching, Jessica Vader coaches on turning Drama and Control into a Winning situation.

The three roles in the Winner’s Triangle.

Vulnerable – a victim should be encouraged to accept their vulnerability, problem solve, and be more self-aware.

Assertive – a persecutor should be encouraged to ask for what they want, be assertive, but not punishing.

Caring – a rescuer should be encouraged to show concern and be caring, but not over reach and problem solve for others.

If you struggle with professional and personal boundaries, you are not alone, and you can get support. Consider talking with your supervisor, a counselor, reading a good book on the subject, and or taking Boundaries, Mediation and Self Care, a course offering through Herman and Wallace that was designed to help pelvic health professionals stay healthy and inspired while equipping therapists with new tools to share with their patients.

We hope you will join us for Boundaries, Mediation and Self Care this November 9-11, 2019 in San Diego, CA.

Look forward to my next blog where saying no takes an unexpected turn.

We are thrilled to announce that Herman and Wallace instructor, Carolyn McManus, MPT, will co-present an educational session with internationally recognized pain researcher Etienne Vachon-Pressseau, PhD at APTA’s NEXT meeting in Chicago on June 13. Dr. Vachon-Presseau is an assistant professor at the Alan Edwards Centre for Research on Pain at McGill University and has led pioneering research into stress-associated brain changes in patients with persistent pain.

In a presentation entitled, When Stress Complicates Care for Your Patient in Pain: Evidence-Based Mechanisms and Treatment, Dr. Vachon-Presseau will discuss the latest research and theory illuminating the role of stress in the maladaptive neuroplastic brain changes observed in patients with chronic pain. Carolyn will discuss direct clinical applications of this marterial and highlight research on the role of mindfulness in the self-regulation of stress and pain. She will share a practical model for integrating mindfulness into physical therapy for the treatment of persistent pain conditions.

In a presentation entitled, When Stress Complicates Care for Your Patient in Pain: Evidence-Based Mechanisms and Treatment, Dr. Vachon-Presseau will discuss the latest research and theory illuminating the role of stress in the maladaptive neuroplastic brain changes observed in patients with chronic pain. Carolyn will discuss direct clinical applications of this marterial and highlight research on the role of mindfulness in the self-regulation of stress and pain. She will share a practical model for integrating mindfulness into physical therapy for the treatment of persistent pain conditions.

We are excited that Carolyn has been offered this honor to co-present at NEXT with a world renown researcher in the field of pain and contribute her insights from an over 30-year career specializing in mindfulness and pain. She will offer her popular course, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, in Portland OR, July 27 and 28 and in Houston TX, October 26 and 27. We recommend these unique opportunities to train with Carolyn, a nationally recognized leader trailblazing the successful applications of mindfulness into the field of physical therapy. Hope to see you there!

The number of individuals who identify as transgender is growing each year. The Williams Institute estimated in 2016 that 0.6% of the U.S. population or roughly 1.4 million people identified as transgender (Flores, 2016). This was a 50% increase from a 2011 survey which estimated only 0.3% or 700,000 people identified as transgender (Gates, 2011). Though these numbers are growing each year, due to increased visibility and social acceptance, it is presumed that these numbers are underreported due to inadequate survey methods, stigma/fear associated with “coming out” and deficient definitions of the multitude of options for gender identity (Flores, 2016).

Though organizations such as WPATH have attempted to standardized care, the patient experience and reception of quality care are significantly lacking. In 2015 the National Center for Transgender Equality performed a groundbreaking survey of 27,215 respondents with the aim to “understand the lives and experiences of transgender people in the United States and the disparities that many transgender people face” (“About,”n.d., para. 1). This survey revealed that 33% of individuals who saw a health care provider had at least one negative experience related to being transgender (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Negative experiences included; being refused treatment, verbal harassment, physically or sexually assault, and teaching the provider about transgender people in order to get appropriate care (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Alternatively, 23% of respondents did not see a doctor when they needed to because of fear of being mistreated as a transgender person (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Though these statistics are staggering and affronting there is hope for a better future.

