Coaching Patients to Engage in Positive Activities to Improve Outcomes

Substantial attention has been given to the impact of negative emotional states on persistent pain conditions. The adverse effects of anger, fear, anxiety and depression on pain are well-documented. Complementing this emphasis on negative emotions, Hanssen and colleagues suggest that interventions aimed at cultivating positive emotional states may have a role to play in pain reduction and/or improved well-being in patients, despite pain. They suggest positive affect may promote adaptive function and buffer the adversities of a chronic pain condition.

Hanssen and colleagues propose positive psychology interventions could contribute to improved pain, mood and behavioral measures through various mechanisms. These include the modulation of spinal and supraspinal nociceptive pathways, buffering the stress reaction and reducing stress-induced hyperalgesia, broadening attention, decreasing negative pain-related cognitions, diminishing rigid behavioral responses and promoting behavioral flexibility.

Hanssen and colleagues propose positive psychology interventions could contribute to improved pain, mood and behavioral measures through various mechanisms. These include the modulation of spinal and supraspinal nociceptive pathways, buffering the stress reaction and reducing stress-induced hyperalgesia, broadening attention, decreasing negative pain-related cognitions, diminishing rigid behavioral responses and promoting behavioral flexibility.

In a feasibility trial, 96 patients were randomized to a computer-based positive activity intervention or control condition. The intervention required participants perform at least one positive activity for at least 15 minutes at least 1 day/week for 8 weeks. The positive activity included such tasks as performing good deeds for others, counting blessings, taking delight in life’s momentary wonders and pleasures, writing about best possible future selves, exercising or devoting time to pursuing a meaningful goal. The control group was instructed to be attentive to their surroundings and write about events or activities for at least 15 minutes at least 1 day/week for 8 weeks. Those in the positive activity intervention demonstrated significant improvements in pain intensity, pain interference, pain control, life satisfaction, and depression, and at program completion and 2-month follow-up. Based on these promising results, authors suggest that a full trial of the intervention is warranted.

Rehabilitation professionals often encourage patients with persistent pain conditions to participate in activities they enjoy. This research highlights the importance of this instruction and patient guidelines can include the activities identified in the Muller article. In addition, mindful awareness training may further enhance a patient’s experience as he or she learns to pay close attention to the physical sensations, emotions and thoughts that accompany positive experiences. I look forward to discussing this article as well as sharing the principles and practices of mindfulness in my upcoming course, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment at Samuel Merritt University, Oakland, CA. Course participants will learn about mindfulness and pain research, practice mindful breathing, body scan and movement and expand their pain treatment tool box with practical strategies to improve pain treatment outcomes. I hope you will join me!

Hanssen MM, Peters ML, Boselie JJ, Meulders A. Can positive affect attenuate (persistent) pain? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(12):80.

Muller R, Gertz KJ, Molton IR, et al. Effects of a tailored positive psychology intervention on well-being and pain in individuals with chronic pain and physical disability: a feasibility trial. Clin J Pain.2016;32(1):32-44.

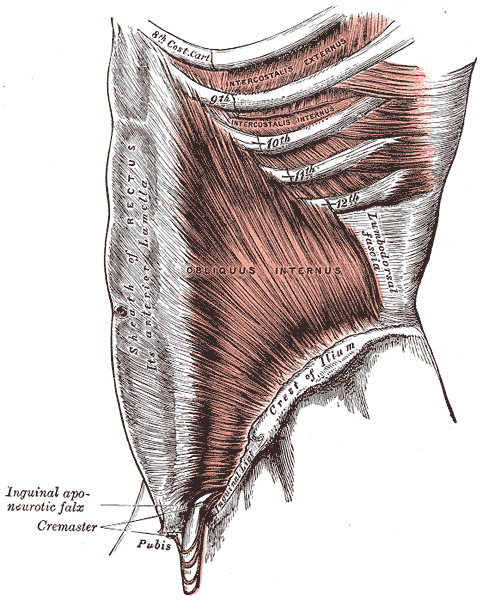

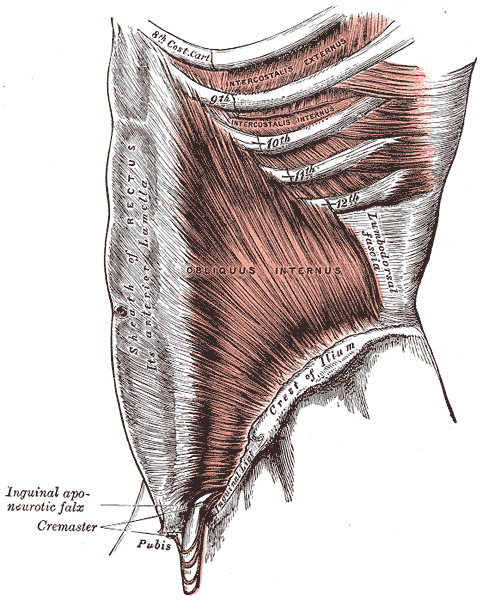

A couple of years ago, I wrote a blog about an interesting article by Hides and Stanton that related size and strength of the multifidus to the risk for lower extremity injury in Australian professional football players.

Now some of the same researchers are looking above. A prospective cohort study has recently been published that examined factors and their effects on concussions. Physical measurements of risk factors were taken in pre-season among Australian football players. These measurements included balance, vestibular function, and spinal control. To measure these outcomes the following tests were included: for balance the amount of sway across six test conditions were performed; vestibular function was tested with assessments of ocular-motor and vestibular ocular reflex; and for spinal control cervical joint position error, multifidus size, and contraction ability was tested. The objective measure was concussion injury obtained during the season diagnosed by the medical staff.

Now some of the same researchers are looking above. A prospective cohort study has recently been published that examined factors and their effects on concussions. Physical measurements of risk factors were taken in pre-season among Australian football players. These measurements included balance, vestibular function, and spinal control. To measure these outcomes the following tests were included: for balance the amount of sway across six test conditions were performed; vestibular function was tested with assessments of ocular-motor and vestibular ocular reflex; and for spinal control cervical joint position error, multifidus size, and contraction ability was tested. The objective measure was concussion injury obtained during the season diagnosed by the medical staff.