Research for the care of these patients, specifically related to pelvic floor physical therapy, is on the rise. In the Annals of Plastic Surgery, an article was published with the purpose to capture incidence and severity of pelvic floor dysfunction pre-surgery, monitor any progression of symptoms with standardized outcome measures and highlight the role of physical therapy in the treatment of patients undergoing vaginoplasty (Manrique, et al., 2019). While in the Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology a retrospective case series similarly focused on physical therapy pre and post-operatively highlighting dilator selection and success, pelvic floor dysfunction including bowel and bladder as well as reported abuse history (Jiang, Gallagher, Burchill, Berli, & Dugi, 2019). Through articles such as these clinicians can expect an uptick in calls questioning if they treat these patients. This begs the question of, "How can you best prepare?"

The answer is simple, attend continuing education. It is where you can not only learn evidence-based evaluation and treatment but also connect with other providers and mentors that care for these patients. In 2020 Herman & Wallace will be offering a continuing education course that serves this exact purpose. Keep your eyes on next years offerings, as spaces will surely fill quickly.

About. (n.d.). Retrieved May 15, 2019, from http://www.ustranssurvey.org/about

Dora Richter. (2019, May 09). Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dora_Richter

Jiang, D. D., Gallagher, S., Burchill, L., Berli, J., & Dugi, D. (2019). Implementation of a Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy Program for Transgender Women Undergoing Gender-Affirming Vaginoplasty. Obstetrics & Gynecology,133(5), 1003-1011. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000003236

Manrique, O. J., Adabi, K., Huang, T. C., Jorge-Martinez, J., Meihofer, L. E., Brassard, P., & Galan, R. (2019). Assessment of Pelvic Floor Anatomy for Male-to-Female Vaginoplasty and the Role of Physical Therapy on Functional and Patient-Reported Outcomes. Annals of Plastic Surgery,82(6), 661-666. doi:10.1097/sap.0000000000001680

National Center for Transgender Equality. (2015). Annual report of the U.S. Transgender Survey. Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Executive-Summary-Dec17.pdf

Wpath. (n.d.). Standards of Care version 7. Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc

Leg length discrepancy (LLD) is when there is a noticeable difference in length of one leg to the other. LLD is common and can be found in 70% of the population (Gurney, 2002). LLD can be structural or functional. Structural LLD is when a long bone in the leg is longer or shorter than the other. Structural LLD is often the result of congenital or boney damage of epiphyseal plate. Functional is when there is an apparent LLD from higher in the chain such as scoliosis. Generally as pelvic floor therapists we are orthopedic based therapists. In physical therapy school we learned that a leg length discrepancy had to be >1 cm to be considered significant, and based off of recent research that is still the case. Research in the last few years has focused on whether LLD has an effect on age related changes with osteoarthritis, posture & gait, and pain. Physiopedia suggests differential diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction, scoliosis, low back pain, iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome, stress fractures, and pronation. It can often feel like a chicken or egg question.

In the clinic I typically screen for a leg length discrepancy during my initial evaluation. A LLD may be noticed upon observation of gait assessment, standing posture, or part of the pelvic obliquity screen in standing and then in supine.

In the clinic I typically screen for a leg length discrepancy during my initial evaluation. A LLD may be noticed upon observation of gait assessment, standing posture, or part of the pelvic obliquity screen in standing and then in supine.

During gait, a LLD will create bilaterteral gait impairments. Khamis et al did a systematic review of LLD and gait deviations in 2017. They narrowed the search down to 12 articles and found that LLD >1cm was significantly related to gait deviations. These deviations occurred bilaterally, and while initially compensations occurred in the sagittal plane, as the LLD increased so did the gait deviations, and then affected frontal planes of motion as well. Resende et al (2016) agrees that even mild LLD should not be overlooked. They found that the most likely gait deviations were also in the sagittal planes and consisted of rearfoot and ankle dorsiflexion and inversion, knee flexion and adduction, hip adduction and flexion, and pelvic trendelenburg.

The sagittal, or right/left plane, and frontal, or front/back, plane involvement is consistent with the differential diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction, low back pain, and pronation. Really, one could justify why a LLD could contribute to pain and dysfunction in most of the lower body. It is reasonable to think that these compensational moments in gait over a long period create boney changes in the lower extremities which may contribute to low back pain.

Clinically, a leg length discrepancy can be assessed directly with a tape measure or indirectly with a shoe lift. Badii (2014) found a higher interrater reliability with the indirect method of a shoe lift as opposed to measuring with a tape measure.