The findings were so interesting! Age, height, weight, and number of years playing football were not associated with concussion. Cross-sectional area of the multifidus at L5 was 10% smaller in players who went on to sustain a concussion compared to players that did not receive a concussion. There were no significant differences observed between the players that received concussion and those who did not with respect to the other physical measures that were obtained.

With all the recent evidence about the harmful effects of concussions amongst our athletes, I find this information amazing and am excited to see where the researchers take this in the future. The next question for the physical therapist is how do we train the multifidus? The multifidus can be difficult to retrain in some individuals. It is a hard muscle for some patients to learn to recruit. Biofeedback using ultrasound imaging can make this daunting task easier for many patients. With the cost of ultrasound units coming down, it is also a very reasonable tool for clinics to look at investing in.

Join me to learn more about the multifidus and how to use ultrasound imaging in the retraining process. Future course offerings include August in New Jersey, and November in San Diego. I look forward to seeing you there!

Hides, Stanton. Can motor control training lower the risk of injury for professional football players? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014; 46(4): 762-8.

Leung, Hides, Franettovich Smith, et al. Spinal control is related to concussion in professional footballers. Brit J of Sports Med. 2017; 51(11).

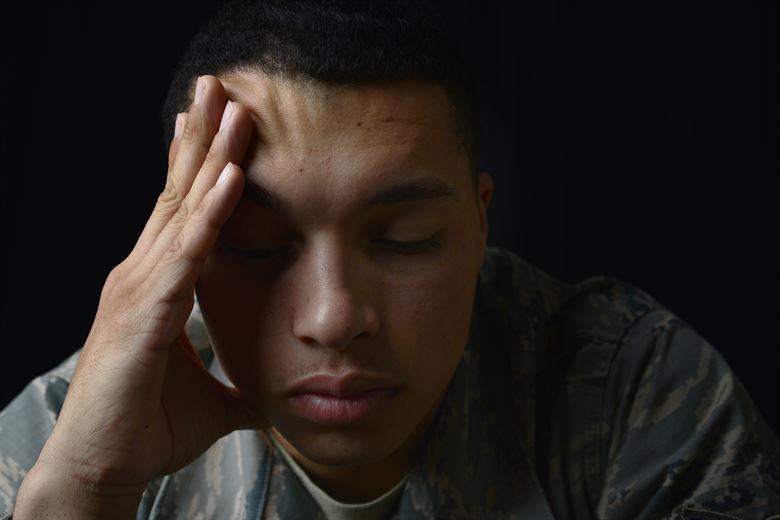

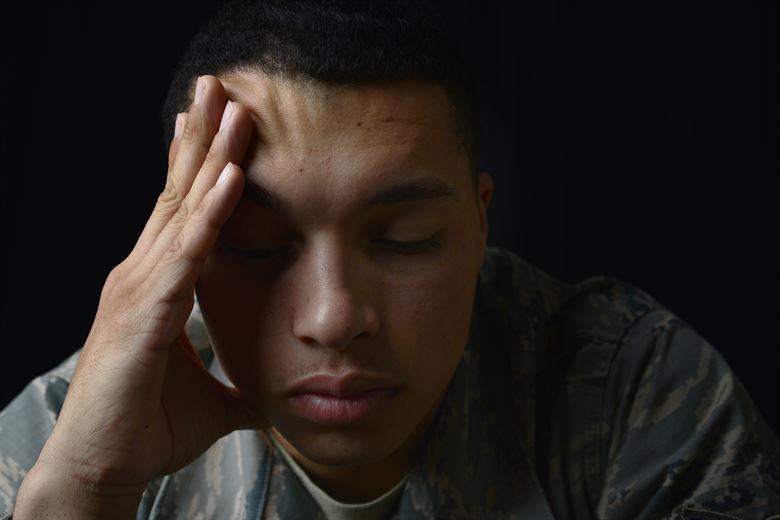

When I mentioned to a patient I was writing a blog on yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), she poured out her story to me. Her ex-husband had been abusive, first verbally and emotionally, and then came the day he shook her. Violently. She considered taking her own life in the dark days that followed. Yoga, particularly the meditation aspect, as well as other counseling, brought her to a better place over time. Decades later, she is happily married and has practiced yoga faithfully ever since. Sometimes a therapy’s anecdotal evidence is so powerful academic research is merely icing on the cake.

This study by Walker and Pacik (2017) included 3 voluntary participants: a 75 and a 72 year old male veteran and a 57 year old female veteran, all whom were experiencing a varying cluster of PTSD symptoms for longer than 6 months. Pre- and post-course scores were evaluated from the PTSD Checklist (a 20-item self-reported checklist), the Military Version (PCL-M). All the participants reported decreased symptoms of PTSD after the 5 day training course. The PCL-M scores were reduced in all 3 participants, particularly in the avoidance and increased arousal categories. Even the participant with the most severe symptoms showed impressive improvement. These authors concluded Sudarshan Kriya (SKY) seemed to decrease the symptoms of PTSD in 3 military veterans.

Cushing et al., (2018) recently published online a study testing the impact of yoga on post-9/11 veterans diagnosed with PTSD. The participants were >18 years old and scored at least 30 on the PTSD Checklist-Military version (PCL-M). They participated in weekly 60-minute yoga sessions for 6 weeks including Vinyasa-style yoga and a trauma-sensitive, military-culture based approach taught by a yoga instructor and post-9/11 veteran. Pre- and post-intervention scores were obtained by 18 veterans. Their PTSD symptoms decreased, and statistical and clinical improvements in the PCL-M scores were noted. They also had improved mindfulness scores and decreased insomnia, depression, and anxiety. The authors concluded a trauma-sensitive yoga intervention may be effective for veterans with PTSD symptoms.

Domestic violence, sexual assault, and unimaginable military experiences can all result in PTSD. People in our profession and even more likely, the patients we treat, may live with these horrors in the deepest recesses of their minds. Yoga is gaining acceptance as an adjunctive therapy to improving the symptoms of PTSD. The Trauma Awareness for the Physical Therapist course may assist in shedding light on a dark subject.

Walker, J., & Pacik, D. (2017). Controlled Rhythmic Yogic Breathing as Complementary Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Military Veterans: A Case Series. Medical Acupuncture, 29(4), 232–238.