Rannisto et al (2019) looked at leg length discrepancy among meat cutters with low back pain. All participants had been working for 10 years and were greater than 35 years old. Participants needed to have a LLD of 5mm (5mm is 0.5 cm) or more and complain of low back pain of >2/10 on visual analog scale (VAS). They were all given insoles and randomized into 2 groups; the intervention group were given lifts to correct the LLD about 70%; for example a 10mm LLD was corrected to 3 mm. The LLD was measured with a laser ultrasound technique. Participants were followed for 12 months. The intervention group had improvement in low back pain intensity, sciatica intensity, and took less sick time. Possibly the most amazing part is that for those that wore the heel lift at work the compliance was good.

Leg length discrepancy can often be an underlying component contributing to complaints of pain and dysfunction. It may have more of an effect on the populations who stand or walk for most of their work, and I wonder as more people transition to standing desks if we will see more people come into the clinic with a previously undiagnosed LLD.

My biggest clinical pearls from this research is that:

- Heel lifts can be used to diagnose and then for treatment (yay! One less step of getting the tape measure out)

- The heel lift does not have to be perfect. Clinically, I will try a lift and have the person walk, and then we can make a team decision if this lift is enough and feels better

- The gait compensations are consistently adduction and internal rotation throughout the lower body chain. I will continue to work on the opposing muscle groups; lateral rotators, hip extensors and abductors.

Leg Length Discrepancy can be evaluated using various assessments. To learn orthopedic evaluative techniques for patients, consider joining Lila Abbate in her course Advanced Orthopedic Assessment for the Pelvic Health Therapist.

Maziar Badii, A Nicole Wade, David R Collins, Savvakis Nicolaou, B Jacek Kobza, Jacek A Kopec, Comparison of lifts versus tape measure in determining leg length discrepancy; Journal of Rheumatology 2014, 41 (8): 1689-94

Renan A. Resende, Renata N. Kirkwood, Kevin J. Deluzio, Silvia Cabral, Sérgio T. Fonseca. "Biomechanical strategies implemented to compensate for mild leg length discrepancy during gait" Gait & Posture, Volume 46, 2016; 147-153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.03.012

Sam Khamis, Eli Carmeli, Relationship and significance of gait deviations associated with limb length discrepancy: A systematic review, Gait & Posture, Volume 57, 2017, 115-123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.05.028

Burke Gurney, Leg length discrepancy, Gait & Posture, Volume 15, Issue 2, 2002, Pages 195-206, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00148-5.

Satu Rannisto, Annaleena Okuloff, Jukka Uitti, et al. Correction of leg-length discrepancy among meat cutters with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2019;(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2478-3.

Everyday we as pelvic rehab providers get to help patients achieve their goals by meeting them where they are and guiding them along.

A couple of months ago I had a new patient come in to see me who was seven months status post c-section delivery of her first child. She was referred to physical therapy because she could not tolerate anything touching her lower abdomen and she was also unsure of how to start exercising again including returning to her yoga practice. I remember reading her referral and thinking that this should be a simple evaluation and treatment session. What actually happened was a little different.

Her delivery hadn’t gone the way she planned, and she was not comfortable discussing it at our first session. This patient had not looked at or touched her c-section incision besides drying it off after her shower for the seven months since delivery. Her physician had made a referral to PT and to a counselor within three months of delivery to help support the patients’ recovery. The patient had not followed through with the PT referral until she had significant encouragement from her counselor and physician.

Initially the patient declined any observation or palpation of her abdomen so at our first session we focused on thoracic range of motion, general posture, and encouraged her to start touching her abdomen through her clothes, even if avoiding direct touch to the incisional region. The patient was agreeable with this starting point. At the second session the patient was willing to have me look at her abdomen and touch the abdomen but she declined direct palpation of the scar region. With simple observation I could see a scar that was closed and healing but also that was pulled inferior towards her pubic bone. She was not comfortable laying flat on the treatment table and had to be supported in a semi-recline throughout the session. She also described buzzing symptoms at the scar region when she reached her arms overhead.