Cushing, RE, Braun, KL, Alden C-Iayt, SW, Katz ,AR. (2018). Military-Tailored Yoga for Veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Military Medicine. doi:org/10.1093/milmed/usx071

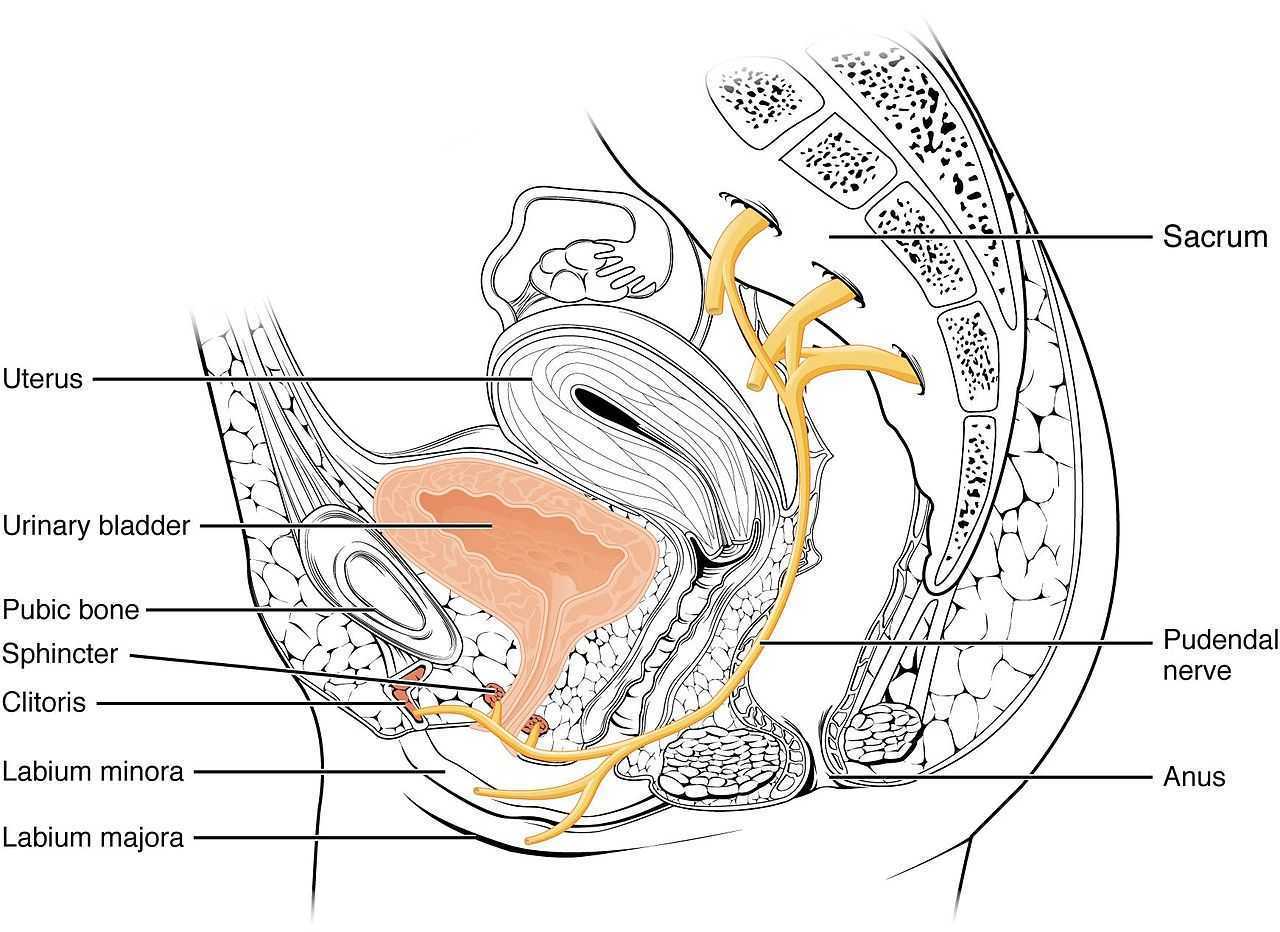

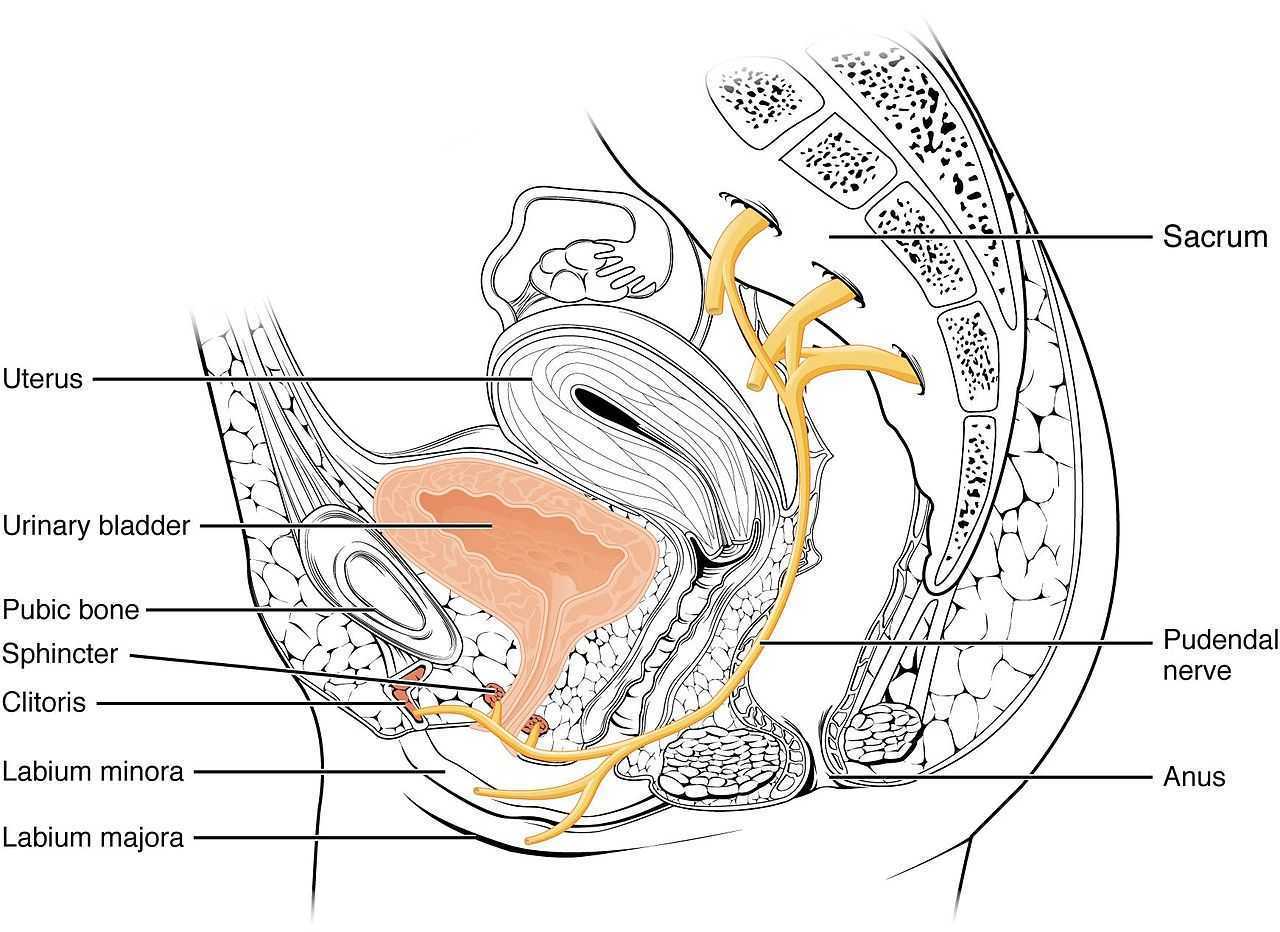

My 6 year old girl (going on 13) asks “Alexa” to play the Descendants II soundtrack over and over again. So the song, “Space Between,” was lingering in my head while reading the most recent articles on pudendal neuralgia, particularly when pudendal entrapment is to blame. After all, entrapment, by medical standards, describes a peripheral nerve basically being caught in between two surrounding anatomical structures.

Ploteau et al., (2016) presented 2 case studies highlighting the warning signs when pudendal nerve entrapment does not follow the Nantes criteria. A brief summary of those 5 criteria follows:

Ploteau et al., (2016) presented 2 case studies highlighting the warning signs when pudendal nerve entrapment does not follow the Nantes criteria. A brief summary of those 5 criteria follows:

- Pain in the region of the pudendal nerve innervation from anus to penis or clitoris.

- Pain most predominant while sitting.

- The patient does not wake at night from the pain.

- No sensory impairment can be objectively identified.

- Diagnostic pudendal nerve block relieves the pain.

The case studies of a 31 and a 68 year old female revealed endometrial stromal sarcoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma in the ischiorectal fossa, with night pain was noted in both patients, as well as no pain with sitting or defecation, respectively. Clinicians must always be mindful to resolve red flags in patients.

In 2016, Florian-Rodriguez, et al., studied cadavers to determine the nerves associated with the sacrospinous ligament, focusing on the inferior gluteal nerve. Fourteen cadavers were observed, noting the distance from various nerves to the sacrospinous ligament (from a pelvic approach) and to the ischial spine (from a gluteal approach). The S3 nerve was closest to the sacrospinous ligament, and the pudendal nerve was the closest to the ischial spine. In 85% of subjects, 1 to 3 branches from S3/S4 nerves pierced or ran anterior to the sacrotuberous ligament and pierced the inferior part of the gluteus maximus muscle. The authors concluded the inferior gluteal nerve was less likely to be the source of postoperative gluteal pain after sacrospinous ligament fixation; however, as the pudendal nerve branches from S2-4, it was more likely to be implicated in postoperative gluteal pain.