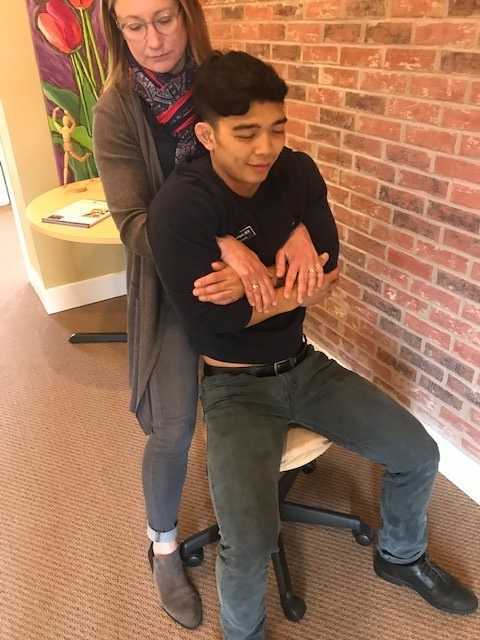

We started some gentle desensitization techniques as would be used with a person that had Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) after an injury. I focused those treatments to the abdominal region but avoided the scar region. We focused her home program on breathing into her abdomen allowing some stretch and expansion of the abdominal region. Her home program also included laying flat for five minutes per day. I asked her to notice any general tension throughout her body during the day and attempt to change it and release it if able.

By the fourth session we where able to begin direct palpation and manual therapy techniques to the c-section scar and the whole abdominal region. The patient was apprehensive but agreed to proceeding with utilizing techniques as described by Wasserman et al2018 including superficial skin rolling, direct scar mobilization and general petrissage/effleurage of the abdomen and lumbothoracic region.

Over the next five sessions the patient was able to start wearing undergarments and pants that touched her lower abdomen. She was able to perform her own self massage to the region and began an exercise program including prone press ups, progressive generalized trunk strengthening, and return to her prior-to-pregnancy yoga practice.

Drawing on the techniques we learn from multiple sources, applying them to the lumbopelvic region, and helping our patients wherever the client is in their journey to wellness, is what inspires me to keep learning.

Techniques like this are taught in my 2-day Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist course. I specifically wrote this course so that pelvic rehab therapists that are looking for more techniques and/or more confidence in their palpation skills would have a weekend to hone those skills. We spend time learning anatomy, learning palpation skills, manual techniques, problem solving home programs and discussing cases. Check out Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist - Raleigh, NC - June 22-23, 2019 for more information and I hope to see you there.

Wasserman, J. B., Abraham, K., Massery, M., Chu, J., Farrow, A., & Marcoux, B. C. (2018). Soft Tissue Mobilization Techniques Are Effective in Treating Chronic Pain Following Cesarean Section: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 42(3), 111-119.

In the United States, estimated direct medical costs for outpatient visits for chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is more than $2.8 billion per year.1 In a 2017 study in the Clinical Journal of Pain by Sanses et al, a detailed musculoskeletal exam of clients with CPP can assist both physicians as well as physical therapists in differential diagnosis and appropriate referrals for this population.

Evaluating a client with pelvic pain requires a skill set that includes direct pelvic floor as well as musculoskeletal test item clusters. The prioritization of which depends upon many factors including clinician discipline, experience, specialty vs. general setting, as well as client history, presentation and goals. In addition to the direct pelvic floor assessment, there are additional key musculoskeletal screening tests that are an essential part of a pelvic pain assessment. New this year, my course Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain will incorporate the use of Real Time Ultrasound in neuromuscular assessment and re-education of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall during the Sunday morning lab session.

Peery et al (2012) noted that abdominal pain was one of the most common presenting reasons for an outpatient physician visit in the United States. Abdominal pain is one of the many complaints that our clients may report requiring differential diagnosis including urogynecologic, colorectal, musculoskeletal, visceral or neurogenic causes. Lower abdominal quadrant pain may denote serious emergent pathology. Clinical findings, physical exam and client symptoms in addition to smart differential diagnosis must be used to determine if the abdominal pain is musculoskeletal in nature. Direct access requires physical therapists to perform a skilled initial screening for abdominal pain in order to determine if it is abdominal wall versus a visceral origin. Physicians are fluent in ruling out emergent pathology but may not be familiar with musculoskeletal tests for non-emergent pathology. Assessment of bowel and bladder function and habits are essential to perform. This blog specifically addresses three physical exam tests that can be performed as part of abdominal wall pain screening. According to Cartwright et al, the location of the abdominal pain should drive the evaluation.