A study by Ploteau et al. (2017) explored the anatomical position of the pudendal nerve in people with pudendal neuralgia. In 100 patients who met the Nantes criteria, 145 pudendal nerves were surgically decompressed via a transgluteal approach. At least one segment of the pudendal nerve was compressed in 95 of the patients, either in the infrapiriform foramen, ischial spine, or Alcock’s canal. In 74% of patients, nerve entrapment was between the sacrospinous ligament and the sacrotuberous ligament. Anatomical variants were found in 13% of patients, often with a transligamentous course of the nerve.

When the pudendal nerve is caught in the narrow space between ligaments in the pelvis, diagnosing the source of pain is paramount. Research supports a gluteal approach in releasing the entrapped nerve. Post-surgical care falls into the hands of pelvic floor therapists, so taking “Pudendal Neuralgia and Nerve Entrapment: Evaluation and Treatment” may be something to consider in order to provide optimal care.

Ploteau, S, Cardaillac, C, Perrouin-Verbe, MA, Riant, T, Labat, JJ. (2016). Pudendal Neuralgia Due to Pudendal Nerve Entrapment: Warning Signs Observed in Two Cases and Review of the Literature. Pain Physician. 19(3):E449-54

Florian-Rodriguez, ME, Hare, A, Chin, K, Phelan, JN, Ripperda, CM, Corton, MM. (2016). Inferior gluteal and other nerves associated with sacrospinous ligament: a cadaver study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 215(5):646.e1-646.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.025

Ploteau, S, Perrouin-Verbe, MA, Labat, JJ, Riant, T, Levesque, A, Robert, R. (2017). Anatomical Variants of the Pudendal Nerve Observed during a Transgluteal Surgical Approach in a Population of Patients with Pudendal Neuralgia. Pain Physician. 20(1):E137-E143

Neurophysiology is a dynamic and highly complex system of neurological connections and interactions that allow for bodily performance. When all of those connections are working correctly, our bodies can function at optimal levels. When there is a break or injury to those connections, dysfunction results but amazingly in some circumstances, our bodies have work arounds to allow for certain functions to continue working.