Carnett’s test is a simple clinical test that assesses abdominal pain response when a client tenses their abdominal muscles. A positive Carnett’s sign denotes the origin of symptoms within the abdominal wall with a negative tests suggesting intra-abdominal pathology. The test is performed in supine, the clinician gently palpating the area of abdominal pain and has the client lift their head and shoulders off the table. Conditions such as myofascial trigger points, scar and muscular pain would be flared with palpation of the contractile tissue with activation of the abdominal wall muscles. If the pain is due to visceral origin, appendicitis for example, the pain would remain unchanged with palpation with head lift. Although some perform Carnett’s test by lifting both legs off the table, this method may cause unnecessary pain in clients with poor lumbopelvic control. (Figure 1) The head and shoulder lift option is felt to be comparable method of performing Carnett’s test.

Blumberg’s sign is most commonly used to rule in appendicitis, peritonitis or a visceral driver of right lower quadrant pain. The test is performed by the clinician applying deep pressure over McBurney’s point (Figure 2) with an abrupt and rapid release of pressure. Although there are anatomical variations in appendix location, pain reproduction is consistent with a positive test and immediate referral to the ER is indicated.

Thoracic dysfunction, including disc herniation, can result in abdominal pain.2 In thoracic discogenic driven abdominal pain, symptoms would likely be exacerbated by coughing, sneezing, spinal flexion and activities that would increase spinal loading. A simple screening for this is seated thoracic traction. If the client reports reduction or resolution of symptoms with traction, further musculoskeletal tests including regional movement and PIVM testing could be implemented to rule in or rule out need for diagnostic imaging.

In the Herman Wallace course “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain” participants learn a comprehensive musculoskeletal screen including abdominal, neural mobility and conductivity, pelvic ring, pelvic floor and biomechanical contributing factors to pelvic pain. Evidence based test item clusters are defined, along with their diagnostic accuracy, for all associated systems in order to outline a comprehensive screen for pelvic pain clients. To learn more about musculoskeletal screening for pelvic pain, check out faculty member Elizabeth Hampton PT, DPT, WCS, PRPC, BCB-PMD’s course Finding the Driver of Pelvic Pain, which is next offered Jun 28, 2019 - Jun 30, 2019 in Columbus, Ohio. We are fortunate to have Dick Poore, President of The Prometheus Group present on Sunday June 30th for technical support for the Real Time Ultrasound portion of the course.

1. Sanses et al. "The Pelvis and Beyond: Musculoskeletal Tender Points in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain". Clin. J. Pain. 2016 Aug. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000307

2. Papadakos et al. "Thoracic Disc Prolapse Presenting with Abdominal Pain: Case Report and Review of the Literature". Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 20019 Jul. doi: 10.1308/147870809X401038

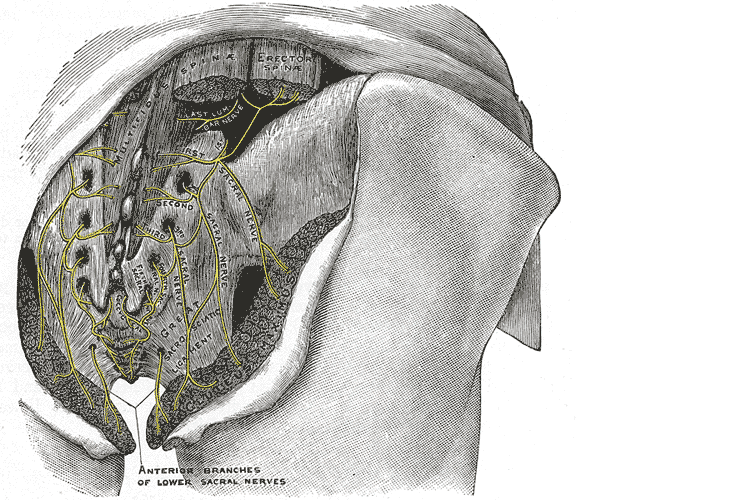

“My butt hurts.” This is such a common subjective complaint in my practice as a manual therapist, and many patients insist it must be a muscle problem or jump to the conclusion it must be “sciatica.” I often tell patients if they did not get shot or bit directly in the buttocks, the pain is most likely referred from nerves that originate in the spine. Although blunt trauma to the buttocks can certainly be the culprit for pain in the gluteal region, a basic understanding of the neural contribution is essential for providing appropriate treatment and a sensible explanation for patients.

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

Iwananga et al., (2018) presents a very recent article regarding the innervation of the piriformis muscle, which has been suspected to be the superior gluteal nerve, by dissecting each side from ten cadavers. Often the piriformis muscle can be compromised through total hip replacements with a posterior approach, hip injuries, or chronic pain disorders. This particular study verifies there is no singular nerve that innervates the piriformis muscle, and the most common innervation sources are the superior gluteal nerve (70% of the time) and the ventral rami of S1 (85% of the time) and S2 (70% of the time). The inferior gluteal nerve and the L5 ventral ramus were each found to be part of the innervation only 5% of the time.

Wang et al., (2018) focused on what causes gluteal pain with lumbar disc herniation, particularly at L4-5, L5-S1. They emphasize the important factor that dorsal nerve roots have sensory fibers and ventral roots contain motor neurons, and spinal nerves are mixed nerves, since they have ventral and dorsal roots. They discuss other contributing nerves, but continuing our focus on the superior gluteal nerve, it stems from L4-S1 ventral rami and not only allows movement of gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and gluteus maximus, it also provides sensation to the area. This nerve can certainly produce pain in the gluteal region when irritated. In lumbar disc herniation of L4-5 or L5-S1, the ventral rami of L5 or S1 can be comprised or irritated at the level of the nerve root and provoke gluteal pain because they mediate sensation in that area.

Once the superior gluteal nerve (or any sacral nerve) is implicated as the root of pain, should we just shrug our shoulders and send them to pain management? I strongly suggest we learn how to address the issue in therapy using our hands with manual techniques and appropriate exercises. The Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment course should be a priority on your bucket list of continuing education to help alleviate any further pain in the butt.

Lung K, Lui F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Superior Gluteal Nerve. [Updated 2018 Dec 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535408/

Iwanaga J, Eid S, Simonds E, Schumacher M, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. (2018). The Majority of Piriformis Muscles are Innervated by the Superior Gluteal Nerve. Clinical Anatomy. doi: 10.1002/ca.23311. [Epub ahead of print]

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Yan, Y., Zhang, L., Guo, C., Peng, Z., & Kong, Q. (2018). Possible pathogenic mechanism of gluteal pain in lumbar disc hernia. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 19(1), 214. doi:10.1186/s12891-018-2147-y