If we take the sexual neural control system of the male, for instance, a perfect example of this can be described. Many men were injured fighting in World War II. During their time in battle, many experienced spinal cord injuries. Some of these injuries were severe resulting in complete spinal cord damage at level of injury. A physician, Herbert Talbot, in 1949, documented his examination of 200 men with paraplegia. Two thirds of the men were surprisingly able to achieve erections and some were able to experience vaginal penetration and orgasm. Much of their basic functionality had been lost however amazingly there was preservation of erectile function.

The reason these men with paraplegia were able to maintain erectile or orgasm functionality is due to the physiological function in the sacral spinal cord. A reflex arc is present in this region. The definition of a reflex arc is a nerve pathway that has a reflexive action involving sensory input from a peripheral somatic or autonomic nerve synapsing to a relay neuron or interneuron in the sacral cord segment then synapsing to a motor nerve for output to the muscular region. These messages do not need to travel up the spinal cord to the brain in order to be activated. Instead they work within a ‘loop’ at the sacral spinal cord level. In the case of spinal cord injury, erectile function as well as other functions controlled by reflex arcs, can be preserved.

For women, the same is true. In order for a female to have engorgement of the clitoris or orgasm, the sacral spinal reflex arc needs to be intact. If a woman experiences a spinal cord injury above the sacral region, the ability to have a reflexive orgasm within the sacral spinal reflex arc will remain.

The sacral reflex arc also plays an important role in activation of the pelvic floor muscles during the sexual response cycle. During genital stimulation in both the male and female, the bulbospongiosus or bulbocavernosus begins to activate in a reflexive pattern to hinder the outflow of blood from the region which facilitates erectile tissue of the penis and clitoris to become erect. This can then be followed by rhythmic reflexive contractions of the pelvic floor musculature during orgasm.

To learn more about the implications that neurologic disorders can have on the sexual system, please join us for Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab, coming to Grand Rapids, MI in September.

Goldstein, I. (2000). Male sexual circuitry. Scientific American, 283(2), 70-75.

Sipski, M. L. (2001). Sexual response in women with spinal cord injury: neurologic pathways and recommendations for the use of electrical stimulation. The journal of spinal cord medicine, 24(3), 155-158.

Wald, A. (2012). Neuromuscular Physiology of the Pelvic Floor. In Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract (Fifth Edition)(pp. 1023-1040).

In the dim and distant past, before I specialised in pelvic rehab, I worked in sports medicine and orthopaedics. Like all good therapists, I was taught to screen for cauda equina issues – I would ask a blanket question ‘Any problems with your bladder or bowel?’ whilst silently praying ‘Please say no so we don’t have to talk about it…’ Fast forward twenty years and now, of course, it is pretty much all I talk about!

But what about the crossover between sports medicine and pelvic health? The issues around continence and prolapse in athletes is finally starting to get the attention it deserves – we know female athletes, even elite nulliparous athletes, have pelvic floor dysfunction, particularly stress incontinence. We are also starting to recognise the issues postnatal athletes face in returning to their previous level of sporting participation. We have seen the changing terminology around the Female Athlete Triad, as it morphed to the Female Athlete Tetrad and eventually to RED S (Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome) and an overdue acknowledgement by the IOC that these issues affected male athletes too. All of these issues are extensively covered in my Athlete & The Pelvic Floor’ course, which is taking place twice in 2018.

But what about pelvic pain in athletes?

How can we ensure that pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is on the radar for a differential diagnosis, or perhaps a concomitant factor, when it comes to athletes presenting with hip, pelvis or groin pain? Gluteal injuries, proximal hamstring injuries, and pelvic floor disorders have been reported in the literature among runners: with some suggestions that hip, pelvis, and/or groin injuries occur in 3.3% to 11.5% of long distance runners.

How can we ensure that pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is on the radar for a differential diagnosis, or perhaps a concomitant factor, when it comes to athletes presenting with hip, pelvis or groin pain? Gluteal injuries, proximal hamstring injuries, and pelvic floor disorders have been reported in the literature among runners: with some suggestions that hip, pelvis, and/or groin injuries occur in 3.3% to 11.5% of long distance runners.

In Podschun’s 2013 paper ‘Differential diagnosis of deep gluteal pain in a female runner with pelvic involvement: a case report’, the author explored the case of a 45-year-old female distance runner who was referred to physical therapy for proximal hamstring pain that had been present for several months. This pain limited her ability to tolerate sitting and caused her to cease running. Examination of the patient's lumbar spine, pelvis, and lower extremity led to the initial differential diagnosis of hamstring syndrome and ischiogluteal bursitis. The patient's primary symptoms improved during the initial four visits, which focused on education, pain management, trunk stabilization and gluteus maximus strengthening, however pelvic pain persisted. Further examination led to a secondary diagnosis of pelvic floor hypertonic disorder. Interventions to address the pelvic floor led to resolution of symptoms and return to running.

‘This case suggests the interdependence of lumbopelvic and lower extremity kinematics in complaints of hamstring, posterior thigh and pelvic floor disorders. This case highlights the importance of a thorough examination as well as the need to consider a regional interdependence of the pelvic floor and lower quarter when treating individuals with proximal hamstring pain.’ (Podschun 2013)

Many athletes who present with proximal hamstring tendinopathy or recurrent hamstring strains, display poor ability to control their pelvic position throughout the performance of functional movements for their sport: along with a graded eccentric programme, Sherry & Best concluded ‘…A rehabilitation program consisting of progressive agility and trunk stabilization exercises is more effective than a program emphasizing isolated hamstring stretching and strengthening in promoting return to sports and preventing injury recurrence in athletes suffering an acute hamstring strain’

If you are interested in learning more about how pelvic floor dysfunction affects both male and female athletes, including broadening your differential diagnosis skills and expanding your external treatment strategy toolbox, then consider coming along to my course ‘The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor’ in Chicago this June or Columbus, OH in October.

The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), Mountjoy et al 2014: http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/48/7/491

‘DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DEEP GLUTEAL PAIN IN A FEMALE RUNNER WITH PELVIC INVOLVEMENT: A CASE REPORT’ Podschun A et al Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013 Aug; 8(4): 462–471. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3812833/

‘A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains’ Sherry MA, Best TM J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004 Mar;34(3):116-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15089024

Using sEMG biofeedback to get real-time results

Tiffany Lee, MA, OTR, BCB-PMD and Jane Kaufman, PT, BCB-PMD are internationally board-certified clinicians in the treatment of pelvic floor muscle dysfunction through the Biofeedback Certification International Alliance. Combined, they have over fifty years of treatment experience using sEMG biofeedback. Their new course, “Biofeedback for Pelvic Floor Muscle Dysfunction”, will provide the nuts and bolts of this powerful tool so that clinicians can return to the clinic after this course with another component to their toolbox of treatment strategies.

As a clinician treating patients with pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, have you gone away from a treatment session and asked yourself ‘what else can I do for this patient?’. Have you considered adding surface EMG, often referred to as biofeedback, to your treatment plan, but aren’t sure how to go about it correctly or effectively? Perhaps you think you can’t use the sensor because the patient has pain. Maybe you think biofeedback only helps with up-training or strengthening.

As a clinician treating patients with pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, have you gone away from a treatment session and asked yourself ‘what else can I do for this patient?’. Have you considered adding surface EMG, often referred to as biofeedback, to your treatment plan, but aren’t sure how to go about it correctly or effectively? Perhaps you think you can’t use the sensor because the patient has pain. Maybe you think biofeedback only helps with up-training or strengthening.

So exactly what is biofeedback? Why should I consider this modality? Biofeedback provides a non-invasive opportunity for patients to see muscle function visualized on a computer screen in a way that allows for immediate feedback, simple representation of muscle function, and allows the patient and the clinician the opportunity to alter the physiological process of the muscle through basic learning strategies and skilled cues. Many patients gain knowledge and awareness of the pelvic floor muscle through tactile feedback, but the visual representation is what helps patients really hone in on body awareness and connect all the dots. Here are a few comments that our patients have made; “I can now pay attention to my muscle while at work thanks to the visual of my muscle when sitting and standing”; “I needed to see my muscle to fully understand how to release the tension in it “; “I totally get what I need to do now that I have a clear picture of what you want”; “Seeing is believing”.

A 2017 study by Moretti, E., et al. is a great article that helps support the concept that measuring the pelvic floor electrical activity through a standard vaginal sensor is not always an option. For many patients, use of surface electrodes with peri-anal electrodes will provide the same reading and offer a more comfortable alternative for those patients who cannot use an internal sensor. This allows the clinician more opportunities to use this treatment modality with ease and assurance that the patient can learn from the visual representation of the muscle without fear of penetration from a sensor, and get great results!

In another study by Aysun Ozlu MD, et al. the authors conclude that biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle training, in addition to a home exercise program, improves stress urinary incontinence rates more than home exercise program alone.

Herman & Wallace is offering a course for clinicians in Alexandria, Virginia this June that will answer all of your questions and concerns about this fabulous treatment tool: biofeedback! This course enables the clinician to learn and practice this valuable tool and gain knowledge about the benefits of this modality, so that treatment can begin immediately with ample opportunity for patient’s positive feedback and awareness of muscle function. Participants will experience being a biofeedback practitioner and patient (using a self-inserted vaginal or rectal sensor). Participants will be administering biofeedback assessments, analyzing and interpreting sEMG signals, conducting treatment sessions, and role-playing patient instruction/education for each diagnosis presented during the many hands-on lab experiences. Biofeedback is a powerful tool that can benefit your patient population, and add to your skill-set.

Moretti, E., Galvao de moura Filho, A., Correia de Almedia, J., Araaujo, C., Lemos, C. “Electromyographic assessment of women’s pelvic floor: What is the best place for a superficial sensor?” Neurology and Urodynamics; 2017; 9999:1-7.;

Aysun Ozlu MD, Neemettin Yildiz MD, Ozer Oztekin MD, “Comparison of the efficacy of perineal and intravaginal biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle exercises in women with urodynamic stress urinary incontinence”

Advancing Understanding of Nutrition’s Role in…..Well….Everything

Gratitude filled my heart after being able to take part in the pre-conference course sponsored by the APTA Orthopedic Section’s Pain Management Special Interest Group this past February. For two days, participants heard from leaders in the field of progressive pain management with integrative topics including neuroscience, cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, sleep, yoga, and mindfulness to name a few. It’s exciting to witness and participate in the evolution of integrative thinking in physical therapy. When it was my turn to deliver the presentation, I had prepared about nutrition and pain, I could hardly contain my passion. While so much of our pain-related focus is placed on the brain, I realized acutely the stone yet unturned is the involvement of the enteric nervous system (aka the gut) on pain and….well…everything.

Much appreciation is due to those on the forefront of pain sciences for their research, their insight, their tireless work to fill our tool boxes with pain education concepts. Neuroscience has made tremendous leaps and bounds as has corresponding digital media to help explain pain to our patients. One such brilliant 5-minute tool can be found on the Live Active YouTube channel.

What I love about this video is how intelligently (and artistically!) it puts into accessible language some incredibly complex processes. It even mentions lifestyle and nutrition as playing a role in what is commonly referred to as a maladaptive central nervous system.

"Maladaptive central nervous system"

Ok. I’ll admit, I struggle with the implications of this term. However, what doesn’t sit right with me is the concept of chronic or persistent pain being entirely in the brain as though the brain is a static entity. We know the brain to be plastic but often do not identify just how this is so.