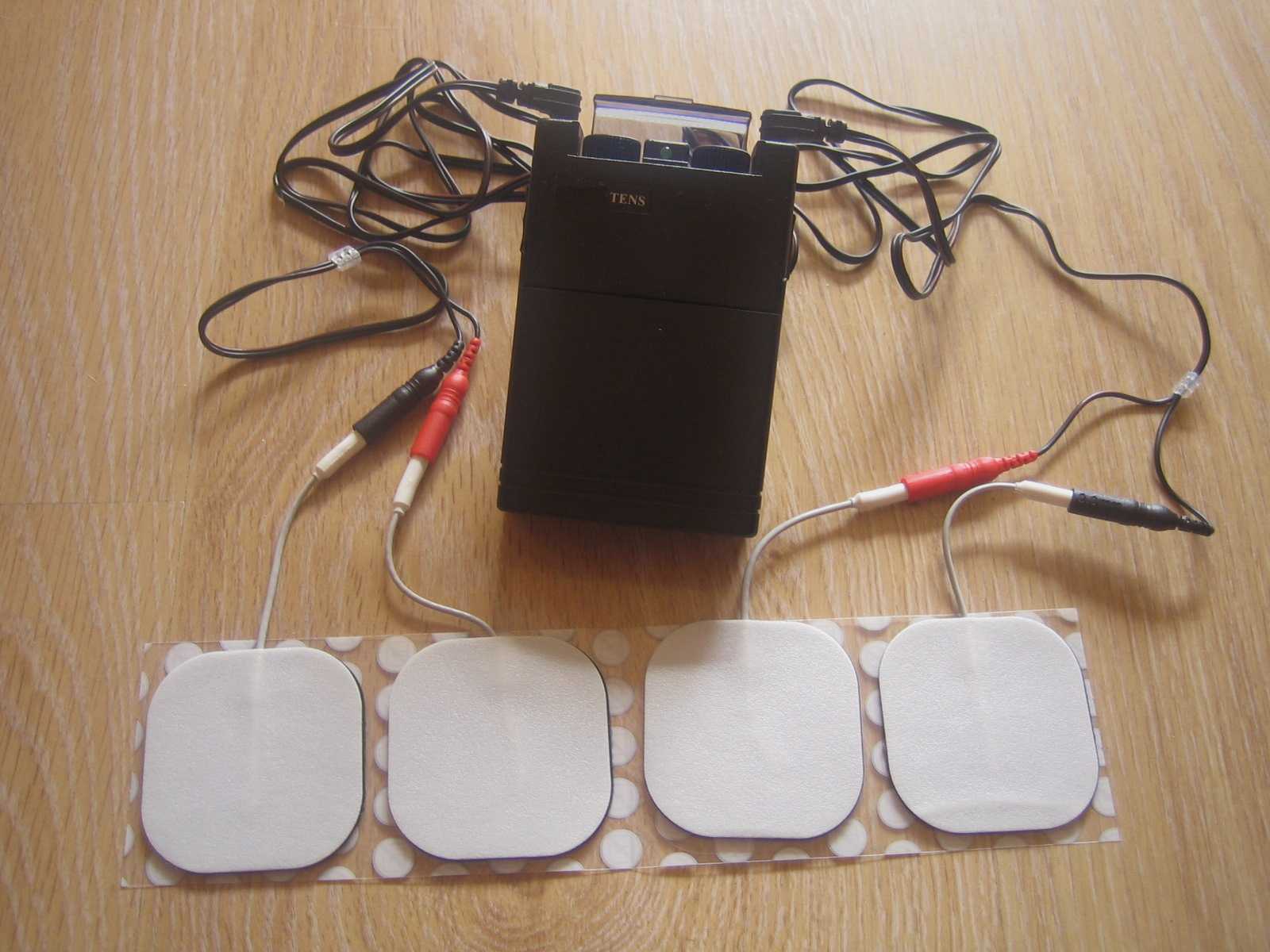

Tibial nerve stimulation has been shown in the literature to be effective for individuals experiencing idiopathic overactive bladder in randomized controlled trials. A systematic review was performed by Schneider, M.P. et al. in 2015 looking at safety and efficacy of its use in neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Many variables were examined in this review, which included 16 studies after exclusion. The review looked at:

- Acute stimulation (used during urodynamic assessment only)

- Chronic stimulation (6-12 weeks of daily-weekly use)

- Percutaneous or transcutaneous (frequencies, pulse widths, perception thresholds, durations)

- Urodynamic parameter changes baseline to post treatment

- Post void residual changes

- Bladder diary variables

- Patient adherence to tibial nerve stimulation

- Any adverse events

The exact mechanism of these types of neuromodulation stimulation procedures remains unclear, however it does appear to play a role in neuroplastic reorganization of cortical networks via peripheral afferents. No specific literature is currently available for the mechanism on action related to neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Different applications of neuromodulation however have been studied in the neurogenic populations.

One of the randomized controlled trials they report on included 13 people with Parkinson disease. The researchers looked at a comparison between the use of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (n = 8) and sham transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (n=5). Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) or sham stimulation was delivered to the people with Parkinson disease 2x/week for 5 weeks, 30-minute sessions (10 total sessions). Unilateral electrode placement was utilized, first electrode applied below the left medial malleolus and second electrode 5 cm cephalad. Confirmation of placement was obtained with left great toe plantar flexion. It is important to note the use of the stimulation intensity is reduced to below the motor threshold during the active treatment to direct the stimulation via peripheral afferents.

Urodynamic testing was performed at baseline and post treatment and revealed statistically significant differences with greater volumes at strong desire and urgency in the TTNS group. Additionally, the TTNS group experienced a 50% reduction in nocturia whereas in the sham group nocturia frequency remained the same. A three-day bladder diary completed by each of the groups also revealed significant positive changes in frequency, urgency, urge urinary incontinence and hesitancy only in the TTNS group.

Conservative management of neurogenic bladder in populations such as Parkinson disease is very important. These individuals experience lower quality of life ratings related to lower urinary tract dysfunction, higher risk of falling with needs to rush to the bathroom, their caregivers experience a higher level stress and burden of care, and tolerance to anticholinergic medications is very poor with multiple unwanted side effects that compound and worsen other symptoms that might be present from the disease process.

Please join us for Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab to learn how you can help your patients using this modality as one option. Participate in a lab session to learn electrode placement and other parameters to achieve best clinical results for your patients.

1. Perissinotto, M. C., D'Ancona, C. A. L., Lucio, A., Campos, R. M., & Abreu, A. (2015). Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms and its impact on health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 42(1), 94-99.