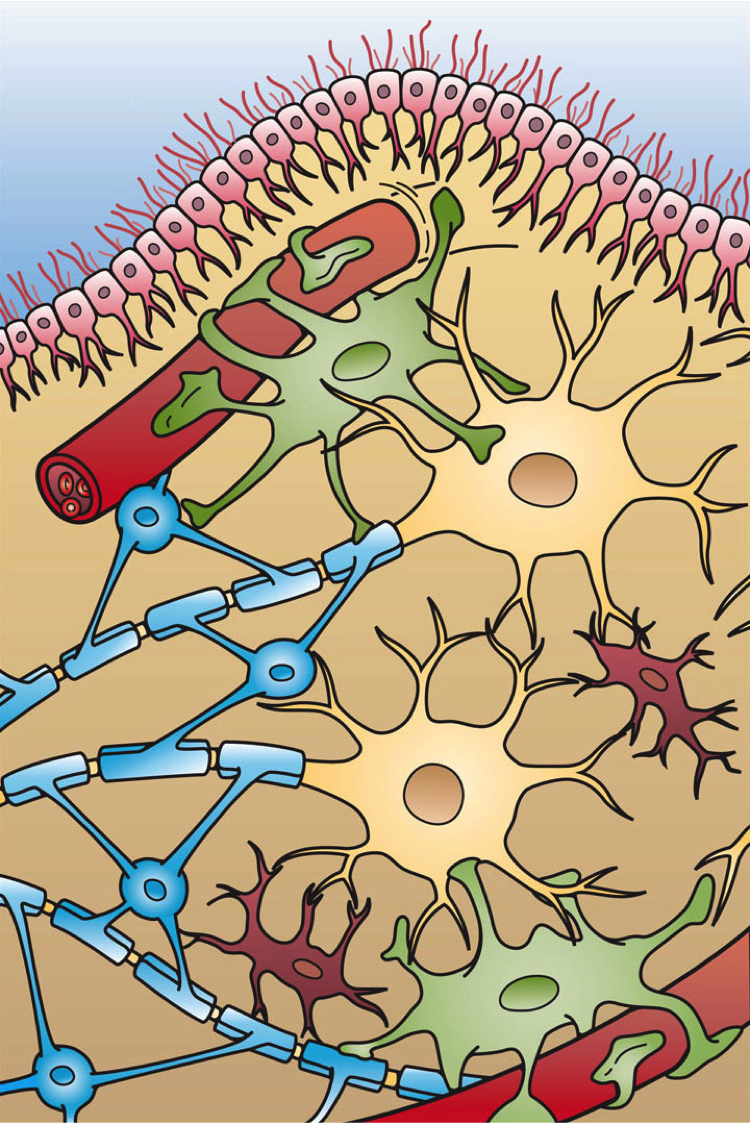

What about the role of our second brain…. the one with 200-600 million neurons that live in that middle part of our body (right next to / inside our pelvis)? Termed the enteric nervous system, this second brain both stores and produces neurotransmittersTurna, et.al., 2016, serves as the scaffolding of interplay between the ENS, SNS, and CNS. This ENS is home to the interface of “bugs, gut, and glial” which are “not only in anatomical proximity, but also influence and regulate each other…interconnected for mutual homeostasis.”Lerner, et.al., 2017 In fact, part of this process then directly impacts the brain. “Healthy brain function and modulation are dependent upon the microbiota’s [gut bugs] activity of the vagus nerve.”Turna, et.al., 2016. Further, “by direct routes or indirectly, through the gut mucosal system and its local immune system, microbial factors, cytokines, and gut hormones find their ways to the brain, thus impacting cognition, emotion, mood, stress resilience, recovery, appetite, metabolic balance, interoception and PAIN.”Lerner, et.al., 2017

What about the role of our second brain…. the one with 200-600 million neurons that live in that middle part of our body (right next to / inside our pelvis)? Termed the enteric nervous system, this second brain both stores and produces neurotransmittersTurna, et.al., 2016, serves as the scaffolding of interplay between the ENS, SNS, and CNS. This ENS is home to the interface of “bugs, gut, and glial” which are “not only in anatomical proximity, but also influence and regulate each other…interconnected for mutual homeostasis.”Lerner, et.al., 2017 In fact, part of this process then directly impacts the brain. “Healthy brain function and modulation are dependent upon the microbiota’s [gut bugs] activity of the vagus nerve.”Turna, et.al., 2016. Further, “by direct routes or indirectly, through the gut mucosal system and its local immune system, microbial factors, cytokines, and gut hormones find their ways to the brain, thus impacting cognition, emotion, mood, stress resilience, recovery, appetite, metabolic balance, interoception and PAIN.”Lerner, et.al., 2017

So, by process of logic, it requires little convincing to conclude that the food we eat or fail to eat directly impacts the health or dysfunction of this magnificently orchestrated system. One that directly and profoundly impacts our brain, our body, our being. And it’s a concept that our patients, our clients, ourselves, know in our gut to be true.

And it’s thanks to all the hard work of those who have come before us that we can share in the advancing understanding for the benefit of thousands who need your help, expertise and guidance. Please join me for Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist. The next course will be in Springfield, MO on June 23-24, 2018. Vital and clarifying information awaits you!

Live Active. (2013, Jan) Understanding Pain in less than 5 minutes, and what to do about it! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_3phB93rvI Retrieved March 28, 2018.

Lerner, A., Neidhofer, S., & Matthias, T. (2017). The Gut Microbiome Feelings of the Brain: A Perspective for Non-Microbiologists. Microorganisms, 5(4). doi:10.3390/microorganisms5040066

Turna, J., Grosman Kaplan, K., Anglin, R., & Van Ameringen, M. (2016). "What's Bugging the Gut in Ocd?" a Review of the Gut Microbiome in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Depress Anxiety, 33(3), 171-178. doi:10.1002/da.22454

There has been a bit of buzz on the various news outlets and social media feeds about the “new organ” the interstitium. On March 27th an article appeared in Scientific Reports, an online peer-reviewed journal from the publishers of Nature. This work was presented by a team of researchers that utilized a new in vivo laser endomicroscopy technique that demonstrated this tissue is a matrix of collagen bundles and elastic fibers surrounded by fluid rather than the tightly packed layers of connective tissue that was previously observed on fixed slides . This submucosal layer was observed in the entire gastrointestinal tract, the urinary bladder, bronchus, dermis, bronchus and peri-arterial soft tissue and fascia. The authors state, “In sum, we describe the anatomy and histology of a previously unrecognized, though widespread, macroscopic, fluid-filled space within and between tissues, a novel expansion and specification of the concept of the human interstitium” Benias et al., 2018.

The only thing ‘new’ is the way that this group of scientists observed the tissue that until now has primarily been studied ex vivo. I find it rather humorous to note that it is mainstream news that histologists in the 21st century just realized that there is a difference in the architecture of living versus dead tissue. They noted a significant change in the appearance of tissue slides that were chemically fixed in the traditional manner when compared to studies of in vivo structures as well as fresh frozen samples. The researchers noted this tissue in the dermis as well as urinary system, gastrointestinal system and respiratory system. This further supports one of my favorite talking points presented in the visceral mobilization courses “fascia is fascia is fascia is fascia.”

The only thing ‘new’ is the way that this group of scientists observed the tissue that until now has primarily been studied ex vivo. I find it rather humorous to note that it is mainstream news that histologists in the 21st century just realized that there is a difference in the architecture of living versus dead tissue. They noted a significant change in the appearance of tissue slides that were chemically fixed in the traditional manner when compared to studies of in vivo structures as well as fresh frozen samples. The researchers noted this tissue in the dermis as well as urinary system, gastrointestinal system and respiratory system. This further supports one of my favorite talking points presented in the visceral mobilization courses “fascia is fascia is fascia is fascia.”

As an instructor that presents entire courses around the importance of the fascial system within all structures of the body including the dermis, epimysium, all organs, and the adventitia of vessels, I am thrilled to see this layer of the fascial system receive recognition and garner the attention it deserves. However, to refer to the interstitium as a new undiscovered organ is to ignore the work of the International Fascia Research Congress as well as many other notable scientists. These researchers see the fascial system as the dynamic mesenchymal tissue that unites every cell in the body and allows for fluid and tissue movement.

French hand surgeon Dr. Jean-Claude Guimrberteau has documented this tissue utilizing microendoscopy on living subjects for the past 20 years. Dr Guimberteau created a brilliant DVD called Strolling Under the Skin, you can view an excerpt available on YouTube. Following the success of several videos, he went on to co-author the book Architecture of Human Living Fascia: The extracellular matrix and cells revealed through endoscopy.

Another brilliant researcher is Orthopedic Surgeon Dr. Carla Stecco. Her paper The Fascia: the forgotten structure is an excellent review of the three-dimensional continuity of the myofascia. Following multiple publications, she also authored the book The Functional Atlas of the Human Fascial System. Her work is limited to the myofascial layer and does not include the visceral fascia although she notes its presence in her published works. For those that would like to know more about this tissue, I highly recommend both of these authors. If you wish to explore how a physical therapist can utilize this information in clinical practice, join me for one of my courses on fascial manipulation. The fascial based treatment for pelvic dysfunction series includes:

- Mobilization of the Myofascial Layer: Pelvis and Lower Extremity

- Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Gastrointestinal System

- Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Reproductive System of Men and Women

Benias, P. C., Wells, R. G., Sackey-Aboagye, B., Klavan, H., Reidy, J., Buonocore, D., ... & Theise, N. D. (2018). Structure and Distribution of an Unrecognized Interstitium in Human Tissues. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 4947. https://:doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23062-6, 2018.

Stecco, C., Macchi, V., Porzionato, A., Duparc, F., & De Caro, R. (2011). The fascia: the forgotten structure. Italian journal of anatomy and embryology, 116(3), 127.

Sagira Vora, PT, MPT, WCS, PRPC practices in Bellevue, WA at the Overlake Hospital Medical Center, and she played a pivotal role in creating the Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification examination. Today's post is part one of a multi-part series on pelvic rehabilitation and sexual health. Stay tuned for part two!

“Have mind-blowing sex: learn how to do your Kegels.” “Amazing orgasms, ladies do your Kegels!” These were just some of the headlines that greeted me as I researched what was being said in the popular media regarding pelvic floor exercises and improving sexual function in women. Some other wisdom from popular women’s magazines included advice on, “stopping the flow of urine,” to do your Kegels. We know how much we pelvic floor therapists love hearing that phrase!

I found a few recent and past studies that have tried to study pelvic floor exercises and sexual function in women.

In 1984, Chambless et.al. studied a small group of women who were able to achieve orgasm through intercourse less than 30% of time. Strength gains in the pubococcygeus muscles were noted in the exercise group but neither the exercise nor control group achieved increased orgasmic frequency.

In a more recent study, Lara et. al. studied 32 sexually active post-menopausal women, who had the ability to contract their pelvic floor muscles, tested the hypothesis that 3 months of physical exercises including pelvic floor muscle training with biweekly physical therapy visits and exercise performed at home three times a week, would enhance sexual function. Pelvic floor muscle strength was significantly improved post-test, but this study found no effect on sexual function.

Forty years after Dr. Kegel’s assertion about sexual arousal enhancing properties of pubococcygeus muscle exercises, Messe and Geer tested Kegel’s hypothesis in their psychophysiological study, in which they asked women to perform vaginal contractions while engaging in sexual fantasy. A second group was asked to engage in sexual fantasy without the contractions, and yet a third group was given the task of vaginal contractions but no sexual fantasy. The results indicated that performing vaginal contractions with sexual fantasy improved arousal and orgasmic ability. Initially, this group made better gains than vaginal contractions alone and fantasizing alone. However, with a second test session one week later, no further gains were noted in the ability of this group to improve sexual arousal or orgasm. Messe and Geer speculated that increased muscle tone may result in increased stimulation of stretch and pressure receptors during intercourse, leading to enhanced arousal and orgasmic potential.

The most interesting finding was reported by an older study done by Roughan, who reported no differences in the groups he studied. Roughan et. al. expected women with orgasm difficulties to improve after 12-week period of pelvic floor strengthening exercises, compared to a group that practiced relaxation and an attention control group. No difference was found between the orgasmic ability of the two groups.

The majority of women studied here had no reported pelvic floor dysfunction. Perhaps, contrary to popular opinion and against the advice of women’s magazines, women with healthy pelvic floors may not benefit from pelvic floor exercises any more than they would from relaxation training, or mindful attention to sexual stimuli.

So, what then, will increase our mojo in bed, you ask? Stay tuned for the next blogs…

Chambless D, Sultan FE, Stern TE, O’Neill C, Garrison S. Jackson A. Effect of pubococcygeal exercise on coital orgasm in women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984; 52:114-8

Laan E. Rellini AH. Can we treat anorgasmia in women? The challenge to experiencing pleasure: Sex Relation Ther. 2011:26:329-41

Messe MR, Geer JH. Voluntary vaginal musculature contractions as an enhancer of sexual arousal. Arch Sex Behav. 1985; 14:13-28

Padoa, Anna. Rosenbaum, Talli. 1st edition. 2016. The Overactive Pelvic Floor.

Roughan PA, Kunst L. Do pelvic floor exercises really improve orgasmic potential? J Sex Marital Ther. 1984;7:223-9