2. Schneider, M. P., Gross, T., Bachmann, L. M., Blok, B. F., Castro-Diaz, D., Del Popolo, G., ... & Kessler, T. M. (2015). Tibial nerve stimulation for treating neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: a systematic review. European urology, 68(5), 859-867.

The following is the first in a series on self-care and preventing practitioner burnout from faculty member Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC. Jennafer is the co-author and co-instructor of the Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation course along with Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC.

Part 1: Boundaries

“I just want you to fix me.” How many times have we heard this statement from our patients? And how do we respond? In my former life as a “rescuer” this statement would be a personal challenge. I wanted to be the fixer, find the solution and identify the thing that no one else had seen yet. Then, if I am being completely honest, bask in the glory of being the “miracle worker” and “never giving up” on my patient.

If you recognize that this attitude was going to run me into some problems, kudos to you. If you are thinking, “well of course, isn’t that your job as a pelvic floor physical therapist?” Please read on.

If you recognize that this attitude was going to run me into some problems, kudos to you. If you are thinking, “well of course, isn’t that your job as a pelvic floor physical therapist?” Please read on.

On my very first job performance review, when it came time to discuss my problem areas my supervisor relayed I was “too nice” and cited some examples: giving a patient a ride home after therapy (it was raining and she would have had to wait for the bus), coming in on Saturdays to care for patients (he was sick and couldn’t make it in during the week but was making really good progress). You get the picture. At the time, I didn’t understand how this could be something I needed to work on. I was going above and beyond and I got so much satisfaction from taking care of others!

Fast forward 10 years and add to my life a husband, two daughters, a teaching job, part time homeschooling, and writing course material. I was an emotional mess. Anxiety was my permanent state of mind. I gave my best to my patients while my family got my meager emotional leftovers. Something had to change and luckily it did. I got help and learned exactly what boundaries are and how to develop as well as enforce them.

There are several resources that discuss professional boundaries in health care, like this from Nursing Made Incredibly Easy. In this particular article, health care professionals are exhorted to stay in the “zone of helpfulness” and avoid becoming under involved or over involved with patients. Health care professionals are also urged to examine their own motivation. Am I using my relationship with my patient to fulfill my own needs? Am I over involved so that I can justify my own worth?

Here are some warning signs that you are straying away from healthy boundaries with patients and becoming over involved:

- Discussing your intimate or personal issues with a patient

- Spending more time with a patient than scheduled or seeing a patient outside of work

- Taking a patient's side when there's a disagreement between the patient and his or her close relations

- Believing that you are the only health care member that can help or understand a patient

For some people, certain patients who push professional boundaries will cause the therapist to feel threatened and under activity is the result. This might result in talking badly about the patient to other staff, distancing ourselves, showing disinterest in their case, or failing to utilize best care practices for the patient.

Per Remshard 2012, “When you begin to feel a bit detached, stand back and evaluate your interactions. If you sense that boundaries are becoming blurred in any patient care situation, seek guidance from your supervisor. A sentinel question to ask is: ‘Will this intervention benefit the patient or does it satisfy some need in me?’”

Healthy professional boundaries are imperative for us and for our patients. Boundaries also help prevent burnout. Remshard delineates what healthy boundaries look like:

- Treat all patients, at all times, with dignity and respect.

- Inspire confidence in all patients by speaking, acting, and dressing professionally.

- Through your example, motivate those you work with to talk about and treat patients and their families respectfully.

- Be fair and consistent with each patient to inspire trust, amplify your professionalism, and enhance your credibility.

If you struggle with professional and personal boundaries, you are not alone and you can get support. Consider talking with your supervisor, a counselor, reading a good book on the subject or taking Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation, a course offering through Herman and Wallace that was designed to help pelvic health professionals stay healthy and inspired while equipping therapists with new tools to share with their patients.

We hope you will join us for Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation this November 9-11, 2019 in San Diego, CA.

Look forward to my next blog where The Rescuer (me) needs Rescuing and learn about the Drama Triangle.

Remshardt, Mary Ann EdD, MSN, RN "Do you know your professional boundaries?" Nursing Made Incredibly Easy!: January/February 2012 - Volume 10 - Issue 1 - p 5–6 doi: 10.1097/01.NME.0000406039.61410.a5

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com/